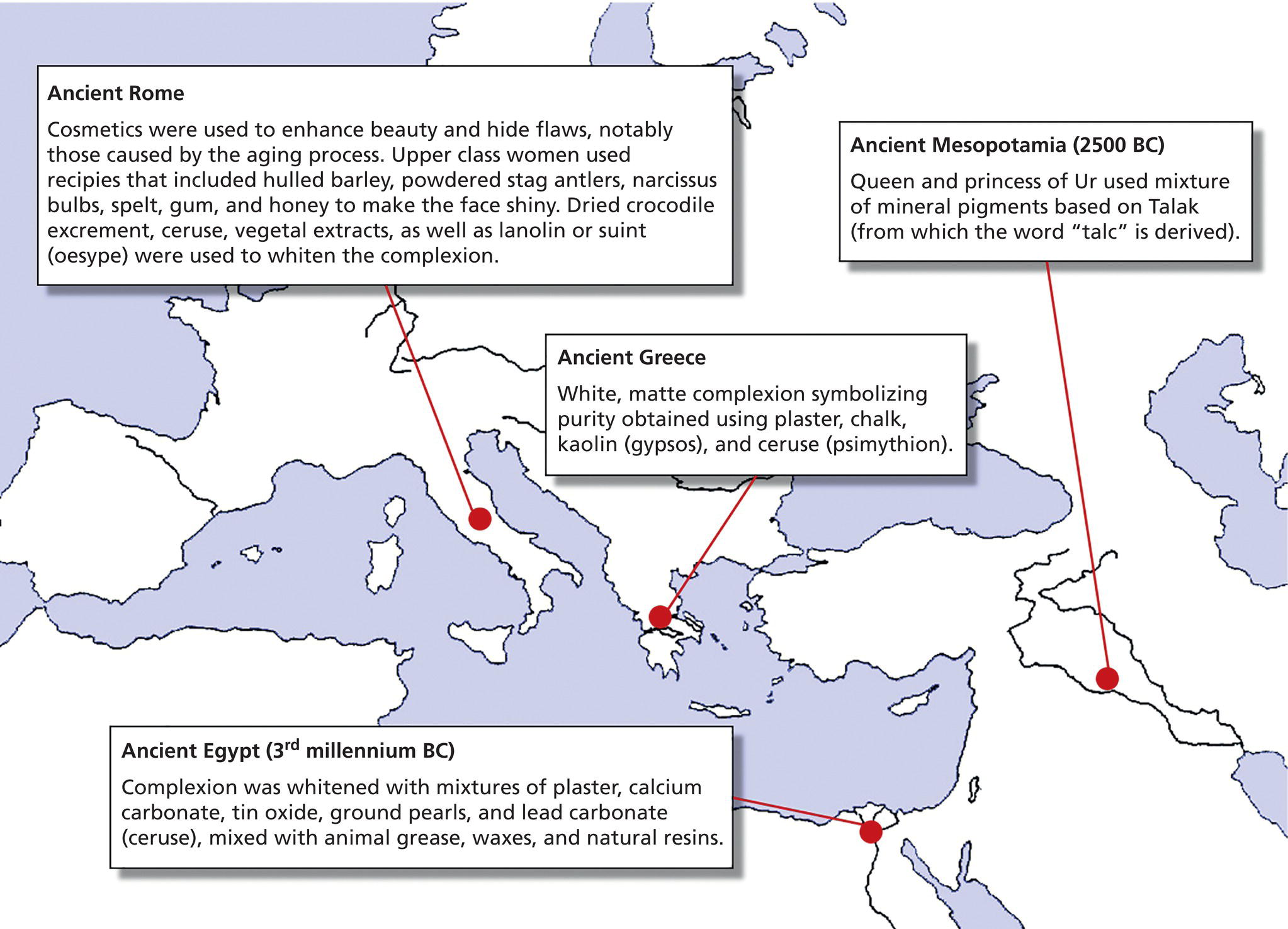

Sylvie Guichard1, Véronique Roulier1, Brian Bodnar2, and Audrey Ricard2 1 L’Oréal Research, Chevilly‐Larue, France 2 L’Oréal Research and Innovation, Clark, NJ, USA Complexion makeup is complicated, nontrivial, and deeply rooted in human history. It has evolved along with civilizations, fashions, scientific knowledge, and technologies to meet user expectations depending on mood, nature, culture, and skin color. A prime stage to beautifying the face, complexion makeup creates the “canvas” on which coloring materials are placed. Women consider it as a tool to even skin tone, modify skin color, or contribute to smoothing out the skin surface. In order to satisfy these different objectives, substances extracted from nature took on various forms over time until formulation experts developed a complex category of cosmetics including emulsions, poured compacts, and both compact and loose powders. These developments have improved the field of skin care providing radiance, wear, and sensory effects. It remains a challenge to adequately satisfy the varying makeup requirements of women from different ethnic origins, who do not apply products in the same way and do not share the same diverse canons of beauty. It is, therefore, necessary to gain a thorough understanding of the world’s representative diversity of skin tones. Finally, as a product intended to be in intimate contact with the skin, facial foundations must meet the most strenuous demands of quality and safety. This has motivated evaluation teams to develop methods for assessing product performance. Modifying one’s self‐appearance by adding color and ornament to the skin of the face and body skin is hardly a recent trend [1–3]. From Paleolithic times, man has decorated himself with body paint and tattoos for various ritual activities. In the Niaux Cavern (Ariège, France), the cave of Cougnac (Lot, France), and the Magdalenian Galleries of le Mas d’Azil (Ariège), the past ages have left evidence of these practices. Along with flint tools in the Magdalenian Galleries at le Mas d’Azil, ochre nodules were found that look like “sticks of makeup” as well as grinding instruments, jars, spatulas, and needle‐like “rods” 8–11 cm long, tapered at one end and spatula‐shaped on the other end, suitable for applying body paint. From the earliest of ancient civilizations, there are cosmetic recipes containing a variety of ingredients which are often closer to magic than to rational chemistry, aimed particularly at modifying the complexion. Usually used exclusively by high dignitaries, cosmetics were intended mostly to whiten the complexion, where a variety of techniques and methods were used (Figure 24.1). Some ancient cosmetic recipes were quite complex and can be determined through chemical analyses, such as those carried out jointly by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, L’Oréal’s Recherche department, the Research Laboratory of the Museums of France, and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility on the content of cosmetic flasks found in archeologic excavations [4]. The earliest cosmetic formulary is attributed to Cleopatra – “Cleopatrae gyneciarum libri.” In addition, an analysis was made of an ointment can, christened Londinium, discovered in London when excavating a temple dated at the middle of the 2nd century AD. It contained glucose‐based polymers, starch, and tin oxide. The white appearance of the cream reflects a certain level of technological refinement [5]. Figure 24.1 Usage of complexion cosmetics in the ancient world. In Europe, from the Middle Ages up to the middle of the twentieth century, some makeup was based on water, roses, and flour; however, use of lead carbonate (ceruse), mixed with arsenic and mercury sublimates were being used during the Renaissance to give the complexion a fine silver hue. Understandably, the toxic effects of these cosmetics were beginning to worry the authorities. In 1779, following the onset of a number of serious cases, the manufacture of “foundation bases” was placed under the control of the Société Royale de Médicine, which had just been set up in 1778. The toxic components were then removed. This measure seems to have made them disappear from the market, but it was not until 1915 that the use of ceruse was officially prohibited. In 1873, Ludwig Leichner, a singer at the Berlin Opera, sought a way to preserve his skin tone by creating his own foundation base from natural pigments. In 1883, Alexandre Napoléon Bourjois devised the first dry or pastel foundation. Bourjois was about to launch his first dry blush, Pastel Joue. With the birth of the cosmetics industry, products were widely distributed. Modern manufacturing techniques with production on an industrial scale coupled with the beginning of mass consumer use started at the beginning of the twentieth century. In the twentieth century, fashionable powders for the complexion became more sophisticated [6, 7]. Market choice extended with the launch of new brands such as Gemey, Caron, and Elizabeth Arden. The 1930s saw the development of trademarks such as Helena Rubinstein and Max Factor created by professional movie and Hollywood makeup artists. The products were suited to the requirements of the movie studios. Extremely opaque, tinted with gaudy colors, they were compact and difficult to apply. After the success of Max Factor’s Pancake and Panstick cosmetics, use of the word “makeup” became widespread. Initiated by Chanel in 1936, the fashion in Europe and the USA began to switch from white to a tanned complexion. Even though women were more inclined to wear cosmetics, makeup was still not part of everyday life. Pancake makeup, a mixture of stearate, lanolin, and dry powders, was not easy to apply. Technical advances gradually made products more practical. The box of loose powder was equipped with a sieve in 1937 (Caron). In 1940, Lancôme launched Discoteint, a creamy version of its compact. Coty micronized its powder (Air Spun) in 1948. Yet, it was not until the 1950s that a real boom occurred in the number of products on the market. Compact makeup was made available in creamy form; foundation became a fluid cream (Gemey, Teint Clair Fluide, 1954). It was the start of a great diversification of formulations: fluids, dry or creamy compacts, sticks, and powders. Makeup became multifaceted, with more sophisticated effects, including moisturizing, protection from damaging environmental factors, and other skincare properties in addition to providing color. Since then, complexion makeup has followed the continuous changes in regulations and advances in biologic knowledge, especially in the area of skin physiology. Over the last decades, it has benefitted from technologic progress in the field of raw materials, as well as from enhanced understanding and gains in optics and physical chemistry. Finally, makeup was enriched with the diversity of cultures from all over the world prompted by globalization. The beginning of the twenty‐first century opens a new era of visual effects, sensory factors, and multiculturalism. Women expect foundations to effect a veritable transformation that hides surface imperfections, blemishes, discolorations, and wrinkles, while enhancing a dull complexion and making shiny skin more satiny. Whereas making up the eyes and the lips is generally done playfully, the complexion receives more attention. It is in this area that women display their greatest expertise and are the most demanding. Women have high expectations for their foundation including: In order to satisfy diverse demands, a large number of products types and forms have been developed, including fluid foundations, compacts, and powders (Figure 24.2). In order to achieve the variety of textures, modern formulations use a variety of different ingredients – each serving a specific purpose within the final product (Table 24.1). Fluid foundations include both oil‐in‐water (O/W) and water‐in‐oil (W/O) emulsions. The advantages of emulsion formulations, in general, relates to their extreme versatility: fluid vs. solid, able to accommodate both oil‐ and water‐phase ingredients, and having unique and tunable esthetics. Early foundation formulas were O/W emulsions; however, in the 1990s, the first W/O formulations revolutionized the foundation market. The main benefits of the W/O formulations over O/W formulas include textures with longer drying times and longer lastingness. In addition, many fillers and other ingredients are easily added to the external oil phase, yielding huge improvements in overall esthetics. Figure 24.2 Diversity of textures: from fluid emulsion to paste dispersion. Table 24.1 Typical ingredients found within complexion makeup formulations.

CHAPTER 24

Facial Foundation

Introduction

Complexion makeup – an ancient practice

From the middle ages to the nineteenth century

Twentieth century: the industrial era and diversification

Formulation diversity

Formulations: anatomy of foundations

Emulsion foundations

Ingredient type

Examples

Purpose

Pigments

Iron oxides, titanium dioxide

Imparting color to the product and skin

Fillers

Talc, mica, kaolin, polymeric, or silicone fillers

Esthetics on skin; ease of application; oil control; optical effects; lastingness; thickening/texture

Emulsifiers

PEG‐10 dimethicone, cetyl/PEG/PPG‐10/1 dimethicone, polyglyceryl‐4 isostearate

Allow oils (silicone or hydrocarbons) and water phases to mix and form an emulsion ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access