Cutaneous Manifestations of Other Leukemias

Besides B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) and myelogenous leukemias, the skin may be the site of specific manifestations in other types of leukemia. In most cases the leukemia is already known and cutaneous lesions are not biopsied, as the diagnosis is already established. There are no exact data on frequency of skin involvement by different types of leukemia, but B-CLL and myelogenous leukemia (covered in Chapters 19 and 20, respectively) represent by far the most frequent types.

Most cases of skin involvement by different types of leukemia present with papules, plaques, and nodules that retain, at least in part, the histopathologic and phenotypic features of the original disease. Some leukemias described in the following paragraphs present with peculiar manifestations that pose problems in the differential diagnosis and are worth a brief description.

Interestingly, similar to what may be observed in B-CLL and myelogenous leukemias, in other types of leukemia, too, specific skin manifestations have been observed at sites of cutaneous inflammation, suggesting that this mechanism of skin infiltration is common to several types of leukemia, irrespective of the specific classification [1]. In this context, I have observed patients with Sézary syndrome or with late leukemic manifestations of mycosis fungoides who developed specific skin manifestations at the site of drug eruptions, conceptually similar to leukemic infiltrates at sites of skin inflammation.

T-Cell Prolymphocytic Leukemia

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) is a rare hematologic disease [2]. Cutaneous involvement occurs in up to one-third of patients and is characterized by papules, plaques, or tumors often indistinguishable from those of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome. Erythroderma may develop (Fig. 22.1). Skin manifestations may be the first sign of the disease [3, 4].

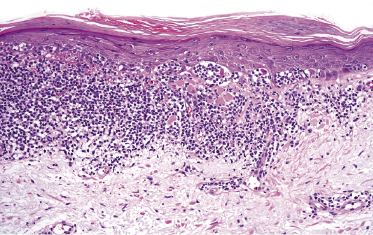

Histology reveals a monomorphous infiltrate of small lymphocytes, sometimes with epidermotropism (Fig. 22.2). Immunohistology shows an α/β T-helper phenotype (βF1+, CD2+, CD3+, CD4+, CD7+, CD8−) in the majority of lesions, but co-expression of CD4 and CD8 is found in about one-quarter of cases. CD52 is strongly expressed. Markers of T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (TdT, CD1a) are negative.

The T-cell receptor (TCR) genes are monoclonally rearranged. The most frequent chromosomal aberrations are inversion of chromosome 14 with breakpoints in the long arm at q11 (TCR alpha/delta), q32 (TCL1 gene), or Xq28 (MTCP-1 gene), abnormalities of chromosome 8, and deletions of the long arm of chromosomes 5, 6, 11, and 13 [2].

The disease usually runs an aggressive course and prognosis is poor. Anti-CD52 antibody (alemtuzumab) is the treatment of choice [5]. The rationale for the treatment is provided by the strong CD52 positivity of neoplastic cells. Consolidation of remissions with autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation is used to prolongue survival, offering a potential chance for cure.

It is interesting to note that a report described a patient with a previous “lymphomatoid contact dermatitis” who during follow-up developed a T-PLL, once more showing the difficulties in diagnosis and differential diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoproliferative diseases [6].

Differentiation of cutaneous manifestations of T-PLL from Sézary syndrome may be extremely difficult on clinicopathologic grounds alone. In contrast to T-PLL, the bone marrow is usually not involved in Sézary syndrome.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree