The Skin in Immune, Autoimmune, and Rheumatic Disorders

Epidemiology and Etiology

Incidence. 15-23% of the population may have had this condition during their lifetime.

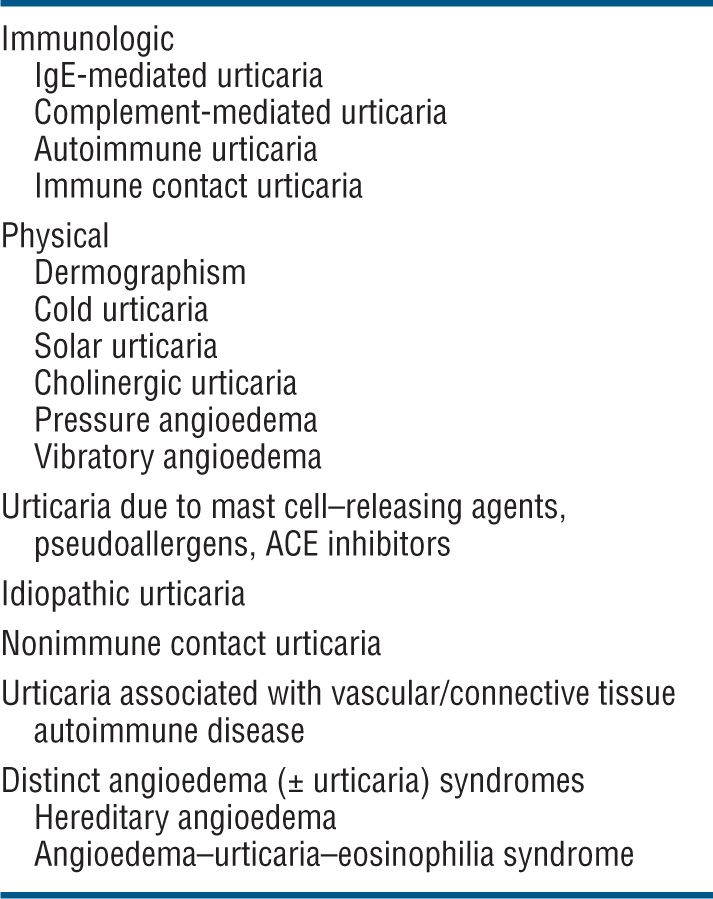

Etiology. Urticaria/angioedema is not a disease but a cutaneous reaction pattern. For classification and etiology, see Table 14-1.

Table 14-1 ETIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION OF URTICARIA/ANGIOEDEMA

Clinical Types

Acute Urticaria. Acute onset and recurring over <30 days. Usually large wheals often associated with angioedema (Figs. 14-6 and 14-7); often IgE dependent with atopic diathesis; related to foods, parasites, and penicillin. Also, complement mediated in serum sickness-like reactions (whole blood, immunoglobulins, penicillin). Often accompanied by angioedema. Common. (See also “Drug-Induced Acute Urticaria” in Section 23.)

Chronic Urticaria. Recurring over <30 days. Small and large wheals (Fig. 14-8). Rarely IgE dependent but often due to anti-FcεR auto-antibodies; etiology unknown in 80% and therefore considered idiopathic. Intolerance to salicylates, benzoates. Common. Chronic urticaria affects adults predominantly and is approximately twice as common in women as in men. Up to 40% of patients with chronic urticaria of >6 months’ duration still have urticaria 10 years later.

Symptoms. Pruritus. In angioedema of palms and soles pain. Angioedema of tongue, pharynx interferes with speech, food intake, and breathing. Angioedema of larynx may lead to asphyxia.

Clinical Manifestation

Skin Lesions. Sharply defined wheals (Fig. 14-6), small (<1 cm) to large (>8 cm), erythematous or white with an erythematous rim, round, oval, acriform, annular, serpiginous (Figs. 14-6 and 14-8), due to confluence and resolution in one area and progression in another (Fig. 14-8). Lesions are pruritic and transient.

Angioedema—skin colored, transient enlargement of portion of face (eyelids, lips, tongue) (Figs. 14-7 and 23-5), extremity, or other sites due to subcutaneous edema.

Distribution. Usually regional or generalized. Localized in solar, pressure, vibration, and cold urticaria/angioedema and confined to the site of the trigger mechanism (see below).

Special Features/As Related to Pathogenesis

Immunologic Urticaria. IgE Mediated. Lesions in acute IgE-mediated urticaria result from antigen-induced release of biologically active molecules from mast cells or basophilic leukocytes sensitized with specific IgE antibodies (type I anaphylactic hypersensitivity). Released mediators increase venular permeability and modulate the release of biologically active molecules from other cell types. Often with atopic background. Antigens: food (milk, eggs, wheat, shellfish, nuts), therapeutic agents, drugs (penicillin) (see also “Drug-Induced Acute Urticaria, Angioedema, Edema, and Anaphylaxis” in Section 23), helminths. Most often acute (Figs. 14-6 and 23-5).

Complement Mediated. Acute. By way of immune complexes activating complement and releasing anaphylatoxins that induce mast cell degranulation. Serum sickness, administration of whole blood, immunoglobulins. Autoimmune. Common, chronic. Autoantibodies against FcεRI and/or IgE. Positive autologous serum skin test. Clinically, patients with these autoantibodies (up to 40% of patients with chronic urticaria) are indistinguishable from those without them (Fig. 14-8). These autoantibodies may explain why plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, and cyclosporine induce remission of disease activity in these patients.

Immunologic Contact Urticaria. Usually in children with atopic dermatitis sensitized to environmental allergens (grass, animals) or individuals sensitized to wearing latex rubber gloves; can be accompanied by anaphylaxis.

Physical Urticarias. Dermographism. Linear urticarial lesions occur after stroking or scratching the skin; they itch and fade in 30 min (Fig. 14-9); 4.2% of the normal population have it; symptomatic dermographism is a nuisance.

Figure 14-9. Urticaria: dermographism Urticaria as it appeared 5 min after the patient was scratched on the back. The patient had experienced generalized pruritus for several months with no spontaneously occurring urticaria.

Cold Urticaria. Usually in children or young adults; urticarial lesions confined to sites exposed to cold occurring within minutes after rewarming. “Ice cube” test (application of an ice cube for a few minutes to skin) causes wheal.

Solar Urticaria. Urticaria after solar exposure. Action spectrum from 290 to 500 nm; whealing lasts for <1 h, may be accompanied by syncope; histamine is one of the mediators (see Section 10 and Fig. 10-11).

Cholinergic Urticaria. Exercise to the point of sweating provokes typical small, papular, highly pruritic urticarial lesions (Fig. 14-10). May be accompanied by wheezing.

Figure 14-10. Cholinergic urticaria Small urticarial papules on neck occurring within 30 min of vigorous exercise. Papular urticarial lesions are best seen under side lighting.

Aquagenic Urticaria. Very rare. Contact with water of any temperature induces eruption similar to cholinergic urticaria.

Pressure Angioedema. Erythematous swelling induced by sustained pressure (buttock swelling when seated, hand swelling after hammering, foot swelling after walking). Delayed (30 min to 12 h). Painful, may persist for several days, and interferes with quality of life. No laboratory abnormalities; fever may occur.

Vibration Angioedema. May be familial (autosomal dominant) or sporadic. Rare. It is believed to result from histamine release from mast cells caused by a “vibrating” stimulus—rubbing a towel across the back produces lesions, but direct pressure (without movements) does not.

Urticaria Due to Mast Cell-Releasing Agents and Pseudoallergens and Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria. Urticaria/angioedema and even anaphylaxis-like symptoms may occur with radiocontrast media and as a consequence of intolerance to salicylates, food preservatives and additives (e.g., benzoic acid and sodium benzoate), several azo dyes, including tartrazine and sunset yellow (pseudoallergens) (Fig. 14-8); also to ACE inhibitors. May be acute and chronic. In chronic idiopathic urticaria, histamine derived from mast cells in the skin is considered the major mediator, also eicosanoids and neuropeptides.

Nonimmune Contact Urticaria. Due to direct effects of exogenous urticants penetrating into skin or blood vessels. Localized to site of contact. Sorbic acid, benzoic acid in eye solutions and foods, cinnamic aldehydes in cosmetics, histamine, acetylcholine, serotonin in nettle stings.

Urticaria Associated with Vascular/Connective Tissue Autoimmune Disease. Urticarial lesions may be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and Sjögren syndrome. However, in most instances, they represent urticarial vasculitis (see p. 363).

Distinct Angioedema (± Urticaria) Syndromes. Hereditary Angioedema (HAE). A serious autosomal-dominant disorder; may follow trauma (physical and emotional). Angioedema of the face (Fig. 14-11) and extremities, episodes of laryngeal edema, and acute abdominal pain caused by angioedema of the bowel wall presenting as surgical emergency. Urticaria rarely occurs. Laboratory abnormalities involve the complement system: decreased levels of C1-esterase inhibitor (85%) or dysfunctional inhibitor (15%), low C4 value in the presence of normal C1 and C3 levels. Angioedema results from bradykinin formation, since C1-esterase inhibitor is also the major inhibitor of the Hageman factor and kallikrein, the two enzymes required for kinin formation. Episodes can be life threatening.

Figure 14-11. Hereditary angioedema (A) Severe edema of the face during an episode leading to grotesque disfigurement. (B) Angioedema will subside within hours. These are the normal features of the patient. The patient had a positive family history and had multiple similar episodes including colicky abdominal pain.

Angioedema-Urticaria-Eosinophilia Syndrome. Severe angioedema, only occasionally with pruritic urticaria, involving the face, neck, extremities, and trunk that lasts for 7–10 days. There is fever and marked increase in normal weight (increased by 10–18%) owing to fluid retention. No other organs are involved. Laboratory abnormalities include striking leukocytosis (20,000–70,000/μL) and eosinophilia (60–80% eosinophils), which are related to the severity of attack. There is no family history. This condition is rare, prognosis is good.

Laboratory Examinations

Serology. Search for hepatitis B–associated antigen, assessment of the complement system, assessment of specific IgE antibodies by radioallergosorbent test (RAST), anti-FcεRI autoantibodies. Serology for lupus and Sjögren syndrome. Autologous serum skin test for autoimmune urticaria.

Hematology. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is often elevated in urticarial vasculitis, and there may be hypocomplementemia; transient eosinophilia in urticaria from reactions to foods, parasites, and drugs; high levels of eosinophilia in the angioedema–urticaria–eosinophilia syndrome.

Complement Studies. Screening for functional C1 inhibitor in HAE.

Ultrasonography. For early diagnosis of bowel involvement in HAE; if abdominal pain is present, this may indicate edema of the bowel.

Parasitology. Stool specimen for presence of parasites.

Diagnosis

A detailed history (previous diseases, drugs, foods, parasites, physical exertion, solar exposure) is of utmost importance. History should differentiate between type of lesions—urticaria, angioedema, or urticaria + angioedema; duration of lesions (<1 h or ≥1 h), pruritus; pain on walking (in foot involvement), flushing, burning, and wheezing (in cholinergic urticaria). Fever in serum sickness and in the angioedema–urticaria–eosinophilia syndrome; in angioedema, hoarseness, stridor, dyspnea. Arthralgia (serum sickness, urticarial vasculitis), abdominal colicky pain in HAE. A careful history of medications including penicillin, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and ACE inhibitors should be obtained.

Dermographism is evoked by stroking the skin; pressure urticaria is tested by application of pressure (weight) perpendicular to the skin; vibration angioedema by a vibratory stimulus, like rubbing the back with a towel. Cholinergic urticaria can best be diagnosed by exercise to sweating and intracutaneous injection of acetylcholine or mecholyl, which will produce micropapular whealing. Solar urticaria is verified by testing with UVB, UVA, and visible light (see Fig. 10-11). Cold urticaria is verified by a wheal response to the application to the skin of an ice cube or a test tube containing ice water. Autoimmune urticaria is tested by the autologous serum skin test and determination of anti-FcεRI antibody. If urticarial wheals do not disappear in ≤24 h, urticarial vasculitis should be suspected and a biopsy done. The person with angioedema–urticaria–eosinophilia syndrome has high fever, high leukocytosis (mostly eosinophils), a striking increase in body weight due to retention of water, and a cyclic pattern that may occur and recur over a period of years. HAE has a positive family history and is characterized by angioedema as the result of trauma, abdominal pain, and decreased levels of C4 and C1-esterase inhibitor.

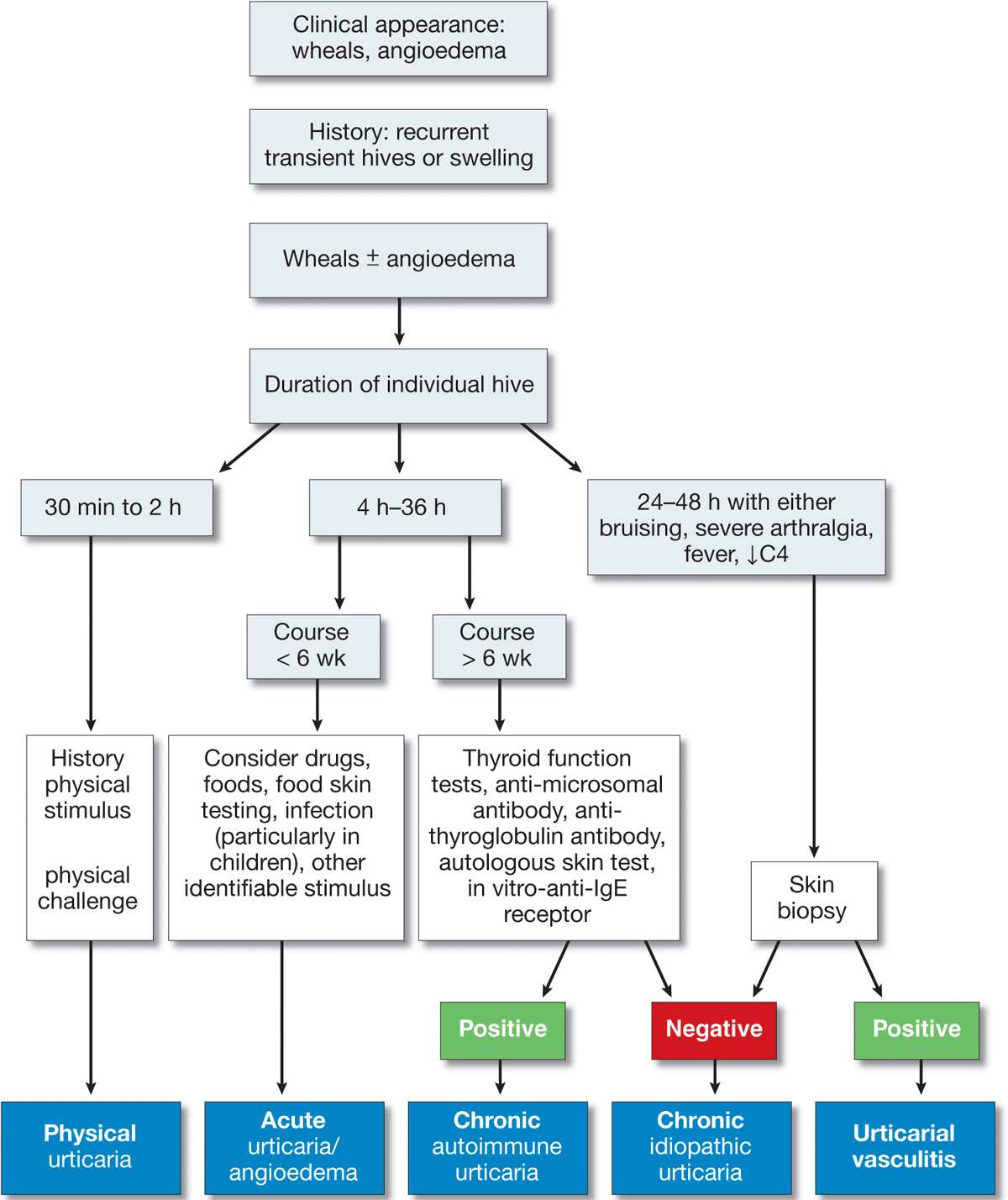

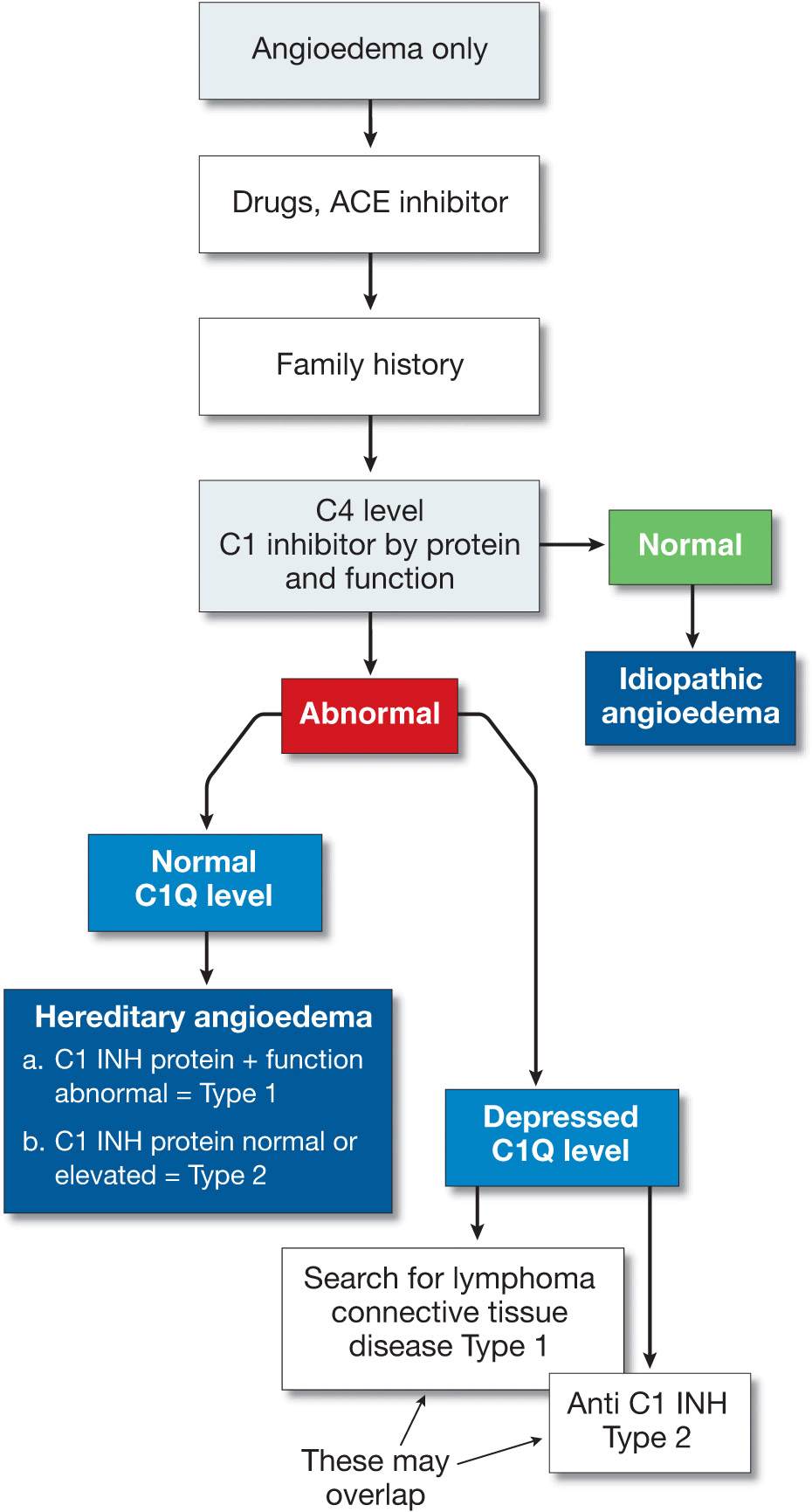

A practical approach to the diagnosis of urticaria/angioedema is shown in Fig. 14-12 and to angioedema alone in Fig. 14-13.

Figure 14-12. Approach to the patient with urticaria/angioedema. [Modified from Kaplan AP, in Wolff K et al. (eds.): Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 7th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2008:339.]

Figure 14-13. Approach to the patient with angioedema (without urticaria). [Modified from Kaplan AP in Wolff K et al. (eds.): Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 7th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2008:339.]

Course and Prognosis

Half of the patients with urticaria alone are free of lesions in 1 year, but 20% have lesions for >20 years. Prognosis is good in most syndromes except HAE, which may be fatal if untreated.

Management

Prevention by elimination of etiologic chemicals or drugs: aspirin and food additives, especially in chronic recurrent urticaria—rarely successful; prevent trigger in physical urticarias.

Antihistamines. H1-blockers, e.g., hydroxyzine, terfenadine; or loratadine, cetirizine, fexofenadine; 180 mg/d of fexofenadine or 10–20 mg/d of loratadine usually controls most cases of chronic urticaria, but cessation of therapy usually results in a recurrence; if they fail, H1 and H2 blockers (cimetidine) and/or mast cell–stabilizing agents (ketotifen). Doxepin, a tricyclic antidepressant with marked H1 antihistaminic activity, is valuable when severe urticaria is associated with anxiety and depression.

Prednisone. In acute urticaria with angioedema; also for angioedema–urticaria–eosinophilia syndrome.

Danazol or Stanozolol. Long-term therapy for HAE; watch out for hirsutism, irregular menses; whole fresh plasma or C1-esterase inhibitor in the acute attack. A very effective bradikin-B2-receptor antagonist for subcutaneous application is now available in Europe (Icatibant).

Other. In chronic idiopathic or autoimmune urticaria, if no response to antihistamines: switch to cyclosporine and taper gradually, if glucocorticoids are contraindicated or if side effects occur.

Epidemiology

Age of Onset. 50% under 20 years.

Sex. More frequent in males than in females.

Etiology

A cutaneous reaction to a variety of antigenic stimuli, most commonly to herpes simplex.

Infection. Herpes simplex, Mycoplasma.

Drugs. Sulfonamides, phenytoin, barbiturates, phenylbutazone, penicillin, allopurinol.

Idiopathic. Probably also due to undetected herpes simplex or Mycoplasma.

Clinical Manifestation

Evolution of lesions over several days. May have history of prior EM. May be pruritic or painful, particularly mouth lesions. In severe forms constitutional symptoms such as fever, weakness, malaise.

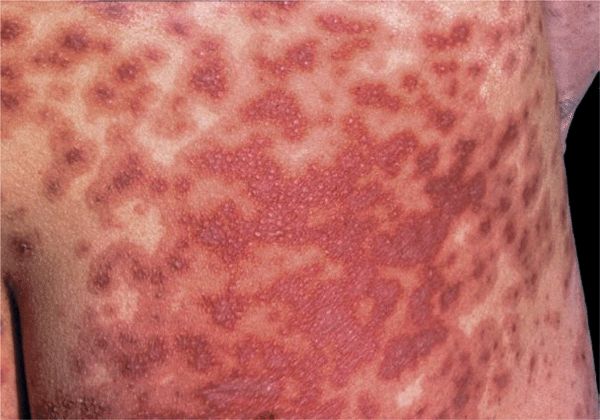

Skin Lesions. Lesions may develop over ≥10 days. Macule → papule (1–2 cm) → vesicles and bullae in the center of the papule. Dull red. Iris or target-like lesions result and are typical (Figs. 14-14 and 14-15). Localized to hands and face or generalized (Figs. 14-16 and 14-17). Bilateral and often symmetric.

Figure 14-14. Erythema multiforme Iris or target lesions on the palm of a 16-year-old. The lesions are very flat papules with a red rim, a violaceous ring, and a red center.

Figure 14-15. Erythema multiforme: minor Multiple, confluent, target-like papules on the face of a 12-year-old boy. The target morphology of the lesions is best seen on the lips.

Figure 14-16. Erythema multiforme: major Erythematous, confluent, target-like papules, erosions and crusts on the face. There is erosive and crusted cheilitis indicating mucosal involvement, and there is conjunctivitis. The patient also had a generalized rash consisting of iris lesions.

Figure 14-17. Erythema multiforme: major Multiple, target lesions have coalesced, and erosions will develop. This patient had fever and mucosal involvement of mouth, conjunctiva, and genitalia.

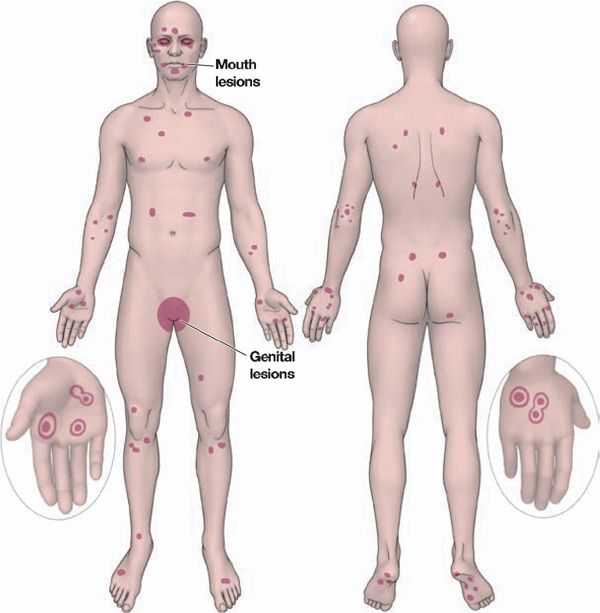

Sites of Predilection. Dorsa of hands, palms, and soles; forearms; feet; face; elbows and knees; penis (50%) and vulva (see Fig. 14-18).

Figure 14-18. Erythema multiforme predilection sites and distribution.

Mucous Membranes. Erosions with fibrin membranes; occasionally ulcerations: lips (Fig. 14-15, see also Section 33), oropharynx, nasal, conjunctival (Fig. 14-16), vulvar, anal.

Other Organs. Eyes, with corneal ulcers, anterior uveitis.

Course

Mild Forms (EM Minor). Little or no mucous membrane involvement; vesicles but no bullae or systemic symptoms. Eruption usually confined to extremities, face, classic target lesions (Figs. 14-14 and 14-15). Recurrent EM minor is usually associated with an outbreak of herpes simplex preceding it by several days.

Severe Forms (EM Major). Most often occurs as a drug reaction, always with mucous membrane involvement; severe, extensive, tendency to become confluent and bullous, positive Nikolsky sign in erythematous lesions (Figs. 14-16 and 14-17). Systemic symptoms: fever, prostration. Cheilitis and stomatitis interfere with eating; vulvitis and balanitis with micturition. Conjunctivitis can lead to keratitis and ulceration; lesions also in pharynx and larynx.

Laboratory Examination

Dermatopathology. Inflammation characterized by perivascular mononuclear infiltrate, edema of the upper dermis; apoptosis of keratinocytes with focal epidermal necrosis and subepidermal bulla formation. In severe cases, complete necrosis of epidermis as in toxic epidermal necrolysis. (See Section 8.)

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The target-like lesion and the symmetry are quite typical, and the diagnosis is not difficult.

Acute Exanthematic Eruptions. Drug eruption, psoriasis, secondary syphilis, urticaria, generalized Sweet syndrome. Mucous membrane lesions may present a difficult differential diagnosis: bullous diseases, fixed drug eruption, acute lupus erythematosus, primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.

Management

Prevention. Control of herpes simplex using oral valaciclovir or famciclovir may prevent development of recurrent EM.

Glucocorticoids. In severely ill patients, systemic glucocorticoids are usually given (prednisone, 50–80 mg/d in divided doses, quickly tapered), but their effectiveness has not been established by controlled studies.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Age of Onset. 30–60 years.

Sex. Females > males.

Etiology. Idiopathic in most cases but cell-mediated immunity plays a major role. Majority of lymphocytes in the infiltrate are CD8+ and CD45Ro+ (memory) cells. Drugs, metals (gold, mercury), or infection (hepatitis C virus) result in alteration in cell-mediated immunity. There could be HLA-associated genetic susceptibility that would explain a predisposition in certain persons. Lichenoid lesions of chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) of skin are indistinguishable from those of LP (see Section 22).

Clinical Manifestation

Onset. Acute (days) or insidious (over weeks). Lesions last months to years, asymptomatic or pruritic; sometimes severe pruritus. Mucous membrane lesions are painful, especially when ulcerated.

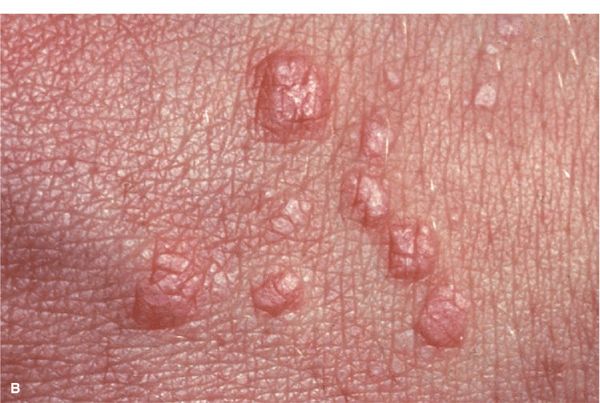

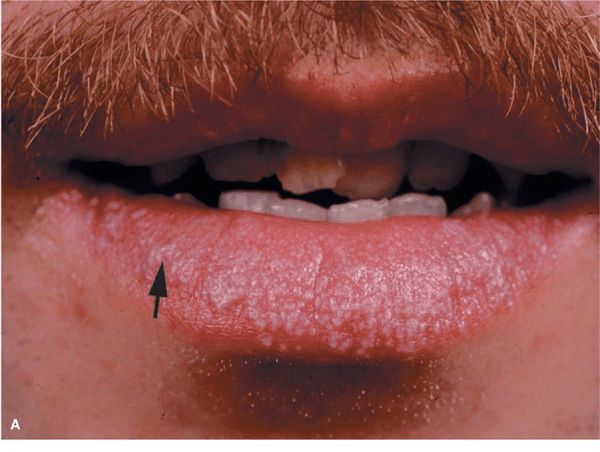

Skin Lesions. Papules, flat-topped, 1–10 mm, sharply defined, shiny (Fig. 14-20). Violaceous, with white lines (Wickham striae) (Fig. 14-20A), seen best with hand lens after application of mineral oil. Polygonal or oval (Fig. 14-20B). Grouped (Figs. 14-20 and 14-21), annular, or disseminated scattered discrete lesions when generalized (Fig. 14-22). In dark-skinned individuals, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is common. May present on lips (Fig. 14-23A) and in a linear arrangement after trauma (Koebner or isomorphic phenomenon (Fig. 14-23B).

Figure 14-20. Lichen planus (A) Flat-topped, polygonal, sharply defined papules of violaceous color, grouped and confluent. Surface is shiny and, upon close inspection with a hand lens, fine white lines are revealed (Wickham striae, arrow). (B) Close up of flat-topped shiny violaceous papules that are polygonal.

Figure 14-21. Hypertrophic lichen planus (A) Confluent hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on the dorsum of the hand of a light-colored man of African descent. Hyperkeratosis covers Wickham striae, and the characteristic violaceous color of the lesions can be seen only at the very margins. (B) Hypertrophic lichen planus on the dorsum of the foot. Lesions form thick plaques with a hyperkeratotic surface and a violaceous border.

Figure 14-22. Disseminated lichen planus A shower of disseminated papules on the trunk and the extremities (not shown) in a 45-year-old Filipino. Due to the ethnic color of the skin, the papules are not as violaceous as in Caucasians but have a brownish hue.

Figure 14-23. Lichen planus (A) Silvery-white, confluent, flat-topped papules on the lips. Note: Wickham striae (arrow). (B) Lichen planus, Koebner phenomenon. Linear arrangement of flat-topped, shiny papules that erupted after scratching.

Sites of Predilection. Wrists (flexor), lumbar region, shins (thicker, hyperkeratotic lesions; Fig. 14-21B), scalp, glans penis (see Section 36), mouth (see Section 35).

Variants

Hypertrophic. Large thick plaques arise on the foot (Fig. 14-21B), dorsum of hands (Fig. 14-21A), and shins; more common in black males. Although typical LP papule is smooth, hypertrophic lesions may become hyperkeratotic.

Atrophic. White-bluish, well-demarcated papules and plaques with central atrophy.

Follicular. Individual keratotic-follicular papules and plaques that lead to cicatricial alopecia. Spinous follicular lesions, typical skin and mucous membrane LP, and cicatricial alopecia of the scalp are called Graham Little syndrome (see Section 33).

Vesicular. Vesicular or bullous lesions may develop within LP patches or independent of them within normal-appearing skin. There are direct immunofluorescence findings consistent with bullous pemphigoid, and the sera of these patients contain bullous pemphigoid IgG auto-antibodies (see Section 6).

Pigmentosus. Hyperpigmented, dark-brown macules in sun-exposed areas and flexural folds. In Latin Americans and other dark-skinned populations. Significant similarity or perhaps identity with ashy dermatosis (see Fig. 13-12).

Actinicus. Papular LP lesions arise in sun-exposed sites, especially the dorsa of hands and arms.

Ulcerative. LP may lead to therapy-resistant ulcers, particularly on the soles, requiring skin grafting.

Mucous Membranes. Some 40–60% of individuals with LP have oropharyngeal involvement (see Section 33).

Reticular LP. Reticulate (netlike) pattern of lacy white hyperkeratosis on buccal mucosa (see Section 35), lips (Fig. 14-23A), tongue, gingiva; the most common pattern of oral LP. Erosive or Ulcerative LP. Superficial erosion with/without overlying fibrin clot; occurs on tongue and buccal mucosa (see Section 33); shiny red painful erosion of gingiva (desquamative gingivitis) (see Section 33) or lips (Fig. 14-23A). Carcinoma may very rarely develop in mouth lesions.

Genitalia. Papular (see Section 34) agminated, annular, or erosive lesions arise on penis (especially glans), scrotum, labia majora, labia minora, vagina.

Hair and Nails. Scalp. Follicular LP, atrophic scalp skin with scarring alopecia. (See Section 33.) Nails. Destruction of nail fold and nail bed with longitudinal splintering (see Section 32).

Lichen Planus–Like Eruptions

LP-like eruptions closely mimic typical LP, both clinically and histologically. They occur as a clinical manifestation of chronic GVHD, in dermatomyositis (DM), and as cutaneous manifestations of malignant lymphoma but may also develop as the result of therapy with certain drugs and after industrial use of certain compounds (see Section 23).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Clinical findings confirmed by histopathology.

Papular LP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, eczematous dermatitis, lichenoid GVHD; single lesions: superficial basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease (in situ squamous cell carcinoma).

Hypertrophic LP. Psoriasis vulgaris, lichen simplex chronicus, prurigo nodularis, stasis dermatitis, Kaposi sarcoma.

Mucous Membranes. Leukoplakia, pseudomembranous candidiasis (thrush), HIV-associated hairy leukoplakia, lupus erythematosus, bite trauma, mucous patches of secondary syphilis, pemphigus vulgaris, bullous pemphigoid (see Section 35).

Drug-Induced LP. See Section 23.

Laboratory Examination

Dermatopathology. Inflammation with hyperkeratosis, increased granular layer, irregular acanthosis, liquefaction degeneration of the basal cell layer, and band-like mononuclear infiltrate that hugs the epidermis. Keratinocyte apoptosis (colloid, Civatte bodies) found at the dermal–epidermal junction. Direct immunofluorescence reveals heavy deposits of fibrin at the junction and IgM and, less frequently, IgA, IgG, and C3 in the colloid bodies.

Course

Cutaneous LP usually persists for months, but in some cases, for years; hypertrophic LP on the shins and oral LP often for decades. The incidence of oral squamous cell carcinoma in individuals with oral LP is increased (5%).

Management

Local Therapy

Glucocorticoids. Topical glucocorticoids with occlusion for cutaneous lesions. Intralesional triamcinolone (3 mg/mL) is helpful for symptomatic cutaneous or oral mucosal lesions and lips. Cyclosporine and Tacrolimus Solutions. Retention “mouthwash” for severely symptomatic oral LP.

Systemic Therapy

Cyclosporine. In very resistant and generalized cases, 5 mg/kg per day will induce rapid remission, quite often not followed by recurrence.

Glucocorticoids. Oral prednisone is effective for individuals with symptomatic pruritus, painful erosions, dysphagia, or cosmetic disfigurement. A short, tapered course is preferred: 70 mg initially, tapered by 5 mg/d.

Systemic Retinoids (Acitretin). 1 mg/kg per day is helpful as adjunctive measure in severe (oral, hypertrophic) cases, but usually additional topical treatment is required.

PUVA Photochemotherapy

In individuals with generalized LP or cases resistant to topical therapy.

Other Treatments

Mycophenolate mofetil, heparin analogues (enoxaparin) in low doses have antiproliferative and immunomodulatory properties; azathioprine.

Epidemiology

Age of Onset. Third and fourth decades.

Prevalence. Highest in Turkey (80–420 patients in 100,000), Japan, Korea, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, southern Europe. Rare in northern Europe, United States (0.12–0.33 in 100,000).

Sex. Males > females, but dependent on ethnic background.

Pathogenesis

Etiology unknown. In the eastern Mediterranean and East Asia, HLA-B5 and HLA-B51 association; in the United States and Europe, no consistent HLA association. The lesions are the result of leukocytoclastic (acute) and lymphocytic (late) vasculitis.

Clinical Manifestation

Painful ulcers erupt in a cyclic fashion in the oral cavity and/or genital mucous membranes. Orodynophagia and oral ulcers may persist/recur weeks to months before other symptoms appear.

Skin and Mucous Membranes. Aphthous Ulcers. Punched-out ulcers (3 to >10 mm) with rolled or overhanging borders and necrotic base (Fig. 14-24); red rim; occur in crops (2–10) on oral mucous membrane (100%) (Fig. 14-24), vulva, penis, and scrotum (Figs. 14-25 and 14-26); very painful.

Figure 14-24. Behçet disease Oral aphthous ulcers. (A) These are highly painful, punched-out ulcers with a necrotic base on the buccal mucosa and lower and upper fornix in this 28-year-old Turkish male (arrow). (B) A punched-out ulcer on the tongue of another patient (arrow).

Figure 14-25. Behçet disease: genital ulcers Multiple large aphthous-type ulcers on the labial and perineal skin. In addition, this 25-year-old patient of Turkish extraction had aphthous ulcers in the mouth and previously experienced an episode of uveitis.

Figure 14-26. Behçet disease A large, punched-out ulcer on the scrotum of a 40-year-old Korean. The patient also had aphthous ulcers in the mouth and pustules on the thighs and buttocks.

Figure 14-27. Revised International Criteria for Behçet Disease (International Team for the Revision of ICBD; coordinator, F. Davatchi) according to (A) the classification tree format and (B) the traditional format. BD, Behçet disease; GU, genital ulcer; OA, oral aphthous ulcer. [Modified from Zouboulis CC. Adamantiades-Behçet disease, in Wolff K et al. (eds.): Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 7th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2008:1620–1622.]

Erythema Nodosum-Like Lesions. Painful inflammatory nodules on the arms and legs (40%) (see Section 7).

Other. Inflammatory pustules, superficial thrombophlebitis, inflammatory plaques resembling those in Sweet syndrome (see Section 7), pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions (see Section 7), palpable purpuric lesions of necrotizing vasculitis (see below).

Systemic Findings. Eyes. Leading cause of morbidity. Posterior uveitis, anterior uveitis, retinal vasculitis, vitreitis, hypopyon, secondary cataracts, glaucoma, neovascularization.

Musculoskeletal. Nonerosive, asymmetric oli-goarthritis.

Neurologic. Onset delayed, occurring in one quarter of patients. Meningoencephalitis, benign intracranial hypertension, cranial nerve palsies, brainstem lesions, pyramidal/extrapyramidal lesions, psychosis.

Vascular. Aneurysms, arterial occlusions, venous thrombosis, varices; hemoptysis. Coronary vasculitis: myocarditis, coronary arteritis, endocarditis, valvular disease.

GI Tract. Aphthous ulcers throughout.

Laboratory Examinations

Dermatopathology. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis of blood vessel walls in acute early lesions; lymphocytic vasculitis in late lesions.

Pathergy Test. Positive pathergy test read by physician at 24 or 48 h, after skin puncture with a sterile needle. Leads to inflammatory pustule.

HLA Typing. Significant association with HLA-B5 and HLA-B51, in Japanese, Koreans, and Turks, and in the Middle East.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made according to the Revised International Criteria for Behçet disease (Fig. 14-26).

Differential Diagnosis. Oral and genital ulcers: Viral infection [HSV, varicella-zoster virus (VZV)], hand-foot-and-mouth disease, herpangina, chancre, histoplasmosis, squamous cell carcinoma.

Course and Prognosis

Highly variable course, with recurrences and remissions; the mouth lesions are always present; remissions may last for weeks, months, or years. In the eastern Mediterranean and East Asia, severe course, one of the leading causes of blindness. With CNS involvement, there is a higher mortality rate.

Management

Aphthous Ulcers. Potent topical glucocorticoids. Intralesional triamcinolone, 3–10 mg/mL, injected into ulcer base. Thalidomide, 50–100 mg po in the evening. Colchicine, 0.6 mg po two to three times a day. Dapsone, 50–100 mg/d po.

Systemic Involvement. Prednisone with or without azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine alone, chlorambucil, cyclosporine.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Rare. Incidence >6 cases per million, but this is based on hospitalized patients and does not include individuals without muscle involvement. Juvenile and adult (>40 years) onset.

Etiology. Unknown. In persons >55 years of age, may be associated with malignancy.

Clinical Spectrum. Ranges from DM with only cutaneous inflammation (amyopathic DM) to polymyositis with only muscle inflammation. Cutaneous involvement occurs in 30–40% of adults and 95% of children with DM/polymyositis. For classification, see Table 14-2.

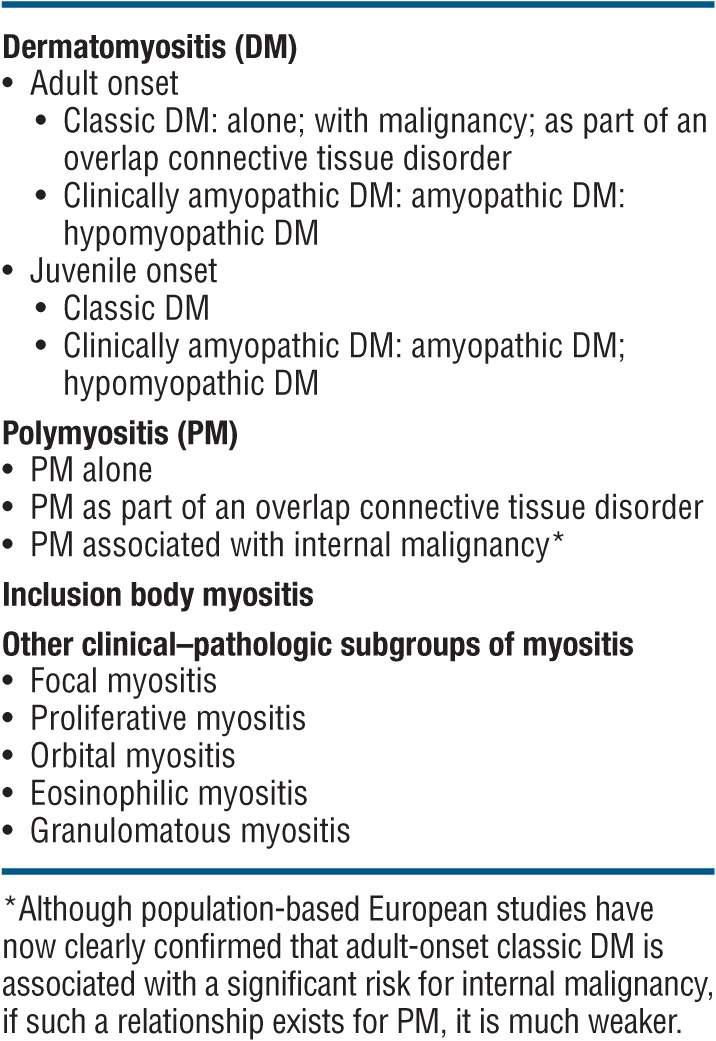

TABLE 14-2 COMPREHENSIVE CLASSIFICATION OF IDIOPATHIC INFLAMMATORY DERMATOMYOPATHIES

Clinical Manifestation

Symptoms. + Photosensitivity. Manifestations of skin disease may precede myositis or vice versa; often, both are detected at the same time. Muscle weakness, difficulty in rising from supine position, climbing stairs, raising arms over head, turning in bed. Dysphagia; burning and pruritus of the scalp.

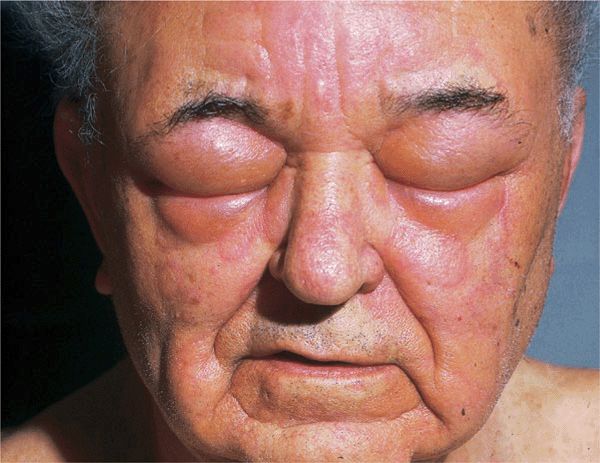

Skin Lesions. Periorbital heliotrope (reddish purple) flush, usually associated with some degree of edema (Fig. 14-28). May extend to involve scalp (+ nonscarring alopecia), entire face (Fig. 14-29A), upper chest, and arms.

Figure 14-28. Dermatomyositis Heliotrope (reddish purple) erythema of upper eyelids and edema of the lower lids. This 55-year-old female had experienced severe muscle weakness of the shoulder girdle and presented with a lump in the breast that proved to be carcinoma.

Figure 14-29. Dermatomyositis (A) Violaceous erythema and edema on the face, particularly in the periorbital and malar regions. The patient could barely lift his arms and could not climb stairs. (B) Violaceous erythema and Gottron papules on the dorsa of the hands and fingers, especially over the interphalangeal joints, where there are also small ulcers. Periungual erythema and telangiectasias.

In addition, papular dermatitis with varying degrees of violaceous erythema in the same sites. Flat-topped, violaceous papules (Gottron papules) with various degrees of atrophy on the nape of the neck and shoulders and over the knuckles and interphalangeal joints (Fig. 14-29B). Note: In lupus, lesions usually occur in the interarticular region of the fingers (see Fig. 14-34A). Periungual erythema with telangiectasia, thrombosis of capillary loops, infarctions. Lesions over elbows and knuckles may evolve into erosions and ulcers (Fig. 14-29B) that heal with stellate scarring (particularly in juvenile DM with vasculitis). Long-lasting lesions may evolve into poikiloderma (mottled discoloration with red, white, and brown) (Fig. 14-30). Calcification in subcutaneous/fascial tissues common later in course of juvenile DM (Fig. 14-31), particularly about elbows, trochanteric, and iliac region (calcinosis cutis); may evolve into calcinosis universalis.

Figure 14-30. Dermatomyositis, juvenile onset, poikiloderma There is mottled, reticular brownish pigmentation and telangiectasia plus small white scars. Note striae on trochanteric areas due to systemic glucocorticoid therapy.

Figure 14-31. Dermatomyositis Calcinosis over the iliac crest. There are stone hard nodules, two of which have ulcerated and reveal a chalk white mass at the base. Upon squeezing, they will exude white paste.

Figure 14-34. Acute SLE (A) Red-to-violaceous, well-demarcated papules and plaques on the dorsa of the fingers and hands, characteristically sparing the skin overlying the joints. This is an important differential diagnostic sign when considering dermatomyositis, which characteristically involves the skin over the joints (compare with Fig. 14-29B). (B) Palmar erythema mainly on the fingertips. This is pathognomonic.

Muscle. ± Muscle tenderness, ±muscle atrophy. Progressive muscle weakness affecting proximal/limb girdle muscles.

Occasional involvement of facial/bulbar, pharyngeal, and esophageal muscles. Deep tendon reflexes within normal limits.

Other Organs. Interstitial pneumonitis, cardiomyopathy arthritis, particularly in juvenile DM (20–65%).

Disease Association. Patients >50 years of age with DM have a higher than expected risk for malignancy, particularly ovarian cancer in females. Also carcinoma of the breast, broncho-pulmonary, and GI tract.

Laboratory Examinations

Chemistry. Elevation of creatine phosphokinase (65%), aldolase (40%), lactate dehydrogenase, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase.

Autoantibodies. Autoantibodies to 155 kDa and/or Se in 80% to 140 kDa in 58% and to Jo-1 in 20% and to (low specificity) antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in 40%.

Urine. Elevated 24-h creatine excretion (>200 mg/24 h).

Electromyography. Increased irritability on insertion of electrodes, spontaneous fibrillations, pseudomyotonic discharges, positive sharp waves.

MRI. MRI of muscles reveals focal lesions.

ECG. Evidence of myocarditis; atrial, ventricular irritability; atrioventricular block.

X-Ray. Chest: ± interstitial fibrosis. Esophagus: reduced peristalsis.

Pathology. Skin. Flattening of epidermis, hydropic degeneration of basal cell layer, edema of upper dermis, scattered inflammatory infiltrate, PAS-positive fibrinoid deposits at dermalepidermal junction, accumulation of acid mucopolysaccharides in dermis (all these are compatible with DM but are not diagnostic).

Muscle. Biopsy shoulder/pelvic girdle; one that is weak or tender. Histology—segmental necrosis within muscle fibers with loss of cross striations; myositis. Vasculitis is seen in juvenile DM.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Skin signs plus proximal muscle weakness with two of three laboratory criteria, i.e., elevated serum “muscle enzyme” levels, characteristic electromyographic changes, diagnostic muscle biopsy. Differential diagnosis is to lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, steroid myopathy, trichinosis, toxoplasmosis.

Course and Prognosis

Prognosis guarded but with treatment, it is relatively good except in patients with malignancy and those with pulmonary involvement. With aggressive immunosuppressive treatment, the 8-year survival rate is 70–80%. A better prognosis is seen in individuals who receive early systemic treatment. The most common causes of death are malignancy, infection, cardiac, and pulmonary disease. Successful treatment of an associated neoplasm is often followed by improvement/resolution of DM.

Management

Prednisone. 0.5–1 mg/kg body weight per day. Taper when “muscle enzyme” levels approach normal. Best if combined with azathioprine, 2–3 mg/kg per day. Note: Steroid myopathy may occur after 4–6 weeks of therapy.

Alternatives. Methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents. High-dose IV immunoglobulin bolus therapy (2 g/kg body weight given over 2 days) at monthly intervals spares glucocorticoid doses to achieve or maintain remissions.

ICD-10: E85.3

ICD-10: E85.3 Amyloidosis is an extracellular deposition in various tissues of amyloid fibril proteins and of a protein called amyloid P component (AP); the identical component of AP is present in the serum and is called SAP. These amyloid deposits can affect normal body function.

Amyloidosis is an extracellular deposition in various tissues of amyloid fibril proteins and of a protein called amyloid P component (AP); the identical component of AP is present in the serum and is called SAP. These amyloid deposits can affect normal body function. Systemic AL amyloidosis, also known as primary amyloidosis, occurs in patients with B cell or plasma cell dyscrasias and multiple myeloma in whom fragments of monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains form amyloid fibrils.

Systemic AL amyloidosis, also known as primary amyloidosis, occurs in patients with B cell or plasma cell dyscrasias and multiple myeloma in whom fragments of monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains form amyloid fibrils. Clinical features of AL include a combination of macroglossia and cardiac, renal, hepatic, and gastrointestinal (GI) involvement, as well as carpal tunnel syndrome and skin lesions. These occur in 30% of patients, and since they occur early in the disease, they are an important clue to the diagnosis.

Clinical features of AL include a combination of macroglossia and cardiac, renal, hepatic, and gastrointestinal (GI) involvement, as well as carpal tunnel syndrome and skin lesions. These occur in 30% of patients, and since they occur early in the disease, they are an important clue to the diagnosis. Systemic AA amyloidosis (reactive) occurs in patients after chronic inflammatory disease, in whom the fibril protein is derived from the circulating acute-phase lipoprotein known as serum amyloid A.

Systemic AA amyloidosis (reactive) occurs in patients after chronic inflammatory disease, in whom the fibril protein is derived from the circulating acute-phase lipoprotein known as serum amyloid A. There are few or no characteristic skin lesions in AA amyloidosis, which usually affects the liver, spleen, kidneys, and adrenals.

There are few or no characteristic skin lesions in AA amyloidosis, which usually affects the liver, spleen, kidneys, and adrenals. In addition, skin manifestations may also be associated with a number of (rare) heredofamilial syndromes.

In addition, skin manifestations may also be associated with a number of (rare) heredofamilial syndromes. Localized cutaneous amyloidosis is not uncommon, presents with typical cutaneous manifestations, and has no systemic involvement.

Localized cutaneous amyloidosis is not uncommon, presents with typical cutaneous manifestations, and has no systemic involvement. ICD-10: E85

ICD-10: E85

Rare, occurs in many, but not all, patients with multiple myeloma and B cell dyscrasia.

Rare, occurs in many, but not all, patients with multiple myeloma and B cell dyscrasia. Skin Lesions: Smooth, waxy papules (

Skin Lesions: Smooth, waxy papules (

Systemic Manifestations: Fatigue, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, malaise, dyspnea; symptoms related to hepatic, renal, and GI involvement; paresthesia related to carpal tunnel syndrome, neuropathy.

Systemic Manifestations: Fatigue, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, malaise, dyspnea; symptoms related to hepatic, renal, and GI involvement; paresthesia related to carpal tunnel syndrome, neuropathy. General Examination: Kidney—nephrosis; nervous system—peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome; cardiovascular—partial heart block, congestive heart failure; hepatic—hepatomegaly; GI—diarrhea, sometimes hemorrhagic, malabsorption; lymphadenopathy.

General Examination: Kidney—nephrosis; nervous system—peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome; cardiovascular—partial heart block, congestive heart failure; hepatic—hepatomegaly; GI—diarrhea, sometimes hemorrhagic, malabsorption; lymphadenopathy. Laboratory: May reveal thrombocytosis >500,000/μL Proteinuria and increased serum creatinine; hypercalcemia. Increased IgG. Monoclonal protein in two-thirds of patients with primary or myeloma-associated amyloidosis. Bone marrow: myeloma.

Laboratory: May reveal thrombocytosis >500,000/μL Proteinuria and increased serum creatinine; hypercalcemia. Increased IgG. Monoclonal protein in two-thirds of patients with primary or myeloma-associated amyloidosis. Bone marrow: myeloma. Dermatopathology: accumulation of faintly eosinophilic masses of amyloid in the papillary body near the epidermis, in the papillary and reticular dermis, in sweat glands, around and within blood vessel walls. Immunohistochemistry to assess the proportion of kappa and lambda light chains.

Dermatopathology: accumulation of faintly eosinophilic masses of amyloid in the papillary body near the epidermis, in the papillary and reticular dermis, in sweat glands, around and within blood vessel walls. Immunohistochemistry to assess the proportion of kappa and lambda light chains. ICD-10: E85

ICD-10: E85

A reactive type of amyloidosis.

A reactive type of amyloidosis. Occurs in any disorder associated with a sustained acute-phase response.

Occurs in any disorder associated with a sustained acute-phase response. 60% have inflammatory arthritis. The rest, other chronic inflammatory infective or neoplastic disorders.

60% have inflammatory arthritis. The rest, other chronic inflammatory infective or neoplastic disorders. Amyloid fibrils are derived from cleavage fragments of the circulating acute-phase reactant serum amyloid A protein.

Amyloid fibrils are derived from cleavage fragments of the circulating acute-phase reactant serum amyloid A protein. Presents with proteinuria followed by progressive renal dysfunction; nephrotic syndrome.

Presents with proteinuria followed by progressive renal dysfunction; nephrotic syndrome. There are no characteristic skin lesions in AA amyloidosis.

There are no characteristic skin lesions in AA amyloidosis.

Three varieties of localized amyloidosis that are unrelated to the systemic amyloidoses.

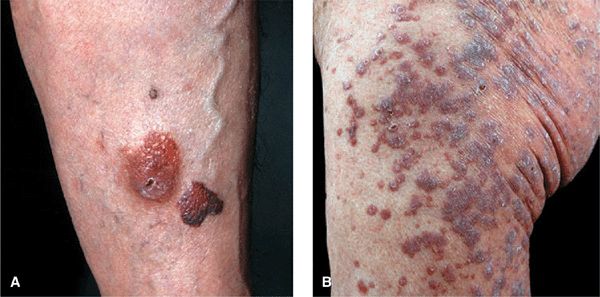

Three varieties of localized amyloidosis that are unrelated to the systemic amyloidoses. Nodular amyloidosis: single or multiple, smooth, nodular lesions with or without purpura on limbs, face, or trunk (

Nodular amyloidosis: single or multiple, smooth, nodular lesions with or without purpura on limbs, face, or trunk (

Lichenoid amyloidosis: discrete, very pruritic, brownish-red papules on the legs (

Lichenoid amyloidosis: discrete, very pruritic, brownish-red papules on the legs ( Macular amyloidosis: pruritic, gray-brown, reticulated macular lesions occurring principally on the upper back (

Macular amyloidosis: pruritic, gray-brown, reticulated macular lesions occurring principally on the upper back (

In lichenoid and macular amyloidosis, the amyloid fibrils in skin are keratin derived. Although these three localized forms of amyloidosis are confined to the skin and unrelated to systemic disease, the skin lesions of nodular amyloidosis are identical to those that occur in AL, in which amyloid fibrils derive from immunoglobulin light chain fragments.

In lichenoid and macular amyloidosis, the amyloid fibrils in skin are keratin derived. Although these three localized forms of amyloidosis are confined to the skin and unrelated to systemic disease, the skin lesions of nodular amyloidosis are identical to those that occur in AL, in which amyloid fibrils derive from immunoglobulin light chain fragments. ICD-10:L50

ICD-10:L50

Urticaria is composed of wheals (transient edematous papules and plaques, usually pruritic and due to edema of the papillary body) (

Urticaria is composed of wheals (transient edematous papules and plaques, usually pruritic and due to edema of the papillary body) (

Angioedema is a larger edematous area that involves the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (

Angioedema is a larger edematous area that involves the dermis and subcutaneous tissue ( Urticaria and/or angioedema may be acute recurrent or chronic recurrent.

Urticaria and/or angioedema may be acute recurrent or chronic recurrent. Other forms of urticaria/angioedema are recognized: IgE and IgE receptor dependent, physical, contact, mast cell degranulation related, and idiopathic.

Other forms of urticaria/angioedema are recognized: IgE and IgE receptor dependent, physical, contact, mast cell degranulation related, and idiopathic. In addition, angioedema/urticaria can be mediated by bradykinin, the complement system, and other effector mechanisms.

In addition, angioedema/urticaria can be mediated by bradykinin, the complement system, and other effector mechanisms. Urticarial vasculitis is a special form of cutaneous necrotizing venulitis (see

Urticarial vasculitis is a special form of cutaneous necrotizing venulitis (see  There are some syndromes with angioedema in which urticarial wheals are rarely present (e.g., hereditary angioedema).

There are some syndromes with angioedema in which urticarial wheals are rarely present (e.g., hereditary angioedema). ICD-10:L51

ICD-10:L51

A common reaction pattern of blood vessels in the dermis with secondary epidermal changes.

A common reaction pattern of blood vessels in the dermis with secondary epidermal changes. Manifests clinically as characteristic erythematous iris-shaped papular and vesiculobullous lesions.

Manifests clinically as characteristic erythematous iris-shaped papular and vesiculobullous lesions. Typically involving the extremities (especially the palms and soles) and the mucous membranes.

Typically involving the extremities (especially the palms and soles) and the mucous membranes. Benign course with frequent recurrences.

Benign course with frequent recurrences. Most cases related to herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection.

Most cases related to herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. Recurrences can be prevented by long-term anti-HSV medication.

Recurrences can be prevented by long-term anti-HSV medication. More severe course in EM major.

More severe course in EM major.

Are rare systemic autoinflammatory diseases, autosomal dominant.

Are rare systemic autoinflammatory diseases, autosomal dominant. Include familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS) (

Include familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS) (

Most have mutations in NLRP3.

Most have mutations in NLRP3. Urticaria-like eruptions (

Urticaria-like eruptions ( Histopathology of lesional skin shows edema, dilatation of superficial capillaries, perivascular and perieccrine neutrophilic infiltrates.

Histopathology of lesional skin shows edema, dilatation of superficial capillaries, perivascular and perieccrine neutrophilic infiltrates. Anti-IL-1 therapy is effective.

Anti-IL-1 therapy is effective. ICD-10: L43

ICD-10: L43

Worldwide occurrence; incidence less than 1%, all races.

Worldwide occurrence; incidence less than 1%, all races. LP is an acute or chronic inflammatory dermatosis involving skin and/or mucous membranes.

LP is an acute or chronic inflammatory dermatosis involving skin and/or mucous membranes. Characterized by flat-topped (Latin planus, “flat”), pink to violaceous, shiny, pruritic polygonal papules. The features of the lesions have been designated as the four P’s—papule, purple, polygonal, pruritic.

Characterized by flat-topped (Latin planus, “flat”), pink to violaceous, shiny, pruritic polygonal papules. The features of the lesions have been designated as the four P’s—papule, purple, polygonal, pruritic. Distribution: predilection for flexural aspects of arms and legs, can become generalized.

Distribution: predilection for flexural aspects of arms and legs, can become generalized. In the mouth, milky-white reticulated papules; may become erosive and even ulcerate.

In the mouth, milky-white reticulated papules; may become erosive and even ulcerate. Main symptom: pruritus; in the mouth, pain.

Main symptom: pruritus; in the mouth, pain. Therapy: topical and systemic glucocorticoids, cyclosporine.

Therapy: topical and systemic glucocorticoids, cyclosporine.

Rare; worldwide occurrence, but strongly variable ethnic prevalence.

Rare; worldwide occurrence, but strongly variable ethnic prevalence. It is a perplexing multisystem vasculitic disease with multiorgan involvement.

It is a perplexing multisystem vasculitic disease with multiorgan involvement. Main symptoms are recurrent oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, erythema nodosum, superficial thrombophlebitis, skin pustules, iridocyclitis, and posterior uveitis.

Main symptoms are recurrent oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, erythema nodosum, superficial thrombophlebitis, skin pustules, iridocyclitis, and posterior uveitis. Additional symptoms may be arthritis, epididymitis, ileocecal ulcerations, vascular, and central nervous system (CNS) lesions.

Additional symptoms may be arthritis, epididymitis, ileocecal ulcerations, vascular, and central nervous system (CNS) lesions. Chronic relapsing progressive course with potentially poor prognosis.

Chronic relapsing progressive course with potentially poor prognosis. ICD-10: M33.0

ICD-10: M33.0

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a systemic disease belonging to the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, a heterogeneous group of genetically determined autoimmune diseases targeting the skin and/or skeletal muscles.

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a systemic disease belonging to the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, a heterogeneous group of genetically determined autoimmune diseases targeting the skin and/or skeletal muscles. DM is characterized by violaceous (heliotrope) inflammatory changes +/– edema of the eyelids and periorbital area; erythema of the face, neck, and upper trunk; and flat-topped violaceous papules over the knuckles.

DM is characterized by violaceous (heliotrope) inflammatory changes +/– edema of the eyelids and periorbital area; erythema of the face, neck, and upper trunk; and flat-topped violaceous papules over the knuckles. It is associated with polymyositis, interstitial pneumonitis, and myocardial involvement.

It is associated with polymyositis, interstitial pneumonitis, and myocardial involvement. There is also a DM without myopathy (amyopathic DM) and polymyositis without skin involvement.

There is also a DM without myopathy (amyopathic DM) and polymyositis without skin involvement. Juvenile DM runs a different course and is associated with vasculitis and calcinosis.

Juvenile DM runs a different course and is associated with vasculitis and calcinosis. Adult-onset DM may be associated with internal malignancy.

Adult-onset DM may be associated with internal malignancy. Prognosis is guarded.

Prognosis is guarded.