Intravascular Large Cell Lymphomas

It is yet unclear whether the two phenotypic variants of intravascular large cell lymphoma, namely, the more frequent B-cell type and the exceedingly rare natural killer (NK)/T-cell type, represent different phenotypes of one category of lymphoma or completely different entities. In addition, there is increasing evidence that many CD30+ intravascular large T-cell lymphomas are unrelated to conventional intravascular large cell lymphomas, as they present with tumor cells located within the lymphatic rather than the blood vessels and are characterized by a milder course. In this edition of the book, intravascular large cell lymphomas have been included in the section on cutaneous B cell lymphomas, as in most instances they represent indeed a peculiar type of large B-cell lymphomas. The NK/T-cell and CD30+ variants are included in this chapter as separate entities, because the intravascular location of tumor cells is a least common denominator with the B-cell type, and at present they are not classified separately in lymphoma classifications.

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is considered as a distinct entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [1]. By contrast, the T-cell variant is probably the only lymphoma type that is not covered by any classification. The WHO classification mentions it only with the following words: “Anecdotal cases of intravascular T-cell or NK-cell lymphoma have been reported, but they should be considered a different entity (than intravascular large B-cell lymphoma)” [1]; further details are not provided.

The skin may be the only affected site in intravascular large cell lymphomas, but more frequently the disease presents with generalized lesions and common neurologic symptoms due to involvement of the central nervous system.

Intravascular large cell lymphoma is characterized by the presence of neoplastic cells confined almost exclusively to the lumina of vessels, and it was formerly misinterpreted as a vascular neoplasm (malignant angioendotheliomatosis) [2]. It is still unclear whether cases classified in the past as large B-cell lymphoma recurring as intravascular lymphoma [3, 4] or as “mixed” intravascular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [5] should be included in this category [6].

The reason(s) why neoplastic cells in intravascular large cell lymphoma are confined within the vessels is unclear. Absence of molecules crucial for adhesion of lymphocytes to endothelial cells and migration out of the vessels (CD29, CD54) has been observed in some cases with the B-cell phenotype, leading to the hypothesis that neoplastic lymphocytes in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma are unable to escape outside the vessel walls [7]. Recently, molecular studies demonstrated the expression of angiogenic factors VEGFA, VEGFC, FIGF, and SPP1 by neoplastic cells in one case of cutaneous intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [8]. In one patient, CXCR3 was expressed by tumor lymphocytes, and its ligand CXCL9 was detected in blood vessels, thus providing a further possible explanation for intraluminal location of neoplastic cells [9].

It should be remembered that in a distinct proportion of the reported cases, particularly in the NK/T-cell variant of the disease, the diagnosis of intravascular large cell lymphoma was a retrospective one made first at autopsy.

Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is a malignant proliferation of large B lymphocytes confined within blood vessels. In rare cases the skin may be the only affected site, though more often the lymphoma is disseminated with common involvement of the central nervous system. As already mentioned, cases of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma have been reported in patients with pre-existing cutaneous or, more often, nodal large B-cell lymphoma, probably representing recurrence of the original disease rather than a genuine intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [3, 4].

Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma Colonizing Hemangiomas

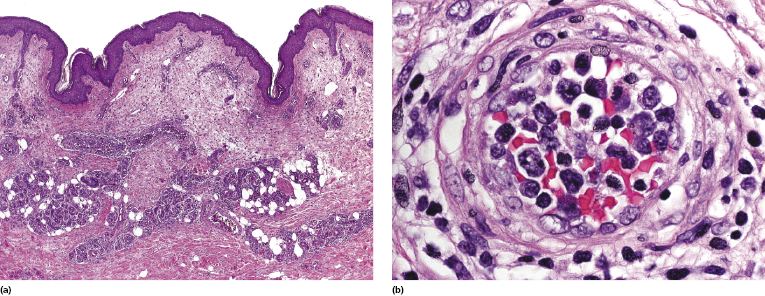

Colonization of capillaries of cutaneous hemangiomas by neoplastic cells of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma has been observed in more cases than pure chance would justify, suggesting that these cells have a special tropism for neoplastic blood vessels [10–16]. Sometimes this is the only manifestation of the lymphoma and no other sites are involved [14–16]. We have observed a woman with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma confined to three out of six capillary hemangiomas that had been surgically removed, and with no other manifestations of the disease [15]. In a similar fashion, neoplastic cells have been detected in the vessels of Kaposi sarcoma and of solid tumors. This is probably one of the most intriguing features of this rare lymphoma, and investigation of such cases may provide some clues concerning the disease.

Clinical Features

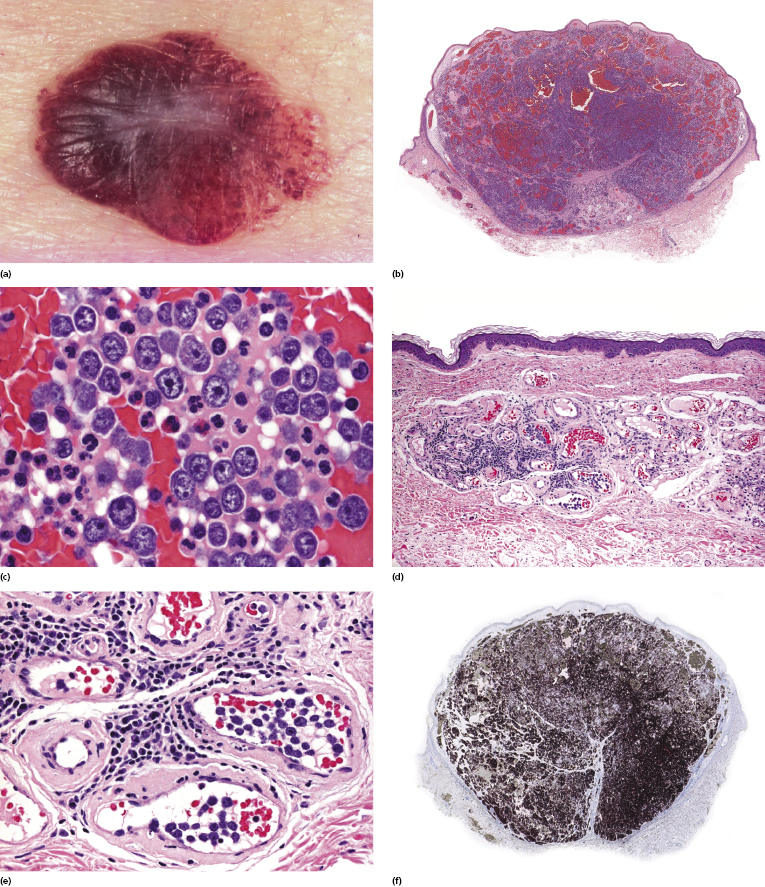

Patients present with indurated, erythematous or violaceous, ill-defined patches and plaques, preferentially located on the trunk and thighs (Fig. 14.1). The clinical appearance is not typical of lymphoma and may sometimes suggest a diagnosis of panniculitis or purpura (Fig. 14.2) [17–21]. Teleangectasia is frequently found in affected areas (Fig. 14.3) [22] and generalized telangiectasia has been observed in one patient [23]. Neurologic symptoms as a sign of involvement of the central nervous system are commonly present [24]. Other organs that are frequently involved are the liver and kidney.

Hemophagocytosis was reported in the majority of Asian patients [25, 26], but not in European ones [27–29]. It has been suggested that hemophagocytosis-associated cases represent a distinct variant of the disease with significantly different clinical features (“Asian” variant of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma), characterized by higher frequency of systemic symptoms (fever, fatigue) and hepatic, splenic, and bone marrow involvement, and lower frequency of neurologic and cutaneous involvement [27]. B symptoms, anemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, and bone marrow involvement are frequently observed in patients with associated hemophagocytic syndrome.

As already mentioned, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma may arise within the vessels of pre-existent capillary hemangiomas (Fig. 14.4).

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

Histology reveals a proliferation of large lymphocytes filling dilated blood vessels within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues, conveying at low power the impression of increased numbers of “thick” vessels within the dermis and sometimes the subcutaneous fat (Fig. 14.5a). A perivascular infiltrate of large atypical cells is present only rarely, and even perivascular reactive infiltrates are sparse or sometimes missing altogether, thus rendering difficult the identification of vessels with only a few intravascular neoplastic cells (see Teaching case 14.1). The malignant cells are large with scant cytoplasm and often with prominent nucleoli (immunoblasts) (Fig. 14.5b).

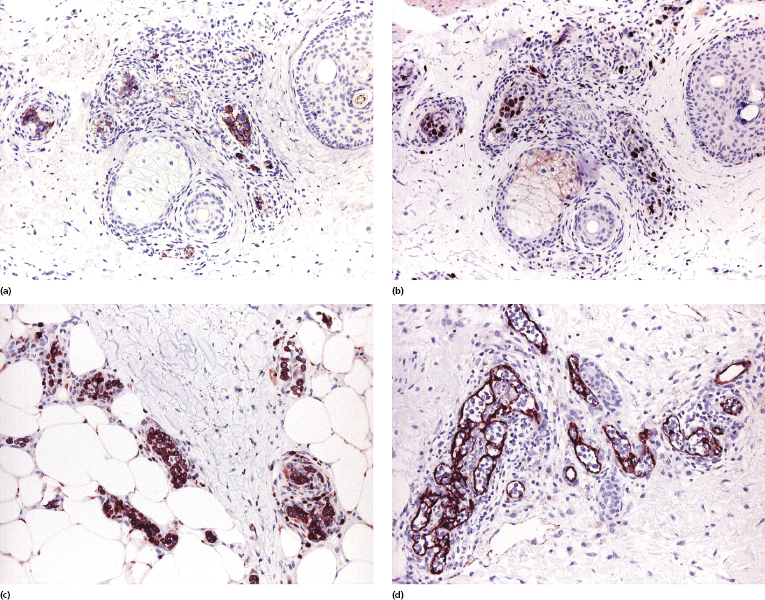

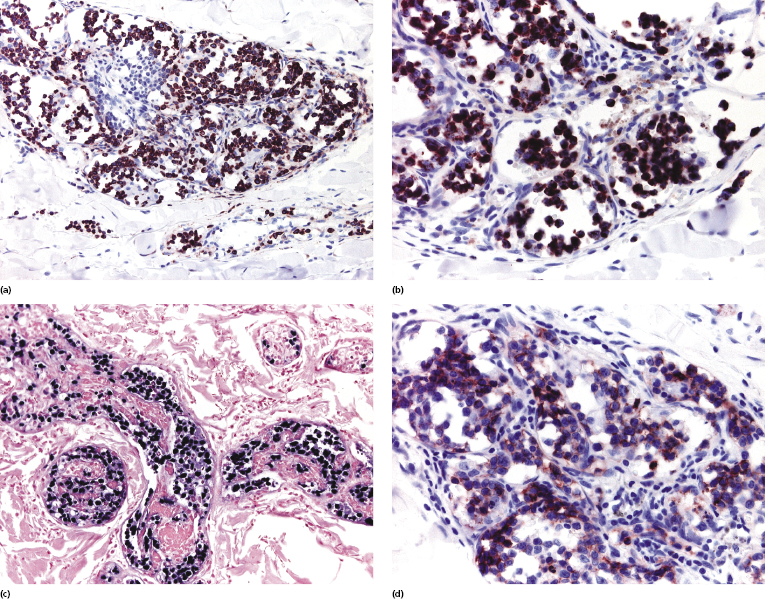

Neoplastic cells are positive for B-cell-associated markers (CD20, CD79a) (Fig. 14.6a), and in a subset of cases show aberrant CD5 expression [30]. Positivity for Bcl-2 and multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1) is observed in the vast majority of cases, highlighting the similarities with other diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (Fig. 14.6b and c). Bcl-6 and CD10 are positive only in a small minority of cases, whereas cyclin D1 is consistently negative. Monoclonal expression of either κ or λ light chain can be demonstrated in the majority of cases on frozen sections of tissue, but detection is usually not possible on routinely fixed material. Positivity for prostatic acid phosphatase has been reported in a small series [31].

Staining with endothelial cell-related antibodies (i.e., CD31, CD34) highlights the characteristic intravascular location of the cells (Fig. 14.6d), which are located in blood vessels (podoplanine-positive lymphatic vessels do not harbor neoplastic cells).

In situ hybridization for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) was negative in a large study [25], but rare positive cases may be observed. Molecular analysis shows monoclonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin (Ig) genes. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) studies revealed karyotype abnormalities in cases of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, but observations are limited to small numbers of cases [32]. Aberrations in chromosomes 1 and 6, and trisomy of 18 have been reported in some patients [33]. A t(14;18) was observed in one case [34].

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma should be distinguished from reactive angioendotheliomatosis, a benign disorder due to an intravascular proliferation of endothelial cells, intralymphatic histiocytosis, a reactive condition characterized by presence of clusters of intralymphatic histiocytes [35], and from so-called benign intravascular proliferation of T-cell lymphoid blasts, an incidental histopathologic finding described rarely as an incidental finding in various skin diseases (see Chapter 26).

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of choice of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is anthracycline-based systemic chemotherapy associated with rituximab (R-CHOP) [26, 36]. It has also been suggested to add drugs with a higher bioavailability in the central nervous system, such as high-dose methotrexate or cytarabine [6, 37]. Autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation has been used in occasional patients with encouraging results [38], but data on large numbers of patients are lacking.

The prognosis of cases limited to the skin seems to be better than that of the generalized (multisystem) disease [39, 40]. Unfavorable prognostic factors are lack of anthracycline-based chemotherapy, age older than 60 years, and thrombocytopenia <100 × 109/L [25]. Positivity for CD5 does not influence the prognosis.

Intravascular Large NK/T-Cell Lymphoma

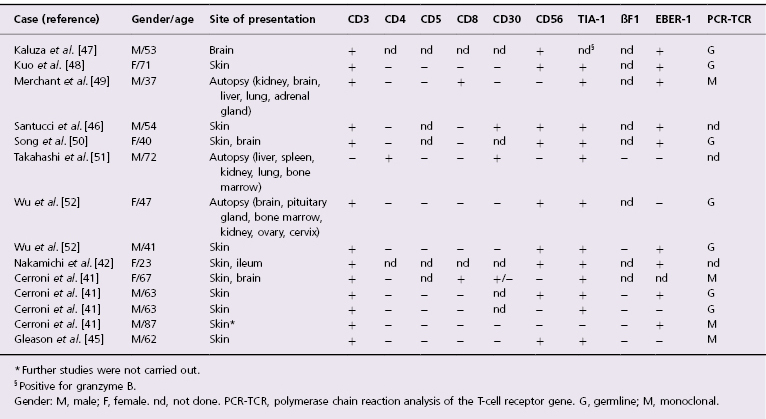

Rarely, cases of cutaneous intravascular large cell lymphoma may show a T-cell or NK-cell phenotype [41–52]. This is probably the rarest form of lymphoma (not only cutaneous), as very few cases have been reported in the literature, and only in 14 of them have sufficient immunophenotypic studies been performed (Table 14.1). In the past, CD30+ cases were included in this group, but there is increasing evidence that most (but not all!) of them represent a different entity (see the section on intralymphatic CD30+ large T-cell lymphoma and Table 14.2 in this chapter). Besides the phenotype, the most striking difference between intravascular large NK/T-cell lymphoma and intravascular large B-cell lymphoma seems to be the much more common association with EBV infection in the NK/T-cell variant [41, 42]. Intravascular large NK/T-cell lymphoma is not covered in the WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, where there is only a brief remark on it within the chapter on intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (see the beginning of this chapter) [1].

Table 14.1 Clinicopathologic features of cases of intravascular NK/T-cell lymphoma reported in the literature with sufficient phenotypic data

Patients are usually elderly adults though a congenital case (detected at autopsy and without skin involvement) has been reported [43]. The clinical presentation and histopathologic features are similar to those seen in the more common B-cell variant.

Neoplastic cells in intravascular large NK/T-cell lymphoma express CD2 and CD3, but are commonly negative for CD5 (Fig. 14.7a). Several studies demonstrated that the vast majority of cases have a cytotoxic NK/T phenotype and are associated with EBV, thus showing some similarities to extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type (Fig. 14.7c) [41, 44, 45]. However, rarely cases are characterized by a T-helper or CD30+ phenotype, and it seems that intravascular large NK/T-cell lymphoma represents a relatively heterogeneous phenotypic entity (as already mentioned, however, many of the CD30+ cases may represent a different lymphoma) [41]. CD56 is expressed by neoplastic cells in the majority of cases (Fig. 14.7d), whereas βF1, a marker of α/β T lymphocytes, was negative in all cases tested [41, 46].

Molecular analysis of the T-cell receptor (TCR) genes rearrangement was conducted only in a few instances, revealing monoclonality in approximately one-third of cases (the negative cases possibly representing those with a genuine NK cell phenotype).

Prognosis and treatment of intravascular large NK/T-cell lymphoma do not seem to differ from those of the B-cell type, but of course anti-CD20 antibodies do not have efficacy in the NK/T-cell variant. Data on treatment are available only for a handful of patients and there are no clear-cut guidelines. The course is very aggressive. The prognosis seems to be better for patients with disease limited to one organ only, as compared to those with disease detected in two or more organs.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree