Precancerous Lesions and Cutaneous Carcinomas

Epithelial Precancerous Lesions and SCCIS

Dysplasia of epidermal keratinocytes in epidermis and squamous mucosa can involve the lower portion of the epidermis or the full thickness. Basal cells mature into dysplastic keratinocytes resulting in a hyperkeratotic papule, or plaque, clinically identified as “keratosis.” A continuum exists from dysplasia to SCCIS to invasive SCC. These lesions have various associated eponyms such as Bowen disease or erythroplasia of Queyrat, which as descriptive morphologic terms are helpful; terms such as UVR- or HPV-associated SCCIS, however, would be more meaningful but can be used only for those lesions with known etiology.

Epithelial precancerous lesions and SCCIS can be classified into UV-induced [solar (actinic) keratoses, lichenoid actinic keratoses, Bowenoid actinic keratoses, and Bowen disease (SCCIS)], HPV-induced [low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) and Bowenoid papulosis (SCCIS)], arsenical-induced (palmoplantar keratoses, Bowenoid arsenical) keratosis, and hydrocarbon (tar) keratoses and thermal keratoses.

Solar or Actinic Keratosis

These single or multiple, discrete, dry, rough, adherent scaly lesions occur on the habitually sun-exposed skin of adults. They can progress to SCCIS, which can then progress to invasive SCC (Fig. 11-1). For a full discussion of this condition, see Section 10.

Figure 11-1. Solar keratoses and invasive squamous cell carcinoma Multiple, tightly adherent dirty looking solar keratoses (see also Figs. 10-25 to 10-27). The large nodule shown here is covered by hyperkeratoses and hemorrhagic crusts; it is partially eroded and firm. This nodule is invasive squamous cell carcinoma. The image is shown to demonstrate the transition from precancerous lesions to frank carcinoma.

Synonym: Solar and actinic keratosis is synonymous.

Figure 11-2. Cutaneous horn: hypertrophic actinic keratosis A hornlike projection of keratin on a slightly raised base in the setting of advanced dermatoheliosis on the upper eyelid in an 85-year-old female. Excision showed invasive SCC at the base of the lesion.

Figure 11-3. Arsenical keratoses (A) Multiple punctate, tightly adherent, and very hard keratoses on the palm. (B) Arsenical keratoses on the back. Multiple lesions are seen here ranging from red to tan, dark brown, and white. The brown lesions are a mix of arsenical keratoses (hard, rough) and small seborrheic keratoses (soft and smooth). The difference can be better felt than seen. The red lesions are small Bowenoid keratoses and Bowen disease (SCCIS, see Fig. 11-4). The white macular areas are slightly depressed and represent superficial atrophie scars from spontaneously shed or treated arsenical keratoses. The entire picture gives the impression of “rain drops in the dust.”

Etiology

UVR, HPV, arsenic, tar, chronic heat exposure, and chronic radiation dermatitis.

Clinical Manifestation

Lesions are most often asymptomatic but may bleed. Nodule formation or onset of pain or tenderness within SCCIS suggests progression to invasive SCC.

Skin Findings. Appears as a sharply demarcated, scaling, or hyperkeratotic macule, papule, or plaque (Fig. 11-4). Pink or red in color, slightly scaling surface or erosions, and can be crusted. Solitary or multiple. Such lesions are called Bowsen disease (Fig. 11-4).

Figure 11-4. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ: Bowen disease (A) A large, sharply demarcated, scaly, and erythematous plaque simulating a psoriatic lesion. (B) A similar psoriasiform plaque with a mix of scales, hyperkeratosis, and hemorrhagc crusts on the surface.

Red, sharply demarcated, glistening macular or plaque-like SCCIS on the glans penis or labia minora are called erythrop>lasia of Queyrat (see Section 36). Anogenital HPV-induced SCCIS may be red, tan, brown, or black in color and are referred to as Bowenoid papulosis (see Section 36). Eroded lesions may have areas of crusting. SCCIS may go undiagnosed for years, resulting in large lesions with annular or polycyclic borders (Fig. 11-5). Once invasion occurs, nodular lesions appear within the plaque and the lesion is then commonly called Bowsen carcinoma (Fig. 11-5).

Distribution. UVR-induced SCCIS commonly arises within a solar keratosis in the setting of photoaging (dermatoheliosis); HPV-induced SCCIS, mostly in the genital area but also periungually, most commonly on the thumb or in the nail bed (see Fig. 10-33 and 34-16).

Figure 11-5. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCCIS): Bowen disease and invasive SCC: Bowen carcinoma A red to orange plaque on the back, sharply defined, with irregular outlines and psoriasiform scale represents SCCIS, or Bowen disease. The red nodule on this plaque indicates that here the lesion is not anymore an in situ lesion but that invasive carcinoma has developed.

Laboratory Examination

Dermatopathology. Carcinoma in situ with loss of epidermal architecture and regular differentiation; keratinocyte polymorphism, single cell dyskeratosis, increased mitotic rate, and multi-nuclear cells. Epidermis may be thickened but basement membrane intact.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis confirmed by dermatopathologic findings. Differential diagnosis includes all well-demarcated pink-red plaque(s): Nummular eczema, psoriasis, seborrheic keratosis, solar keratoses, verruca vulgaris, verruca plana, condyloma acuminatum, superficial BCC, amelanotic melanoma, and Paget disease.

Course and Prognosis

Untreated SCCIS will progress to invasive SCC (Fig. 11-5). In HIV/AIDS, resolves with successful antiretroviral therapy (ART). Lymph node metastasis can occur without demonstrable invasion. Metastatic dissemination from lymph nodes.

Management

Topical Chemotherapy. 5-Fluorouracil cream applied every day or twice daily, with or without tape occlusion, is effective. So is imiquimod, but both require considerable time.

Cryosurgery. Highly effective. Lesions are usually treated more aggressively than solar keratoses, and superficial scarring will result.

Photodynamic Therapy. Effective but still cumbersome and painful.

Surgical Excision Including Mohs Micrographic Surgery. Has the highest cure rate but the greatest chance of causing cosmetically disfiguring scars. It should be done in all lesions where invasion cannot be excluded by biopsy.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Ultraviolet Radiation

Age of Onset. Older than 55 years of age in Caucasians in the United States and Europe; in Australia, New Zealand, in Florida, Southwest and Southern California, Caucasians in their twenties and thirties.

Incidence. Continental United States: 12 per 100,000 white men; 7 per 100,000 white women. Hawaii: 62 per 100,000 whites.

Figure 11-6. Squamous cell carcinoma: predilection sites.

Sex. Males > females, but SCC can occur more frequently on the legs of females.

Exposure. Sunlight. Phototherapy and PUVA (oral psoralen + UVA). Excessive photochemotherapy can lead to promotion of SCC, particularly in patients with skin phototypes I and II or in patients with history of previous exposure to ionizing radiation.

Race. Persons with white skin and poor tanning capacity (skin phototypes I and II) (see Section 10). Brown- or black-skinned persons can develop SCC from numerous etiologic agents other than UVR.

Geography. Most common in areas that have many days of sunshine annually, i.e., in Australia and southwestern United States.

Occupation. Persons working outdoors—farmers, sailors, lifeguards, telephone line installers, construction workers, and dock workers.

Human Papillomavirus

Most commonly oncogenic HPV type-16, -18, -31 but also type-33, -35, -39, -40, and -51 to -60 are associated with epithelial dysplasia, SCCIS, and invasive SCC. HPV-5, -8, -9 have also been isolated from SCCs.

Other Etiologic Factors

Immunosuppression. Solid organ transplant recipients, individuals with chronic immunosuppression of inflammatory disorders, and those with HIV disease are associated with an increased incidence of UVR- and HPV-induced SCCIS and invasive SCCs. SCCs in these individuals are more aggressive than in nonimmunosuppressed individuals.

Chronic Inflammation. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, chronic ulcers, burn scars, chronic radiation dermatitis, and lichen planus of oral mucosa.

Industrial Carcinogens. Pitch, tar, crude paraffin oil, fuel oil, creosote, lubricating oil, and nitrosoureas.

Inorganic Arsenic. Trivalent arsenic had been used in the past in medications such as Asiatic pills, Donovan pills, and Fowler solution (used as a treatment for psoriasis or anemia). Arsenic is still present in drinking water in some geographic regions (West Bengal and Bangladesh).

Clinical Manifestation

Slowly evolving—any isolated keratotic or eroded papule or plaque in a suspect patient that persists for over a month is considered a carcinoma until proved otherwise. Also, a nodule evolving in a plaque that meets the clinical criteria of SCCIS (Bowen disease), a chronically eroded lesion on the lower lip or on the penis, or nodular lesions evolving in or at the margin of a chronic venous ulcer or within chronic radiation dermatitis. Note that SCC usually is always asymptomatic. Potential carcinogens often can be detected only after detailed history.

Rapidly evolving—invasive SCC can erupt within a few weeks and there is often painful and/or tender.

For didactic reasons, two types can be distinguished:

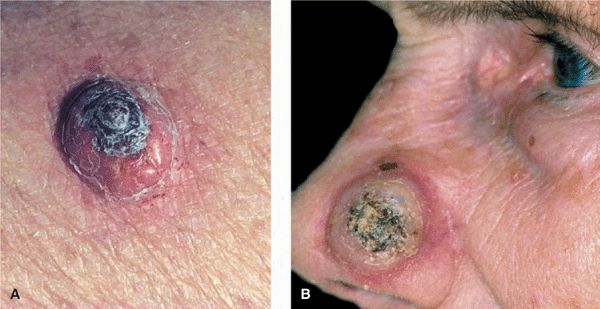

1. Highly differentiated SCCs, which practically always show signs of keratinization either within or on the surface (hyperkeratosis) of the tumor. These are firm or hard upon palpation (Figs. 11-7 to 11-9 and Figs. 11-11 and 11-12).

2. Poorly differentiated SCCs, which do not show signs of keratinization and clinically appear fleshy, granulomatous, and consequently are soft upon palpation (Figs. 11-5 and 11-10).

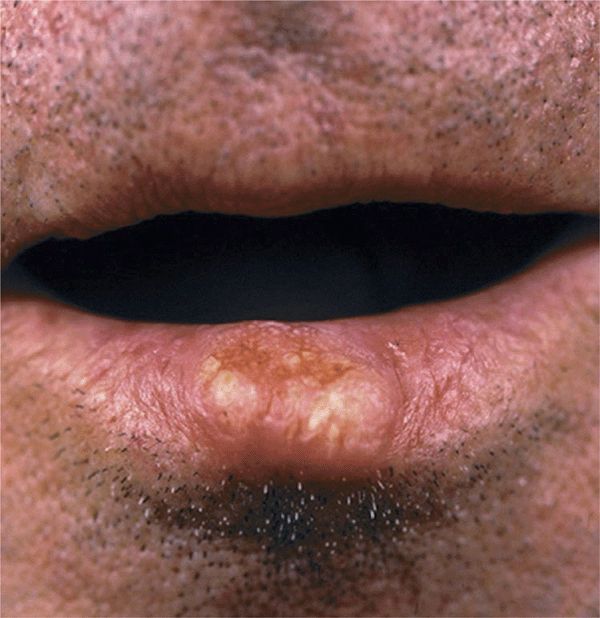

Figure 11-7. Squamous cell carcinoma: invasive on the lip A large but subtle nodule, which is better felt than seen, on the vermilion border of the lower lip with areas of yellowish hyperkeratosis. This nodule can be felt to infiltrate the entire lip.

Differentiated SCC

Lesions. Indurated papule, plaque, or nodule (Figs. 11-1, 11-7 and 11-8); adherent thick keratotic scale or hyperkeratosis (Figs. 11-1, 11-7–11-9 and 11-12); when eroded or ulcerated, the lesion may have a crust in the center and a firm, hyperkeratotic, elevated margin (Figs. 11-6 and 11-9). Horny material may be expressed from the margin or the center of the lesion (Figs. 11-8, 11-9 and 11-11). Erythematous, yellowish, skin color; hard; polygonal, oval, round (Figs. 11-7 and 11-11), or umbilicated and ulcerated.

Distribution. Usually isolated but may be multiple. Usually exposed areas (Fig. 11-6). Sun-induced keratotic and/or ulcerated lesions especially on the bald scalp (Fig. 11-1), cheeks, nose, lower lips (Fig. 11-7), ears (Fig. 11-12), preauricular area, dorsa of the hands (Fig. 11-11), forearms, trunk, and shins (females).

Figure 11-8. Squamous cell carcinoma: (SCC) A round nodule, firm and indolent with a central black eschar. Note yellowish color in the periphery of the tumor indicating the presence of keratin. The SCC shown in Fig. 11-7 and here is hard and occurs on the lower lip. SCC hardly occurs on the upper lip because this is shaded from the sun. SCC on the lip is easily distinguished from nodular BCC because BCC does not develop hyperkeratosis or keratinization inside the tumor and does not occur on the vermilion lip.

Figure 11-9. Squamous cell carcinoma, well differentiated (A) A nodule on the lower arm covered with a dome-shaped black hyperkeratosis. (B) A large, round, hard nodule on the nose with central hyperkeratosis. Neither lesion can be clinically distinguished from keratoacanthoma (see Fig. 11-15).

Other Physical Findings. Regional lymphadenopathy due to metastases.

Special Features. In UV-related SCC evidence of dermatoheliosis and solar keratoses. SCCs of the lips develop from leukoplasia or actinic cheilitis; in 90% of cases they are found on the lower lip (Figs. 11-7 and 11-8). In chronic radiodermatitis, they arise from radiationinduced keratoses (see Fig. 10-33); in individuals with a history of chronic intake of arsenic, from arsenical keratoses. Differentiated (i.e., hyperkeratotic) SCC due to HPV on genitalia; SCC due to excessive PUVA therapy on lower extremities (pretibial) or on genitalia. SCCs in scars from burns, in chronic stasis ulcers of long duration, and in sites of chronic inflammation are often difficult to identify. Suspicion is indicated when nodular lesions are hard and show signs of keratinization.

Special form: carcinoma cuniculatum, usually on the soles, highly differentiated, HPV-related but can also occur in other settings (Fig. 11-13); verrucous carcinoma, also florid oral papillomatosis, on the oral mucous membranes (see Section 35).

Histopathology. SCCs with various grades of anaplasia and keratinization.

Undifferentiated SCC

Lesions. Fleshy granulating, easily vulnerable, erosive papules and nodules, and papillomatous vegetations (Fig. 11-10). Ulceration with a necrotic base and soft, fleshy margin. Bleeds easily, crusting; red; soft; polygonal, irregular, often cauliflower-like.

Figure 11-10. Squamous cell carcinoma, undifferentiated There is a circular, dome-shaped reddish nodule with partly eroded surface on the temple of a 78-year-old male. The lesion shows no hyperkeratoses and is soft and friable. When scraped it bleeds easily.

Distribution. Isolated but also multiple, particularly on the genitalia, where they arise from erythroplasia and on the trunk (Fig. 11-5), lower extremities, or face, where they arise from Bowen disease.

Miscellaneous Other Skin Changes. Lymphadenopathy as evidence of regional metastases is far more common than with differentiated, hyperkeratotic SCCs.

Histopathology. Anaplastic SCC with multiple mitoses and little evidence of differentiation and keratinization.

Figure 11-11. Squamous cell carcinoma, advanced, well differentiated, on the hand of a 65-year-old farmer The big nodule is smooth, very hard upon palpation, and shows a yellowish color, focally indicating keratin in the body of the nodule. If the lesion was incised in the yellowish areas, a yellowish-white material (keratin) could be expressed.

Figure 11-12. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), highly differentiated, on the ear There is a relatively large plaque covered by adherent hard hyperkeratoses. Although SCCs are in general not painful, lesions on the helix or anthelix usually are, as was the case in this 69-year-old man.

Figure 11-13. Squamous cell carcinoma (carcinoma cuniculatum) in a patient with peripheral neuropathy due to leprosy A large fungating, partially necrotic, and hyperkeratotic tumor on the sole of the foot. The lesion had been considered a neuropathic ulcer, ascribed to leprosy, but continued growing and became elevated and ulcerated.

Differential Diagnosis

Any persistent nodule, plaque, or ulcer, but especially when these occur in sun-damaged skin, on the lower lips, in areas of radiodermatitis, in old burn scars, or on the genitalia, must be examined for SCC. Keratoacanthoma (KA) may be clinically indistinguishable from differentiated SCC (Fig. 11-15).

Management

Surgery. Depending on localization and extent of lesion, excision with primary closure, skin flaps, or grafting. Mohs micrographic surgery in difficult sites. Radiotherapy should be performed only if surgery is not feasible.

Course and Prognosis

Recurrence and Metastases. SCC causes local tissue destruction and has a potential for metastases. Metastases are directed to regional lymph nodes and appear 1–3 years after initial diagnosis. In-transit metastases occur. In solid organ transplant recipients, metastasis can be present when SCC is diagnosed/detected or shortly after. SCC in the skin has an overall metastatic rate of 3-4%. High-risk SCCs are defined as having a diameter >2 cm, a level of invasion >4 mm, and Clark levels IV or V1; tumor involvement of bone, muscle, and nerve (so-called neurotropic SCC, occurs frequently on the forehead and scalp); location on ear, lip, and genitalia; tumors arising in a scar or following ionizing radiation are usually highly undifferentiated. Cancers arising in chronic osteomyelitis sinus tracts, in burn scars, and in sites of radiation dermatitis have a metastatic rate of 31%, 20%, and 18%, respectively. SCC arising in solar keratoses has the lowest potential for metastasis.

SCCs in Immunosuppression. Organ transplant recipients have a markedly increased incidence of NMSCs, primarily high risk SCC, which is 40–50 times greater than in the general population. Risk factors include skin type, cumulative sun exposure, age at transplantation, male sex, HPV infections, the degree and length of immunosuppression, and the type of immunosuppressant. Lesions are often multiple, usually in sun-exposed sites but also in the genital, anal, and perigenital regions (Fig. 11-14). These tumors grow rapidly and are aggressive; in one series of heart-transplant patients from Australia, 27% died of skin cancer.

Figure 11-14. Squamous cell carcinomas in a renal transplant recipient on the upper thigh and buttock There are multiple firm nodules, partially ulcerated. The patient had smaller, similar lesions elsewhere on the body. Since he had psoriasis and had therefore spent considerable time in the sun, the lesions in the sun-exposed sides were probably due to UVR. The lesion shown here was probably initiated by HPV as he had a similar lesion perianally and on the glans. The ulcer on the right buttock is an excision site from which sutures were prematurely removed.

Patients with AIDS have only a slight increased risk of NMSC. In one series a fourfold increase in their risk of developing lip SCC was noted. However, SCC of the anus is significantly increased in this population (see also Section 27).

ICD-10: L85.8

ICD-10: L85.8

A cutaneous horn (CH) is a clinical entity having the appearance of an animal horn with a papular or nodular base and a keratotic cap of various shapes and lengths (

A cutaneous horn (CH) is a clinical entity having the appearance of an animal horn with a papular or nodular base and a keratotic cap of various shapes and lengths ( CHs most commonly represent hypertrophic solar keratoses. Non-precancerous CH formation can also occur in seborrheic keratoses and warts.

CHs most commonly represent hypertrophic solar keratoses. Non-precancerous CH formation can also occur in seborrheic keratoses and warts. CHs usually arise within areas of dermatoheliosis on the face, ear, dorsum of hands, or forearms, and shins.

CHs usually arise within areas of dermatoheliosis on the face, ear, dorsum of hands, or forearms, and shins. Clinically, CHs vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters (

Clinically, CHs vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters ( Histologically, there is usually hypertrophic actinic keratosis, SCCIS, or invasive SCC at the base. Because of the possibility of invasive SCC, a CH should always be excised.

Histologically, there is usually hypertrophic actinic keratosis, SCCIS, or invasive SCC at the base. Because of the possibility of invasive SCC, a CH should always be excised. ICD-10: L85.8

ICD-10: L85.8

Appear decades after chronic arsenic ingestion (medicinal, occupational, or environmental exposure).

Appear decades after chronic arsenic ingestion (medicinal, occupational, or environmental exposure). Arsenical keratoses have the potential to become SCCIS or invasive SCC. These are currently being seen in West Bengal and Bangladesh where drinking water may still contain arsenic.

Arsenical keratoses have the potential to become SCCIS or invasive SCC. These are currently being seen in West Bengal and Bangladesh where drinking water may still contain arsenic. Two types: punctate, yellow papules on palms and soles (

Two types: punctate, yellow papules on palms and soles ( Treatment—as for solar keratoses.

Treatment—as for solar keratoses. ICD-10: M8070/2

ICD-10: M8070/2

Presents as solitary or multiple macules, papules, or plaques, which may be hyperkeratotic or scaling.

Presents as solitary or multiple macules, papules, or plaques, which may be hyperkeratotic or scaling. SCCIS is most often caused by UVR or HPV infection.

SCCIS is most often caused by UVR or HPV infection. Commonly arises in epithelial dysplastic lesions such as solar keratoses or HPV-induced squamous epithelial lesions (SIL) (see

Commonly arises in epithelial dysplastic lesions such as solar keratoses or HPV-induced squamous epithelial lesions (SIL) (see  Pink or red, sharply defined scaly plaques on the skin are called Bowen disease; similar but usually non-scaly lesions on the glans and vulva are called erythroplasia (see

Pink or red, sharply defined scaly plaques on the skin are called Bowen disease; similar but usually non-scaly lesions on the glans and vulva are called erythroplasia (see  Anogenital HPV-induced SCCIS is referred to as Bowenoid papulosis.

Anogenital HPV-induced SCCIS is referred to as Bowenoid papulosis. Untreated SSCIS may progress to invasive SCC. With HPV-induced SCCIS in HIV/AIDS, lesions often resolve completely with successful antiretroviral therapy and immune reconstitution.

Untreated SSCIS may progress to invasive SCC. With HPV-induced SCCIS in HIV/AIDS, lesions often resolve completely with successful antiretroviral therapy and immune reconstitution. Treatment is topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, cryosurgery, CO2 laser evaporation, or excision, including Mohs micrographic surgery.

Treatment is topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, cryosurgery, CO2 laser evaporation, or excision, including Mohs micrographic surgery. ICD-10: M8076/2-3

ICD-10: M8076/2-3

SCC of the skin is a malignant tumor of keratinocytes, arising in the epidermis.

SCC of the skin is a malignant tumor of keratinocytes, arising in the epidermis. SCC usually arises in epidermal precancerous lesions (see above) and, depending on etiology and level of differentiation, varies in its aggressiveness.

SCC usually arises in epidermal precancerous lesions (see above) and, depending on etiology and level of differentiation, varies in its aggressiveness. The lesion is a plaque or a nodule with varying degrees of keratinization in the nodule and/or on the surface. Thumb rule: undifferentiated SCC is soft and has no hyperkeratosis; differentiated SCC is hard on palpation and has hyperkeratosis.

The lesion is a plaque or a nodule with varying degrees of keratinization in the nodule and/or on the surface. Thumb rule: undifferentiated SCC is soft and has no hyperkeratosis; differentiated SCC is hard on palpation and has hyperkeratosis. The majority of UVR-induced lesions are differentiated and have a low rate of distant metastasis in otherwise healthy individuals. Undifferentiated SCC and SCC in immunosuppressed individuals are more aggressive with a greater incidence of metastasis.

The majority of UVR-induced lesions are differentiated and have a low rate of distant metastasis in otherwise healthy individuals. Undifferentiated SCC and SCC in immunosuppressed individuals are more aggressive with a greater incidence of metastasis. Treatment is by surgery.

Treatment is by surgery.