Photosensitivity, Photo-Induced Disorders, and Disorders by Ionizing Radiation

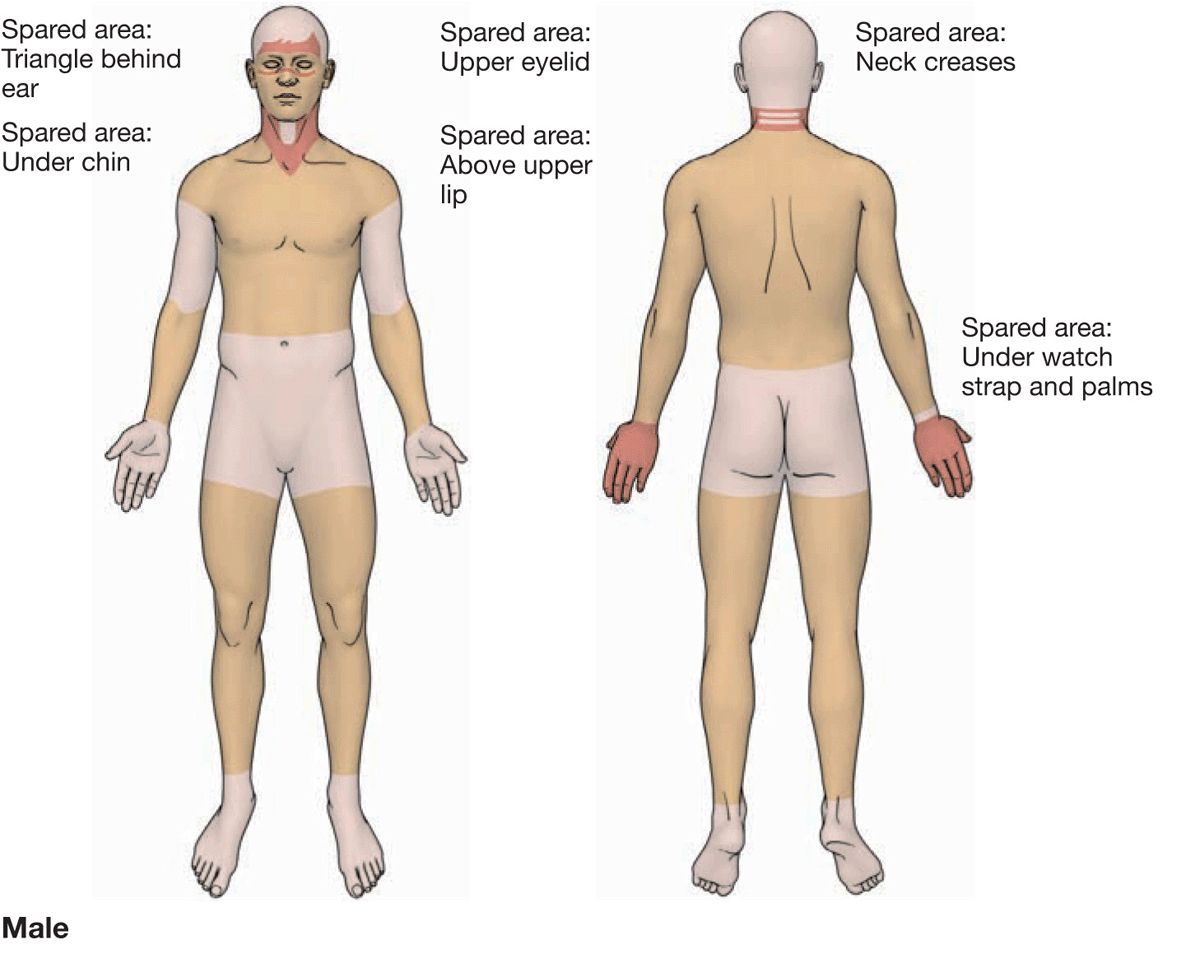

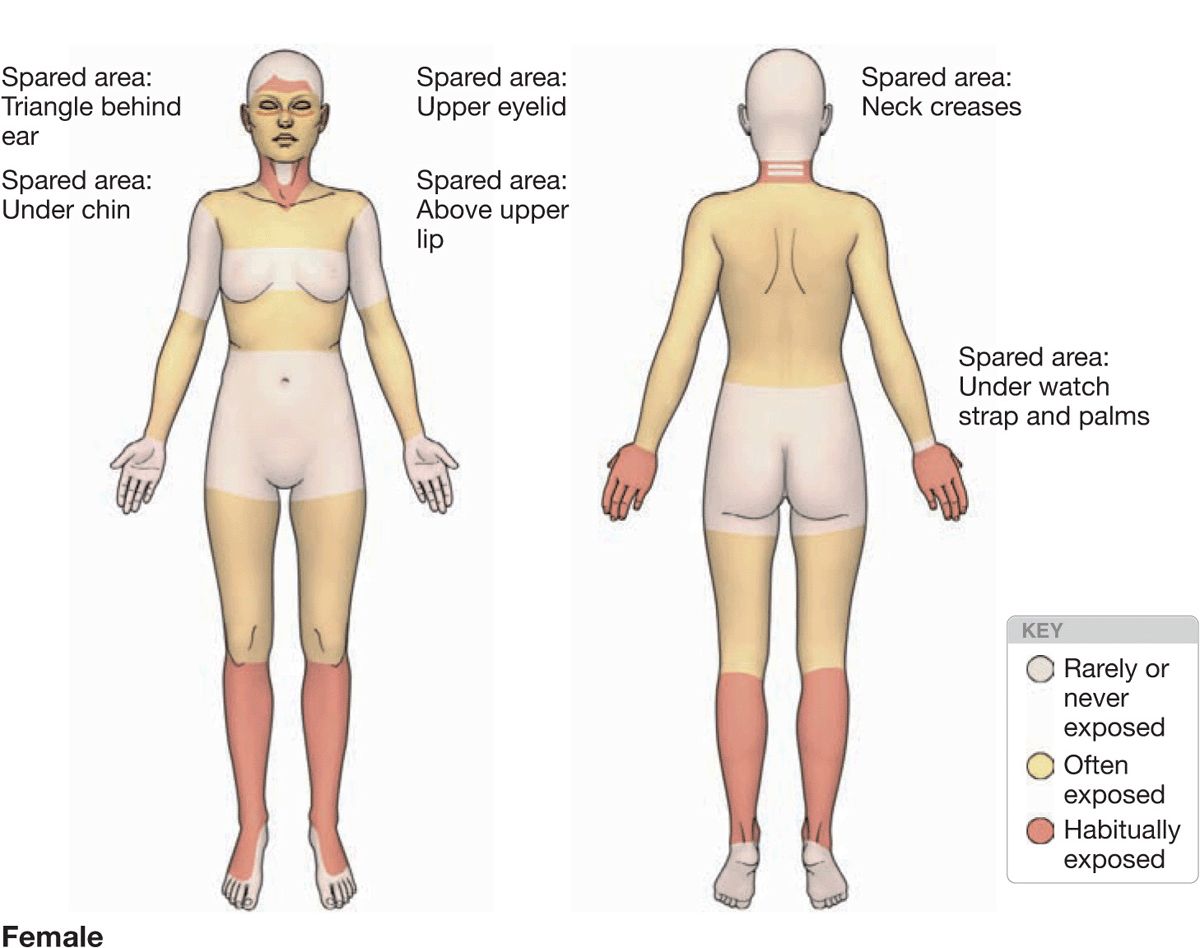

Figure 10-1. Variations in solar exposure on different body areas.

TABLE 10-1 SIMPLIFIED CLASSIFICATION OF SKIN REACTIONS TO SUNLIGHT

Basics of Clinical Photomedicine

The main culprit of solar radiation-induced skin pathology is the ultraviolet (UV) portion of the solar spectrum. Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is divided into two principal types: UVB (290–320 nm), the “sunburn spectrum,” and UVA (320–400 nm) that is subdivided into UVA-1 (340–400 nm) and UVA-2 (320–340 nm). The unit of measurement of sunburn is the minimum erythema dose (MED), which is the minimum UV exposure that produces an erythema 24 h after a single exposure. UVB erythema develops in 6–24 h and fades within 72–120 h. UVA erythema develops in 4–16 h and fades within 48–120 h.

Variations in Sun Reactivity in Normal Persons: Fitzpatrick Skin Phototypes (Table 10-2). Sunburn is seen most frequently in individuals who have pale white or white skin and a limited capacity to develop inducible, melanin pigmentation (tanning) after exposure to UVR. Basic skin color is divided into white, brown, and black. Not all persons with white skin have the same capacity to develop tanning, and this fact is the principal basis for the classification of “white” persons into four skin phototypes (SPT). The SPT is based on the basic skin color and on a person’s own estimate of sunburning and tanning (Table 10-2).

TABLE 10-2 CLASSIFICATION OF FITZPATRICK’s SKIN PHOTOTYPES (SPT)

SPT I persons usually have pale white skin color, blond or red hair, and blue eyes; but, in fact, they may have dark brown hair and brown eyes. SPT I persons sunburn easily with short exposures and do not tan. SPT II persons sunburn easily but tan with difficulty, while SPT III persons may have some sunburn with short exposures but can develop marked tanning. SPT IV persons tan with ease and do not sunburn with short exposures. Persons with constitutive brown skin are termed SPT V and with black skin SPT VI. Note that sunburn depends on the amount of UVR energy absorbed. Thus, with excessive sun exposure, even SPT VI person can have a sunburn.

Epidemiology

Sunburn depends on the amount of UVR energy delivered and the susceptibility of the individual (SPT). It will therefore occur more often around midday, with decreasing latitude, increasing altitude, and decreasing SPT. Thus, the “ideal” setting for a sunburn to occur would be an SPT I individual (highest susceptibility) on Mt. Kenya (high altitude, close to the equator) at noon (UVR is highest). Of course, sunburn can occur at any latitude, but the probability for it to occur decreases with increasing distance from the equator.

Pathogenesis

Molecules that absorb UVR for UVB sunburn erythema are not known, but damage to DNA may be the initiating event. The mediators that cause the erythema include histamine for both UVA and UVB. In UVB erythema, other mediators include TNF-α, serotonin, prostaglandins, nitric oxide, lysosomal enzymes, and kinins. TNF-α can be detected as early as 1 h after exposure.

Clinical Manifestation

Skin Symptoms. Onset depends on intensity of exposure. Pruritus may be severe even in mild sunburn; pain and tenderness occur with severe sunburn.

Constitutional Symptoms. Some SPT I and II persons develop headache and malaise even after short exposures. In severe sunburn, the patient is “toxic”—with fever, weakness, lassitude, and a rapid pulse rate.

Skin Lesions. Confluent bright erythema always confined to sun-exposed areas and thus sharply marginated at the border between exposed and covered skin (Fig. 10-2). Develops after 6 h and peaks after 24 h. Edema, vesicles, and even bullae; always uniform erythema and no “rash,” as occurs in most photoallergic reactions. As edema and erythema fade vesicles and blisters dry to crusts, which are then shed.

Distribution. Strictly confined to areas of exposure; sunburn can occur in areas covered with clothing, depending on the degree of UV transmission through clothing, the level of exposure, and the SPT of the person.

Mucous Membranes. Sunburn is frequent on the vermilion border of the lips and can occur on the tongue in mountain climbers who stick their tongue out panting.

Figure 10-2. Acute sunburn Painful, tender, bright erythema with mild edema of the upper back with sharp demarcation between the sun-exposed and sun-protected white areas.

Laboratory Examinations

Dermatopathology. “Sunburn” cells in the epidermis (apoptotic keratinocytes); exocytosis of lymphocytes, vacuolization of melanocytes, and Langerhans cells. Dermis: endothelial cell swelling of superficial blood vessels.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

History of UVR exposure and sites of reaction on exposed areas. Phototoxic erythema: history of medications that induce phototoxic erythema. SLE can cause a sunburn-type erythema. Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) causes erythema, vesicles, edema, and purpura.

Course and Prognosis

Sunburn, unlike thermal burns, cannot be classified on the basis of depth, i.e., first-, second-, and third-degree because 3° burns after UVR do not occur—therefore, there is no scarring. A permanent reaction from severe UV burns is mottled depigmentation, probably related to the destruction of melanocytes, and eruptive solar lentigines (see Fig. 10-23).

Figure 10-3. Phototoxic drug-induced photosensitivity (A) Massive edema and erythema in the face of a 17-year-old girl who was treated with demethylchlortetracycline for acne. (B) Dusky erythema with blistering on the dorsa of both hands in a patient treated with piroxicam.

Management

Prevention. SPT I or II should avoid sunbathing, especially between 11 AM and 2 PM. Clothing: UV-screening cloth garments. There are now many highly effective topical chemical filters (sunscreens) in lotion, gel, and cream formulations.

Topical. Cool wet dressings and topical glucocorticoids.

Systemic. Acetylsalicylic acid, indomethacin, and NSAIDs.

Severe Sunburn. Bed rest. If very severe, a “toxic” patient may require hospitalization for fluid replacement, prophylaxis of infection.

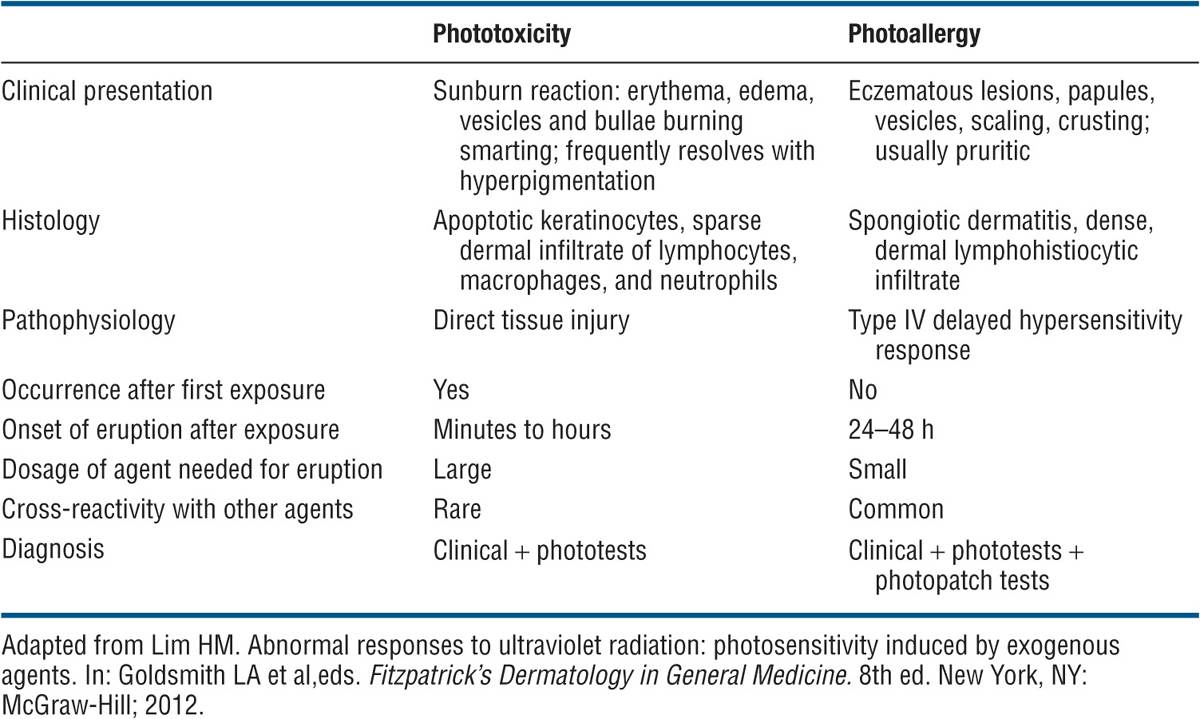

TABLE 10-3 CHARACTERISTICS OF PHOTOTOXICITY AND PHOTOALLERGY

Systemic Phototoxic Dermatitis

ICD-9:692.79  ICD-10:656.0

ICD-10:656.0

Epidemiology

Occurs in everyone after ingestion of a sufficient dose of a photosensitizing drug and subsequent UVR.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

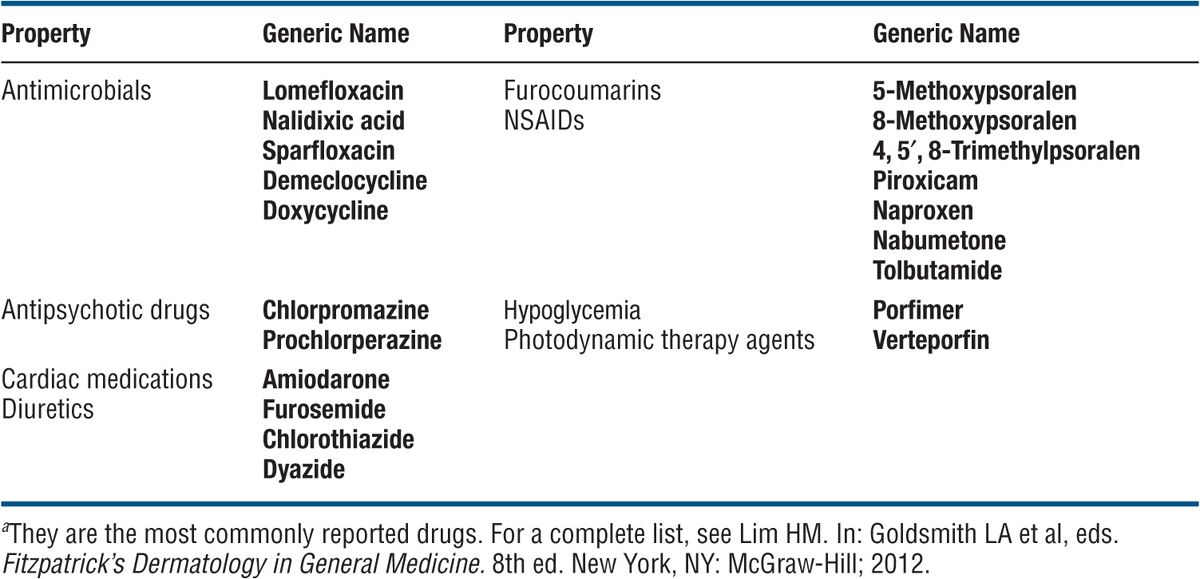

Toxic photoproducts such as free radicals or reactive oxygen species such as singlet oxygen. Principal sites of damage are nuclear DNA cell membranes (plasma, lysosomal, mitochondrial). The action spectrum is UVA. Drugs eliciting systemic phototoxic dermatitis are listed in Table 10-4. Some drugs causing phototoxic reactions can also elicit photoallergic reactions ¡see below).

TABLE 10-4 THE MOST COMMON SYSTEMIC PHOTOTOXIC AGENTS3

Clinical Manifestation

An “exaggerated sunburn” after solar or UVR exposure that normally would not elicit a sunburn in that particular individual. Occurs usually within hours after exposure, with some agents such as psoralens after 24 h, and peaking at 48 h. Skin symptoms: burning, stinging, and pruritus.

Skin Lesions. Early. The skin lesions are those of an “exaggerated sunburn.” Erythema, edema (Fig. 10-3A), and vesicle and bulla formation (Fig. 10-3B) confined to areas exposed to light. An eczematous reaction is not seen in phototoxic reactions.

Special Presentations: Pseudoporphyria. With some drugs there is little erythema but pronounced blistering and skin fragility with erosions (see Fig. 23-11) and, upon repeated exposures, healing with milia, particularly on the dorsa of hands and lower arms. Clinically indistinguishable from porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) (see Fig. 10-12) except for the lack of facial hypertrichosis—hence the term pseudoporphyria (see Section 23),

Nails. Subungual hemorrhage and photoony-cholysis can occur with certain drugs (psoralens, demethylchlortetracycline, benoxaprofen).

Pigmentation. Marked brown epidermal melanin pigmentation may occur in the course. With certain drugs especially, chlorpromazine and amiodarone, a slate gray dermal melanin pigmentation develops (see Fig. 23-9),

Laboratory Examinations

Dermatopathology. Inflammation, “sunburn cells” (apoptotic keratinocytes) in the epidermis, epidermal necrobiosis, intraepidermal, and subepidermal vesiculation

Phototesting. Template test sites are exposed to increasing doses of UVA (phototoxic reactions are almost always due to UVA) while patient is on the drug. The UVA MED will be much lower than that for normal individuals of the same SPT. After drug has been eliminated from the skin, a repeat UVA phototest will reveal an increase in the UVA MED.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

History of exposure to drugs and morphologic changes in the skin characteristic of phototoxic drug eruptions. Differential diagnosis includes regular sunburn, phototoxic reactions due to excess of endogenous porphyrins, and photosensitivity due to other diseases, e.g., SLE.

Course and Prognosis

Phototoxic drug sensitivity seriously limits or excludes the use of important drugs: diuretics, antihypertensive agents, and drugs used in psychiatry. Phototoxic drug reactions disappear after cessation of drug.

Management

As for sunburn.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Common. Usually in spring and summer or all year in tropical climates.

Race. All skin colors; brown- and black-skinned persons may develop only marked spotty dark pigmentation without erythema or bullous lesions.

Occupation. Celery pickers, carrot processors, gardeners [exposed to carrot greens or to “gas plant” (Dictamnus albus)], and bartenders (lime juice) who are exposed to sun in outside bars. Nonoccupational: housewives and users of perfumes containing oil of bergamot; persons walking and children playing in meadows develop PPD on the legs; meadow grass contains agrimony

Etiology. Phototoxic reaction caused by photoactive furocoumarins (psoralens) contained in the plants.

Clinical Manifestation

The patient gives a history of exposure to certain plants (lime, lemon, wild parsley, celery, giant hogweed, parsnips, carrot greens, figs). Use of perfumes containing oil of bergamot (which contains bergapten, 5-methoxypsoralen) may develop streaks of pigmentation only in areas where the perfume was applied. This is called berloque dermatitis (French: berloque, “pendant”).

Skin Symptoms. Smarting, sensation of sunburn, pain, later pruritus.

Skin Lesions. Acute: erythema, edema, vesicles, and bullae (Fig. 10-4). Lesions may appear pseudopapular before vesicles are evident (Fig. 10-5). Often bizarre streaks and artificial patterns (Fig. 10-5). On the sites of contact, especially the arms, legs, and face. Residual hyperpigmentation in bizarre streaks (berloque dermatitis) (Fig. 10-6),

Figure 10-4. Phytophotodermatitis (plant + light): acute with blisters These bullae were the result of exposure to umbilliferae and the sun. This 50-year-old housewife was weeding her garden on a sunny day. Umbilliferae contain bergapten (5-methoxypsoralen), which is a potent topical phototoxic chemical.

Figure 10-5. Phytophotodermatitis In a 48-year-old man who was sunbathing in a meadow. Before vesicles and blisters arise erythematous lesions may appear raised, giving the false impression of being papular. Note streaky pattern.

Figure 10-6. Berloque dermatitis The patient had applied a fragrant bath oil to her shoulders and chest but showered only the front of her body before going into the sun. The bath oil contained oil of bergamot, and pigmentation is now noted where it trickled down from the shoulders to the buttocks. (Courtesy of Dr. Thomas Schwarz.)

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

By recognition of pattern and careful history. Differential diagnosis is primarily acute irritant contact dermatitis, with streaky pattern. Poison ivy dermatitis (see Fig. 2-8), but this is eczematous.

Course

May be an important occupational problem, as in celery pickers. The acute eruption has a short life and fades spontaneously but the pigmentation may last for many weeks.

Management

Wet dressings may be indicated in the acute vesicular stage. Topical glucocorticoids.

Epidemiology

Laboratory Examination

Age of Onset. More common in adults.

Race. All SPTs and colors.

Incidence. Photoallergic drug reactions occur much less frequently than do phototoxic drug reactions.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Topically applied chemical/drug plus UVA radiation. The chemicals are disinfectants, antimicrobials, agents in sunscreens, perfumes in aftershaves, or whiteners (Table 10-5). The chemical agent present in the skin absorbs photons and forms a photoproduct; this then binds to a soluble or membrane-bound protein to form an antigen to which a type IV immune response is elicited. Photoallergy is elicited only in those who have been sensitized. It can also be induced by systemic administration of a drug and elicited by topical administration of the same drug, and vice versa. UVA is always required.

TABLE 10-5 TOPICAL PH0T0ALLERGENSa

Clinical Manifestation

Skin Lesions. Highly pruritic. Acute photoallergic reaction patterns are clinically indistinguishable from allergic contact dermatitis (Fig. 10-7): papular, vesicular, scaling, and crusted. Occasionally there can also be a lichenoid eruption similar to lichen planus. In chronic drug photoallergy, there is scaling, lichenification, and marked pruritus mimicking atopic dermatitis or, again, chronic allergic contact dermatitis (Fig. 10-7)

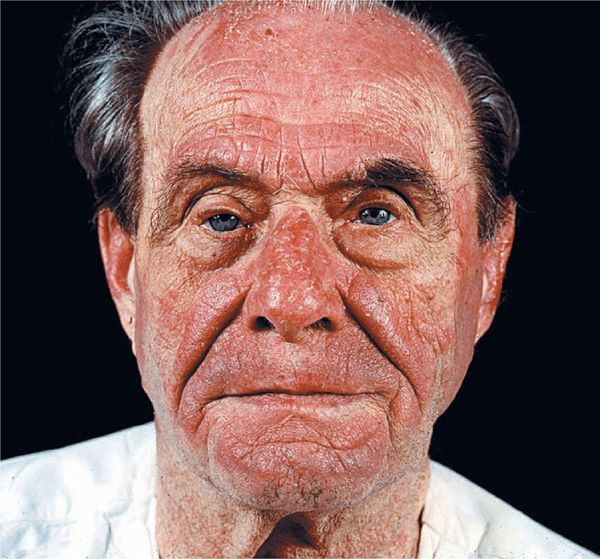

Figure 10-7. Photoallergic drug-induced photosensitivity This 60-year-old male shows an eczematous dermatitis in the face. He was taking trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Note relative sparing of eyelids (protected by sunglasses), under the nose, and the area under the lower lip (shaded areas).

Distribution. Confined primarily to areas exposed to light (distribution pattern of photosensitivity), but there may be spreading onto adjacent nonexposed skin. Of diagnostic help is the fact that in the face the upper eyelids, the area under the nose, and a thin strip of skin between the lower lip and the chin are often spared (shaded areas) (Fig. 10-7).

Laboratory Examination

Dermatopathology. Epidermal spongiosis with lymphocytic infiltration.

Diagnosis

History of exposure to drug, the allergic contact dermatitis pattern of the eruption, and its confinement to sun-exposed sites. Diagnosis is verified by the photopatch test: Photoallergens are applied in duplicate to the skin and covered. After 24 h, one set of the duplicate test sites is exposed to UVA, while the other set remains covered; test sites are read for reactions after 48-96 h. An eczematous reaction in the irradiated site but not in the nonirradiated site confirms photoallergy to the particular agent tested.

Course and Prognosis

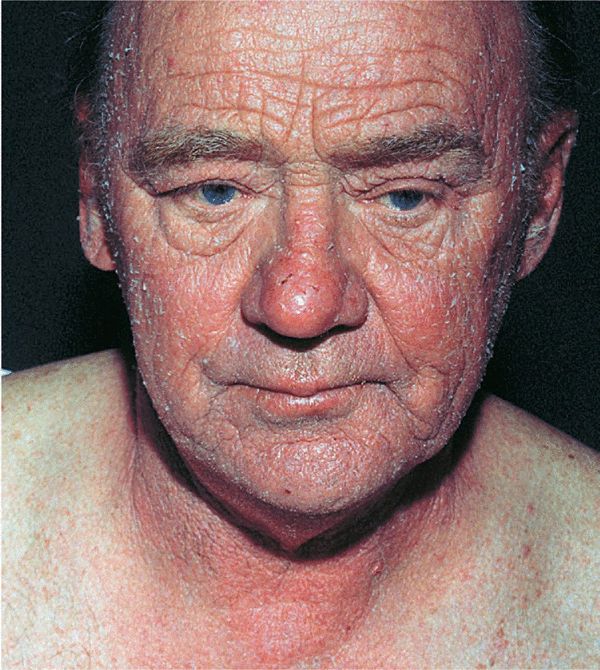

Photoallergic dermatitis can persist for months to years. This is known as chronic actinic dermatitis (formerly persistent light reaction) (Fig. 10-8). In chronic actinic dermatitis, the action spectrum usually broadens to involve also UVB, and the condition persists despite discontinuation of the causative photoallergen, with each new UV exposure aggravating the condition. Chronic eczema-like lichenified and extremely itchy confluent plaques result (Fig. 10-8), which lead to disfigurement and a distressing situation for the patient. As the condition is now independent of the original photoallergen and is aggravated by each new solar exposure, avoidance of photoallergen does not cure the disease.

Figure 10-8. Drug-induced photosensitivity: chronic actinic dermatitis (formerly persistent light eruption) Erythematous plaques confined to the face and neck, sparing the shoulders. This male has excruciating pruritus.

Management

In severe cases, immunosuppression (azathioprine plus glucocorticoids or oral cyclosporine) is required.

ICD-10: L56.8

ICD-10: L56.8 ICD-10:L55

ICD-10:L55

Sunburn is an acute, delayed, and transient inflammatory response of normal skin after exposure to UVR from sunlight or artificial sources.

Sunburn is an acute, delayed, and transient inflammatory response of normal skin after exposure to UVR from sunlight or artificial sources. By nature, it is a phototoxic reaction.

By nature, it is a phototoxic reaction. Sunburn is characterized by erythema (

Sunburn is characterized by erythema ( ICD-10: L56.0

ICD-10: L56.0 Interaction of UVR with a chemical or drug within the skin.

Interaction of UVR with a chemical or drug within the skin. Two mechanisms: phototoxic reactions, which are photochemical reactions and photoallergic reactions, where a photoallergen is formed that initiates an immunologic response and manifests in skin as a type IV immunologic reaction.

Two mechanisms: phototoxic reactions, which are photochemical reactions and photoallergic reactions, where a photoallergen is formed that initiates an immunologic response and manifests in skin as a type IV immunologic reaction. The difference between phototoxic and photoallergic eruptions is that the former manifests like an irritant (toxic) contact dermatitis or sunburn and the latter like an allergic eczematous contact dermatitis (see

The difference between phototoxic and photoallergic eruptions is that the former manifests like an irritant (toxic) contact dermatitis or sunburn and the latter like an allergic eczematous contact dermatitis (see  ICD-10: L56.0

ICD-10: L56.0 An adverse reaction of the skin that results from simultaneous exposure to certain drugs (via ingestion, injection, or topical application) and to UVR or visible light or chemicals that may be therapeutic, cosmetic, industrial, or agricultural.

An adverse reaction of the skin that results from simultaneous exposure to certain drugs (via ingestion, injection, or topical application) and to UVR or visible light or chemicals that may be therapeutic, cosmetic, industrial, or agricultural. Two types of reaction: (1) systemic phototoxic dermatitis, occurring in individuals systemically exposed to a photosensitizing agent (drug) and subsequent UVR, and (2) local phototoxic dermatitis, occurring in individuals topically exposed to the photosensitizing agent and subsequent UVR.

Two types of reaction: (1) systemic phototoxic dermatitis, occurring in individuals systemically exposed to a photosensitizing agent (drug) and subsequent UVR, and (2) local phototoxic dermatitis, occurring in individuals topically exposed to the photosensitizing agent and subsequent UVR. Both are exaggerated sunburn responses (erythema, edema, vesicles, and/or bullae).

Both are exaggerated sunburn responses (erythema, edema, vesicles, and/or bullae). Systemic phototoxic dermatitis occurs in all UVR-exposed sites; local phototoxic dermatitis only in the topical application sites.

Systemic phototoxic dermatitis occurs in all UVR-exposed sites; local phototoxic dermatitis only in the topical application sites. ICD-10: L56.0

ICD-10: L56.0

Inadvertent contact with or therapeutic application of a photosensitizer, followed by UVA irradiation (practically all topical photosensitizers have an action spectrum in the UVA range).

Inadvertent contact with or therapeutic application of a photosensitizer, followed by UVA irradiation (practically all topical photosensitizers have an action spectrum in the UVA range). The most common topical phototoxic agents are Rose Bengal used for ophthalmologic examination, the dye fluorescein and furocoumarins that occur in plants (compositae spp and umbiliforme spp), vegetables and fruits (lime, lemon celery, parsley), in perfumes and cosmetics (oil of bergamot), and drugs used for topical photochemotherapy (psoralens). The most common route of contact is either therapeutic or occupational exposure.

The most common topical phototoxic agents are Rose Bengal used for ophthalmologic examination, the dye fluorescein and furocoumarins that occur in plants (compositae spp and umbiliforme spp), vegetables and fruits (lime, lemon celery, parsley), in perfumes and cosmetics (oil of bergamot), and drugs used for topical photochemotherapy (psoralens). The most common route of contact is either therapeutic or occupational exposure. Clinical presentation is like acute irritant contact dermatitis (see

Clinical presentation is like acute irritant contact dermatitis (see  Symptoms are smarting, stinging, and burning rather than itching.

Symptoms are smarting, stinging, and burning rather than itching. Healing usually results in pronounced pigmentation (see

Healing usually results in pronounced pigmentation (see  ICD-10: L56.2

ICD-10: L56.2

An inflammation of the skin caused by contact with certain plants during recreational or occupational exposure to sunlight (plant + light = dermatitis).

An inflammation of the skin caused by contact with certain plants during recreational or occupational exposure to sunlight (plant + light = dermatitis). The inflammatory response is a phototoxic reaction to photosensitizing chemicals in several plant families.

The inflammatory response is a phototoxic reaction to photosensitizing chemicals in several plant families. Common types of PPD are due to exposure to limes, celery, and meadow grass.

Common types of PPD are due to exposure to limes, celery, and meadow grass. Synonyms: Berloque dermatitis, lime dermatitis.

Synonyms: Berloque dermatitis, lime dermatitis. ICD-10: L56.1

ICD-10: L56.1

This results from interaction of a photoallergen and UVA radiation.

This results from interaction of a photoallergen and UVA radiation. In sensitized individuals, exposure to a photoallergen and sunlight results in a pruritic eczematous eruption confined to exposed sites and clinically indistinguishable from allergic contact dermatitis.

In sensitized individuals, exposure to a photoallergen and sunlight results in a pruritic eczematous eruption confined to exposed sites and clinically indistinguishable from allergic contact dermatitis. In most patients, the eliciting drug/chemical has been applied topically, but systemic elicitation also occurs.

In most patients, the eliciting drug/chemical has been applied topically, but systemic elicitation also occurs.