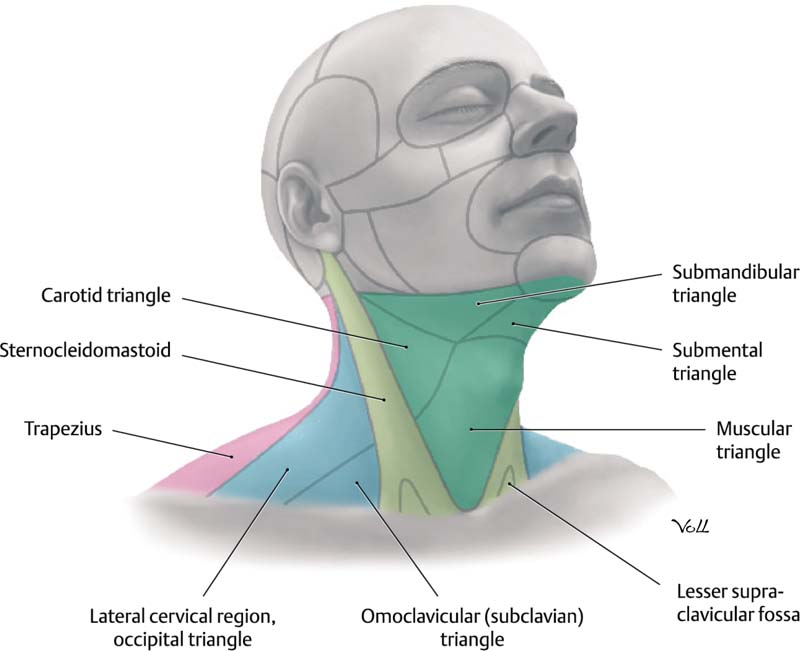

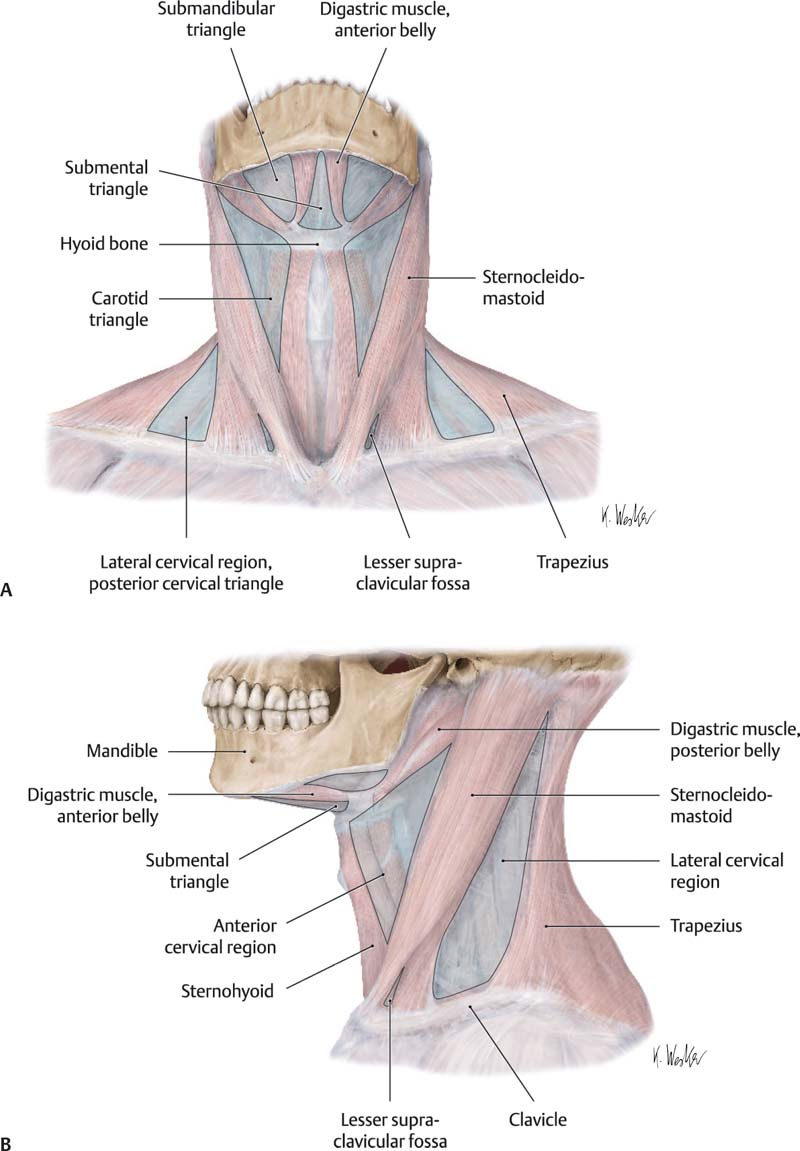

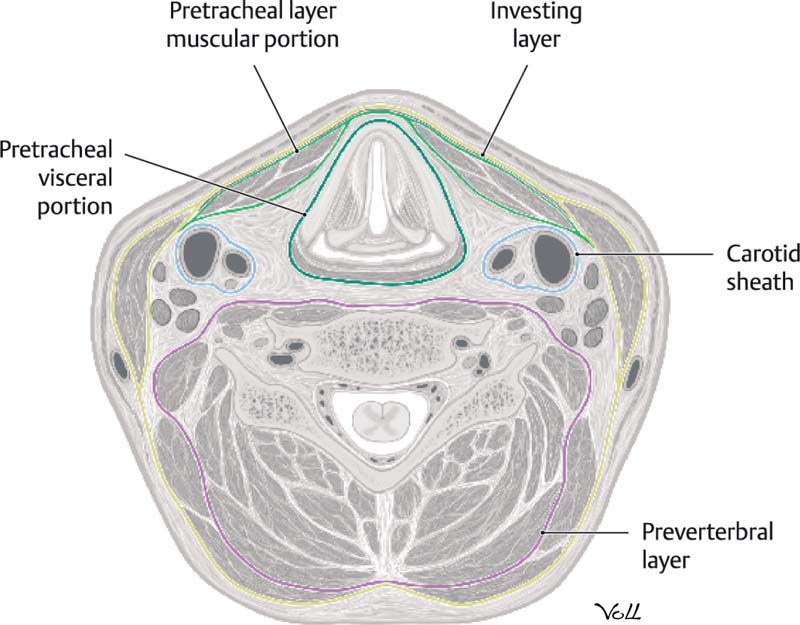

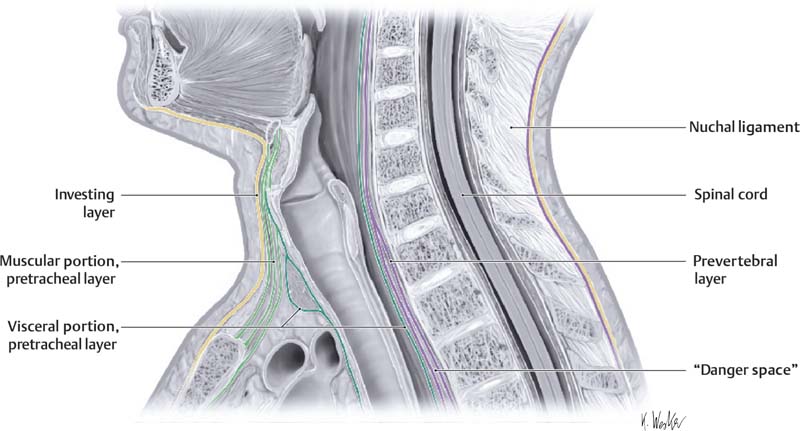

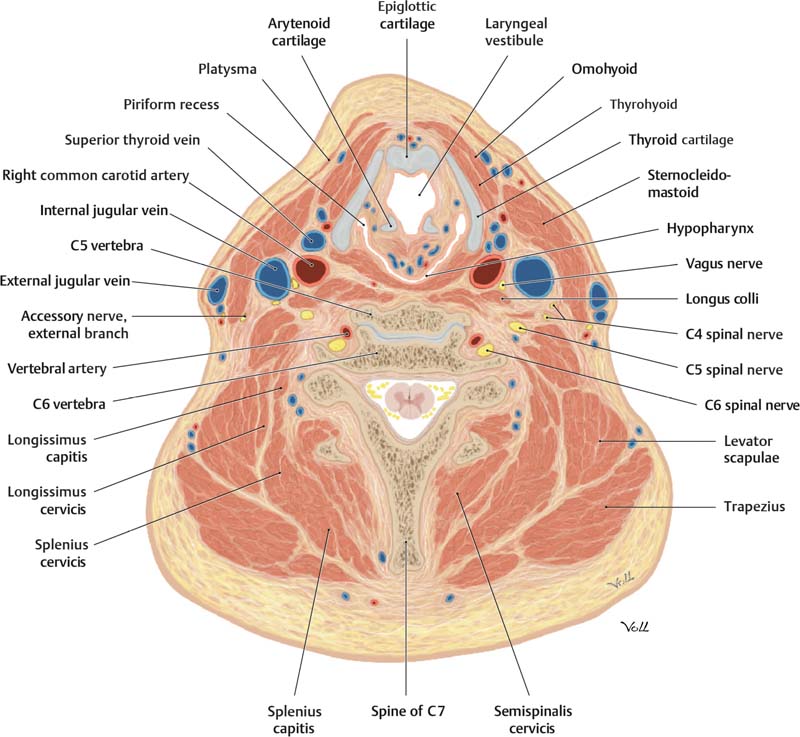

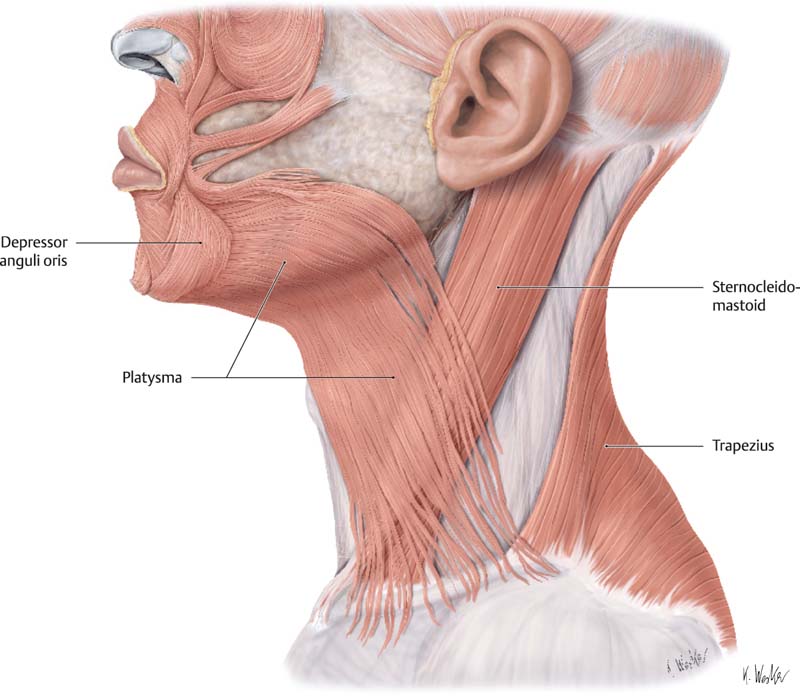

1 A well-contoured neck is a hallmark of youth, health, and attractiveness. The neck is a highly complex anatomical structure, and a complete working knowledge of the anatomy of the neck is therefore essential for any surgeon who seeks to rejuvenate this area of the body. In this chapter we will address the anatomy and physiology of the neck. The superior limit of the neck is the hard palate. Inferiorly the neck is demarcated by the sternum and clavicles. It also has both anterior and posterior compartments delineated by the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle. The anterior compartment is bordered by the mandible superiorly, the SCM muscle posteriorly, and the midline anteriorly (Fig. 1.1). The hyoid bone divides the anterior compartment of the neck into the suprahyoid and infrahyoid spaces. The suprahyoid neck is divided into the submental and submandibular spaces by the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle. The posterior compartment of the neck is divided by the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle (Figs. 1.2A,B). Fig. 1.1 Right lateral view of the neck. For descriptive purposes the anterior and lateral neck are divided into two triangles, which share the SCM muscle as a boundary. Each triangle is further divided into smaller triangles. (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Neck and Internal Organs, © Thieme 2006, Illustration by Markus Voll.) Fig. 1.2 (A) Anterior view of the neck. (B) Left lateral view of the neck. (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Neck and Internal Organs, © Thieme 2006, Illustration by Karl Wesker.) The neck is divided into layers and potential spaces by the cervical fascia. The cervical fascia is composed of fibrous connective tissue that envelops muscles, nerves, and blood vessels as well as the thyroid gland, trachea, and esophagus. The two layers of cervical fascia are the superficial and the deep layers. The superficial layer of the cervical fascia is located deep to the dermis yet superficial to the platysma muscle. It ensheathes the platysma and is continuous with the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). The space between the superficial cervical fascia and the deep cervical fascia contains adipose tissue, the external and anterior jugular veins, sensory nerves, and facial motor nerves (Fig. 1.3). Fig. 1.3 Relationships of the deep fascia of the neck (transverse section at the level of the C5 vertebra). (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Neck and Internal Organs, © Thieme 2006, Illustration by Markus Voll.) The deep cervical fascia is subdivided into superficial, middle, and deep layers. The superficial layer of this fascia can be remembered with the “rule of twos.” It envelops two muscles (trapezius and SCM), two glands (submandibular and parotid), and forms two neck spaces (space of the posterior triangle and the suprasternal space of Burns in the anterior midline). The intermediate layer of the deep cervical fascia is also called the pretracheal fascia. It envelops the strap muscles, thyroid gland, trachea, and esophagus. The deep layer of the deep cervical fascia is the posterior prevertebral layer, which envelops the scalene muscles and the vertebrae (Fig. 1.4).1 The fascial layers divide the neck into spaces. The suprahyoid neck is divided into the peritonsillar, submandibular, sublingual, and lateral pharyngargeal spaces. The infrahyoid neck is divided into the anterior visceral space and the retropharyngeal, prevertebral, and carotid-sheath spaces (Fig. 1.5).2,3 Fig. 1.4 Fascial relationships of the neck (left lateral view). (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Neck and Internal Organs, © Thieme 2006, Illustration by Karl Wesker.) Fig. 1.5 Transverse cross-section of the neck at the level of the C5 vertebral body. (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Neck and Internal Organs, © Thieme 2006, Illustration by Markus Voll.) Skin and subcutaneous tissue overlie the platysma muscle in the neck. Most of the anterior neck has a similar distribution of subcutaneous fat; however, there is slightly more fat in the submental area. This submental fat occupies the space between the platysma and the underlying mylohyoid muscle, and this may contribute to the appearance of submental fullness and laxity.4 The appearance of aged skin develops in the same manner, whether on the face or on other regions of the body, from atrophic thinning of the skin and loss of collagen and elastin, with the resultant appearance of skin laxity and rhytids. The combination of thin skin tissue and loss of the mechanical integrity of the skin with long-term kinetic activity of the platysma muscle may deepen horizontal rhytids in the neck.5 The platysma is a flat, thin muscle located in the anterolateral aspect of the neck. The thickness of the platysma varies, and it tends to be thicker in men than in women. The platysma is innervated by the cervical branch of the facial nerve, a branch deep to the platysma, and assists the depressor anguli oris in depressing the lower lip. The superior insertion of the platysma is into the chin around the commissure of the mouth and in the anterior third of the oblique line of the mandible. Its inferior attachment is in the subcutaneous tissues of the subclavicular and acromial regions (Fig. 1.6).6 As one proceeds superiorly from the neck to the inferior border of the mandible, there is a transition from the platysma to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), which covers the face. In the 1970s it was determined that the SMAS is a continuation of the platysma muscle.7 The SMAS and platysma divide the subcutaneous fat of the neck and face into two distinct layers. The subplatysmal plane contains a fat layer, the cervical branches of the facial nerve, the submandibular gland, the tail of the parotid gland, and the external jugular vein. In the submental area and suprahyoid region, thick subcutaneous tissue overlies the platysma muscle. Inferiorly, the subcutaneous tissue becomes less thick and the plastysma lies in close proximity to the skin. Fig. 1.6 Cutaneous muscles of the neck. The superior and inferior attachments of the platysma muscle can be appreciated in this left lateral view. (From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Neck and Internal Organs, © Thieme 2006, Illustration by Karl Wesker.) Posteriorly and superiorly, the fascicles of the platysma muscle form a lazy “S.” These fascicles always pass posterior to the angle of the mandible. Importantly, the medial platysmal fibers have the highest degree of variability. Medially, the fibers of the platysma interdigitate at the level of the thyroid cartilage, forming an inverted “V.”6,8 The apex of this “V” can be at the level of the chin or slightly below this, at the level of the thyroid cartilage. Because of this, the submental area may or may not be covered by the fibers of the platysma muscle.8 Flaccidity of the superolateral fibers of the platysma may be a contributing factor to chin droop and jowling. Cadaver studies by de Castro revealed three different patterns in which the fibers of the platysma interdigitate in the submental area.8 The most common such pattern is designated type I (seen in 75% of cadavers), in which the medial fibers of the platysma interlace with those of the muscle on the opposite side at a distance of 1 to 2 cm below the chin. The fibers remain separate in the suprahyoid region. In the type II pattern (seen in 15 to 17% of cadavers), the fibers of the platysma begin to interdigitate at a lower level than in the type I pattern. In this type of interdigitation the area from the thyroid to the submental region is covered by a continuous sheet of muscle. In the type III pattern of interdigitation (seen in 10% of cadavers), the medial fibers of the platysma remain entirely separate from and do not interlace with the fibers of the contralateral platysma. Instead, they insert directly into the cutaneous muscles of the chin.8Aponeurotic condensations of connective tissue attach the platysma to the dermis. Posteriorly the platysma gives rise to fascial condensations that attach to the overlying skin. These fibrous condensations are the posterior auricular ligaments on either side of the face, which act to anchor the platysma to the dermis of the infra-auricular region. Cutaneous branches of the greater auricular nerve can be seen coursing on or within this fascial condensation. Branches of the great auricular nerve pierce the posterior auricular ligament to provide sensation to the area of the parotid gland. This fascial condensation may alert the surgeon to the presence of the greater auricular nerve in this vicinity.9 The anterior platysma forms bands of fascial tissue that connect with the skin of the middle and anterior cheek. These bands pass obliquely and anteriorly from the platysma to the dermis, forming what are called the anterior platysma–cutaneous ligaments. Dissection along the fascial band on either side of the neck has the potential to divert the plane of dissection toward the dermis, leading the surgeon to inadvertently thin the elevated skin flap (consisting of skin and sub-cutaneous tissue that lies superficial to the SMAS) created by the dissection. To prevent this, the surgeon can transect the anterior platysma~cutaneous ligament before the dissection plane is identified. The ligament may be associated with a fibrous fascial investment of the platysma and extensions to the skin of the cheek. This musculoaponeurotic layer can improve the degree of the lift and overall appearance. On the other hand, it can also provide points of dimpling that may require separation of an SMAS flap from the dermis.9

The Anatomy and Physiology of the Neck

Boundaries of the Neck

Fascial Layers

Skin

Platysma

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree