Forehead

BIOANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

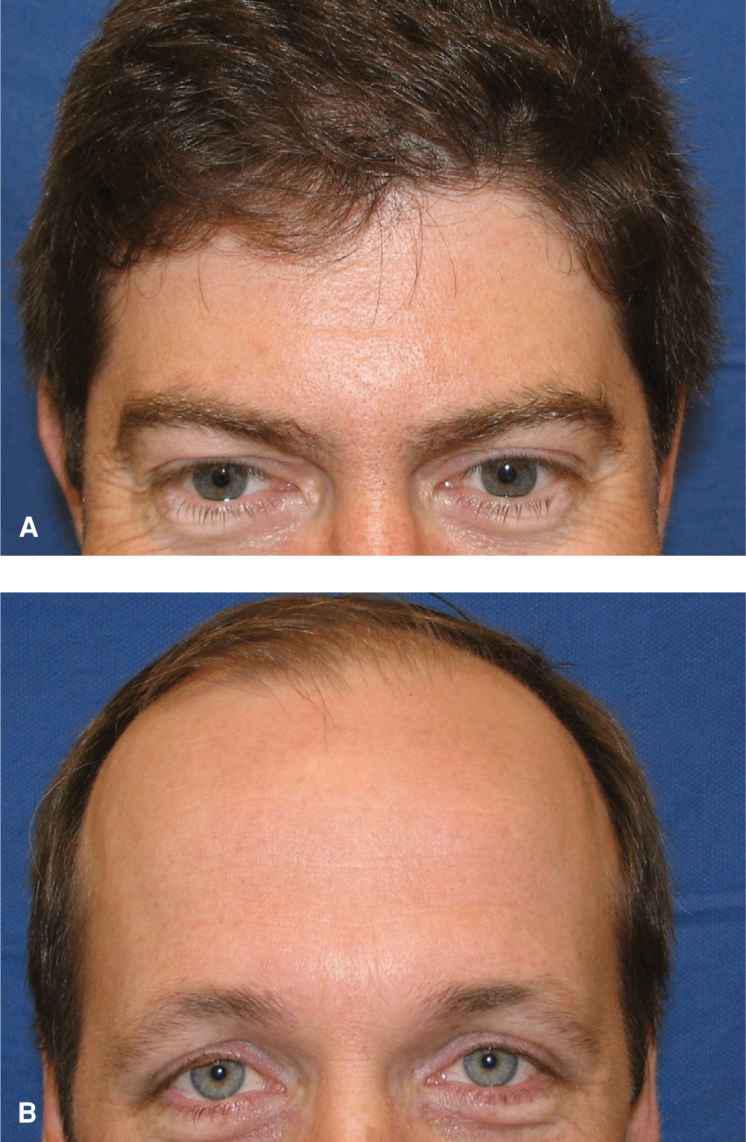

The forehead extends from the hairline superiorly to the eyebrows inferiorly and merges into the temple laterally at the temporal fossa. The skin of the forehead is moderately sebaceous and varies considerably in mobility from one individual to another. In youth, the forehead is smooth. With age, a series of dynamic horizontal rhytides appears. There is considerable variation in the vertical height of the forehead, with some individuals having a very low hairline and others having a higher hairline and a more prominent forehead (Fig. 12.1).

Figure 12.1 Natural variation in the height of the forehead. (A) Low hairline and short forehead. (B) High hairline and broad forehead

The forehead is prominent in the perception of appearance. Repairs that result in lines are generally well tolerated, whereas skin grafts are best avoided when feasible. Eyebrow symmetry should be maintained, and this may mean the placement of a vertical rather than a horizontal incision line. While historically the closure of wounds with horizontal linear repairs was favored, for a number of reasons discussed later, vertical incisions are often preferable.

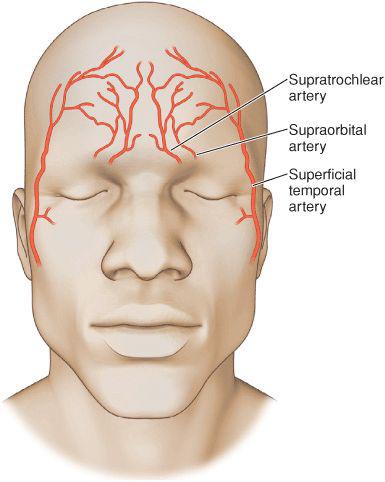

The forehead has a rich vascular supply (Fig. 12.2). From medial to lateral, the forehead is supplied by the dorsal nasal vessels, the supratrochlear system, and the supraorbital artery, all of which are branches of the internal carotid artery. Laterally, the blood supply is from the frontal branches of the superficial temporal artery, itself a branch of the external carotid. The lateral and inferior blood supply anastomoses broadly with vessels from the scalp at the hairline. The main vessels of the medial forehead emerge from bony foramina and ascend just over muscle for a short distance before ascending into the adipose and gradually becoming more superficial as they branch extensively onto the mid and upper forehead.

Figure 12.2 Vascular supply of the forehead. The medial forehead is mainly supplied by the supratrochlear and supraorbital plexi, whereas the lateral forehead is supplied by branches from the superficial temporal system. There is a wide anastomosis of the arterial supply of the forehead

The sensory innervation of the forehead parallels that of the vascular supply, with rich innervation from the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves. The nerves run just above the frontalis until they are midway up the forehead, at which point their branches ascend to a more superficial level (Fig. 12.3). Transection of the main nerve branches may lead to temporary or permanent anesthesia and may also result in piercing postoperative pain and long-standing neuralgia. Motor innervation of the forehead comes from the frontal branch of the temporal nerve. This nerve lies deep and lateral on the forehead, running in the muscular fascia. Injury to this nerve, which is far more common when working on the temple, results in ipsilateral forehead paralysis.

Figure 12.3 The supraorbital nerve is visualized during a linear repair on the forehead

The forehead has only a thin subcutaneous layer. In youth, adipose is minimal and the dermis is firmly attached to the frontalis muscle by numerous fibrous septae. In later life, the adipose layer is often well formed, and a more defined subcutaneous plane may exist. The frontalis is covered superficially by a minimal layer of supramuscular fascia. Beneath this are the bellies of the frontalis muscles that extend from the temporal fossa laterally to the supra-trochelar region medially. Right at the midline, the musculature is absent. Deep to the frontalis is the inelastic fibrous extension of the galea aponeurotica. In general, two undermining planes can be delineated on the forehead. The first is above frontalis muscle. Here, meticulous flap elevation avoids the transaction of larger arteries and neural structures. Substantial flap motion may be achieved by undermining at this level, but it is not an easy plane to master. Undermining may also be achieved underneath the deep fascia. This is an easy, bloodless plane to undermine but has two disadvantages. First, the amount of laxity achieved by undermining is limited. Second, if horizontal incisions are made, they cut right through the large vessels and nerves with resultant consequences. The amount of mobility afforded by a given scalp is extremely variable. Some individuals have a very mobile scalp, whereas others have a scalp that feels to be as tight as a drum.

LINEAR REPAIRS

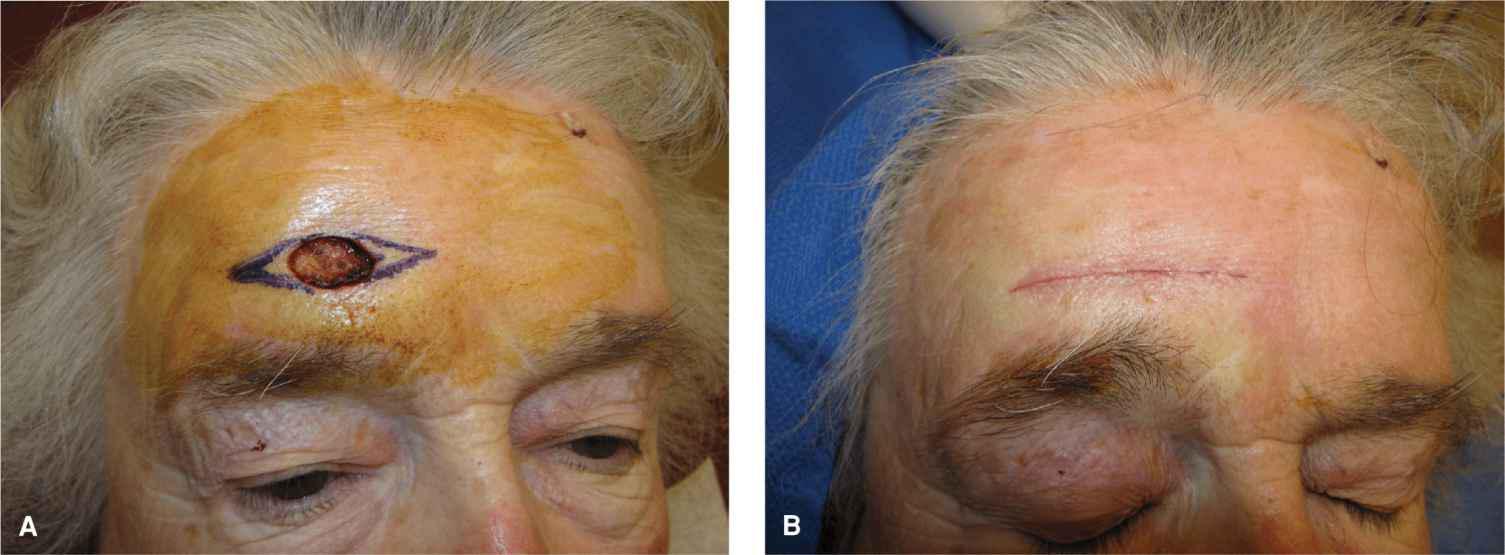

The majority of forehead wounds can be repaired linearly, and in most cases, the best repairs are vertical rather than horizontal.1 Small wounds may be repaired horizontally (Fig. 12.4), but horizontal closure of larger wounds creates eyebrow asymmetry and risks long-standing sensory disruption. Linear forehead repairs may be performed either above frontalis or beneath the deep galeal fascia. By orienting the repair in a vertical direction, disruption of the neurovascular bundles is minimized. Properly planned and executed, vertical linear repairs on the forehead can be highly aesthetic (Fig. 12.5). When feasible, the fascia or muscle should be reapproximated, as this may diminish the depth and/or inversion of the scar line. If a broad wound is close linearly by only approximating dermis to dermis, a depressed coup de sabre appearance may result. A key point to remember in repairing the forehead linearly is that it is a convex structure, and this accentuates the formation of dog-ears or standing tissue cones. For that reason, longer repairs are needed and a standard length-to-width ratio may require modification. In some cases, it is necessary to turn the repair into an A-to-T or an M-plasty to get one end of the incision to lie flat.2

Figure 12.4 Horizontal repair on the forehead. (A) A horizontally oriented oval wound with a planned linear repair. The repair is long in order to compensate for the curvature of the forehead and to prevent the formation of standing tissue cones medially and laterally. (B) Immediate repair. Because the height of the wound is limited, pull on the brow is not appreciated and relative eyebrow symmetry will be maintained

Figure 12.5 Vertical repair on the forehead. (A) Wound and planned repair. (B) Immediate repair. The position of the eyebrow is unaffected. The repair is long to avoid the formation of standing tissue cones. (C) Closure at 1 year demonstrating cosmesis

A vertical line on the forehead may heal almost invisibly, or more commonly, it may be a fine white line. Usually it is an excellent repair. Some authors feel that breaking the repair up into multiple Z-plasties can accomplish two improvements, namely minimizing scar inversion and obscuring the sharp line of a single repair.3 Both of these are true in given instances and there is some utility to this technique. A poor outcome from a single linear repair is a visible indented line, whereas a poor outcome from a Z-plasty is extremely aesthetically displeasing. For that reason, and to avoid unnecessary complexity, it is usually preferable to create a linear repair and perform revisions if needed, rather than starting with multiple Z-plasties.

MEDIAL FOREHEAD

Advancement

Moderate-to-large wounds of the medial forehead can be repaired with advancement flaps, which displace dogears away from eyebrow and tap into some laxity from the medial forehead and glabella. Textbooks are replete with diagrams showing standard box-shaped unilateral advancements and H-shaped bilateral advancements. In practice, such flaps have limited use. When elevated above muscle, they have a tenuous vascular supply, they recruit little laxity, and they create complex incision lines. In most cases, a Burrow’s wedge type of repair is preferred. In this case, the repair is linear on the forehead, jogs medially over the brow, and then removes a triangular tissue cone into the glabella (Fig. 12.6). In many cases, the flap can be elevated and closed above muscle, thus avoiding neurovascular structures. While the eyebrow may be displaced medially by this repair, most motion occurs from medial to lateral, and as such both eyebrows tend to move inward and remain reasonably symmetric. By virtue of the forehead portion of the wound being a vertical linear closure, the sensory disruption of the repair is minimized. For wounds high on the forehead, advancement does not hide incision lines. Advancement does allow for a portion of the repair to be performed on the midline where there are fewer neurovascular structures and where deep plane undermining is easier (Fig. 12.7).

Figure 12.6 Advancement flap for the medial forehead. (A) Wound of the medial brow and planned advancement. The horizontal limb of the flap displaces the repair away from the medial brow. (B) Immediate repair. (C) Repair at 6 months

Figure 12.7 Moderate wound of the medial forehead repaired with an advancement flap. (A) Wound and planned repair. The repair breaks the line up and diminishes the chance for scar line inversion. In addition, but moving the lower portion of the repair to the midline, a deeper plane of undermining may be undertaken without disrupting the supratrochlear neural and vascular systems. (B) Immediate repair. A small dog-ear has been removed laterally and a diminutive portion of the wound is allowed to heal secondarily. (C) Repair at 4 weeks

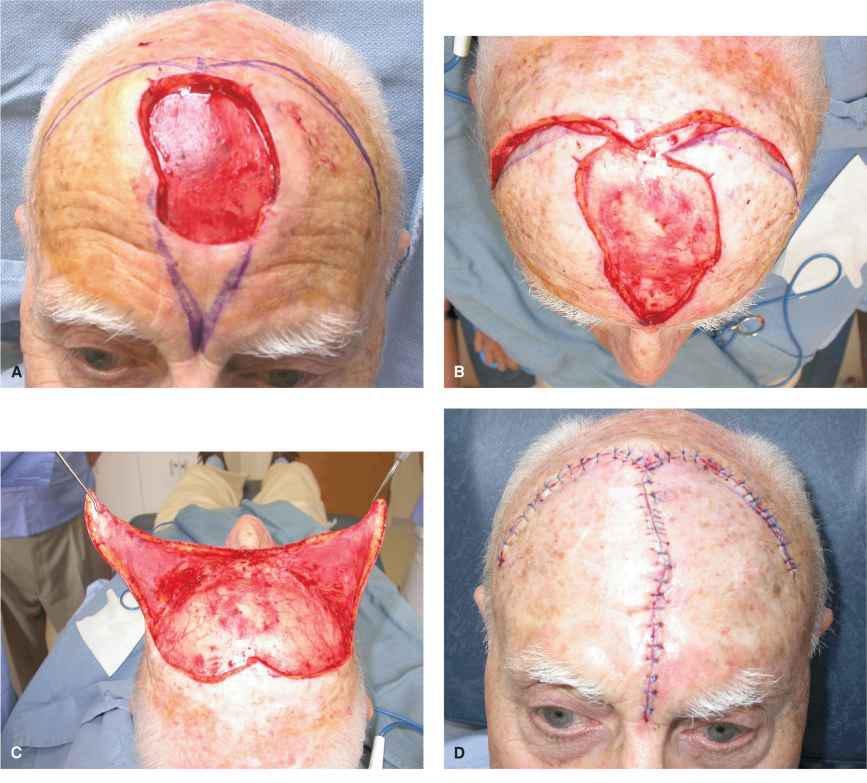

Rotation Flaps

Large wounds of the upper medial forehead may be challenging to close. Laxity in this area is lacking in many patients, and the achievement of adequate side-to-side motion may be a challenge. When a large, deep wound exists, a broad bilateral rotation flap can be utilized to achieve closure4,5 (Fig. 12.8). To affect this repair, a long triangular standing tissue cone is dropped from the wound and a broad coronal incision line is created along the hairline. In some cases, a unilateral rotation is suitable, but a bilateral rotation may be needed. This repair is done at a deep plane beneath fascia and is undermined all the way down to the supraorbital region. Substantial rotational motion is achieved along the primary motion of the flap. The secondary defect may be a bit more challenging to repair, as the scalp remains relatively immobile. One downside of this repair is that prolonged, if not permanent, anesthesia of the anterior scalp will result.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree