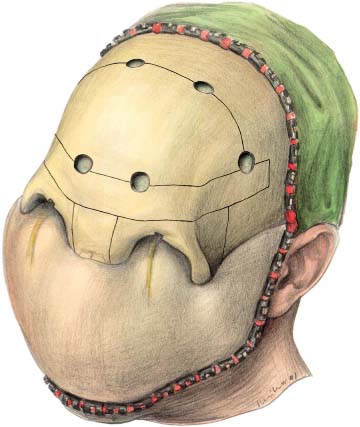

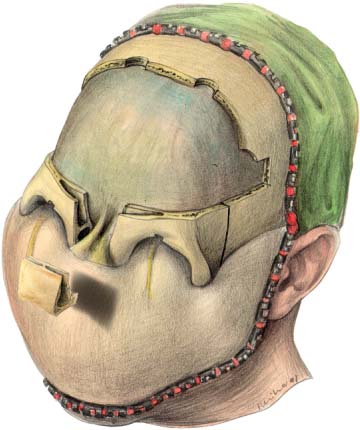

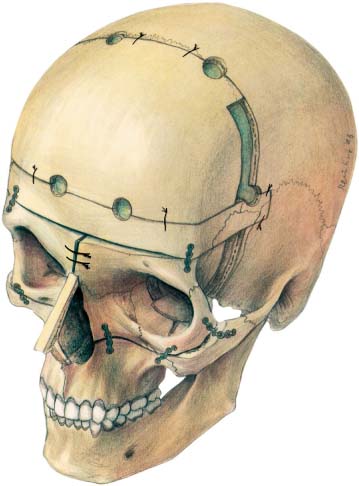

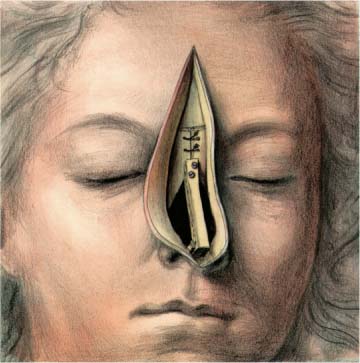

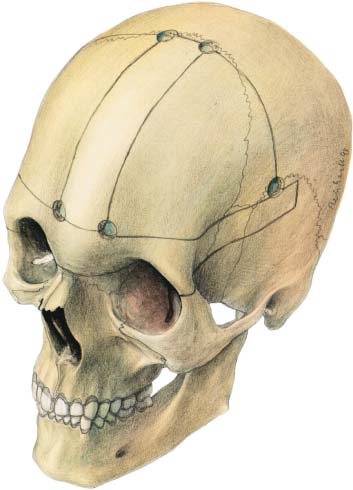

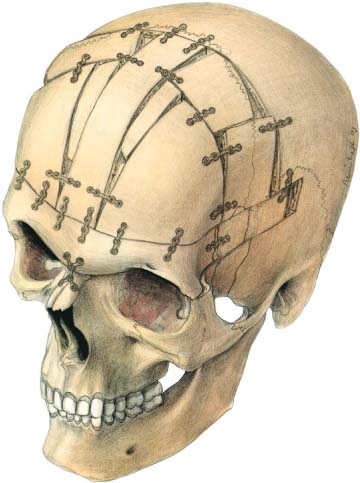

26 Craniofacial Surgery The surgical correction of hypertelorism, perhaps the most breathtaking procedure seen in modern surgery, was developed by Paul Tessier (1967, 1972). In principle, the operation consists of the cutting out of the orbits from the anterior and medial cranial fossae and medially rotating the upper midface with the orbital contents. A coronal and a median transnasal and transfrontal approach is used to expose the anterior half of the skull, the supraorbital rims, the whole nasal skeleton, the lateral orbital rims and walls, the zygomatic complex, and the infraorbital area as far as possible from the temporal access. Often a transconjunctival approach (Sailer, 1977, 1978) is used for better control of the median and lower orbital wall. The inner canthal ligaments are exposed and preserved and the periorbital tissues carefully stripped off the bone on all four sides of the orbit. The infraorbital area and the canine fossa is approached via an upper vestibular incision. With the aid of preoperative planning using computed tomographic scans, three-dimensional imaging, stereo-lithography models, and the necessary clinical data (Sailer and Grätz, 1995), the craniotomy and osteotomy lines are outlined with a Toller burr (Fig. 26.1). A simulation of the operation with the aid of a stereo-lithography model should always be performed. After the craniotomy, a supraorbital bandeau is removed and the anterior skull base, the crista galli, and the anterior olfac-tory nerve filaments are exposed. First the interorbital bone and most of the nasal skeleton are removed (Fig. 26.2), then gradually the bone around the olfactory nerve filaments (using magnifying loops) and the inter-orbital ethmoidal cells are removed (Sailer and Landolt, 1987a, b). Fig. 26.1 Hypertelorism procedure. The osteotomy lines and burr holes are outlined. Fig. 26.2 After craniotomy and removal of the frontal bone the interorbital bone structures including the nasal ones are removed and the olfactory filaments carefully preserved when removing the anterior part of the cribriform plate. 132 26 Craniofacial Surgery Fig. 26.3 After median rotation of the orbits with the aid of two wires in the glabela region the orbital structures are fixed by microplates and titanium wires and all defects bridged by lyo-cartilage and lyobone. A piece of calvarial bone is taken (left side) for reconstruction of the nose. Fig. 26.4 Finally, the nasal frame work is reconstructed using a piece of calvarial bone which is fixed by mini screws to the glabela area. The surplus skin in the nasal and frontal area is removed (Rosalba Carriera, Self-portrait, ca. 1710/1720, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin). The osteotomies through all orbital walls are performed behind the greatest diameter of the orbital contents; sometimes it is necessary to connect the osteotomies of the median orbital wall and the orbital floor via a transconjunctival approach (Sailer, 1978). The zygomatic complex is divided transversely, in an infraorbital direction (Fig. 26.3). The zygomatic osteotomy is completed below the infraorbital foramen into the piriform aperture beneath the lower turbinate, using an intraoral upper vestibular approach. A triangular piece of bone above this osteotomy is removed from both sides of the piriform aperture. Both orbits are gently mobilized by finger pressure and by the use of broad chisels placed into the lateral orbital osteotomy. Now, >two wires are placed within the glabela region and both orbits gently pulled and pressed together. The fixation of the supraorbital bandeau to the orbits and the calvaria is done mostly with titanium wires. A few mini-plates can be used, preferably at the lateral orbital rim, in the zygomatic area for fixation of the lyophilized bone grafts (Sailer, 1992), and in the infraorbital region (Fig. 26.4). In children we prefer to use resorbable plates and screws, because contour corrections are necessary later, which would require removal of often-osseointegrated titanium plates, causing loss of bone. The defects in the cranial base and orbital walls are bridged by lyophilized cartilage slices (Sailer, 1992). The nasal frame work is reconstructed by an L-shaped strut of calvarial bone, which is fixed firmly to the glabela region by two mini-screws (see Fig. 26.4). At the end of surgery the surplus skin in the frontal and nasal area is excised along the median transnasal–trans-frontal incision. The correction of the fronto-orbital area in a syndromal or nonsyndromal craniosynostosis condition is based on the work of Tessier (1967) and Marchac et al. (1974). The most common fronto-orbital corrections have to be performed in scaphocephaly, frontal plagiocephaly, trigonocephaly, and brachycephaly. The principles of correction of occipital scaphocephaly and occipital plagiocephaly (Sailer and Landolt, 1991) are described later. Craniosynostosis corrections are usually performed during the first years of life when skull growth is fast. Clinical experience has shown that metallic plates on outer skull surfaces disappear in the intracranial direction by outer bone apposition and inner calvarial resorption. Finally, the plates and screws are lying on top of the dura and screws can penetrate into it. For this reason metallic plates on the growing skull have to be removed approximately 6 months after surgery—or resorbable plates and screws should be used. From our point of view, titanium miniplates should always be removed (Rosenberg et al., 1993) because a metallosis is possible. Fig. 26.5 Fronto-orbital correction in trigonocephaly (as modified by Sailer). The osteotomies are arranged so that the sinus system is protected by a strip of bone in the median skull area.

Hypertelorism

Correction of Craniosynostosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree