Cutaneous Adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is a malignant lymphoproliferative disease associated with a retrovirus infection caused by the human T-cell lymphotropic virus I (HTLV-I). The disease is endemic in the south of Japan and in the Caribbean Islands and is rare in other regions, but reports on its occurrence have come from many different countries besides the endemic ones. Cutaneous manifestations and histopathologic features are identical to those of mycosis fungoides, so demonstration of retroviral infection is mandatory for the diagnosis. Cutaneous ATLL is included as a specific entity in the World Health Organization (WHO)–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) classification of primary cutaneous lymphomas [1]. Four variants of ATLL are recognized in the WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [2]: acute leukemic, chronic leukemic, lymphomatous, and smoldering. Although skin manifestations are usually considered as a smoldering form of the disease, it has been suggested that patients with purely cutaneous lesions may have a better prognosis and should be classified separately from those with smoldering ATLL [3, 3a].

Clinical Features

Patients are adults or elderly with a prevalence of males. Adolescents may be affected rarely [4]. Specific skin manifestations can be observed in about half of the patients, especially those presenting with indolent forms of the disease [5–7]. Primary cutaneous involvement may also be seen [7]. Anti-HTLV-I antibodies can be demonstrated in the serum of affected individuals. Onset of ATLL has been observed in three patients who received organs from an HTLV-1+ donor [8].

The clinical presentation of the cutaneous form is indistinguishable from that of mycosis fungoides. Cutaneous lesions are localized or generalized macules, papules, patches, plaques, and tumors (Figs 9.1 to 9.4) [5, 6, 9, 10]. Erythroderma may also develop. Rarely the disease may present with large solitary nodules [11]. A leukemic blood picture and involvement of the bone marrow are found in more than half of the patients. Spontaneous regression of skin lesions has been observed rarely [12].

Patients with ATLL have an impaired immune response and may develop atypical cutaneous mycotic infections characterized by little or no inflammation, due to downmodulation of skin immunity against dermatophytes.

Histopathology, Immunophenotype, and Molecular Genetics

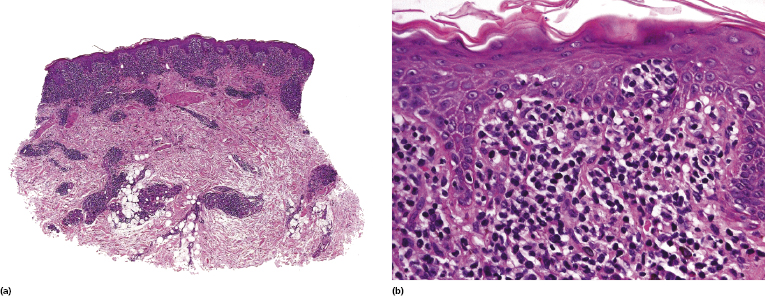

Histology shows an infiltrate of small/medium or medium/large pleomorphic lymphocytes with prominent epidermotropism (Fig. 9.5). The histopathologic picture is often indistinguishable from that of mycosis fungoides, and rarely follicular mucinosis may be observed within the skin infiltrates as well [13]. Variants of ATLL with angiocentricity and/or angiodestruction or with bullous lesions have been observed [14, 15].

Immunohistology usually reveals a T-helper (CD3+, CD4+, CD8−) phenotype, but some cases may be CD4−/CD8+ or CD4+/CD8+. The tumor cells are positive for CD25 and frequently for the T regulatory (Treg) molecule forkhead box protein P3 (FOX-P3), thus possibly deriving from Treg lymphocytes [16–18]. Although FOX-P3 expression by neoplastic cells is observed only in a minority of cases of mycosis fungoides [19], positivity or negativity for this marker cannot be considered as reliable differential diagnostic clues. Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) is strongly expressed by neoplastic cells [19a].

Molecular analyses show a monoclonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor (TCR) genes, as well as the presence of the integrated genome of HTLV-I [20]. In this context, it should be underlined that, prompted by the clinicopathologic similarities to ATLL, several investigators have looked for the presence of HTLV-I DNA in cases of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. There is no convincing evidence of the involvement of HTLV-I in these diseases, thus demonstration of monoclonal integration of HTLV-I DNA in neoplastic cells may be used as a reliable means to distinguish ATLL from mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome.

Treatment and Prognosis

The prognosis of ATLL is generally poor, but indolent variants have been described. The smoldering type seems to have a better prognosis [21]. The type of skin eruption may be an independent prognostic factor, as patients presenting with patches and plaques have a better prognosis than those showing erythroderma, multipapular, nodulo-tumoral, or purpuric lesions [22].

The treatment of choice for ATLL is usually systemic chemotherapy, eventually followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Cases with an indolent behavior and restricted to the skin may be managed with less aggressive therapeutic options such as psoralen and UV-A (PUVA) or combination schemes [5, 6, 23, 24]. The Japanese Skin Cancer Society–Lymphoma Study Group has issued recommendations for treatment of cases with disease limited to the skin [25]. Besides PUVA, other useful options include radiation therapy, retinoids, interferon, and single-agent chemotherapy [25].

Full access? Get Clinical Tree