CHAPTER 23 Vulvar Neoplasms and Cysts

Epidermoid cysts

Epidermoid cysts form by one of two mechanisms: traumatic inclusion of epithelial fragments or blockage of a pilosebaceous unit. Inclusion-type cysts generally arise during surgical procedures in which fragments of epithelium are unwittingly implanted under the epithelial surface. There, these epithelial fragments round up and the keratinocytes begin making keratin which is released into a central cavity. This mechanism accounts for essentially all the epidermoid cysts encountered within the vagina and most of these occurring in the vulvar vestibule. On the other hand, epidermoid cysts found lateral to Hart’s line (on the labia minora, on the labia majora, and on other hair-bearing portions of the anogenital region) arise from pilosebaceous units. Those with a visible opening (a “blackhead” or tiny pit) on the surface develop due to blockage of the follicular outlet with subsequent production of keratin within the closed space of the follicle. Those without a visible opening are more likely to have developed from a remnant of an anatomically malformed follicle that lacks an opening to the surface.

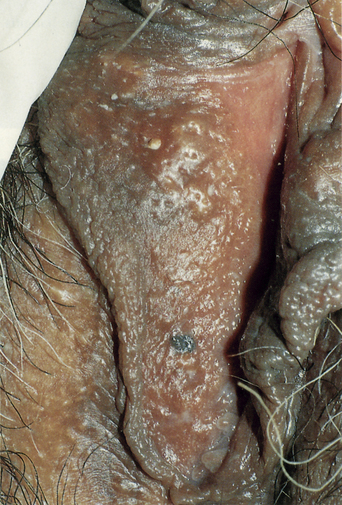

The size of epidermoid cysts varies from 1 to 2 mm (so-called milia) to several centimeters (Figures 23.1 and 23.2). One or several cysts may be present. Multiple, grouped cysts are particularly common on the labia majora (Figure 23.3). Cysts arising close to the surface appear white or yellow-white due to the visibility of the keratin contents that can be seen through stretched overlying epithelium (Figure 23.4). Deeper lesions are skin-colored. The sharp boundary and firmness of the cyst wall can often be appreciated on palpation. Epidermoid cysts, unless inflamed, are asymptomatic.

Figure 23.2 Vestigial follicles on the labia minora allow for folliculitis and epidermal cysts in some patients.

(Reproduced from P. J. Lynch and L. Edwards Genital Dermatology (Fig. 10-6), New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994.)

Bartholin cysts

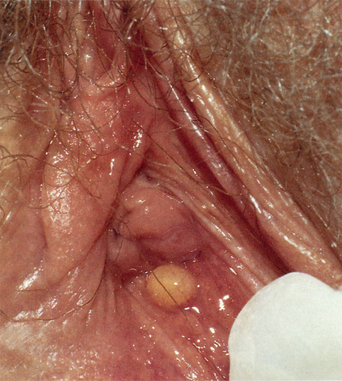

Bartholin glands are situated bilaterally, posterior and lateral to the vagina. The ducts from these glands open into the vestibule at approximately 5:00 and 7:00 in relation to the vaginal introitus. These glands secrete a mucus-like material that plays a role in lubrication during sexual activity. Cysts form within the ducts of Bartholin glands, presumably as a result of ductal obstruction. Small cysts (< 1 cm) are extremely common. They are painless and may be palpable but may not be visible. Larger cysts (1–5 cm) may be associated with discomfort and may interfere with penile intromission. A characteristic diagnostic feature is the fact that the labium minus crosses over the midline of the cyst (Figure 23.5).

Bartholin cysts may become inflamed and painful. The historical presumption was that the inflammation was due to infection, especially that of gonorrhea. Today it seems likely that, in most cases, the thinned wall of an enlarging cyst ruptures and releases cyst contents into the surrounding tissue, thereby causing a foreign-body inflammatory reaction. Rarely, Bartholin cysts develop in postmenopausal women as a result of malignant transformation1. Immediate treatment is that of incision and drainage.

Asymptomatic cysts should be left untreated. Inflamed cysts can be incised and drained, with a sample of purulent material being sent for bacterial culture. Empirical antibiotic therapy may be carried out until the results of the cultures are known. Incised cysts frequently reform, which may then require more extensive surgery such as marsupialization or incision with insertion of a Word catheter1.

Cysts of the canal of Nuck (female hydrocele)

In women, a diverticulum of peritoneal membrane follows the round ligament and extends through the inguinal ring and into inguinal canal. This peritoneal membrane forms the canal of Nuck in women and is analogous to the processus vaginalis testis in men. Occasionally the canal of Nuck fails to close completely during postembryonic development, in which case it may fill with serous fluid, forming a cyst (female hydrocele). This type of cyst presents clinically as a skin-colored, asymptomatic mass in the inguinal canal or labium majus (Figure 23.6). No treatment is necessary but surgical removal can be carried out if the patient views the cyst as troublesome.

Mucinous cysts

Mucinous cysts occur quite commonly in the vulvar vestibule. They arise, presumably as a result of outlet blockage, from the numerous minor vestibular glands that occur in that location. Their size is variable (2–15 mm), as is the color, which may be translucent, skin-colored, light blue, or yellow (Figures 23.7 and 23.8). These lesions are asymptomatic and require no therapy.

Figure 23.7 This mucinous cyst is yellow, although some are skin-colored or blue.

(Reproduced from P. J. Lynch and L. Edwards Genital Dermatology (Fig. 10-10), New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994.)

Melanocytic nevi (moles)

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Several studies have looked at the prevalence of nevi on the vulva but the diagnosis was made on a clinical basis. Only one study included biopsies to determine the underlying nature of the pigmented lesions2. In that study most of the pigmented lesions turned out to be lentigines rather than nevi. Lentigines are discussed in Chapter 22. Nevi occurred in 2.3% of patients. All of these patients were Caucasian; no nevi occurred in the small number of Asian or African American women who were examined. One of the nevi showed some atypical features but the other six were histologically benign.

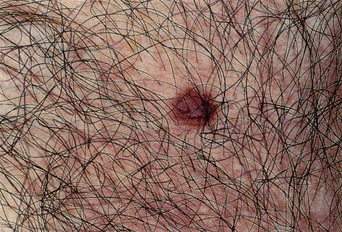

Nevi may appear as flat macules or raised papules. Typical, normal nevi are brown to black, evenly pigmented, sharply marginated, and 2–10 mm in diameter (Figures 23.9–23.13). Occasionally, nevi that are papular may appear tan or skin-colored because of their sparse melanin production. Nevi may be located on either the mucosal or hair-bearing regions of the vulva. Patients with darkly pigmented skin tend to have darker nevi, but note that dark color alone says nothing about malignant potential. Nevi may be present at birth and, in general, these tend to be larger, darker lesions (Figure 23.14). Acquired nevi begin to develop in childhood and may increase in number during early adult life. After mid-adult life, the number of nevi gradually decreases.

(Reproduced from P. J. Lynch and L. Edwards Genital Dermatology (Fig. 12-5), Churchill Livingstone.)

Figure 23.11 A typical soft, small, regular nevus on the mons.

(Reproduced from P. J. Lynch and L. Edwards Genital Dermatology (Fig. 12-6), Churchill Livingstone.)

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

Most elevated pigmented nevi are easily recognized as such (Table 23.1). They differ from seborrheic keratoses in that the latter lesions have a rough, scaling surface. Small, flat nevi are identical in appearance to lentigines. Melanomas have a history of enlargement and the pigment may be more variegated. Skin-colored papular nevi are similar in appearance to fibroepithelial polyps. Other pigmented lesions to be considered include pigmented warts and the pigmented lesions of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). In all of these situations, biopsy will allow for correct diagnosis.

| Diagnosis |

| Brown to black color |

| Smooth-surfaced |

| Flat macules or elevated papules |

| Biopsy |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| Lentigines |

| Melanoma |

| Seborrheic keratoses |

| Pigmented warts |

| Pigmented vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia |

| Therapy |

| None needed |

| Excisional biopsy if diagnosis is uncertain |

Clinical findings that suggest histological atypia or even the presence of a melanoma include asymmetrical configuration, irregular or indistinct borders, uneven pigmentation (especially with red and white hues), and diameter larger than about 7 mm. A history of change in a pigmented lesion is also useful but women are only rarely aware of change in pigmented lesions in the seldom-inspected tissue of the vulva.

Pathogenesis

Nevus cells are rounded-up, nondendritic, pigment-producing cells that are derived from melanocytes. A clonal population of nevus cells can form clusters (“nests”) in the epidermis (junctional nevi), nests in the dermis (dermal nevi), or in nests located both in the epidermis and the dermis (compound nevi). Nevi may be present at birth or may be acquired. Nevi begin to develop in childhood but the number increases appreciably in the second and third decades. After mid-adult age, nevi regress and slowly decrease in number. On average a light-skinned person will have 15–50 nevi by age 30. Factors increasing the likelihood of acquiring nevi include light skin pigmentation, a positive family history for nevi, and sunlight exposure.

Skin tags and fibroepithelial polyps

Skin tags, also known as acrochordons, are extremely common. Approximately half of all adults have them. They occur more frequently in obese individuals and are somewhat more common in women than in men. Typical locations for skin tags are the axillae, neck, groin, and anogenital area. Small lesions are soft, skin-colored or tan, pedunculated papules (Figure 23.15). Most are about 2 mm in diameter at the base and 4–10 mm tall. Larger nodules are termed “fibroepithelial polyps”; some of these may be several centimeters in size (Figure 23.16). Fibroepithelial polyps have particular predilection for the labia majora, upper inner thighs, and buttocks. The histology is similar in both types, with a normal epidermis enclosing loose connective tissue and dilated capillaries. Fat cells are found in the larger fibroepithelial polyps and account for the very soft feel of these lesions on palpation.

Figure 23.15 A soft, skin-colored, pedunculated papule within skin folds that is typical for a skin tag, or acrochordon.

Skin tags are always benign. Treatment may be indicated if they become irritated or infarcted. Removal can be carried out with scissor excision, with or without local anesthesia, depending on size. Alternatively, they can be destroyed with electrosurgery or cryotherapy. Electrosurgery usually requires local anesthesia and cryotherapy is most easily handled by grasping the lesion with forceps and then freezing the forceps until the lesion frosts over. Patients can remove their own lesions by tying a thread tightly around the base. The tags then undergo necrosis and fall off in 7–10 days.

Seborrheic keratoses

Seborrheic keratoses occur as sharply marginated, square-shouldered, pigmented papules 3–20 mm in diameter. Height from the skin surface ranges from 2 to 10 mm. The surface is usually rough to palpation and scale is often visible (Figures 23.17 and 23.18). Note that both of these attributes may be less apparent when seborrheic keratoses develop in moist areas. Most of the lesions are brown but the color varies from light tan to dark black. Seborrheic keratoses only arise on hair-bearing skin and are most commonly located on the trunk and upper extremities. Their prevalence increases with age, rising from about 10% in the third decade to 90% in the eighth decade. In the anogenital area, seborrheic keratoses may be found on the mons pubis, thighs, buttocks, genitocrural folds, and labia majora. Examination with magnification (dermoscopy or vulvoscopy) may reveal the typical small pits that characterize seborrheic keratoses3.

Figure 23.17 The flat-topped keratotic nature of these brown lesions is classic for seborrheic keratoses.

The differential diagnosis for seborrheic keratosis includes warts, VIN, nevi, and melanoma. When the surface of a seborrheic keratosis is scraped with a blade, scale becomes apparent. This is a helpful diagnostic clue since scale is not apparent when nevi and melanomas are scraped. Differentiation from warts and VIN may be difficult. Seborrheic keratoses usually occur as solitary lesions in the anogenital region, whereas warts and VIN are most often multifocal (Figure 23.19). Shave removal for biopsy should be carried out in most instances where there is diagnostic question but if melanoma is a strong consideration, excisional biopsy is preferred. Biopsies from lesions mistakenly considered to be seborrheic keratoses in nongenital areas reveal the presence of melanoma in about 0.5% of specimens4.

Seborrheic keratoses probably arise as clonal proliferations of epithelial cells. A significant proportion of the cells demonstrate mutations5. Cell markers for proliferation and inhibitors of apoptosis are also regularly present6. For some time questions have been asked about what, if any, role human papillomavirus (HPV) infection plays in the etiology of seborrheic keratoses. This controversy currently remains unresolved, though most clinicians believe that lesions of this type demonstrating the presence of HPV DNA are actually misdiagnosed warts.

Clinically typical seborrheic keratoses are benign lesions and no therapy is necessary. Lesions that are inflamed or otherwise troubling to the patient are best treated with cryotherapy7.

Hemangiomas

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Anogenital hemangiomas develop from a red patch but by the time most are recognized they are smooth-surfaced, soft, red nodules varying in diameter from 1 to 10 cm. Less often the lesion appears as a flat, elevated plaque (Figures 23.20 and 23.21). When superficial vessels make up the bulk of the lesion, the color is bright red but when deeper vessels are the ones primarily involved, the color takes on a violaceous or blue hue. Usually only a solitary lesion is present but, in the condition known as hemangiomatosis, multiple lesions are noted. Hemangiomas tend to enlarge slowly over a few months, at which point they stabilize in size. Spontaneous regression, sometimes with scarring, is highly likely by age 5–8 years.

(Reproduced from P. J. Lynch and L. Edwards Genital Dermatology (Fig. 22-4), Churchill Livingstone.)

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on clinical findings. Biopsy is contraindicated as bleeding at the time of biopsy can be quite troublesome. There are very few lesions that can be confused with infantile hemangiomas, though the red lesions described in Chapter 19 along with amelanotic melanoma could be considered (Table 23.2).

| Diagnosis |

| Occurrence in newborn and neonates |

| Red to violaceous color |

| Smooth-surfaced |

| Flat patches becoming papules and nodules |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| Pyogenic granulomas |

| Amelanotic melanoma |

| Biopsy is contraindicated |

| Therapy |

| Usually no therapy is indicated |

| Topical antibiotics if ulcerated |

| Large hemangiomas occasionally require intralesional steroids, systemic steroids, or laser ablation |

Therapy and prognosis

Usually no therapy is necessary. Unfortunately hemangiomas occurring in the anogenital area ulcerate fairly frequently. These ulcerated lesions may be painful and may be accompanied by bleeding or infection. Topical antibiotics such as bacitracin or mupirocin are recommended for all ulcerated lesions. Systemic antibiotics should be used if there is evidence of sepsis. These ulcerated hemangiomas respond to a varying degree when treated with pulsed-dye laser therapy or intralesional corticosteroid injection. In desperate situations, oral steroids may be used. Most hemangiomas resolve spontaneously, though a subset of those present at the time of birth are noninvoluting.

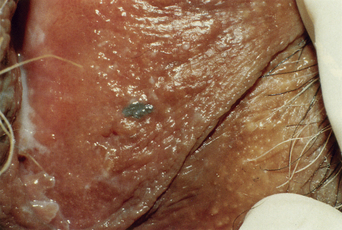

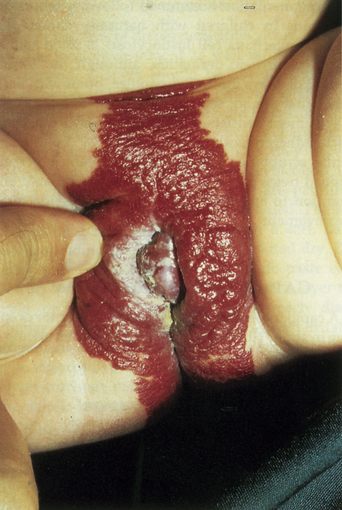

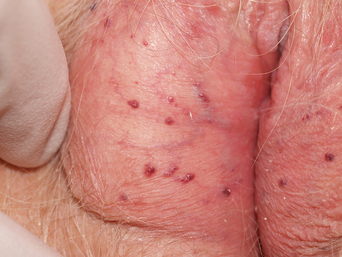

Angiokeratomas

Angiokeratomas occur as age-related, minute varices on the scrotum of men and the vulva of women. In contrast to scrotal lesions, angiokeratomas in women are fewer in number (usually 1–10), larger in size (3–6 mm), and darker (violaceous to blue) in color (Figures 23.22 and 23.23). The lesions appear in adult life. Histologically there is dilation of superficial capillaries overlaid by a slightly thickened epidermis, demonstrating elongation of the rete ridges to partially surround the dilated vessels. In a simplistic manner, these lesions can be thought of as tiny varices. They are asymptomatic and, unless there is frequent bleeding secondary to trauma, no treatment is needed. Symptomatic lesions can be excised or can be destroyed using electrosurgery.

Figure 23.22 Multiple angiokeratomas are common, red to purple, and most often found on the labia majora.

Syringomas

Syringomas occasionally develop on the vulva, though this is an uncommon finding. Fewer than 50 cases have been reported in the literature and in one older series from a vulvar disease clinic, vulvar syringomas were found in only one of 1100 consecutive patients examined. Almost all vulvar syringomas are found on the labia majora where they appear as clustered papules 5–20 mm in diameter. The papules are sloped-shouldered and smooth-surfaced. Most are skin-colored but white, yellow, and brown hues have been reported (Figures 23.24 and 23.25). Onset is usually in late childhood or early adult life. Pruritus occurs in a considerable proportion of the patients and in some cases it can be severe, leading to superimposed lichen simplex chronicus. Once present, lesions persist indefinitely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree