CHAPTER 18 Vulvar Dermatoses: the Eczematous Diseases

The eczematous diseases account for a very large proportion of all disorders occurring in the vulvar area. Most of the eczematous diseases are quite symptomatic and this leads to high demand for attention from patients and rapid patient dissatisfaction when the problem is not quickly recognized and appropriately treated.

The morphology of the eczematous diseases overlaps with that of the papulosquamous diseases (see Chapter 17). The three morphological features that the eczematous diseases share with the papulosquamous diseases include red color, overlying scale, and elevated papules and plaques. However the eczematous diseases do have three distinctive morphologic features that help to separate them from the papulosquamous diseases: (1) the presence of indistinct lesional margination; (2) evidence of epithelial disruption; and, in the special case of pruritic eczematous disease, (3) lichenification.

Epithelial disruption: When the epithelial barrier layer is intact it allows no clinically perceptible passage of fluid in either direction across it. An intact epithelial barrier layer is found in the papulosquamous disease but it is disrupted in the eczematous diseases. There are five signs, any one or combination of which indicates the presence of epithelial disruption: (1) easily visible linear or angular erosions due to excoriation; (2) barely visible narrow erosions in the form of fine fissures; (3) a wet surface due to “weeping” or “oozing”; (4) crusting, due to the evaporation of surface water leaving dried plasma proteins. The color of crust is yellow (when no blood cells are present) and red, purple, or black (when blood cells are present); and (5) yellow scale, due to minimal fluid flow which colors existing scale rather than building up as crust.

Atopic/neurodermatitis and lichen simplex chronicus

Atopic/neurodermatitis and its localized variant lichen simplex chronicus are by far the most important of the conditions found in the eczematous disease category. In fact, this form of eczematous disease is so important that the entirety of Chapter 16 is devoted to this subject. A clinician faced with vulvar lesions possessing the morphology of an eczematous process (as defined above) that is accompanied by persistent scratching and rubbing is almost certainly dealing with lichen simplex chronicus. In such a situation the material in Chapter 16 should be reviewed as it will allow for confirmation of diagnosis and establishment of an effective therapeutic program.

Contact dermatitis

Irritant contact dermatitis

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

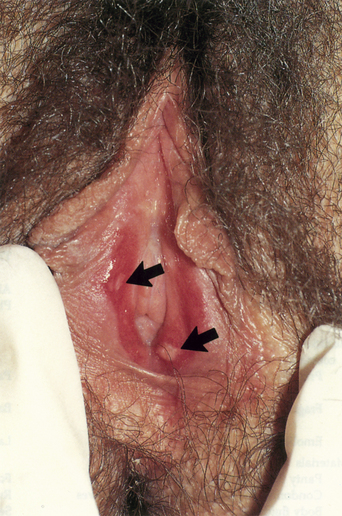

Irritant contact dermatitis can be acute or chronic in type1. In acute contact dermatitis, the contactant causing the problem is so damaging that only one or two exposures are enough to create a marked inflammatory response. There is also only a short time period between the point of exposure and the development of the reaction. These two facts make the identification of the contactant quite easy. For patients who withhold history (such as those who are self-destructive and those with obsessive-compulsive behavior), the diagnosis may be less readily apparent. In the instance of acute irritant contact dermatitis, the involved tissue is quite red and often edematous. Pain is present, scale is minimal, and the surface may be eroded (Figures 18.1 and 18.2).

Figure 18.2 Harsh disinfectants have produced an exudative, vesicular, and edematous acute irritant dermatitis.

(Reproduced from P. J. Lynch and L Edwards Genital Dermatology (Fig. 5-12), New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994.)

On the other hand, the development of chronic contact dermatitis is due to a less damaging contactant requiring multiple exposures over a longer time frame. In this situation, tissue swelling is minimal and redness, often with dusky or violaceous hues, is less intense (Figure 18.3). Fine cracks and fissures may be noted and the vulva may appear dry and chapped. Some scale is likely to be present. Symptoms are usually those of mild burning or irritation; itching is not usually a prominent feature.

Diagnosis and differential diagnoses

Nearly all of the other papulosquamous and eczematous diseases have to be considered (Table 18.1). Sometimes it is difficult to separate irritant contact dermatitis from allergic contact dermatitis2. The correct diagnosis depends on obtaining a thorough history of what the patient has been applying to her anogenital area. Unfortunately, patients are often forgetful about what they are using and also may be reticent or ashamed to list everything. For this reason, questions about what products are being used must be asked on multiple occasions. It is also helpful to ask the patient to go through her medicine cabinet and, at the time of the next visit, to bring in every topical agent that is found there.

Table 18.1 Irritant Contact Dermatitis

| Diagnosis |

| Flat, dusky red, chapped, eczematous patches |

| History of products which overdry or macerate skin |

| History of excessive hygiene |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| Candida vulvitis |

| Allergic contact dermatitis |

| Atopic/neurodermatitis |

| Lichen simplex chronicus |

| Seborrheic dermatitis |

| Therapy |

| Identify and remove irritants |

| Low- (1% hydrocortisone) or medium-strength (0.1% triamcinalone) steroid ointments |

Pathogenesis

In acute irritant contact dermatitis, the irritants are directly cytotoxic to epithelial cells. Most of the strong irritants are physician-ordered or applied medications such as flurouracil, imiquimod, trichloroacetic acid, and podophyllin1. However, one should never underestimate what products women might apply to the vulva when they are desperate or obsessed. We have seen reactions to bleaches, lye, kerosene, and many other unusual substances.

On the other hand, in the majority of young and middle-aged women, the problem is one of excess dryness due to unnecessary, inappropriate or overly energetic hygiene. Some women have grown up with the notion that “the area down there” is “dirty” and must be scrubbed frequently and vigorously. In other instances, women overdo washing because they are worried about real or imagined odor. Water that is too hot, detergents that are too harsh, and toweling that is too brisk are commonly the culprits. But, in addition, “normal” soap and water washing may be carried out too frequently, i.e., more than twice daily.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

The prevalence of allergic contact dermatitis is difficult to determine. In those clinical settings where patch testing for women with vulvar dermatitis is carried out on a regular basis, about 50% (range 38–78%) of patients have developed one or more positive tests1,3. These patch tests were deemed clinically relevant in about 30% of all women with positive tests1,3,4. However, in clinics where patch testing is carried out infrequently, the percentage of positive patch tests, and hence the purported incidence of allergic contact dermatitis, is much lower. How much lower is difficult to say, but we believe it is less that 5%. At this point, it is not possible to explain this wide discrepancy.

The clinical appearance of allergic contact dermatitis is that of bright red, edematous papules and plaques (Figure 18.4). Scale is not prominent and may be absent. Pruritus is marked and excoriations may be present. An element of the itch–scratch cycle (lichen simplex chronicus) often develops, creating a confusing clinical picture.

Initial sensitization to an antigen takes 7–10 days but, once sensitization is present, reapplication of the antigen results in an inflammatory reaction within minutes to hours. For this reason, the appearance of allergic contact dermatitis to a new product is delayed for days but reapplication at a later time quickly causes symptoms and signs.

Diagnosis and differential diagnoses

The clinical appearance of allergic contact dermatitis can overlap with that of irritant contact dermatitis2 but brighter red color, presence of edema, lack of a chapped appearance, and prominent itching point more toward an allergic reaction (Table 18.2). Other eczematous diseases such as lichen simplex chronicus and seborrheic dermatitis are also similar in appearance. Even candidiasis and papulosquamous conditions, to include psoriasis and tinea cruris, need to be considered.

Table 18.2 Allergic Contact Dermatitis

| Diagnosis |

| Bright red eczematous plaques |

| History of topical medication use |

| Consider patch testing |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| Candida vulvitis |

| Irritant contact dermatitis |

| Atopic/neurodermatitis |

| Lichen simplex chronicus |