CHAPTER 17 Vulvar Dermatoses: Papulosquamous Diseases

Inflamed, scaling skin diseases fall into two morphologic groups; papulosquamous disease and eczematous disease. Papulosquamous diseases are well demarcated and usually show little evidence of rubbing and scratching. Eczematous disease is characterized by poorly demarcated borders, and either excoriations or thickening from rubbing (lichenification) are generally prominent.

Psoriasis

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Psoriasis occurs in approximately 1–3% of the population1. Anogenital involvement is common and usually accompanied by disease on other areas of the body. Psoriasis occurs in all races, and at all ages, but most patients exhibit lesions before the age of 30 years. Obesity and alcoholism are more prevalent in patients with psoriasis.

The clinical appearance of psoriasis varies as this disease occurs in several major patterns (Table 17.1). Most common is psoriasis vulgaris (common psoriasis, or plaque-type psoriasis). Psoriasis vulgaris is manifested by classic well-demarcated, red plaques covered with dense, silvery scale (Figures 17.1 and 17.2). In skin folds, however, the scale is more subtle, often with a shiny or glazed texture (Figure 17.3) Psoriasis vulgaris shows a predilection for elbows, knees, and scalp, although it can occur in all areas. Psoriasis exhibits the Koebner phenomenon, in which the disease preferentially affects areas of trauma or inflammation. This partially explains the distribution of elbows, knees, and genital skin – all areas prone to friction and mild trauma. Many patients also exhibit tiny pits on the fingernails, a relatively specific sign of psoriasis.

Table 17.1 Morphologic Variants of Psoriasis

| Psoriasis vulgaris – well-demarcated scaling, large plaques with predilection for elbows, knees, scalp |

| Guttate psoriasis – 0.5–2 cm, lightly scaling, widely scattered plaques |

| Inverse psoriasis – moist, deep red plaques in skin folds |

| Erythrodermic psoriasis – generalized erythema and scale |

| Pustular psoriasis – erythematous plaques of pustules and crusting |

A second form of psoriasis, guttate psoriasis, appears as 0.5–2-cm round, red, scaling papules and small plaques (Figure 17.4). Scalp and nail disease are less common, and this form of psoriasis does not prominently affect anogenital skin, elbows, knees, or scalp.

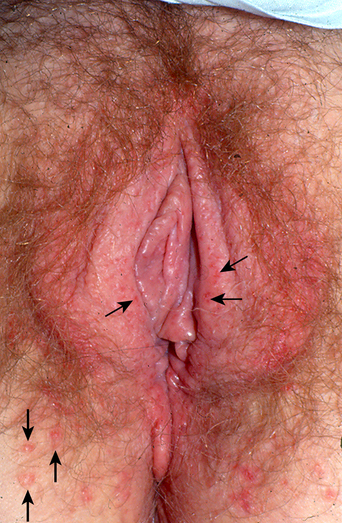

Inverse psoriasis consists of disease that preferentially affects skin folds, including the axillae, inframammary skin, crural creases, and anogenital area. Inverse psoriasis consists of moist plaques that are deeply red, with very subtle scale (Figures 17.5–17.7). The thickened skin in skin folds is often macerated and appears white. The gluteal cleft and umbilicus are characteristically also involved. Often, classic elbow, knee, and scalp psoriasis are absent.

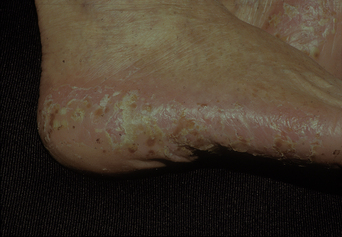

The final form of psoriasis is pustular psoriasis, which appears as plaques of pustules that eventuate into crusted plaques. These can be generalized or occur primarily on the hands, feet, and genital skin. The skin findings of pustular psoriasis are indistinguishable from those of Reiter’s syndrome (Figures 17.8 and 17.9). Arthritis is more common with pustular psoriasis than with other forms.

Except for guttate psoriasis, all variants of psoriasis frequently exhibit anogenital involvement, and inverse psoriasis nearly always affects the vulva and crural creases. Psoriasis usually affects hair-bearing, nonmucous membrane anogenital skin. However, pustular psoriasis rarely occurs on the modified mucous membranes of the vulva, the vaginal epithelium, and ectocervix.

Differential diagnosis

Diseases that mimic genital psoriasis include candidiasis, which is also characterized by red, intertriginous plaques, but candidiasis is usually accompanied by small satellite papules and collarettes, and a positive fungal preparation or culture. Clearing with anticandidal therapy confirms that diagnosis. Tinea cruris, although uncommon in women, sometimes appears indistinguishable from anogenital psoriasis. Lichen simplex chronicus of the labia majora and mons is morphologically similar to psoriasis but generally is less well demarcated. Seborrheic dermatitis is very uncommon on the vulva, but appears similar clinically and histologically, with red, moist, finely scaling red plaques on the vulva and crural creases. Seborrheic dermatitis is regularly accompanied by typical seborrhea of the scalp, central face, and other skin folds. The red, rough plaques of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis sometimes resemble psoriasis, but are classically less well demarcated and unaccompanied by signs of extragenital psoriasis. The above diseases are differentiated by culture, the identification of characteristic lesions elsewhere, and response to therapy. Often, psoriasis coexists with one of these diseases, especially candidiasis, lichen simplex chronicus, and contact dermatitis (Table 17.2).

| Diagnosis |

| Clinical appearance |

| Red, well-demarcated, scaling or moist plaques |

| Usually absent on modified mucous membrane and vagina |

| Frequent involvement of scalp, nails, elbows, knees |

| Confirmed on biopsy when not classic |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| Reiter’s syndrome |

| Lichen simplex chronicus |

| Candidiasis |

| Irritant and allergic contact dermatitis |

| Tinea cruris |

| Seborrheic dermatitis |

| Erythrasma |

| Management |

| Topical corticosteroids, triamcinolone 0.1% ointment applied twice daily and tapered when possible, or the more potent clobetasol propionate ointment used twice daily and tapered quickly to once three times a week |

| Topical calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice daily |

| Systemic medications for severe recalcitrant disease, including methotrexate, retinoids, cyclosporine, etanercept, infliximab, efalizumab, etc. |

Pathogenesis

Psoriasis is an immunologically mediated disease characterized by a T-cell inflammatory infiltrate2. This T-cell-mediated type 1 autoimmune process and the resulting cytokines ultimately produce an increased turnover of keratinocytes, thickening of the epidermis, and scale. The predilection for the development of psoriasis is partly inherited.

Therapy and prognosis

Vulvar psoriasis is usually controllable with topical therapy. Corticosteroids, the elimination of irritants, and careful attention to secondary infection, particularly Candida, produce sufficient benefit for most women with anogenital psoriasis. An ultrapotent topical corticosteroid such as clobetasol ointment is applied very sparingly once or twice daily, tapering the application to the least frequent dosing that controls the disease, usually about three times a week. The areas most often affected with psoriasis, the hair-bearing labia majora, crural crease, perianal skin, and medial thighs, are the areas that atrophy very easily. Patients who require ongoing daily therapy should be managed with a lower-potency topical corticosteroid, and, if needed, calcipotriene (Dovonex) cream. Other topical agents, such as tar, salicylic acid, and anthralin, are too irritating for use on anogenital skin. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are useful in some patients, and although somewhat irritating, some women tolerate them well, particularly after the skin is partially controlled with a topical corticosteroid.

Psoriasis cannot be cured, but it can be controlled. Psoriasis of the anogenital skin is usually more easily controlled than psoriasis of other areas, but corticosteroid side-effects are also more prominent here so that ongoing surveillance is indicated. Secondary anogenital malignancy has not been reported, but deforming arthritis is a known sequela and there is recent evidence that the inflammation of psoriasis may predispose to coronary artery disease3.