CHAPTER 13 Vulvar Anatomy

Introduction

The vulva is the area of the female body located between the genitocrural folds laterally, the mons pubis anteriorly, and the anus posteriorly. The internal border of the vulva is represented by the hymeneal ring. The vulva has a variety of appearances, dependent on the age and ethnicity of the patient.

Embryology

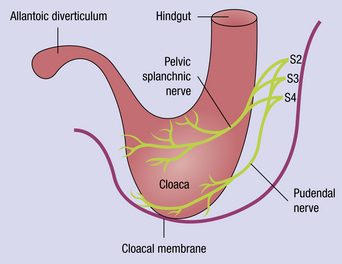

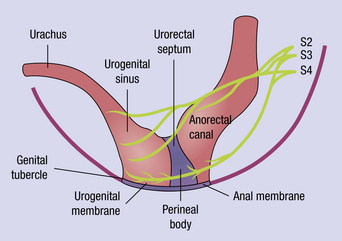

The urogenital and alimentary systems share a common reservoir, the cloaca, until 5 weeks’ gestation. This is derived from the caudal region of the hindgut (Figure 13.1), and is separated from the surface by the cloacal membrane. Between 5 and 7 weeks’ gestation, the mesoderm migrates distally to become the urogenital septum, dividing the cloaca into the larger urogenital sinus and the anorectal canal. The septum eventually fuses with the cloacal membrane to produce the anal membrane and the urogenital membrane, with the genital tubercle superiorly (Figure 13.2). The close embryologic derivation of the vulva and anus is reflected in the common blood supply and nerve supply of these areas, and the numerous dermatologic conditions that affect both organs in a similar manner.

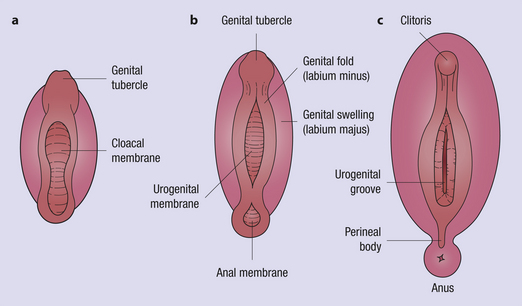

By about 7 weeks, the cloacal membrane is divided into a urogenital membrane and an anal membrane (Figure 13.3), with an anterior genital tubercle, two symmetric genital folds, and two genital swellings. At 8–9 weeks’ gestation, if testes are present, Leydig cells begin producing testosterone. If the target cells in the external genitalia contain the enzyme 5-alpha-reductase, testosterone is converted into dihydrotestosterone, and by 10 weeks’ gestation, male structures develop. If no testosterone is produced, or the reductase enzyme is not found in the epithelial cells, a vulva develops1. The entire conversion to female structures is completed by 20 weeks’ gestational age.

The hymen is a remnant of the urogenital membrane. Several variations in the embryologic development of the hymen may occur and result in microperforations, fenestrations, bands, septa, and differences in rigidity and/or elasticity of the tissue. There are various types of hymeneal perforations. In rare cases, the hymen may be imperforate, causing the retention of menstrual blood behind it and giving rise to a hematocolpos (Figure 13.4).

The secondary sex characteristics appear earlier in the male fetus than in the female fetus, probably reflecting the earlier functional activity in the testis. The Y chromosome induces the gonad to become a testis in the genetically male fetus. The differentiation of the external genitalia in the female occurs because this male-determining effect is not present. Androgen contact with the epithelium at this time results in an androgenic influence on the external genitalia. Reasons for androgenization in the female include drug or exogenous hormone intake, placental aromatase deficiency, maternal androgenic tumors, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The end result is female pseudohermaphrodite with ambiguous genital development1.

The normal vulva

The vulva contains the following structures that form the female external genitalia (Figures 13.5 and 13.6), including:

It is important to understand the anatomy of the vulva and to appreciate pathologic abnormalities that occur in the various locations of the vulva. Table 13.1 outlines some of the various pathologic abnormalities that may occur at the corresponding anatomic locations of the vulva.

Table 13.1 Anatomic Locations with Site-Specific Corresponding Conditions

| Mons pubis | Pediculosis pubis |

| Urethral orifice | Skene duct cyst |

| Prolapse | |

| Caruncle | |

| Diverticulum | |

| Labium majus | Syringoma |

| Interlabial sulcus | Papillary hidradenoma |

| Labium minus | Lichen sclerosus |

| Labial hypertrophy | |

| Labial agglutination | |

| Bartholin gland orifice and duct | Bartholin’s cyst or abscess |

| Vestibule | Vestibulodynia |

| Mucous cyst | |

| Hymen | Imperforate hymen |

| Anus | Condylomata acuminata |

| Preinvasive or invasive vulvar conditions | |

| Perineum | Obstetrical injuries |

| Genitocrural folds | Yeast infections |

| Intertrigo | |

| Clitoris | Hypertrophy |

| Prepuce | Abscess |