CHAPTER 24 Vaginitis

Vaginitis and vaginosis refer to vaginal infections, skin diseases involving the vagina, or a disruption of the normal vaginal flora. Common and nonspecific symptoms include vaginal discharge, odor, introital itching, or irritation. Vaginosis refers to vaginal disease unassociated with inflammation as characterized by redness and a wet mount showing an increase in white blood cells. Vaginitis is associated with clinical and wet-mount changes of inflammation.

Candida vulvovaginitis

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

About 75% of women experience vaginal candidiasis at some point in their life1. Candida vaginitis is more common with antibiotic therapy, diabetes, human immunodeficiency viral infection, and pregnancy. Although Candida vulvitis occurs at any age in a setting of obesity and incontinence, vaginal Candida does not generally occur in the absence of estrogen. Therefore, premenarchal girls almost never develop vaginal yeast, and postmenopausal women not on estrogen replacement are usually spared vaginal yeast also2.

Most women describe introital itching as an early sign of Candida vulvovaginitis. Those women with more marked vulvar involvement experience interlabial and skin fold fissures and excoriations that produce burning, stinging, and dyspareunia (Figures 24.1 and 24.2).

Figure 24.1 Candida vaginitis usually produces redness and puffiness of the modified mucous membranes of the vulva.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of C. albicans includes all other causes of vaginitis (Table 24.1) as well as red vulvar plaques, including psoriasis, lichen simplex chronicus, seborrheic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, and tinea cruris. Non-albicans Candida, particularly C. glabrata, is most often confused with vestibulodynia (vulvar vestibulitis syndrome) or generalized vulvodynia (Table 24.2). Trichomoniasis and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV) superficially resemble Candida vaginitis, but vaginal secretions are most often grossly purulent with those diseases.

Table 24.1 Candida albicans and C. tropicalis Vaginitis

| Diagnosis |

| Pruritus in setting of vestibular erythema, sometimes vulvar edema |

| Often clumped, white vaginal secretions |

| Wet mount showing mycelia and budding yeast |

| May be confirmed by culture when atypical, recurrent, or resistant |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| All other causes of vaginitis; statistically most often Trichomonas, bacterial vaginosis |

| Physiologic discharge |

| Vulvodynia/vestibulodynia (vulvar vestibulitis) |

| Management |

| Topical |

| Any azole cream or tablet/suppository inserted into vagina according to package insert (miconazole, clotrimazole, terconazole, tioconoazole, butconazole) |

| Nystatin ointment/tablets bid for 1 week |

| Orala |

| Fluconazole Orala 150 mg once |

| Itraconazoleb 200 mg once, or daily from 2 to 7 days |

| Terbinafineb 500 mg daily for 1 week |

| Ketoconazoleb,c 200 mg daily for 5 days |

a Medication interactions can occur with azoles, particularly ketoconazole.

b Not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for vaginal candidiasis.

c Ketoconazole has been associated with idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity.

Table 24.2 Non-albicans Candida Vaginitis

| Diagnosis |

| Introital burning, irritation, very often asymptomatic |

| No discharge |

| Wet mount showing budding yeast without mycelia |

| Confirmed by culture in order to type |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| All other causes of vaginitis, most often desquamative inflammatory vaginitis |

| Vestibulodynia (vulvar vestibulitis) |

| Management |

| A standard trial of any therapy for Candida albicans can be given, but expect nonresponse and re-evaluate for response to therapy. Then: |

| Topical |

| Boric acid capsulesa 600 mg, inserted in vagina at bedtime; if tolerated, twice daily for 2–4 weeks. When more comfortable, if cure not effected, three times a week to suppress |

| Nystatin ointment/tablets bid for 2–4 weeks; may require ongoing suppressive dosing |

| Flucytosine 500 mg capsules, #14 dissolved in 45 grams of hydrophilic base, 6.4 g inserted daily until gone |

| Amphotericina 50 mg compounded vaginal suppositories inserted qd for 2 weeks |

| Amphotericin/flucytosinea inserted daily |

| Systemic |

| Any oral antifungal can be tried, including in combination with topical therapy. Several new antifungal medications show greater in vitro effects against non-albicans Candida species, but none has cleared a patient in this author’s office |

| In extraordinary circumstances, intravenous amphotericin B can be used and sometimes cures infection |

a Not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for vaginal candidiasis.

Pathogenesis

Yeast vaginitis is most often produced by C. albicans, but non-albicans Candida infections are increasingly common. These include C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, as well as other Candida species. C. albicans and C. tropicalis produce mycelia and invade the upper layers of the epithelium, provoking an inflammatory response. Other non-albicans Candida species do not exhibit mycelia, are characterized by budding yeast which attach to the surface epithelium, and incite inflammation. C. tropicalis closely resembles C. albicans in morphology and response to therapy, and for practical purposes does not require differentiation from this common yeast.

Laboratory abnormalities and histology

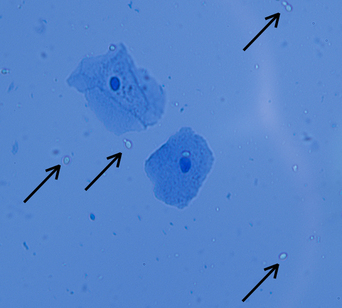

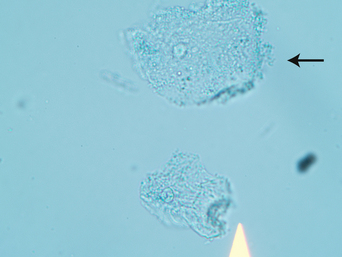

There are no laboratory abnormalities except for cultures which show the offending organisms, and microscopic preparations showing hyphae, pseudohyphae, and budding yeast in the vaginal fluid of women with most infections (Figures 24.3 and 24.4). About 15% of yeast infections show only budding yeast that represent non-albicans Candida. Biopsies show hyphae and pseudohyphae invading upper layers of the epidermis in the case of C. albicans and C. tropicalis. Neutrophils are frequently noted within the epidermis, particularly the upper epidermis.

Figure 24.3 A wet mount of Candida albicans andC. tropicalis shows branching hyphae and budding yeast.

Management and prognosis

Vaginitis produced by C. albicans and C. tropicalis can be cleared with any of a large group of oral or topical medications. Patients with fairly remarkable inflammatory changes of the skin of the vulva may benefit from oral medication such as fluconazole 150 mg to avoid immediate burning side-effects of topical azole cream preparations. This author supplements oral fluconazole with very soothing nystatin ointment applied three or four times a day for women with more than introital vulvar involvement. In addition to fluconazole, itraconazole and ketoconazole are oral medications that have been used for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Terbinafine is a medication available orally and topically and shown to have some anticandidal effect, but it appears somewhat less effective and it does not have US Food and Drug Agency approval for candidiasis3.

Although the treatment of C. albicans is quite easy, with all standard therapies being effective in immunocompetent patients, several issues complicate therapy and predispose to ongoing symptoms. First, recurrent candidiasis is a problem in a significant minority of patients. These patients benefit from chronic suppression with weekly fluconazole 150 mg for several months, which often breaks the cycle4. The use of lactobacillus supplementation has not been shown to be beneficial in the prevention of recurrent yeast infections5. Second, many women have a concomitant process such as lichen simplex chronicus, accounting for much of the symptoms of itching. Third, non-albicans Candida vaginitis can sometimes be extremely resistant to treatment, with patients often responding poorly to azoles. C. krusei is routinely resistant to fluconazole. C. glabrata, the most common species of non-albicans Candida, is often resistant to azoles. Medications that have been used for non-albicans Candida include boric acid, nystatin, flucytosine, and amphotericin6–8. Sometimes, the use of combination or prolonged therapy is required, and sometimes patients never clear, but ongoing twice- or thrice-weekly dosing allows patients to be comfortable despite lack of cure. Fourth, resistant C. albicans is certainly recognized in immunosuppressed patients with Candida vaginitis.

Bacterial vaginosis (nonspecific vaginitis, haemophilus vaginitis, gardnerella vaginalis vaginitis, anaerobic vaginitis)

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Bacterial vaginosis occurs primarily in premenopausal sexually active women. It is common, occurring in 29% of women between the ages of 14 and 49 years9.

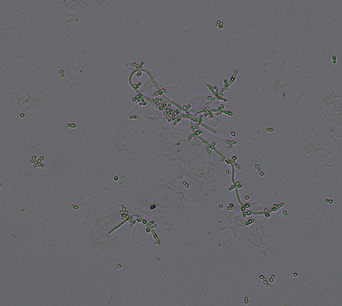

The vulva is nearly normal to inspection without increased redness of the modified mucous membranes of the vulva or of the vagina. Vaginal secretions are classically white and increased in volume. When potassium hydroxide is added to a microscope slide with a drop of vaginal secretions, a distinct fishy odor is released (positive whiff test). A microscopic examination of a wet mount of secretions shows no increase in white blood cells (hence the term “vaginosis” rather than “vaginitis” to indicate the noninflammatory nature of bacterial vaginosis). A wet mount also shows mature epithelial cells and “clue” cells. Clue cells are epithelial cells that are stippled with bacteria so that the cells appear granular, and the borders of the cells are ragged and indistinct due to adherent bacteria (Figure 24.5). Lactobacilli are absent, so the vaginal pH is more alkaline, greater than 4.5.

The guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control dictate that the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is made by the presence of at least three of the following: white, homogeneous, noninflammatory vaginal secretions; the presence of clue cells; a pH of vaginal secretions of greater than 4.5; and a fishy odor of secretions in the presence of an alkali such as potassium hydroxide9a.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

Patients sometimes confuse any other cause of vaginitis, particularly Trichomonas or Candida, with bacterial vaginosis (Table 24.3). However, the criteria of clue cells, fishy odor, and lack of neutrophils for bacterial vaginosis do not show overlap with any other causes of vaginitis.

Table 24.3 Bacterial Vaginosis

| Diagnosis |

| Vaginal discharge |

| pH greater than 5 |

| Microscopic examination showing: |

| Fishy odor of secretions in the presence of an alkaline substance |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| All other causes of vaginitis |

| Management (Center for Disease Control guidelines 2006) |

| Metronidazole 500 mg bid for 7 days |

| Metronidazole .075% gel 5 g daily for 5 days |

| Clindamycin cream 2% 5 g daily for 7 days |

| Clindamycin 300 mg po bid for 7 days |

| Clindamycin 100 g ovules hs for 3 days |

Pathogenesis

The underlying cause of this imbalance of normal bacterial flora is not known. This is not a sexually transmitted disease, and treatment of the partner is not useful. However, sexual activity appears to be a factor, and any condition that decreases lactobacilli appears to predispose to this condition.

Management and prognosis

Generally, clearing bacterial vaginosis is relatively easy. However, recurrent disease develops in about 30% of patients. Those patients who experience recurrent disease can be treated for a more prolonged period of time, sometimes minimizing recurrence10. Treatment of partners does not prevent recurrence.