Absolute indications

Relative indications

Infection

Concomitant meniscal transplant

Femoral tunnel lysis (>15 mm)

Concomitant osteochondral lesion needing articular resurfacing (OATS; ACI)

Tibia tunnel lysis (>15 mm)

Malalignment requiring osteotomy

Failed double bundle ACL reconstruction with large footprint combined tunnel defect limiting fixation or anatomic graft placement

Retained hardware requiring bone removal with subsequent tunnel defect that would compromise anatomic tunnel placement

Arthofibrosis after primary ACL surgery requiring revision of ACL graft following arthroscopic release and manipulation to restore full knee motion

Optimal graft fixation and healing is predicated on healthy, living bone of structural integrity at the aperture of the bone tunnel. Often, removal of hardware, debridement of previous graft back to bleeding bone, and tunnel malposition leading to tunnel overlap during creation can lead to significantly increased tunnel aperture diameters.

Even if suspensory fixation is utilized, the bone must support the graft, and more importantly, have the capacity to promote healing. Therefore, in the absence of adequate bone quantity or quality, a two-staged procedure to optimize the bone should be considered to allow the best chance of graft survival. Ultimately, the decision to expose the patient to the inherent risks of two surgeries is patient-specific and the risks and benefits must be weighed (Table 13.2).

Table 13.2

Considerations for two-stage revision

Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

Possible improvement in postoperative Knee ROM—interval rehab following first stage | Concern regarding continued meniscus or cartilage damage with ACL-deficient knee, interval damage between staged procedures |

Second procedure should be more similar to primary reconstruction—less operative time | Second procedure—surgical and anesthesia associated risk; more prolonged recovery |

Technique

Patient Evaluation and Initial Work-up

The importance of the patient history, examination, radiographic assessment and, if possible, review of prior operative notes cannot be overemphasized. Laxity in the posterior–lateral structures is an important, commonly unrecognized concomitant problem associated with revision ACL patients. Concurrent deficiency has been reported as high as 10–15 % [13] and therefore must be ruled out in the evaluation. Infection with or without ACL deficiency or knee instability always necessitates a staged procedure. However, concomitant ligament laxity or meniscal deficiency, mainly medial, that can affect the long-term survival of the revision ACL construct may be addressed in a single or staged procedure.

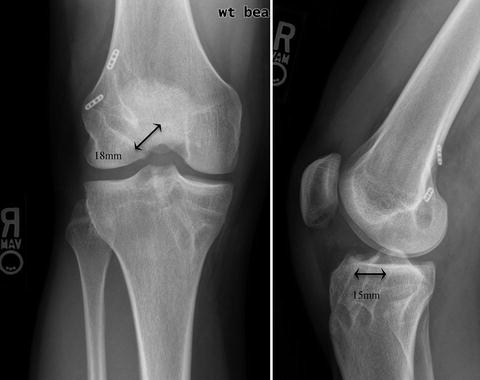

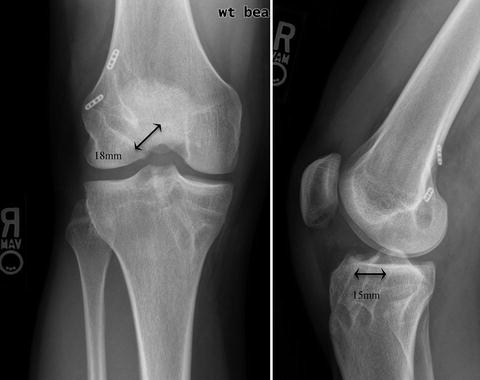

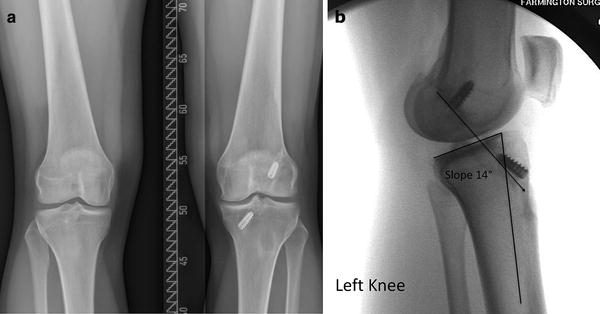

Diameters of bone tunnels should be determined by measuring in two planes—AP and lateral (Fig. 13.1). It is not uncommon that with double bundle ACL reconstructions (Fig. 13.2) or in the case of a prior revision procedure utilizing divergent tunnels, the combined tunnel bone loss at the femoral aperture can be significant enough to warrant staged procedure to facilitate bone grafting. Improper tunnel placement is commonly reported as a reason for ACL graft failure and can be assessed by radiographs [7, 9, 14]. Genu varum or valgum may be present and standing full-length hip to ankle films should be obtained to determine the mechanical axis. High tibial osteotomy (HTO) or distal femoral osteotomy to correct the alignment can be done as part of an initial procedure during which hardware is removed and tunnels grafted to optimize the revision procedure.

Fig. 13.1

Quantification of bone tunnel size, diameter in two planes using AP and lateral radiographs

Fig. 13.2

A radiographic case example of a patient with combined tunnel enlargement following a double bundle ACL reconstruction technique

Case Examples Illustrating Situations in Which a Two-Staged Technique Was Utilized

Case 1: Two-Stage with Femoral and Tibia Tunnel Grafting with HTO with Decreased Posterior Slope

Patient in case example 1 is a 20 y/o college female who was seen as a referral for chronic ACL deficiency, medial meniscal deficiency, and clinical complaint of knee instability limiting activity. A soccer player in high school, who had a primary ACL rupture and reconstruction with autogenous bone-tendon-bone at the age of 16, within 1 year of the surgery the reconstruction failed traumatically during a jump while participating in sport. Within 6 months of the re-rupture she underwent a single-staged revision ACL reconstruction with allograft tendon. Less than 1 year after revision surgery she reinjured the knee and arthroscopic partial medial meniscectomy was performed. She still is very active in many recreational sports but progressive instability and “shifting” of the knee is limiting her ability to be active. During periods of increased activity, she reports mild swelling in the knee and a dull ache localized to the medial aspect of the knee.

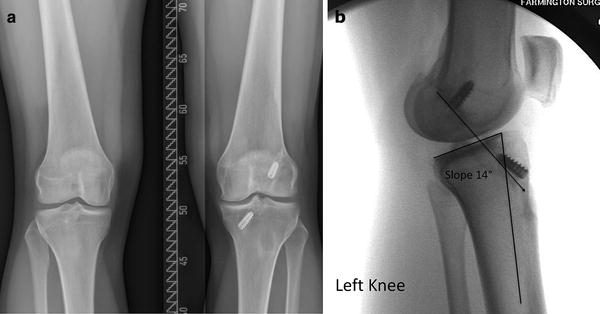

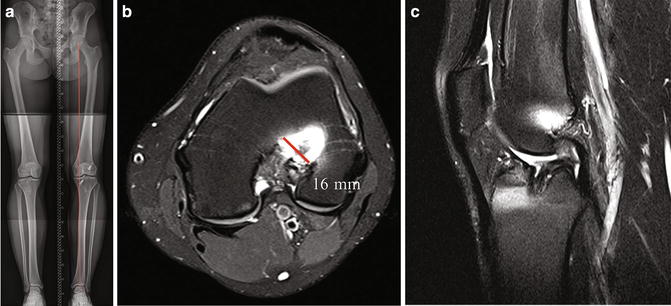

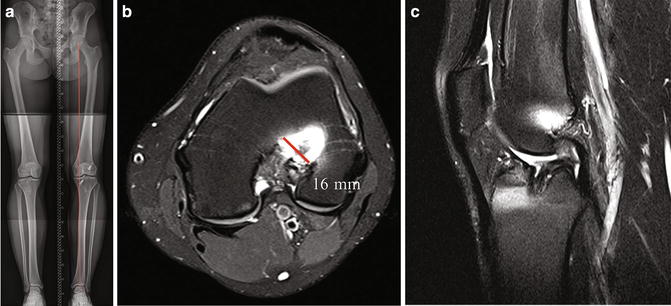

Physical examination demonstrates mild quadriceps atrophy (1.5 cm compared to contralateral), no thrust with ambulation and no increased laxity to the medial or lateral complex with varus and valgus stress at 0 and 30°. Prone dial test negative for increased external rotation. Lachman test is 3+ with no end point, pivot shift present in clinic exam, and markedly positive flexion-rotation drawer. Mild joint line tenderness is present medially and laterally. Posterior drawer demonstrates no laxity and firm endpoint. Radiographs demonstrate mild medial joint space narrowing, enlarged bone tunnels, and a vertical femoral tunnel with a posteriorly placed tibia tunnel (Fig. 13.3). Standing hip to knee radiographs demonstrate genu varum alignment while the MRI confirms ACL deficiency and bone loss at the femoral tunnel aperture that would limit fixation and bone tendon contact for healing (Fig. 13.4a, b).

Fig. 13.3

Initial radiographs, standing, of case example #3. (a) Failed revision ACL of the left knee in a 20 y/o female soccer player. (b) Posterior tibia tunnel placement noted on lateral, increased sagittal plane slope and aperture bone tunnel measurements of 14–16 mm

Fig. 13.4

Preoperative imaging. (a) Standing mechanical axis hip to ankle X-rays demonstrating genu valgus alignment with weight bearing axis in the medial compartment. (b) MRI demonstrating tunnel widening at the femoral tunnel footprint. (c) Lateral MRI demonstrating posterior-positioned tibia tunnel and aperture widening

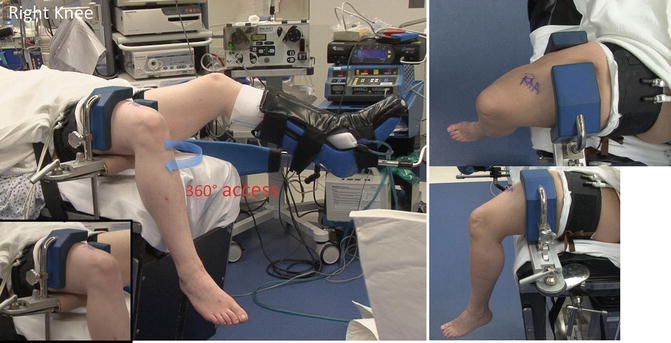

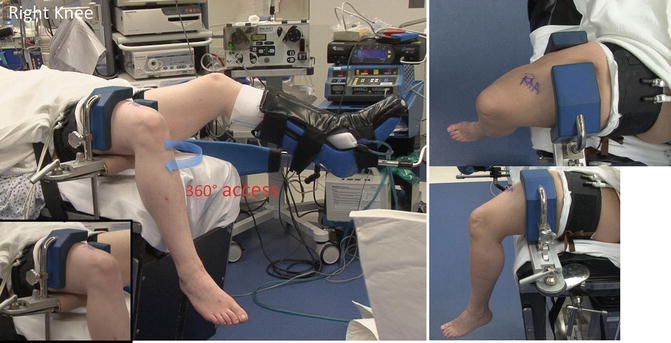

Patient positioning is critical to ensure complete circumferential exposure. We use a circumferential padded knee holder in which the top can be removed to allow for high knee flexion when drilling the femoral tunnel through the low accessory anterior–medial portal (Fig. 13.5). The superior pad on the circumferential leg holder is removed during the case to allow for hyperflexion during femoral tunnel work.

Fig. 13.5

Patient positioning in padded leg holder elevated off the bed. Proximal tourniquet used during the case to facilitate maximal visualization. During hyperflexion of the knee, for femoral tunnel work, the superior–lateral pad is removed by circulating nurse from under the drapes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree