, Paul N. Chugay1 and Melvin A. Shiffman2

(1)

Long Beach, CA, USA

(2)

Tustin, CA, USA

Abstract

The authors focus on the treatment of triceps hypoplasia. There is a description of the basic anatomy of the region. Preoperative marking of the patient and operative procedure are discussed followed by postoperative care and potential postoperative complications. The observed complications are described as well as the management of those complications.

Introduction

As men are increasingly becoming interested in cosmetic surgery, surgeons have to modify procedures and create new ones to meet the needs of the male population [1, 2]. With the advent of the biceps augmentation in 2004, the introduction of the triceps augmentation procedure was a natural progression. Many patients presented for muscle augmentation surgery and wanted a circumferential upper extremity augmentation. As there was no established procedure or formal implant in use, it was necessary to construct an implant that would easily fit below the long head of the triceps or under the deep investing fascia of the arm, depending on the patient’s needs. This implant had to be pliable and yet sturdy enough to resist the constant movement of the arm and contraction of the upper extremity musculature. Using the Chugay Biceps Prosthesis as a starting point, a custom-designed triceps prosthesis was developed to help achieve augmentation in the triceps area for reconstructive and cosmetic needs.

Body Dissatisfaction in Males

It stands to emphasize that many men have some element of body dysmorphic disorder and wish to have a more muscular and “built” physique in order to be better accepted in society and by the opposite sex [3–8]. Society has created an idealistic model of the male that is oftentimes hard to attain with simple diet and exercise alone. For this reason, muscle augmentation surgery of the upper extremity, both biceps and triceps augmentation, gives a male the opportunity to achieve this ideal.

History of the Procedure

Triceps augmentation really takes its early steps in the work done by various surgeons to augment the bicipital region. The biceps implant, as mentioned previously, was initially used by surgeons to help in the reconstruction of soft tissue defects of the upper extremity left by significant trauma or post-oncologic surgery [9]. Hodgkinson further added to the literature on the use of solid silicone implants for restoration of symmetry and addition of volume to traumatized extremities [10]. In his paper from 2006, he discusses the use of silicone implants to add volume to the upper extremity after ruptures of triceps and biceps muscles and in cases of axillary nerve injury that showed degeneration of the deltoid muscle.

Using his experience with biceps augmentation and having a good understanding of the upper extremity musculature and neurovascular structures, the primary author sought to begin performing triceps augmentation not only for restoration of volume following traumatic injury or as a result of congenital abnormalities but to aid those patients who wished to increase the volume of the triceps region purely for vanity [11, 12]. In 2010, the primary author published his work on 14 patients that received triceps augmentation from 2008 to 2010 [13]. All of the initial procedures were performed via an incision in the axilla and placement of the implant primarily in the submuscular plane. In the primary author’s experience, greater risks for complications were possible with placement of the implant under the muscle, as in biceps augmentation, and for that reason the author routinely uses the subfascial plane for augmentation in the vast majority of cases. With placement solely beneath the fascia, the improved contour was similarly noted but without the increased risk of damage to vital neurovascular structures.

In 2012, Abadesso and Serra [14] published their work on 32 cases of biceps augmentation for improving the cosmetic appearance of the arms. They used calf implants in the submuscular plane to achieve the desired augmentation. Although the majority of their cases were performed for biceps augmentation, the authors do note that they were able to achieve a triceps augmentation in one patient who very much liked the aesthetics of his biceps augmentation. Using two stacked calf implants secured by a 3-0 nylon suture as they did for biceps augmentation, the authors placed this stacked set of implants beneath the triceps muscle to achieve a triceps augmentation. The incision used is the same one described for their biceps augmentation, namely, an S-shaped incision in the midarm region over the intermuscular septum.

Indications

Initially, triceps augmentation was introduced as a means to treating asymmetries in the arm region left due to congenital anomalies and trauma producing atrophy of muscles in the upper extremity and in those patients who suffered volume deficits secondary to trauma or post-oncologic surgery. Triceps augmentation, for purely aesthetic reasons, is indicated for the patient who has hypoplasia in the area of the triceps muscle. It can be used in the patient who has a condition from birth resulting in hypoplasia or may be applied to a patient who is unsuccessful in achieving the desired volume in the region of the triceps, despite aggressive weight training (e.g., bodybuilders).

Contraindications

While not every male presenting for triceps augmentation suffers from muscle dysmorphia/body dysmorphic disorder, the surgeon must be aware of this and take it into consideration when considering a patient for muscle augmentation surgery. A patient who seems unrealistic in the goals of his surgery should be turned away.

Limitations

In any initial triceps augmentation, patients are instructed on the fact that they can achieve an augmentation of approximately 1 inch in added circumference of the arm. Larger augmentations may require a second operation with larger, custom implants. Also, patients are instructed that while biceps and triceps augmentations can be performed, it is safer to separate this into two separate surgeries to avoid the risk of compartment syndrome in the upper extremity.

Relevant Anatomy

The technique described herein is ideal in that it avoids major neurovascular structures in the upper extremity. The posterior compartment of the arm is relatively devoid of major structures in the superficial planes. However, for completeness sake we will review some of the basic anatomy that is pertinent to the discussion of triceps augmentation.

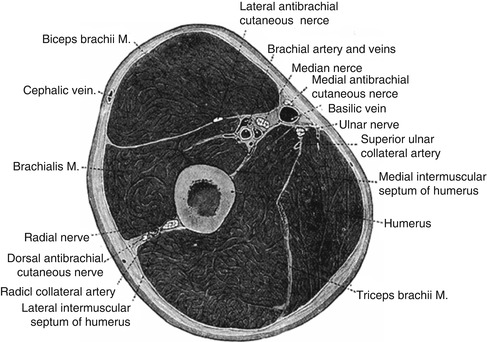

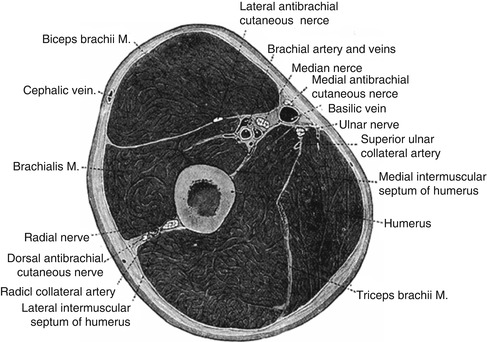

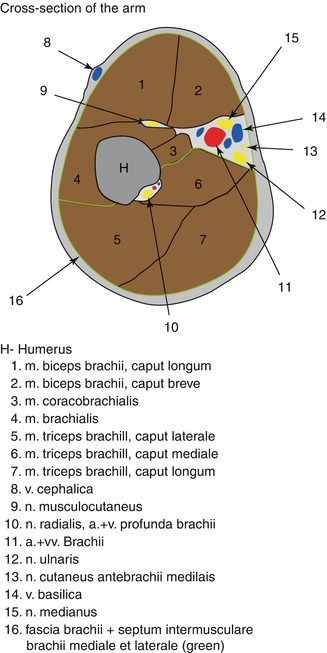

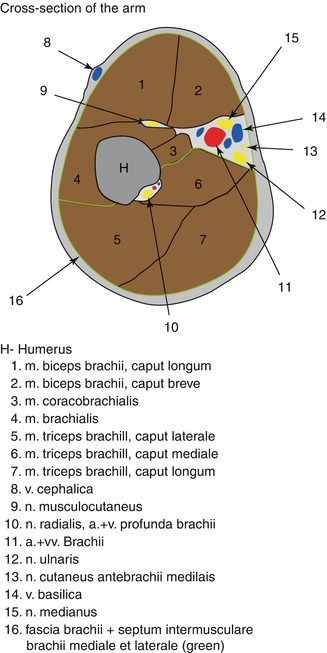

An axial section through the midarm shows much of the relevant anatomy for triceps augmentation (Fig. 4.1). Two distinct muscular compartments (anterior and posterior) exist and are separated by the medial and lateral intermuscular septa and humerus [15]. The medial and lateral intermuscular septa arise from the humerus and insert into the brachial fascia, which covers the superficial muscles of the anterior compartment. The anterior compartment is composed of the biceps brachii, brachialis, and coracobrachialis.

Fig. 4.1

Axial cross section of the arm showing the humerus with medial and lateral intermuscular septa that separate anterior from posterior compartments of the arm. The anterior compartment is composed of the biceps brachii, brachialis, and coracobrachialis. The posterior compartment is composed of the triceps muscle. Major neurovascular structures are primarily localized to the medial aspect of the arm

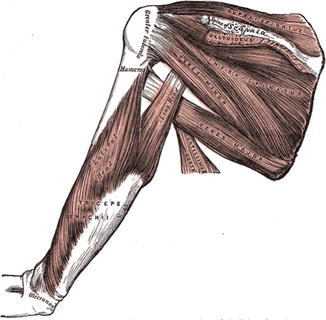

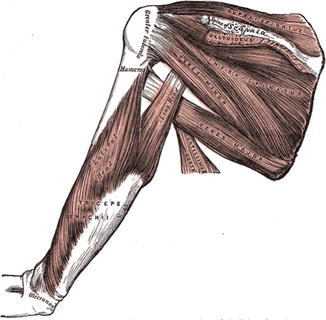

The posterior compartment, also covered by extensions of the intermuscular septa, is comprised of the triceps muscle, which acts in extension of the forearm. The triceps brachii is composed of three heads (Fig. 4.2). The long head arises by a flattened tendon from the infraglenoid tuberosity of the scapula. The lateral head arises from the posterior surface of the body of the humerus. The medial head arises from the posterior surface of the body of the humerus, below the groove for the radial nerve. The three heads then converge into one triceps tendon which begins about the middle of the muscle and inserts into the posterior portion of the olecranon of the ulna. Most superficial of these three heads is the long head of the triceps. Also in a very superficial position, but more laterally, is the lateral head of the triceps muscle. The medial head is found deeper, adjacent to the medial aspect of the humerus.

Fig. 4.2

Diagram depicting the triceps muscle, focusing on the lateral and long heads of the triceps which are most superficial and pertinent to the dissection for triceps augmentation. The medial head of the triceps is not visualized

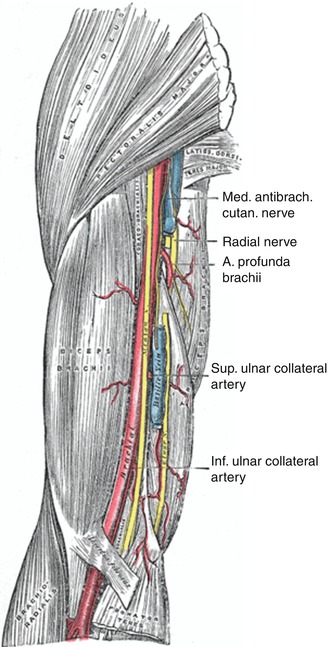

The major neurovascular structures of the arm are located in an extracompartmental location on the medial aspect of the arm (Fig. 4.3). The basilic vein plays a major role in the superficial venous drainage of the upper extremity. It runs upward along the medial border of the biceps brachii; perforates the deep fascia slightly below the middle of the arm; and, ascending on the medial side of the brachial artery to the lower border of the teres major, continues onward as the axillary vein. The brachial artery (a continuation of the axillary artery) commences at the lower margin of the tendon of the teres major and, passing down the arm, ends about 1 cm below the bend of the elbow, where it divides into the radial and ulnar arteries. At first, the brachial artery lies medial to the humerus; however, it gradually moves in front of the bone as it runs down the arm, and at the bend of the elbow, it lies midway between its two epicondyles. The brachial artery is the major supplier of blood flow to the upper extremities. Because this artery is superficial throughout its entire extent, being covered in front by the integument and the superficial and deep fascia, great care should be taken to preserve its integrity. The ulnar nerve is similarly located in this medial extracompartmental location. It arises from the medial cord of the brachial plexus and descends on the posteromedial aspect of the humerus. The nerve supplies motor function to the forearm and hand. It is only with extensive submuscular dissection that any of these major neurovascular structures can be encountered as they are removed from the proposed planes of dissection for triceps augmentation, particularly when performed in the subfascial position.

Fig. 4.3

Major neurovascular structures located in medial aspect of the arm in the extracompartmental space

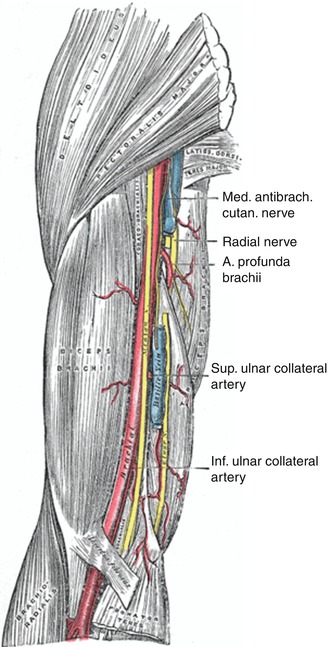

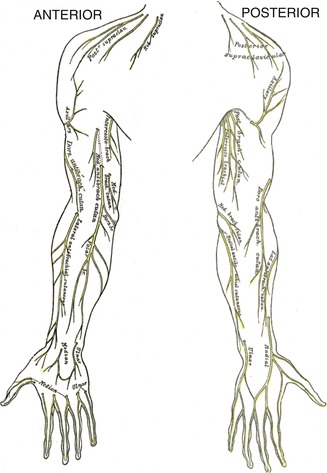

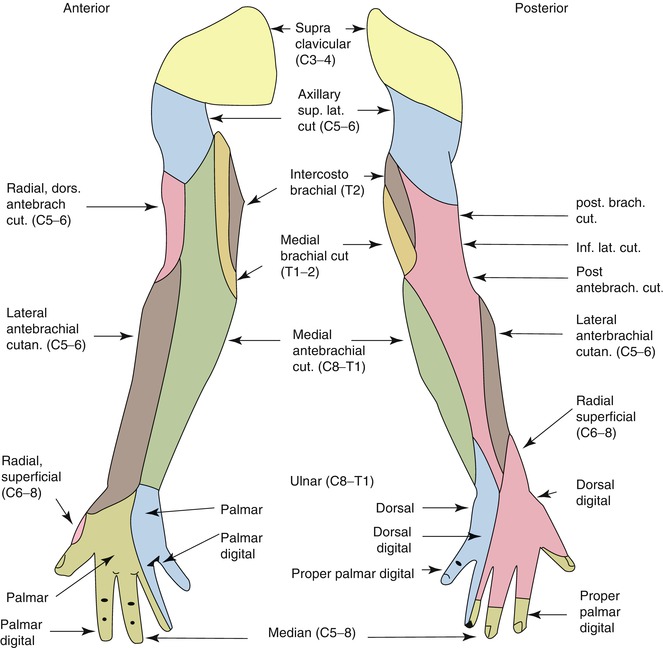

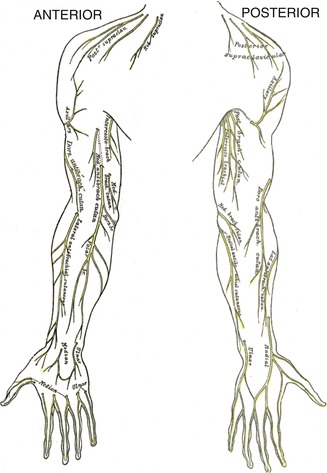

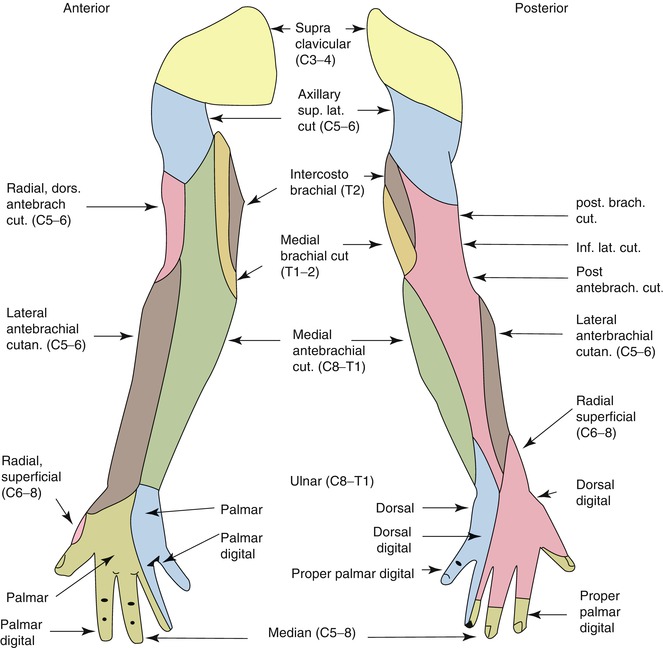

When considering triceps augmentation, structures that are significantly at risk of injury are the radial nerve and two of its smaller cutaneous branches, the posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm (posterior brachial cutaneous nerve) and the dorsal antebrachial cutaneous nerve (posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm) (Fig. 4.4). The radial nerve occupies a position deep within the posterior compartment in close proximity to the posterior aspect of the humerus and medial head of the triceps, approximately 97–142 mm distal to the acromion [15, 16] (Fig. 4.5). The radial nerve is responsible for the innervation of the triceps and arises from the seventh and eighth cranial nerves. It is really only of note in patients receiving submuscular placement of the triceps implant. In this case, overaggressive dissection near the humerus may put the radial nerve at risk of injury. Immediately adjacent to the radial nerve course some of its cutaneous branches, namely, the posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm and the dorsal antebrachial cutaneous nerve. The posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm provides sensory innervation for much of the skin on the back of the arm (Fig. 4.6). The dorsal antebrachial cutaneous nerve, also a branch of the radial, provides sensation to the posterior aspect of the forearm. Typically the cutaneous branches are at greater risk as they are smaller and more fragile nerves. Injuries, when encountered, are the result of traction injury rather than transection. Traction injuries result in a temporary neurapraxia with loss of sensation in the posterior arm (posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm) or the forearm (dorsal antebrachial cutaneous nerve). Generally these nerves are avoided in the dissection of the subfascial plane and are really only at risk in submuscular augmentation cases.

Fig. 4.4

Major sensory nerves of the arm and their distribution

Fig. 4.5

Radial nerve in its position deep within the arm and giving off two of its major cutaneous branches at risk for injury in triceps augmentation: posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm and the dorsal antebrachial cutaneous nerve

Fig. 4.6

Dermatomes of major sensory nerves of the arm

Consultation/Implant Selection

The consultation begins with a thorough medical history of the patient. Special attention is taken to ask specifically about trauma to the extremity, history of vascular insufficiency which may put blood flow at risk, history of venous insufficiency or arm swelling, and any history of nerve damage or sensory deficits as may be seen in patients with diabetes mellitus. Also, patients with histories of nerve entrapment disorders should be asked about the current state of those nerves and any long-term sequelae. At the time of consultation, the patient is asked what specifically about their arm bothers them as it may be necessary to combine muscle augmentation surgery with adjunct procedures such as liposculpture or brachioplasty to achieve the patient’s goals. Preoperative goals are assessed at this point. A patient who has unrealistic expectations and is unable to comply with the strict postoperative instructions is deemed a poor candidate for augmentation. Patients who have congenital anomalies, a significant size disparity between the two arms, or bilateral hypoplasia are informed that several surgeries may be required to attain symmetry and achieve the augmentation they desire. Patients are also asked about their current level of activity and muscle building history, taking care to inform the patient of the need to take at least 1 month of time to recover before resuming any vigorous arm building regimens.

After completion of the history, the patient’s arms are evaluated. First, symmetry of the two sides is assessed and any disparity is brought to the attention of the patient. Although the majority of patients present with a preexisting asymmetry of the arms, not many patients note the difference, and this can be a source of medicolegal matters in the future. The physician then evaluates the quality of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle. A person who has very thin tissues or significant hypoplasia of the triceps may not be able to adequately accommodate a large implant. Also, a person with thin tissues may have to be counseled about the possible need for a submuscular placement of the prosthesis. This should be accompanied by a discussion of the increased risks associated with triceps augmentation in the submuscular plane.

Next, the patient’s arms are measured in circumference at the midportion of the arm, with the patient in flexed and neutral positions. These measurements are primarily used in the postoperative period to demonstrate the results of augmentation. Another measurement is taken with the patient flexing their triceps muscle. The proximal point of the muscle belly is palpated and marked as is the distal portion of the muscle belly and this is measured. Having this second measurement allows one to assess the maximum length of implant that can be accommodated in the triceps region. The width of the muscle belly is measured from its medial to lateral extent while the patient’s muscle is flexed. Based on these latter measurements, the surgeon can choose the implant that would best suit the patient’s body habitus.

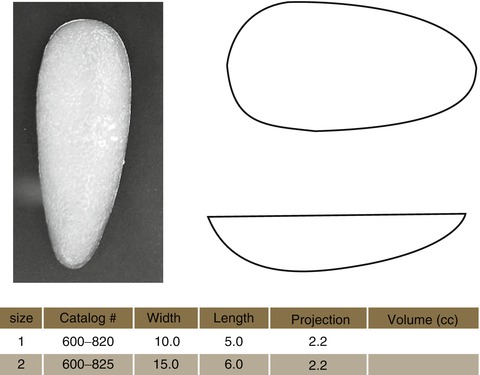

Available Implants (Table 4.1)

Table 4.1

Triceps implants (Aesthetic and Reconstructive Technologies, Inc., Reno, NV)

Preoperative Planning and Marking

The triceps contour is marked out with a surgical marking pen, taking special care to also mark the apex of the triceps on contraction as the implant must be centered under this point. A marking is then made in the axillary region for the initial incision in the axilla.

Operative Technique

The patient is brought to the operating room, prepped, and draped in the usual supine position with the arms extended. A 3–4 cm incision is made in the axillary region with a number 15 blade scalpel (Fig. 4.7). The skin is elevated by sharp using Metzenbaum scissors and blunt finger dissection (Fig. 4.8). The fascia overlying the long head of the triceps muscle is identified. Next, an incision is made in the fascia with a number 15 blade scalpel in the direction of the muscle fibers (Fig. 4.9). The long head of the triceps is then visualized (Fig. 4.10). Stay sutures are then placed into the muscle fascia to aid in closure at the end of the procedure (Fig. 4.11). If the patient is to have placement of the implant below the triceps muscle, it is at this point that the long head of the triceps is split with a hemostat in line with its fibers. A submuscular plane can then be developed below the long head of the triceps muscle primarily, but also below the lateral head. This plane seats the implant squarely on the humerus. The authors’ preference is to create a subfascial pocket for implant placement. Blunt dissection is performed using the operator’s digit underneath the fascia overlying the long head of the triceps muscle. Once the pocket dissection is well underway, a spatula dissector is placed underneath the fascia, and the dissection of the pocket is completed (Fig. 4.12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree