8 Liver transplantation

Introduction

The single most effective therapy for end-stage liver failure (ESLF) is liver transplantation (LT). Data from the European Liver Transplant Registry show that over 70 000 LT transplants have been performed in 137 participating centres around Europe.1 Currently 680 liver transplants are performed yearly in the UK for end-stage liver disease (ESLD) and to date more than 6000 patients have been transplanted. Nationally, in 2007, over 1000 patients were listed for LT, with a mean waiting time of 60 days. Unfortunately the supply cannot meet demand. A recent audit of the seven LT centres in the UK suggested that up to 14% of patients listed will die waiting,2,3 while in the USA more than 1500 patients per annum (from a waiting list of over 17 000 patients) will die waiting for a transplant.4

Indications

In the UK in 1999, following the death of a young woman with liver failure who was not listed for LT, a colloquium was set up to discuss ethical issues and guidelines for appropriate patient selection. It was agreed that donated livers should be considered a national resource and that patients should be considered for LT if they had an anticipated length of life (in the absence of LT) of less than 1 year or an unacceptable quality of life, providing patients had a 50% chance of being alive at 5 years after transplant. For many conditions there are guidelines and algorithms to help the clinician decide whether a patient meets certain acceptable criteria. Guidelines for LT also reflect the reality of the donor pool, aiming to maximise benefit from this scarce resource. It is imperative that these guidelines are not set in stone and are undergoing a constant process of refinement to meet the changing need.5,6

Patients may present with minimal symptoms or at the extreme have an accumulation of complications such as varices, ascites, infection Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP or cholangitis) combined with poor synthetic liver function, e.g. hypoalbuminaemia (<30 g/L), hyperbilirubinaemia (>50 μmol/L) and prolonged clotting times (prothrombin time prolonged over control). Once infection ensues patients with ESLF have a 50% chance of dying within 6 months. The common indications for LT differ between adults (Box 8.1) and children (Box 8.2), although some do overlap. To date, over 60 conditions have been treated by LT.

Box 8.1 Indications for LT (adults)

Box 8.2 Commoner indications for LT in children

Familial cholestasis syndromes

Unresectable tumours, e.g. hepatoblastomas

Acute liver failure – viral, drugs (e.g. paracetamol toxicity, autoimmune)

Alcohol

The most controversial indication for adults in the UK is alcoholic liver disease (ALD). There have been recent concerns that the results of LT are poor for patients who return to alcohol. Patients suffering from ALD have to demonstrate a period of 6 months abstinence. This will allow the treating clinician time to assess the need for LT as well as assess the potential for recidivism. Unfortunately up to 25–50% will return to alcohol after LT, but only 10–15% of these patients will relapse to harmful drinking.7,8 Current graft survival rates are 72% at 5 years and compare well with other chronic liver diseases after LT.9 A working party has recently published guidelines for assessing patients with ALD and listing them for LT (Box 8.3).10,11

Box 8.3 Recommendations for alcohol-related liver disease

From Bathgate AJ on behalf of the UK Liver Transplant Units. Recommendations for alcohol-related liver disease. Lancet 2006; 367:2045–6. With permission from Elsevier.

Contraindications

More than two episodes of medical non-adherence

Return to drinking after full professional assessment

Hepatitis C (HCV)

The commonest indication for LT in the USA and Europe is HCV and it is predicted that HCV will place a major strain on future waiting lists. One of the problems in this cohort is recurrence of disease in almost all recipients. This can either occur in an accelerated form or insidiously, resulting in gradual graft fibrosis and dysfunction. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that recurrence can be worse after live-donor LT (LDLT)12 but with reduced ischaemic time in LDLT, theoretically, these donor grafts should actually do better. The universal recurrence of HCV in the graft leads to chronic hepatitis in most patients, progressing to cirrhosis in 20–50% of patients after 5 years.13,14

Not all patients with HCV require LT; most with compensated cirrhosis can be managed with antiviral therapy. Pegalated interferon with ribavirin is the most common regimen but these change according to response rates.15 A recent study reports a survival benefit (74% vs. 63% after 7 years) in patients receiving antiviral therapy compared with those who do not. Most centres should expect to achieve 5-year survival rates in excess of 70%.16

After hepatectomy HCV RNA levels fall rapidly and then, after the first few days, start to climb, often exceeding pretransplant levels; in fact after 4 weeks the level may be 20 times increased. Even antiviral therapy that depletes the virus pretransplant cannot prevent recurrence in the early postoperative period17,18 and few patients can tolerate this therapy immediately prior to transplantation. What remains controversial are those factors associated with progression of fibrosis and how the disease can be modified, thus prolonging graft survival. No single factor but rather a combination of factors are likely to be involved.

The main factors associated with accelerated disease recurrence include high viral load pretransplant (>106 IU/mL) and/or early after transplantation (>107 IU/mL), older donors 40–50 years, prolonged ischaemia, cytomegalovirus (CMV) coinfection, over-immunosuppression, genotype 1b and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection.19

The main factors associated with accelerated disease recurrence include high viral load pretransplant (>106 IU/mL) and/or early after transplantation (>107 IU/mL), older donors 40–50 years, prolonged ischaemia, cytomegalovirus (CMV) coinfection, over-immunosuppression, genotype 1b and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection.19

It has been suggested that treatments should therefore focus more on minimising viral replication in the early postoperative period but no regimen has proven superiority and regimes can be too toxic so soon after LT.20,21 Better outcomes may be developed by tailoring protocols with specific immunosuppression. HCV genotype and HCV RNA do not appear to correlate with survival, but in the presence of alcohol abuse outcome is likely to be worse than with HCV alone.

Hepatitis B (HBV)

The situation for HBV is very different. Historically 80% of patients would develop recurrence but now antiviral therapy with nucleoside and nucleotide analogues (such as lamivudine) and HbIg provide excellent survival rates with low rates of reinfection.22,23 Adefovir is an alternative if patients develop resistance to lamivudine.24 Ten-year survival rates for HBV can be expected to be 70%.25 Unlike HCV, HBV may not be detectable even up to 2 years post-transplant in 90% of patients.26 HBV is also a common cause of fulminant hepatic failure (FHF), occurring in 4% of patients presenting with acute HBV infection.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

Patients with PSC are often managed expectantly. Some patients may require drainage procedures, either surgical or by stenting and some by medical means (e.g. antihistamines, cholestyramine, ursodeoxycholic acid or rifampacin). Nevertheless, for those progressing to ESLD, LT remains the only option; 70% will also have inflammatory bowel disease and this is predominantly ulcerative colitis. These patients are often a challenge to manage. For example, it would make sense to perform a colectomy before LT in anyone at high risk of developing a colonic malignancy.27,28

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and its treatment with LT, has been revisited in recent years. Aggressive surgical resection remains the treatment of choice whenever possible, but for a select group of patients with irresectable disease LT may be the only hope. There is no accurate method of differentiating a benign from a malignant stricture either biochemically or radiologically. A CA19.9 >100 U/mL has a sensitivity and specificity of over 80%; this can be improved to >90% if considered with a carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Peripheral intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or extrahepatic distal tumours do not cause so much of a diagnostic problem, but the ‘Klatskin’ or hilar tumours are more problematic as they often present late and involve major vascular structures at the hilum, making them unresectable. In the presence of chronic liver disease (e.g. PSC, fibrocystic disease) it would therefore appear logical to treat by LT, except the patient would then need to be immunosuppressed, which goes against current teaching. Early reports showed 5-year survival rates of 26%, with median survival generally less than 12 months.29 Many centres have reported their experiences over the last 5 years using various combinations of neoadjuvant and adjuvant regimens. A recent analysis from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database of over 280 patients over 18 years indicate 1- and 5-year survival rates of 74% and 38% respectively.30 Newer regimens with better survival have now been advocated. The Mayo Clinic have the largest experience using staging laparoscopy to exclude nodal disease combined with external beam irradiation, brachytherapy and treatment with fluorouracil (FU) and/or capcitabine. The most recent report (n = 64) suggests a 5-year patient and disease-free survival of 76% and 60% respectively.31 A CEA >100, older age, previous cholecystectomy, a mass on computed tomography (CT) scan, residual tumour >2 cm and tumour grade were independent risk factors for recurrence.31 A non-randomised retrospective comparison between resection and LT demonstrated superior survival for LT, 82% vs. 21%, with 13% vs. 27% for recurrence.32 The jury is still out as to whether cholangiocarcinoma should be treated by LT and only a randomised clinical trial (RCT) will give the answer, but this will be difficult to do given that there is a wide variation between surgeons as to what is deemed resectable.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

In 1967 one of the world’s first LTs was performed for HCC but the initial results for this indication were poor and in 1989 LT for HCC was considered a contraindication due to 5-year survival rates <40%.33 It is now well recognised that LT for HCC does have an important role in carefully selected patients, particularly those with less advanced disease.

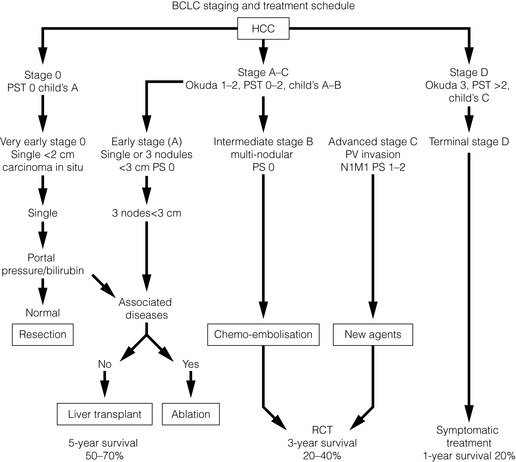

Staging of patients is very important and a number of staging systems exist. The ideal staging classification for HCC and LT should consider two factors: the extent of liver disease and tumour staging. The conventional TNM34 classification does not consider liver disease. Okuda35 staging includes tumour size, serum albumin, bilirubin and ascites. The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program36 (CLIP) is based on the Child–Pugh class,37,38 tumour progression, α-fetoprotein and presence of portal venous thrombosis. The CLIP was thought to be the most accurate in terms of prognosis,39 but now other systems are in place such as the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) Staging System.40 This classification uses variables such as tumour stage, liver function, physical status and cancer-related symptoms, and links these in a widely used treatment algorithm (Fig. 8.1). Patients with stage A disease are usually suitable candidates for LT.

Figure 8.1 Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging classification and treatment schedule.40 Stage 0: very early HCC suitable for resection. Stage A: early HCC suitable for more radical treatment such as resection, liver transplant or ablation. Stage B: patients with intermediate HCC may benefit from chemoembolisation. Stage C: patients with advanced HCC may receive new agents in the setting of an RCT. Stage D: advanced disease suitable for only palliative/symptomatic treatment.

With kind permission from Springer Science & Business Media: Journal of Gastroenterology, Llovet JM. Updated treatment approach to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol 2005; 40:225-35.

Pioneering work from Milan, Italy revisited the idea of LT for HCC.41 Those patients with cirrhosis (Child’s B or C) with a single tumour <5 cm or up to three tumours <3 cm, in the absence of macrovascular portal vein invasion, showed 5-year survival rates of 70% with only a 15% recurrence rate. Although these ‘Milan criteria’ were used widely for definition of acceptability onto the liver transplant list, it is now argued that the Milan criteria do not consider patients who have larger tumours with more favourable histology (such as well-differentiated tumours with no vascular invasion). At least 30% of patients who meet Milan criteria will have poorly differentiated tumours with vascular invasion and a poorer survival. Others suggest that expanding criteria does not adversely affect outcome.42 The most widely quoted expanded criteria are from University of California San Francisco (UCSF)42 (single tumour <6.5 cm, maximum of three total tumours with none greater than >4.5 cm and cumulative tumour size <8 cm). When applied to a large series of patients the results are marginally worse than those reported for Milan criteria (64% vs. 79% survival at 5 years).43

Another difficulty is that radiological staging does not equal histological staging. Consequently, patients meeting histological UCSF criteria have better 5-year survival than those meeting radiological UCSF criteria.44 A recent report of 168 patients by Yao et al. suggests that a 5-year recurrence-free probability of 59% can be achieved in those with explants exceeding UCSF criteria. This compares to 96.7% for those within UCSF criteria.45. In the UK, HCC patients have to fulfil category 2 listing criteria. A lesion has to be present in the same location on at least two radiological imaging modalities (either ultrasound, triple phase CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or hepatic angiogram) and has to fulfil Milan criteria. The widest diameter on CT is the maximum recorded diameter.5,46

Since the UK HCC consensus meeting in March 2008, there has been agreement that solitary lesions between 5 and 7cm with <20% progression over 6 months will be elligible for consideration of LT. The outcome of LT for HCC after bridging treatments such as resection, transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) or radiofrequency ablation has also been reviewed recently.47,48 Some studies suggest that a good response to TACE can predict survival at 5 years when compared to those tumours that do not respond at all (85% vs. 51%). This has not been translated into showing a benefit in reducing dropout rates for those exceeding listing criteria.49 Indeed, bridging therapies on the whole have shown no benefit in reducing dropout rates for those that exceed listing criteria. Controversy is likely to continue to surround LT for HCC, particularly in the setting of LDLT, when potential recipients may exceed conventional listing criteria by virtue of supplying their own donor.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

The survival of patients infected with HIV has improved dramatically in recent years because of advances in highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Until recently, HIV-positive patients were almost universally considered to be an absolute contraindication to transplantation. Early reports of LT in HIV-infected individuals showed poor results. Pittsburgh were the first to report their experience with 25 patients.50 Failure in the early 1990s was due to poorer patient selection, lack of potent immunosuppression and availability of good antiviral regimens. It also appears that HCV coinfection with HIV has a significant impact on survival, with poor outcome compared to HBV coinfection.51 This is especially important given that rates of coinfection of HIV and hepatitis B or C is 5–10% in the UK.

Guidelines52 and recent reviews53 of LT in HIV-infected individuals have recently been published. Current practice targets those with a low HIV viral load with limited or treated opportunistic infections and a CD4+ T-cell count >200/mL or >100/μL in the presence of portal hypertension.54

A recent analysis from the THEVIC study group showed that with use of newer antiviral agents 5-year survival is 51% in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection compared with 81% in those with HCV alone.55 A National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded multicentre trial has been initiated to evaluate further treatment outcomes.

Hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS)

HPS is a pulmonary complication observed in patients who have chronic liver disease and/or portal hypertension. This is due to intrapulmonary vascular dilatation causing severe hypoxaemia. HPS is usually detected when patients are being preassessed for listing. A diagnosis is made by blood gas analysis, transthoracic contrast-enhanced echo or a body scan with 99 mTc-labelled macroaggregated albumin perfusion. When the PaO2 is ≥80 mmHg it is unlikely that the patient has HPS. When it is less than this imaging should be tailored to demonstrate pulmonary vascular dilatation. Knowing the degree of hypoxaemia is crucial to optimising patient management. Severely hypoxaemic patients (e.g. PaO2 < 60 mmHg) should be listed for LT; less than 50 mmHg may preclude LT because mortality is greatly increased. Between 60 and 80 mmHg, patients should be carefully followed to note any deterioration.56

Patient selection, risk assessment and allocation

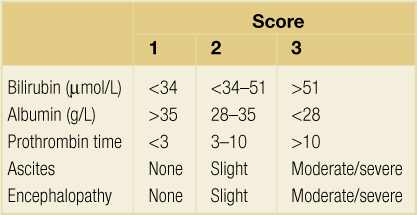

Survival and outcome depends on the patient’s clinical status and whether the LT is performed semi-electively or as an emergency for those with ALF. Traditionally cirrhotic patients are assessed in terms of their Child–Pugh score (CTP)37,38 (Table 8.1). This score was devised to predict outcome in patients with portal hypertension and not those awaiting LT. Nevertheless, patients who are Child’s A can remain stable for a considerable length of time without decompensation or the need for LT. Of those classified as Child’s B/C, 75% will eventually meet criteria for LT. The limitations of CTP relate to sick Child’s C patients. In particular it fails to discriminate those with FHF and does not take into account renal function, which is an important predictor of outcome. As a result the King’s College Hospital criteria were widely adopted in the UK to define poor prognosis groups requiring LT with FHF57 (Box 8.4).

Box 8.4 King’s criteria for LT in fulminant hepatic failure

From O’Grady JG, Alexander GJ, Hayllar KM et al. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology 1989; 97:439–45. With permission from Elsevier/AGA Institute.

More recently, because of concerns over priority for organ allocation, the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD; Box 8.5) was developed in the USA.58 The MELD score does have limitations but it is not within the scope of this chapter to discuss all its pitfalls, which have been reviewed in detail elsewhere.59,60 It is estimated that it does not accurately predict mortality in up to 20% of patients based on concordance (c-statistic).61 For example, the MELD score is limited by not considering other important factors which influence outcome such as the use of marginal grafts (e.g. older donors, presence of steatosis, tumour histology, etc.).

Box 8.5 The Model for End-stage Liver Disease

From Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2001; 33:464–70. With permission from John Wiley & Sons/American Society for the Study of Liver Diseases.

MELD was originally developed to assess the prognosis of cirrhotic patients’ prognosis who underwent a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure (TIPS) and had been shown to predict short-term outcome in patients awaiting LT. Patients are given a score of severity, the higher the score the higher the risk of death.

MELD is good at predicting mortality within the first 3 months of LT for patients with many different aetiologies awaiting LT.62 More importantly, in the USA, the use of MELD to aid allocation of livers has reduced waiting time and waiting-list deaths by allowing the sicker patients to be transplanted.63–65

MELD is good at predicting mortality within the first 3 months of LT for patients with many different aetiologies awaiting LT.62 More importantly, in the USA, the use of MELD to aid allocation of livers has reduced waiting time and waiting-list deaths by allowing the sicker patients to be transplanted.63–65

To date MELD has undergone several revisions by the UNOS to allow better equity of access to donor livers – for example, capping of serum creatinine so those patients with renal failure do not have the advantage of a higher overall score. Another problem that was encountered was for patients with HCC. Those with long waiting times had a 50% chance of not meeting criteria at the time of LT because of tumour progression. Therefore UNOS modified the MELD score for HCC patients by loading the final score with additional points; this was originally 29. However, this score was deemed too high and the current UNOS policy is for patients with stage 2 disease (single tumour 2–5 cm or 2–3 nodules <3 cm) to receive 24 points and stage 1 patients no longer have any loading of points.66 The score is also capped to limit futile transplants for a score higher than 40.60

Other specific recipient risk factors for LT include advancing age (>65 years), but there is no upper age limit so long as the patient has a predicted survival of more than 50% at 5 years. Other adverse factors include obesity (body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2) and coronary artery disease, which should be treated before transplant if possible. Patients with advanced cardiac disease, poor ventricular function or cardiomyopathy are not candidates for LT. Many patients have transient and reversible renal failure (e.g. hepatorenal syndrome), which is not a contraindication for LT. Some patients will have reversible renal dysfunction and therefore may have combined liver and kidney transplants prematurely. Indeed, the number of combined transplants has increased during the MELD era. A general view is that those who have renal dysfunction but who are not dialysis dependent should not have a combined transplant, as suggested in recent guidelines.67

As the MELD score has limitations, the UK has developed its own scoring system to guide allocation (Box 8.6) and predict waiting-list mortality.68 This is called the UK Model (UK Model for End-stage Liver Disease, or UKELD). This is a modified MELD system incorporating serum sodium, which has been shown to be an independent predictor of death after LT.69 A UKELD score of 49 predicts a greater than 9% mortality at 1 year and is the minimum entry criterion to the waiting list.5

In the UK there are seven designated centres for LT and a recent working party has published new criteria for selection and de-listing for adult LT.5 The principles of selection and listing are summarised in Box 8.7. Listing and allocation for those patients with ALF is very different and these patients can be offered a donor liver from any region in the UK and take national priority. The waiting list is prioritised based on time spent on the list and exclusions are made by blood group compatibility and donor/recipient size. Criteria for registration as a super-urgent LT in the UK are summarised in Box 8.8.

Box 8.7 The principles of patient selection

From Neuberger J, Gimson A, Davies M et al. Selection of patients for liver transplantation and allocation of donated livers in the UK. Gut 2008; 57:252–7. With permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Box 8.8 Current UK criteria for registration as super-urgent

From Neuberger J, Gimson A, Davies M et al. Selection of patients for liver transplantation and allocation of donated livers in the UK. Gut 2008; 57:252–7. With permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Category 1

Aetiology: paracetamol poisoning – pH <7.25 more than 24 h after overdose and fluid resuscitation

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ICP, intracranial pressure; INR, international normalised ratio.

For elective registration all patients must fit into one of three categories:

Box 8.9 Variant syndromes and definitions for elective LT listing

LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.From Neuberger J, Gimson A, Davies M et al. Selection of patients for liver transplantation and allocation of donated livers in the UK. Gut 2008; 57:252–7. With permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Primary hyperlipidaemias

Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia with absent LDL receptor expression and LDL gene mutation

With the increasing number of waiting-list deaths and reduction in organ donors a number of innovative strategies have been developed to overcome this shortfall. The main developments have been the use of marginal donors (older age, steatotic livers and non-heart-beating donors), reduction hepatectomy or split-liver transplantation.70 Split-liver transplantation has had such a dramatic effect that it has reduced paediatric waiting-list mortality to almost zero,71 but regrettably this has not advanced the adult situation despite some use of the residual right lobe into adult recipients. In recent years this has provided a compelling argument to develop the ultimate application of split-liver transplantation, living-related liver transplantation (LRLT).72 In certain situations patients should be assessed for LT not just for aetiology but also for types of transplant, particularly if a living donor is available. LDLT has several advantages over cadaver liver transplantation. It reduces waiting-list mortality73 and increases the rate of transplantation, but can also offer the potential for pre-emptive transplantation before patients develop the serious complications associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, thus making liver transplantation more cost-effective.

Work-up for liver transplantation

Assessment for living donation

Although the first successful LDLT was done nearly 20 years ago, this still remains a controversial and complex area. The ethics of LDLT do not differ from those relating to renal transplantation. Donors must accept the risks of surgery and should agree to donation voluntarily without coercion. However, the stakes are higher for both donor and recipient. The only benefit to the donor is psychological. It is imperative to leave sufficient remnant liver to avoid hepatic insufficiency in the donor and provide a graft of sufficient size for restoration of health in the recipient. The ethical issues surrounding donation have been rigorously reviewed in detail elsewhere and it is well recognised that the risk is more appreciable than for renal transplantation (0.5% vs. 0.03%).74–76 There have been possibly 33 reported donor deaths,77,78 although the precise number is speculative as most probably go unreported.77–79 A recent population study suggests that donors would accept LDLT even with a 10% mortality risk.80

The majority of donor/recipient combinations have been ABO compatible, but not exclusively.81 ABO-incompatible recipients generally have worse outcomes.82 Unfortunately, at least 50% of potential recipients are unable to find a suitable donor. Furthermore, 10% of donors discover they have significant medical comorbidity that needs investigation.83 In total, less than 40% make suitable donors,84 making the cost of donor work-up significant.

In the USA, obesity is becoming an increasingly frequent contraindication to LDLT, as there is an appreciable risk of the donor liver having significant steatosis. For example, patients with a BMI >28 cm/kg2 have a 78% chance of more than 10% steatosis,85 although this has been disputed by others.86 It is well documented that steatosis increases the probability of compromised graft function and reduces hepatic regenerative capacity.87 Some centres therefore assess the degree of steatosis with a predonation biopsy despite the risks for the donor (0.4–1%). In a recent survey of LDLT practice only 15% of centres biopsied routinely, whereas 25% did not biopsy at all.88 A less invasive approach is to quantify steatosis with imaging, either CT or MRI (see below), but both these modalities have poor specificity.89

Hepatitis B surface antigen-positive donors are usually excluded from donation. Hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors can be used on the proviso they are also HepBsAg negative. In Taiwan up to 80% of the population can be hepatitis B core antibody positive. These donors should have a biopsy in order to exclude cirrhosis and fibrosis. Fortunately, donor hepatectomy in these patients has been shown to have no additional risk.90 The use of lamivudine and hepatitis B Ig can significantly minimise the acquisition or reactivation of hepatitis B in the recipient, even in living donation.91 LDLT in patients with HCV has been reviewed elsewhere.92,93 In summary, anti-HCV-positive donors are refused donation in most European countries, but in the USA HCV donors can donate to HCV recipients.Preliminary concerns that HCV recurrence is more severe compared to cadaver liver transplantation have not been substantiated.94,95

Imaging for LDLT and graft selection

New generation multislice helical CT and 3-D reconstructions are used for volumetry analysis and to identify important anatomical variants.96–98 Computerised analysis has been shown to correlate well with functional hepatic mass.99–100

MRI also provides acceptable high-resolution imaging without the added risk of radiation and contrast exposure when compared to CT.101–103

MRI also provides acceptable high-resolution imaging without the added risk of radiation and contrast exposure when compared to CT.101–103

Determining the correct size of the graft for LDLT is vital. For adults donor/recipients have to be well matched in terms of BMI. In most cases, when the body weight of the recipient is 30% more than the donor, it is unlikely that the donor operation will yield a graft of sufficient size and leave an adequate remnant. Different formulae have been devised for guidance when assessing graft size. To predict a safe remnant volume the graft is expressed as a percentage of the standard liver volume (SLV).104 It is generally agreed that between 30% and 40% SLV is sufficient to be safe.105 Another important issue which can be overlooked is that most formulae do not assess functional volume as it is very difficult to assess, particularly if the donor has a degree of steatosis or fibrosis. Graft/recipient body weight ratio (GRWR) of more than 0.8–1.0% (i.e. graft weight vs. body weight) is also used.106 If recipients are graded Child’s B or C then a GRWR of more than 0.85% will be required to avoid small-for-size syndrome.107

Techniques of liver transplantation

Although there is still no universal agreement the problems associated with UW are hyperkalaemic cardiac arrest, high viscosity, ischaemic-type biliary complications, microcirculatory disturbances due to undissolved particles and it is expensive. Celsior is cheaper, and has low potassium concentration with no need to flush before re-perfusion, no microparticles and improved biliary protection.108

Although there is still no universal agreement the problems associated with UW are hyperkalaemic cardiac arrest, high viscosity, ischaemic-type biliary complications, microcirculatory disturbances due to undissolved particles and it is expensive. Celsior is cheaper, and has low potassium concentration with no need to flush before re-perfusion, no microparticles and improved biliary protection.108

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree