11 Cardiothoracic transplantation

Introduction

Within 40 years heart transplantation has evolved from an experimental procedure to an effective therapeutic strategy for end-stage heart disease. In the current era heart transplant programmes around the world are showing medium-term survival in excess of 80–85%.1 Significant improvements have been achieved, particularly for 30-day and 1-year mortality. Nevertheless, the success of heart transplantation has raised expectations that under present circumstances it cannot fulfil. On one hand, due to improved management of ischaemic heart disease and increased longevity, the number of patients with heart failure is growing.2 On the other hand, there is a decrease in the number of cardiac transplantations due to donor organ constraints. This disparity between the number of donors and potential recipients has stimulated research to find new alternatives to transplantation. However, these so far had little impact on the current practice of heart transplantation. The advent of novel therapeutics and surgical options for impaired ventricles may in selected patients defer consideration for transplantation, and clinical guidelines have been provided for this purpose.3 The contemporary practice of heart transplantation with respect to indications, surgical techniques and donor and recipient management will now be reviewed.

Indications for heart transplantation

The reason for undertaking heart transplantation is to prolong life and to improve its quality. The indications for adult heart transplantation have remained essentially unchanged over the last three decades and at present are predominantly coronary-related heart failure (38%) and cardiomyopathies (45%). Valvular (2%) and miscellaneous diagnoses (10%), adult congenital (3%) and re-transplantation (2%) constitute the rest.1

Aetiology of heart disease

Introduction

End-stage heart failure has become a major medical problem.4 The increasing prevalence with rising age of the general population in most societies accounts for a large proportion of healthcare spending due to frequent hospital admissions.5 In the aetiology of congestive heart failure (CHF), we differentiate primarily ischaemic from other cardiomyopathies and congenital heart disease during transplant candidate assessment.

Ischaemic heart disease

This constitutes the largest group requiring heart transplantation. These patients can present in a variety of ways, from being acutely ill after myocardial infarction on mechanical support to being chronically ill with heart failure with or without previous surgical or catheter-based intervention. Unfortunately there are no conclusive prospective studies comparing conventional treatment methods with heart transplantation to provide guidance in risk–benefit assessment. A digest of current thinking would indicate that heart transplantation would definitely be indicated in a patient with severe heart failure with poor ventricular function (ejection fraction <15%), symptoms of heart failure with little or no angina, diffuse coronary artery disease, absence of reversible ischaemia and/or poor right ventricular function (ejection fraction <35%). What is clear is that patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy who develop heart failure are likely to have a worse prognosis than non- ischaemic patients.6

Non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy

Certain types of cardiomyopathies can show reversibility, and a period of observation with medical treatment should be tried before listing. These include lymphocytic myocarditis, peripartum cardiomyopathy, hypertensive cardiomyopathy and alcoholic cardiomyopathy.7

Indications for paediatric patients are similar; however, the risk of death is highest during the first 3 months after presentation, therefore failure of aggressive medical treatment early in the course of the disease should lead to early assessment for transplantation. Acute myocarditis needs a special mention as the finding of acute inflammation on biopsy is a favourable prognostic sign for subsequent recovery.8

Recipient evaluation and selection

Patients are evaluated for transplantation once a referral has been made. We admit the patient for a few days for assessment. During this period there is a systematic evaluation of both the physical and psychological state of the patient; it also gives an opportunity to develop a rapport between the patient, relatives and the multidisciplinary team. The protocol used in our own centre for assessment is summarised in Box 11.1. The assessment process is designed to answer the following questions:

Box 11.1 Recipient assessment protocol for heart transplantation

Full history and physical examination. Investigations include:

Selection criteria

Mancini et al.8 and others9–11 showed that patients with a peak exercise oxygen consumption of <14 mL/kg/min had a significantly higher mortality than patients with a peak exercise oxygen consumption of >14 mL/kg/min.

Mancini et al.8 and others9–11 showed that patients with a peak exercise oxygen consumption of <14 mL/kg/min had a significantly higher mortality than patients with a peak exercise oxygen consumption of >14 mL/kg/min.

The limitation of this technique is that it can be influenced by body composition, individual motivation or general deconditioning. Some centres have incorporated the heart failure survival score (HFSS) to their preoperative assessment. The score consists of seven variables – resting heart rate, left ventricular ejection fraction, mean arterial blood pressure, interventricular conduction delay, peak exercise oxygen consumption (VO2), serum sodium and ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Using these variables Aaronson et al. developed a mathematical model to predict outcome with medical management.9 This score, along with maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) and clinical assessment, can bring some rigour to the selection process for transplantation.

Deng et al. showed that cardiac transplantation does not benefit patients with medium- and low-mortality risk as assessed by calculation of heart failure survival score.10

Deng et al. showed that cardiac transplantation does not benefit patients with medium- and low-mortality risk as assessed by calculation of heart failure survival score.10

More recent evidence suggests that for patients with ejection fraction <20% and severely reduced functional capacity, best outcomes are achieved in the absence of comorbidities that raise perioperative mortality risks. The predictors of survival have been refined and patients requiring inotropic or mechanical support to maintain systemic perfusion in advanced heart failure have a good prognosis with heart transplantation.1

Contraindications

Contraindications to heart transplantation are summarised in Box 11.2. These can be classed in three groups:

Box 11.2 Contraindications for heart transplant

Factors affecting long-term prognosis

Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of more than 6 Wood units has been considered an absolute contraindication to heart transplantation but with the introduction of nitric oxide, use of a bicaval anastomotic technique, early implantation of ventricular assist devices and increasing use of perioperative phosphodiesterase inhibitors and isoprenaline, good results can be obtained in patients who formerly would not have been offered the opportunity of transplantation. Nevertheless, the presence of an elevated PVR should not be taken lightly as the donor right ventricle generally tolerates a systolic pressure of more than 50 mmHg poorly and would acutely fail. In our own practice a PVR >3 Wood units would be considered a relative contraindication to transplantation. The transpulmonary gradient (TPG) (see Box 11.3) represents the pressure gradient across the pulmonary vascular bed and is independent of the pulmonary blood flow. Some consider the elevation of this above 14 mmHg as a more useful indication of significantly raised PVR as this is independent of the cardiac output, which may be poor in these patients. We rely more on this criterion and generally consider a fixed TPG of 12 mmHg and above as an absolute contraindication. In paediatric patients a higher TPG can be considered as it could be overcome with a larger sized donor heart. Heterotopic transplantation can also be considered in these circumstances to overcome elevated pulmonary vascular resistance.11

Box 11.3 Definitions

Pulmonary vascular resistance

PVR (Wood units) = [PA mean − pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCW)/CO]

Renal dysfunction is one of the most common problems encountered in the assessment of these patients. Multiple studies have shown that it is a major risk factor for mortality after heart transplantation. A common dilemma is to distinguish between renal dysfunction due to intrinsic renal disease or severe heart failure and aggressive diuretic therapy. It is essential to measure the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and a low GFR may occasionally indicate renal biopsy to further elucidate the cause. Others have used measurement of effective renal plasma flow (ERPF) as an investigative modality, and less than 200 mL/min is considered indicative of major intrinsic renal dysfunction and an indication for combined heart and kidney transplantation which can be peformed with good outcomes.12

Compliance is the neurobehavioural capacity to adhere to a complex lifelong medical regimen. Non-compliance following heart transplantation can lead to major morbidity or death. Unfortunately there are no proven psychological or sociological factors to predict poor compliance or adverse outcome after transplantation. Adherence to medical treatment and ability to keep appointments can provide some pointers towards compliance. Psychiatric disorders that impair compliance, such as severe depression or untreated schizophrenia, are contraindications to heart transplantation.13

Other options

It is not unusual to find patients who have been referred for transplantation to be suitable for alternative treatments. In addition there are newer methods of treatment of heart failure in both medical and surgical disciplines being developed, and some of these patients could derive benefit from them.14 Some developments are worth mentioning.

Biventricular pacing

In 20–30% of patients with symptomatic heart failure there is a prolonged PR interval, wide QRS complexes and intraventricular conduction disorders leading to a discoordinate contraction pattern. The result is earlier atrial contraction causing mitral regurgitation. This is further compromised by paradoxical septal motion due to wide QRS and conduction abnormalities. Biventricular pacing has been shown to synchronise contractility and improve the functional class of patients.15–17 We have used biventricular pacing in several of our patients with improvement in functional class and subsequent delisting from transplantation.

Implantable cardio defibrillators

Implantable defibrillators have had benefical impact on survival of patients with implantation including previous ventricular arrhythmias and poor ejection fraction status.18

Novel end-stage heart disease therapeutics

New agents to treat end-stage disease have become available and the benefit of antagonists to stabilise symptoms and delay patients entering waiting lists for transplantation has been evident. A recent landmark publication by the American College of Cardiology has confirmed the advanced administration of medical therapeutics in a large cohort of patients and specific guidelines have been widely implemented.19,20 Other novel therapeutics are in various stages of clinical trials.

Ventricular assist devices

Over approximately 15 years ventricular assist device support has developed into a realistic option for selected patients with refractory congestive heart failure of various aetiologies. This has been established in the REMATCH trial, where medical management of New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV heart failure patients was inferior to mechanical assistance when comparing 1- and 2-year survival.21,22 The limiting factors for this approach, either as a bridge to transplantation or as destination therapy, are availability and device selection. More recently the role of assist devices for right heart failure indications is evolving.

Donor selection and matching

Specific guidelines for optimal donor selection have been published by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation.23

Specific guidelines for optimal donor selection have been published by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation.23

Management of the potential organ donor has evolved and requires a multidisciplinary approach.24 Donor allocation for hearts in the UK is run by UK Transplant (UKT). The hearts are allocated on a pro rata basis; however, a category of ‘urgent’ was created in 1999 to deal with acutely ill patients. Once a donor is identified certain criteria apply before acceptance.

Donor age

An upper limit of 60 years is generally advocated and used by our own unit but there is variation in other centres. The current mean age including paediatric donors at our programme currently is 44 years. It is important that donor age should not be viewed in absolute terms but should be considered along with other factors such as cardiac function, recipient urgency and projected ischaemic times. However, older donors are more likely to have coronary artery disease and there is increased mortality for the recipient if the heart has come from a donor over 40 years of age.1 The presence of coronary artery disease should not be considered an absolute exclusion criterion as satisfactory outcomes can be achieved with concomitant coronary revascularisation.25 United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) data from the USA show that in 1982 2.1% of donors were aged 50 years or greater but by 1994 this percentage had increased to 8.9% and has remained the same over the last 10 years.26 It remains difficult to evaluate pre-existing donor coronary artery disease at the time of organ procurement. Some centres advocate a single plane coronary angiography (on table), but the availability and interpretation remain problematic.

Cardiac function

Brain death leads to myocardial changes with abnormalities seen on ECG of ST segment elevation, T-wave inversion and Q waves, often signifying subendocardial ischaemia. Events following brain death, namely prolonged hypotension, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and high-dose inotropic support also contribute to cardiac dysfunction, particularly acute right ventricular impairment. The assessment of cardiac function is undertaken by echocardiogram, Swan–Ganz catheter and finally by the surgeon procuring the organ. Troponin I may be useful in detecting donor myocardial injury and elevated levels are associated with impaired cardiac function.27

Size matching

As a general rule for routine adult heart transplantation with a normal PVR, 30% undersizing is acceptable, although much smaller donors have been reported with satisfactory outcome.28,29 In patients with a raised PVR deliberate oversizing is routinely undertaken to overcome pulmonary vascular resistance. In the paediatric group oversizing is often done to utilise all available hearts. In our last 30 consecutive paediatric transplants the average size discrepancy between donor and recipient was 150%, and in a cohort of patients who had a failing Fontan circulation as an indication for transplantation, the oversizing was 250%. The adverse consequences of oversizing are delayed sternal closure, collapse of the left lower lobe and systemic hypertension. However, all these factors can resolve with time and appropriate treatment.

ABO compatibility

ABO compatibility is required to avoid hyperacute or accelerated acute rejection. Rhesus incompatibility is acceptable. The only ABO exception would be the A2 subgroup as donors with this subgroup may be less prone to producing hyperacute rejection, because A2 antigen is not readily displayed on the endothelial surface of the heart. However, in the paediatric group successful heart transplantation has been undertaken in the presence of ABO incompatibility.18 This is possible as the immune system in infants is immature and their anti-A and anti-B titres remain low until 12–14 months of age. We have successfully undertaken 10 transplants in children with ABO incompatibility.30 The oldest was 18 months old when heart transplantation was performed.

Immunological matching

The rationale for undertaking immunological testing is to identify potential recipients with circulating anti-HLA antibodies to avoid mismatch between donor and recipient that could lead to hyperacute or accelerated acute rejection (see Chapter 4).

Common causes of sensitisation are pregnancy, prior blood transfusion or insertion of a ventricular assist device. Rarely, a patient may be sensitised for unknown reasons. The test is considered positive if a 10% threshold is reached on testing the donor serum with the control group. When the recipient has detectable panel-reactive antibodies (PRAs), a prospective crossmatch is undertaken, which has implications regarding the timing of transplantation and in our experience does disadvantage the recipient. The long-term results of recipients having more than 25% PRAs show that they are more prone to rejection.31

Donor heart procurement

It is important to optimise the haemodynamic, metabolic and respiratory condition of the donor to maximise the yield of donor organs. This may entail using a multidisciplinary team to manage and optimise the donor before retrieval. Some poorly functioning hearts could be resuscitated by careful manipulation of inotropes and loading conditions of the heart. Using this strategy up to 30% of such hearts can be successfully ‘resuscitated’ and used for transplantation.32

Once the cardioplegia has been given the cardiectomy can proceed further. The superior vena cava is incised above the previous ligature. The aorta is now divided below the innominate artery; this exposes the pulmonary artery, which is divided on the left side where the left pulmonary artery is attached to the pericardial reflection and the right pulmonary artery is divided behind the aorta. The left atrium is now incised at the level of the pericardial reflection. Due consideration to leave sufficient left atrial tissue along each pulmonary vein is essential when lungs are procured for transplantation.

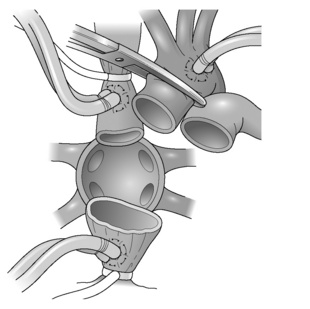

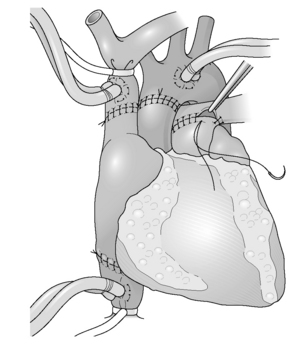

Heart transplantation (Figs 11.1 and 11.2)

The classical technique of orthotopic heart transplantation as described by Lower et al. has remained the standard operation for 30 years.33

The most significant modification to heart transplant procedure has been the use of a bicaval technique. This results in less tricuspid regurgitation and better haemodynamic performance of the implanted heart.34

The most significant modification to heart transplant procedure has been the use of a bicaval technique. This results in less tricuspid regurgitation and better haemodynamic performance of the implanted heart.34

The operation is undertaken with a midline sternotomy. Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is established with right atrial venous cannulation to allow decompression of the heart; this allows for easier cannulation of superior and inferior venae cavae. The patient is then cooled to 32 °C. The cavae are now snared and the aorta is clamped. To facilitate bicaval anastomosis it is recommended that at this stage the interatrial groove is dissected to develop a cuff of left atrium. The cardiectomy proceeds with a right atrial incision, which runs parallel to the atrioventricular groove; care is taken at the inferior caval end of this incision to preserve as much tissue as possible to facilitate inferior caval anastomosis. An incision is then made in the roof of the left atrium to further decompress the heart before dividing the aorta just above the aortic valve. Retracting the heart downwards now exposes the pulmonary artery, which is again divided above the pulmonary valve. The superior vena cava is now divided just at its right atrial junction. The heart is now only attached to the pulmonary veins and via a small bridge of tissue to the inferior vena cava. The inferior caval attachment is divided, again being mindful of the inferior vena cava (IVC) cuff; the incision in the left atrium is now extended to encircle the pulmonary veins, leaving behind two pulmonary veins on each side attached with a bridge of tissue.

Special situations

Heart transplantation for congenital heart disease

This group of patients presents special technical challenges due to unusual anatomy, previous operations and raised pulmonary vascular resistance. Heart transplantation can be undertaken to overcome most structural abnormalities.35