CHAPTER 24 Total Ankle Replacement

OVERVIEW

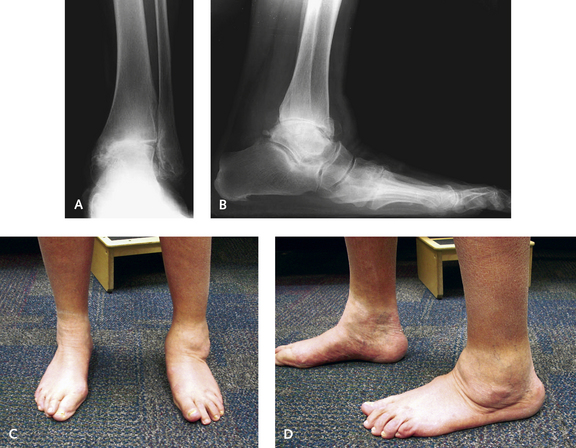

An important consideration in surgical planning is the preoperative range of motion of the ankle. One of the most critical factors affecting the postoperative range of motion is a preexisting contracture, which is often the case with posttraumatic arthritis. The soft tissue envelope around the posttraumatic and arthritic ankle joint usually is quite scarred, at times significantly so. Contractures developing over long-term periods of immobilization further adversely affect the ankle joint mobility. In such cases, it is more difficult to obtain a satisfactory range of motion even intraoperatively, despite aggressive soft tissue release. A patient with severe ankylosis may never achieve an acceptable range of motion regardless of how the procedure is performed. For such patients, arthrodesis may not be perceived as disabling (in comparison with those in whom the clinical presentation includes a reasonable range of motion but some degree of preoperative pain) (Figure 24-1). It is important to identify the true range of motion of the ankle joint, which can be clinically deceptive because “motion” may actually represent mobility of the transverse tarsal joints (Figure 24-2). I routinely obtain dynamic lateral plantar flexion and dorsiflexion radiographic views of the ankle during the preoperative evaluation to identify the exact location of sagittal plane motion.

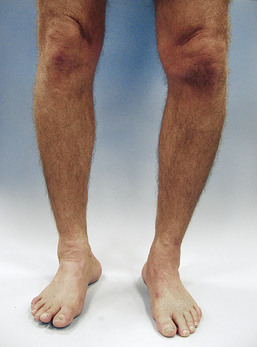

The alignment of the foot and ankle is an important determinant of suitability for replacement surgery. There are limits to correction of a varus or valgus deformity, which I generally set at approximately 20 degrees for varus and 10 degrees for valgus. As discussed later in the section on managing associated deformity, if the deltoid ligament is torn, the likelihood of obtaining a well-aligned ankle is significantly decreased (Figures 24-3 and 24-4). Tibia varus or valgus deformity should be addressed before ankle replacement, particularly if the knee is affected, in which case the knee must be first corrected (Figure 24-5).

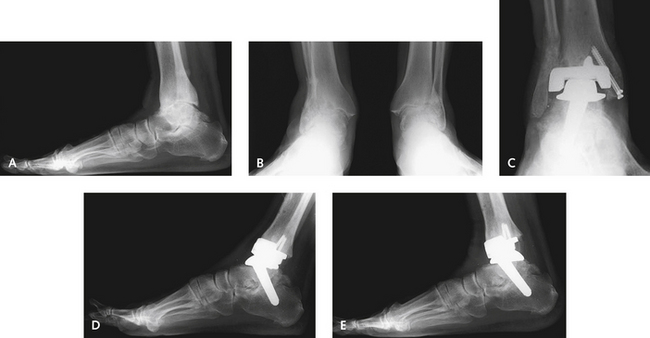

Bone quality is an important consideration, and if severe osteopenia is present, the likelihood of subsidence of the prosthesis is increased. The risk increases if avascular necrosis is present. The talar component is more likely to subside than the tibial component, particularly if osteopenia or avascular necrosis is present. To circumvent this problem of poor-quality bone, selection of a prosthesis with a long stem is a good option. This is combined with a subtalar arthrodesis, providing a very stable platform for the prosthesis (Figure 24-6).

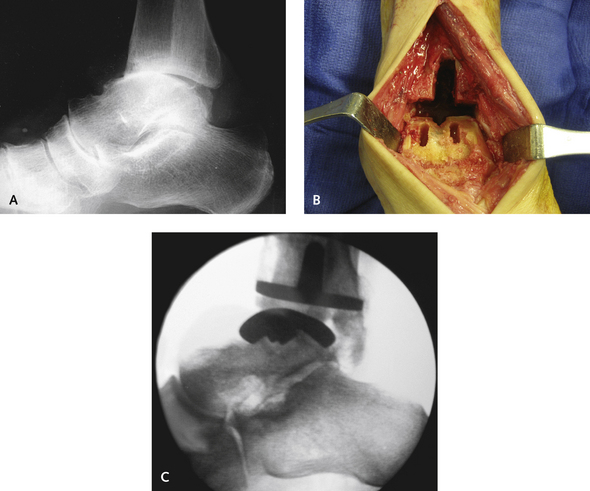

Preoperative instability of the ankle is very important to ascertain, and treatment should be planned accordingly. Certain deformities seem trivial but should be approached with caution. An unstable ankle typically is thought to be associated with a lack of lateral ligamentous support. Such instability is problematic only if not identified intraoperatively, because a ligament reconstruction is always possible to restore stability. If the deltoid is torn, however, restoration of medial stability will be unpredictable. Another pattern of instability that is difficult to treat is anterior subluxation of the talus under the tibia (Figure 24-7). This displacement may resolve with correct positioning of the prosthesis and correct tensioning with a larger polyethylene (“poly”) insert, but the outcome is not predictable, and anterior subluxation should be approached surgically with caution.

Combined surgeries are commonly performed for associated deformity and arthritis. I recommend simultaneous hindfoot arthrodesis. The talonavicular arthrodesis is straightforward, because the incision is simply extended slightly distally. A lateral incision can be used for an isolated subtalar arthrodesis or a subtalar and calcaneocuboid arthrodesis (Figure 24-8). The fixation of these joints can be difficult, but correctly positioned screws or plates are used without interfering with the prosthesis. This consideration is of particular importance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Repeated bouts of immobilization lead to increased osteopenia with the potential for implant subsidence or fracture. Simultaneous joint replacement–arthrodesis has its advantages (Figure 24-9). If hardware is present in the tibia or talus, it obviously has to be removed if it interferes with correct positioning of either the tibial or the talar component. Of note, however, removal of hardware may create a stress riser, particularly in the medial malleolus (see Figure 24-9). Screws that strip on attempted removal constitute more of a problem: additional bone has to be removed to core out the screw with a screw removal device. Screws in the medial malleolus may interfere with insertion of the tibial component, and they should not be removed intraoperatively, regardless of the type of prosthesis, unless the malleolus is reinforced with temporary Kirschner wires (K-wires).

TECHNIQUES, TIPS, AND PITFALLS

Replacement With All Implants