A role for use of bulk fresh allografts in ankle surgery has been well established. Although the enthusiasm for large fresh allograft osteoarticular ankle replacement has diminished over the past several years, this technique remains an effective approach to reconstruction in the appropriate patient. Furthermore, the options for treating sizable cystic lesions in either the distal tibia or the talus are very limited without the use of fresh osteoarticular grafts. In general, the smaller the size of the graft used, the less likely it is that failure will occur, whether from necrosis, collapse, graft fracture, or development of arthritis. The evidence to date suggests some critical volume of graft material or immunogenic load that the ankle can tolerate before rejection or failure occurs. In my own clinical experience in numerous patients, large bulk osteoarticular replacement grafts of the ankle have lasted more than 8 years with no complications. Such cases, however, constitute the exception rather than the rule, because a majority of these grafts have failed over time. The decision to use a fresh graft in reconstruction for a massive osteochondral lesion is far easier, because few realistic alternatives are available, and the results with this procedure have been excellent over the years.

The osteoarticular replacement procedure is indicated for patients with end-stage arthritis and for whom either an arthrodesis or total ankle replacement is not ideal. Considerations in selection of suitable candidates for this procedure include the patient,s age, activity level, weight, and desire for continued mobility of the ankle. The most significant aspect of surgical planning involves assessing the potential for failure. Certainly, a primary ankle arthrodesis has a recognized success rate, from a technical standpoint, that should be greater than 95%. If an ankle arthrodesis becomes necessary after failure of an osteoarticular allograft replacement, clearly this success rate is lower, with failure attributed to graft collapse, sclerosis, or avascular necrosis. The other options after failure are to repeat the graft procedure or to perform a total ankle replacement. These procedures are much easier, provided that the appropriate criteria for an ankle replacement are met. Accordingly, committing to an osteoarticular replacement procedureis a difficult clinical decision, because the failure rate over the past several years has been approximately 60%. I therefore limit use of the graft procedure to patients who have met most of the criteria for an ankle replacement but who prefer a more “physiologic” approach. Undoubtedly the worst candidate for grafting procedures is a patient who is young and active and has limited motion of the ankle to begin with, the result of posttraumatic arthritis.

Tissue typing is not necessary for this procedure. The most important aspect of planning this surgical procedure is correct sizing of the graft, because it must fit perfectly. If the graft is a few millimeters too small, the ankle will still function well, because the “fit” occurs between the articular surfaces of the tibia and the talus. If the graft is too large, however, it will not fit at all, and although the tibia can be cut laterally, the talus will abut against the malleoli.

The incision is identical to that for total ankle replacement: an anterior central midline incision over the ankle. Once the joint has been exposed and denuded of all juxtarticular osteophytes, the anterior aspect of the distal tibia is resected so that the plafond can be completely visualized. This clear view helps with planning the tibial cut correctly. Although the cuts on the tibia can be made freehand, use of a cutting block for the tibial cut is easier and permits better precision. The sizing of the cutting block is important, and 7 mm of distal tibia is removed. Judging the position of the cutting block relative to the lateral aspect of the ankle, which is not cut, is unimportant. The position of the block must be verified carefully by fluoroscopic examination, and minor adjustments must be made until the block is positioned to remove approximately 7 mm of the distal tibial surface.

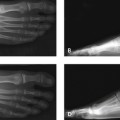

In cutting the tibia, it is important to protect the articular surface of the fibula and the medial malleolus. Sometimes the fibular articular surface is abnormal because of articular wear or deformity, such as shortening or external rotation. I do not normally disturb the fibula, although clearly for some cases, an osteotomy of the fibula may be required to restore length and correct rotational deformity simultaneously. The bone is then carefully pried off the tibia, and the remaining lateral tibia is then removed in segments with a small osteotome until the entire joint is visible (Figure 22-1). The talar cut is made freehand, with removal of approximately 5 mm of bone in the center of the dome of the talus (Figure 22-2). The tibial graft is then sized, and the cutting block is applied to the tibia under fluoroscopic guidance so that an identically sized matching graft can be harvested (Figure 22-3). At times, it is easier to remove a larger-size graft from the distal tibia and then shave this to a perfect cut once the size match is confirmed on the patient. The tibial graft rarely fits perfectly because of the anatomic constraints of the anterior and posterior ankle and the position of the fibula posterolaterally. The graft is then slotted into place, and minor adjustments to the diameter and depth of the graft can be made with a saw to ensure a perfect fit.