CHAPTER 39 The Rheumatoid Foot and Ankle

FOREFOOT RECONSTRUCTION

The concept of joint preservation of the MP joint is an important one in patients with inflammatory joint disease. The synovitis surprisingly decreases with mechanical off-loading of the MP joint as a result of the shortening osteotomy. Although the lesser metataral osteotomy is a reasonable procedure to be performed in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis, it is not easily accomplished because of the paucity of good bone around the metatarsal head, the erosive changes typically associated with joint subluxation and dislocation, and the difficulty of performing this operation while maintaining a salvageable joint. Nonetheless, in patients who have involvement of one or two joints without severe erosion, shortening osteotomy is an option. This procedure is indicated especially when one or two of the lesser MP joints are involved, and resection of all of the metatarsal heads is inadvisable for some reason (Figure 39-1).

Many intermediate stages of deformity of the rheumatoid forefoot exist in which arthrodesis of the MP joint may not be considered necessary. A good example is the presence of hallux valgus in an otherwise healthy joint. In this instance, a standard operation for correction of hallux valgus (e.g., bunionectomy and metatarsal osteotomy) may not be as successful as, for example, a tarsometatarsal arthrodesis (the modified Lapidus procedure) (Figure 39-2). If hallux valgus is not present initially and metatarsal head resections are performed, then the hallux deformity will always increase as a result of shortening of the lesser toes in the absence of a lateral buttress to the hallux. Preservation of the hallux MP joint is even more relevant if joint preservation osteotomy procedures of the lesser metatarsal heads are performed.

INCISIONS AND DISSECTION

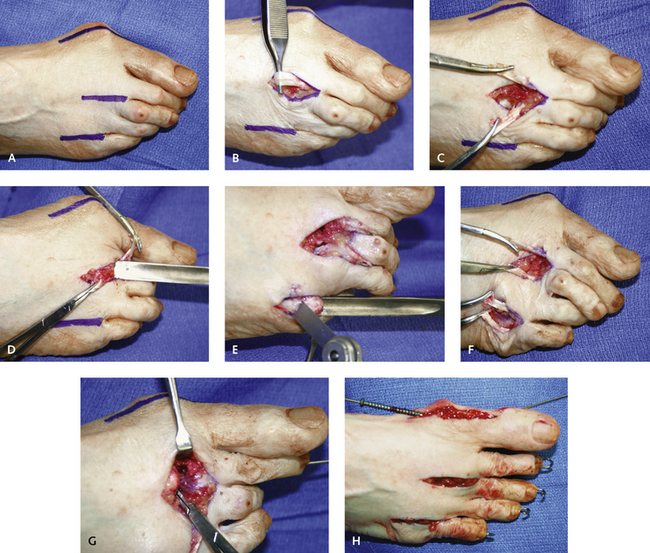

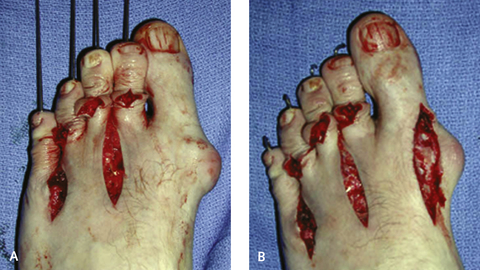

The choice of incisions used for the metatarsal head resections or the metatarsal head osteotomies is determined by the magnitude of deformity. In general, I prefer two dorsal longitudinal incisions made in the second and fourth web spaces (Figure 39-3). The improved access with these incisions, however, must be balanced against the possibility of wound dehiscence and associated problems with skin healing in this region. The option of a dorsal transverse incision is available, but not if dislocation of the MP joints is present with shortening and contracture of the soft tissues. Although the transverse incision is easier to perform and can be done with far less retraction than with two longitudinal incisions, the surgeon must be certain that sufficient bone has been resected to facilitate soft tissue closure. The other option is a plantar surface–based elliptical incision. Although I have used this incision on occasion, it is associated with problems with management of the contracted dorsal soft tissues, including the extensor tendons and capsule. I see no advantage to use of a plantar surface–based incision other than the proximity of the metatarsal heads. The hypertrophied soft tissue, callus, or bursae are always resorbed once the metatarsal heads have been resected, and the excision of an ellipse of tissue on the plantar surface does not seem warranted (Figures 39-4 and 39-5).

The correction of the claw toe deformities often has been described as unnecessary. Of note, however, if the toes are left deformed at the proximal IP joint, MP joint deformity tends to recur later as well. These contractures should be addressed with either manual manipulation of the joint or resection arthroplasty. Although a formal arthroplasty is my preferred procedure (Figure 39-6), manual manipulation of the joint occasionally will be successful in other than rigid contractures.