CHAPTER 3 The Modified Lapidus Procedure

OVERVIEW

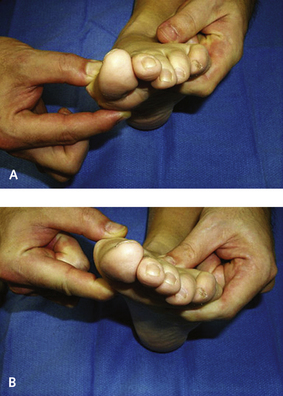

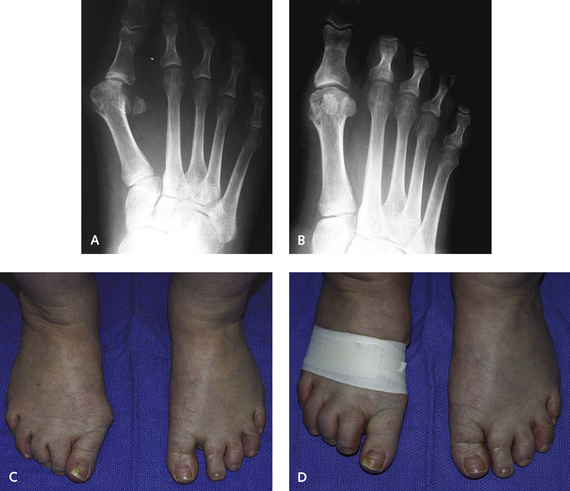

Examination for sagittal plane instability or hypermobility is best performed by stabilizing the lateral aspect of the foot and then manipulating the medial column in a dorsal or plantar direction (Figure 3-1). There is obviously a “feel” to this examination, and although objective interobserver reliability may not be achievable among surgeons who examine the foot for instability, each surgeon should establish personal criteria for what is normal and what is abnormal. An important component of this test for increased first ray mobility is to establish that it is only the first metatarsal and not the entire medial column that is mobile. By pushing the lateral column into maximum dorsiflexion and then testing the first ray, a more accurate result will be obtained. Radiographic parameters of instability are helpful but unreliable in planning this operation; however, instability in the transverse plane is easy to document (Figure 3-2).

INCISION AND DISSECTION

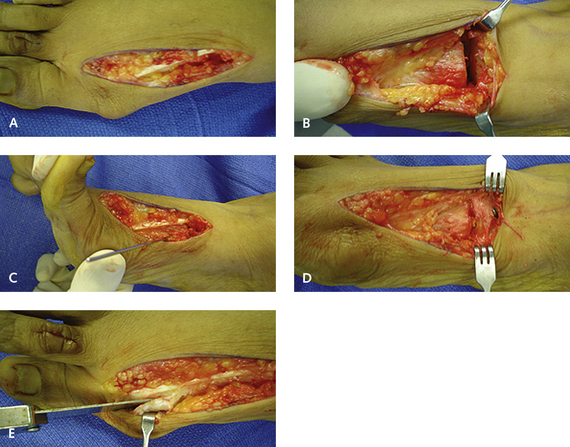

I used to perform the procedure using three incisions, one for the distal soft tissue release, one for the exostectomy and the capsulorrhaphy, and one for the arthrodesis. I have found that one long dorsal incision is cosmetically preferable, and indeed, the exostectomy can be performed through the same incision or may not be needed at all (Figure 3-3). After the distal soft tissue and adductor release, the incision is extended proximally, lateral to the extensor hallucis longus tendon, without injury to the deep peroneal nerve. In my experience, this single midline incision is more cosmetically acceptable and facilitates exposure of the TMT joint proximally. The exostectomy is not performed at this time, because subtle rotation of the metatarsal may occur after arthrodesis, changing the axis of the exostectomy, and if the arthrodesis is performed correctly, it is often not necessary to do an exostectomy. The extensor hallucis longus tendon is retracted medially, and with subperiosteal dissection, the dorsal surface of the articulation is identified and opened. The key to the joint debridement is restraint, because only the articular cartilage and minimal subchondral bone should be removed.

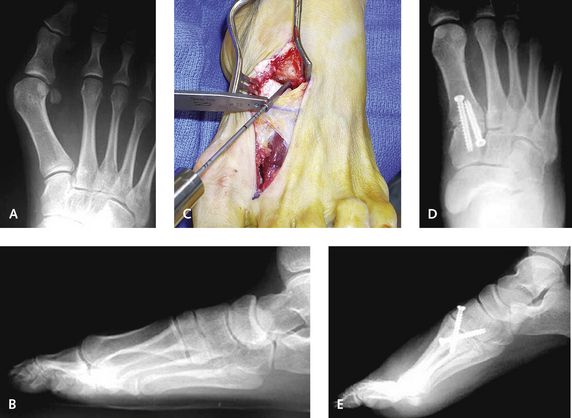

Although the first metatarsal is moved laterally during the procedure, such movement is not performed through removal of any wedges of bone, which shortens the metatarsal. Instead, translation and rotation of the metatarsal base are preferable. The ease of this manipulation will depend on the configuration of the articulation, which typically is saddle-shaped and may not be amenable to this translational movement. A smooth laminar spreader is inserted into the TMT articulation, and the joint is distracted to provide visualization of the plantar surface of the first metatarsal. The joint is much deeper than might be expected, and for prevention of a dorsal malunion, the entire joint must be denuded. I prefer to use a chisel instead of a saw blade to denude the articular cartilage, and then I perforate the joint multiple times using a small drill bit down to healthy bleeding subchondral bone on both the metatarsal and cuneiform surfaces (Figure 3-4). The perforation of the joint surfaces probably is the most important component of the procedure, and with this minor change to technique, I have rarely encountered a nonunion over the recent past.