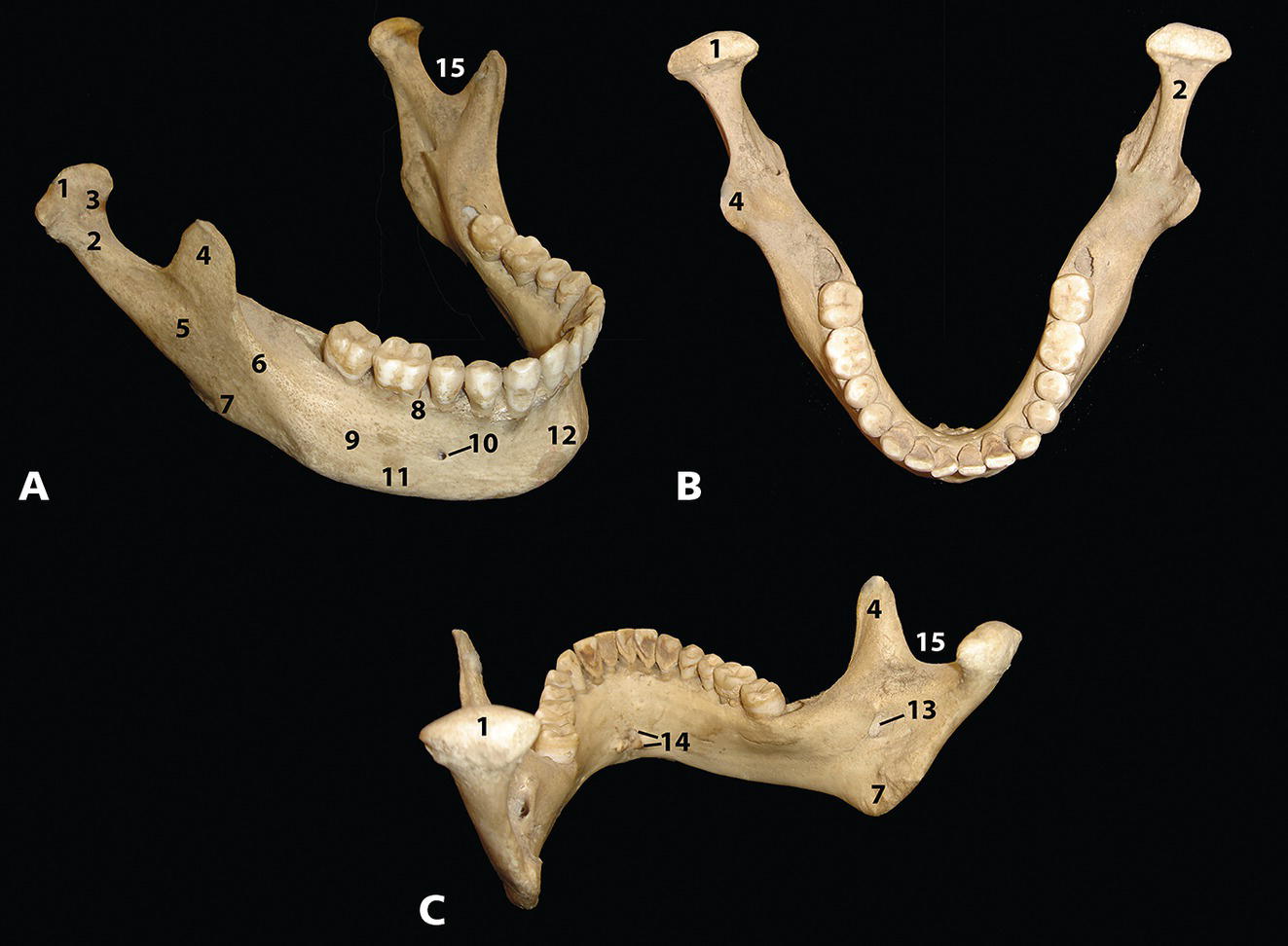

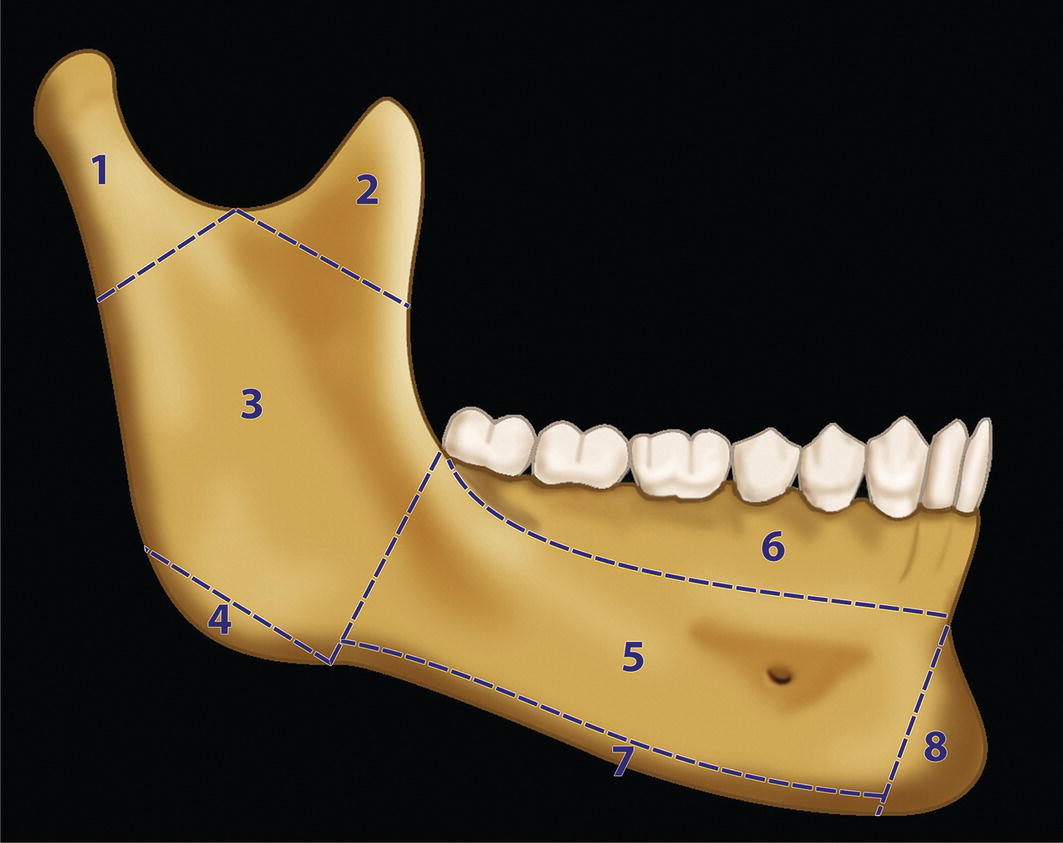

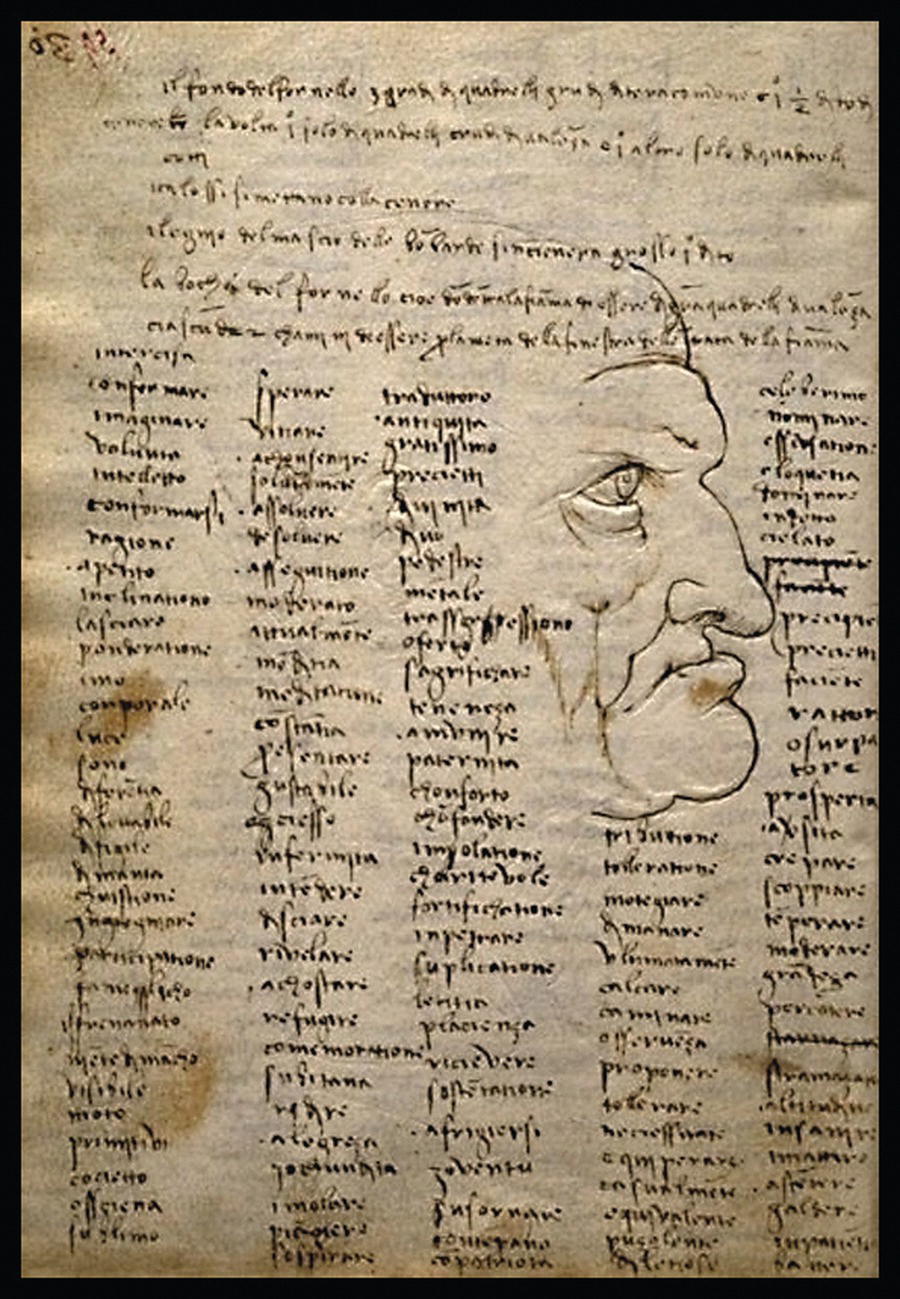

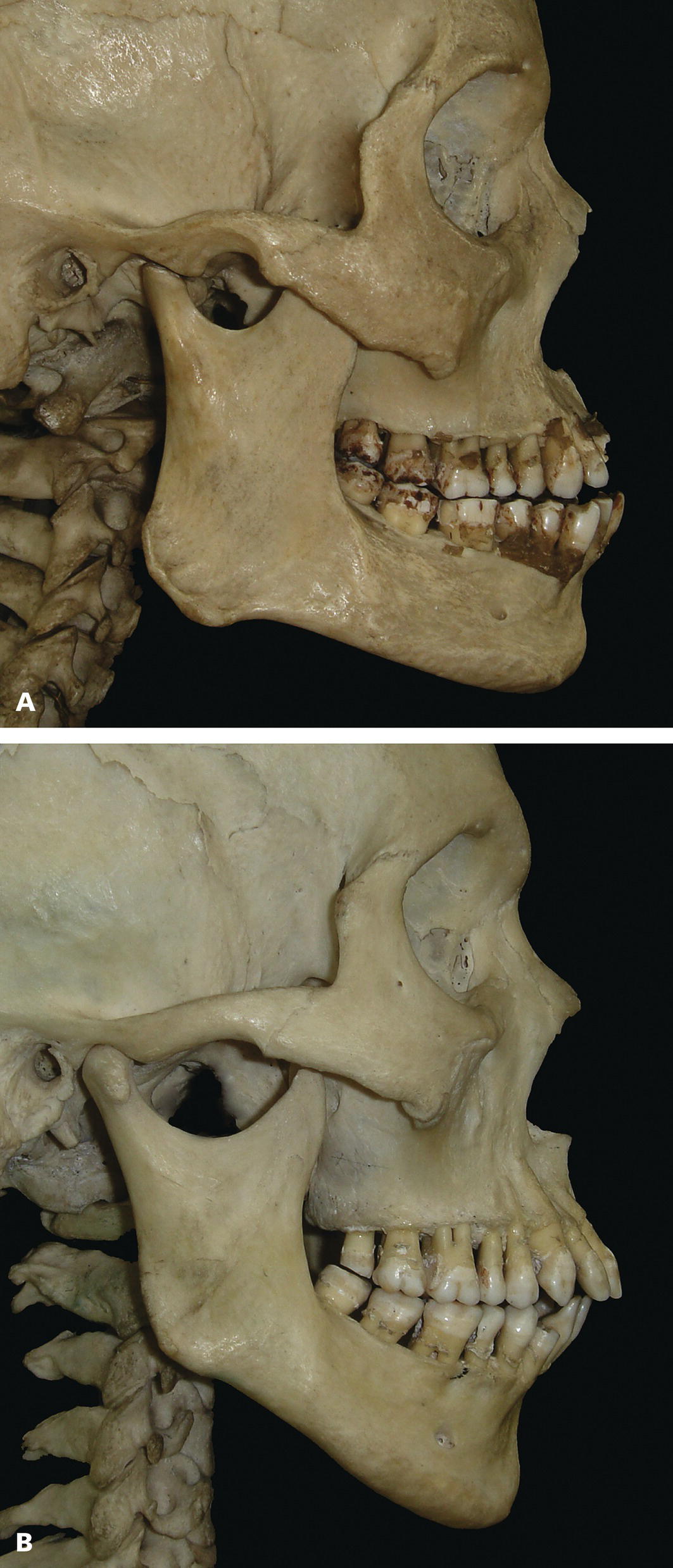

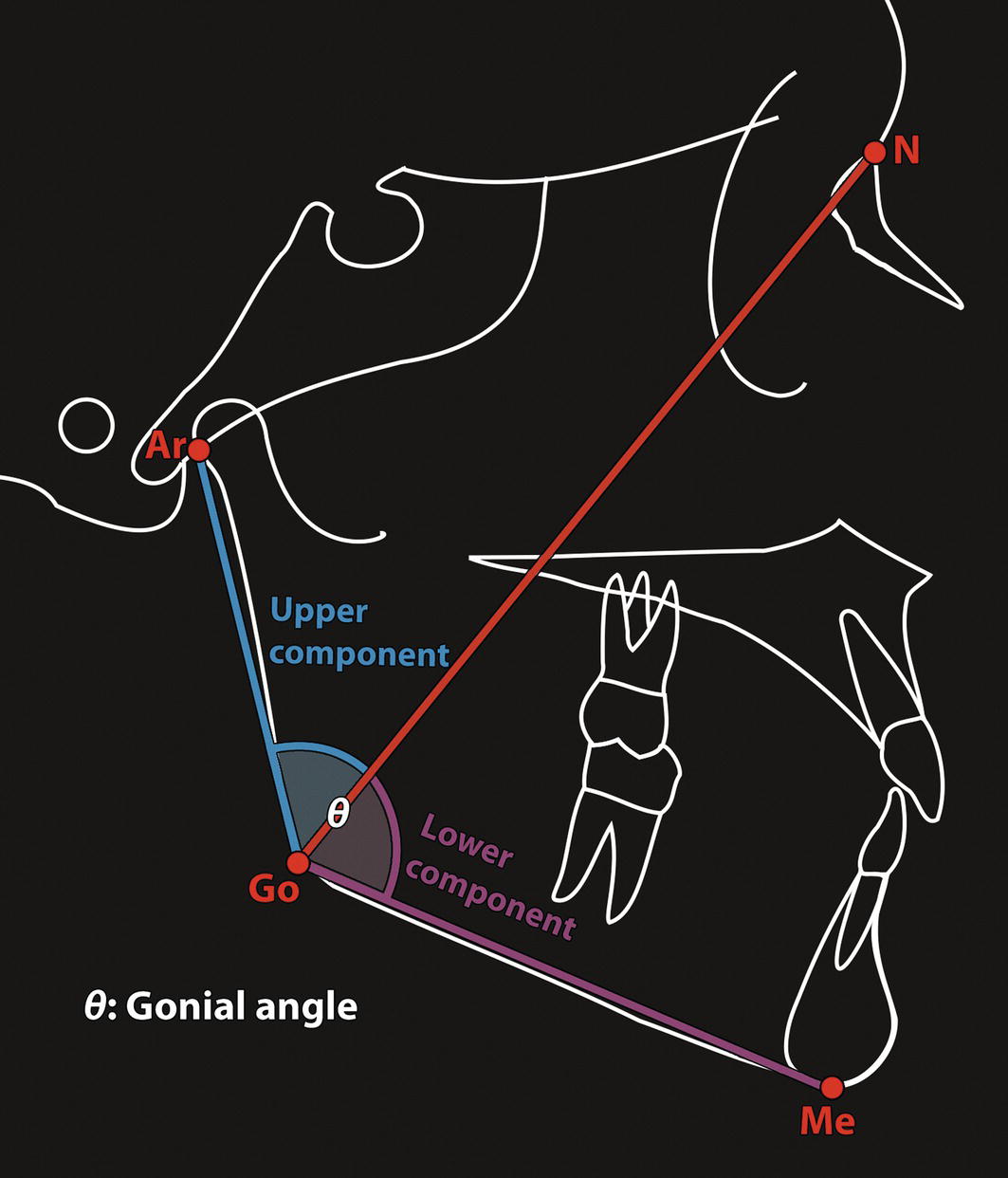

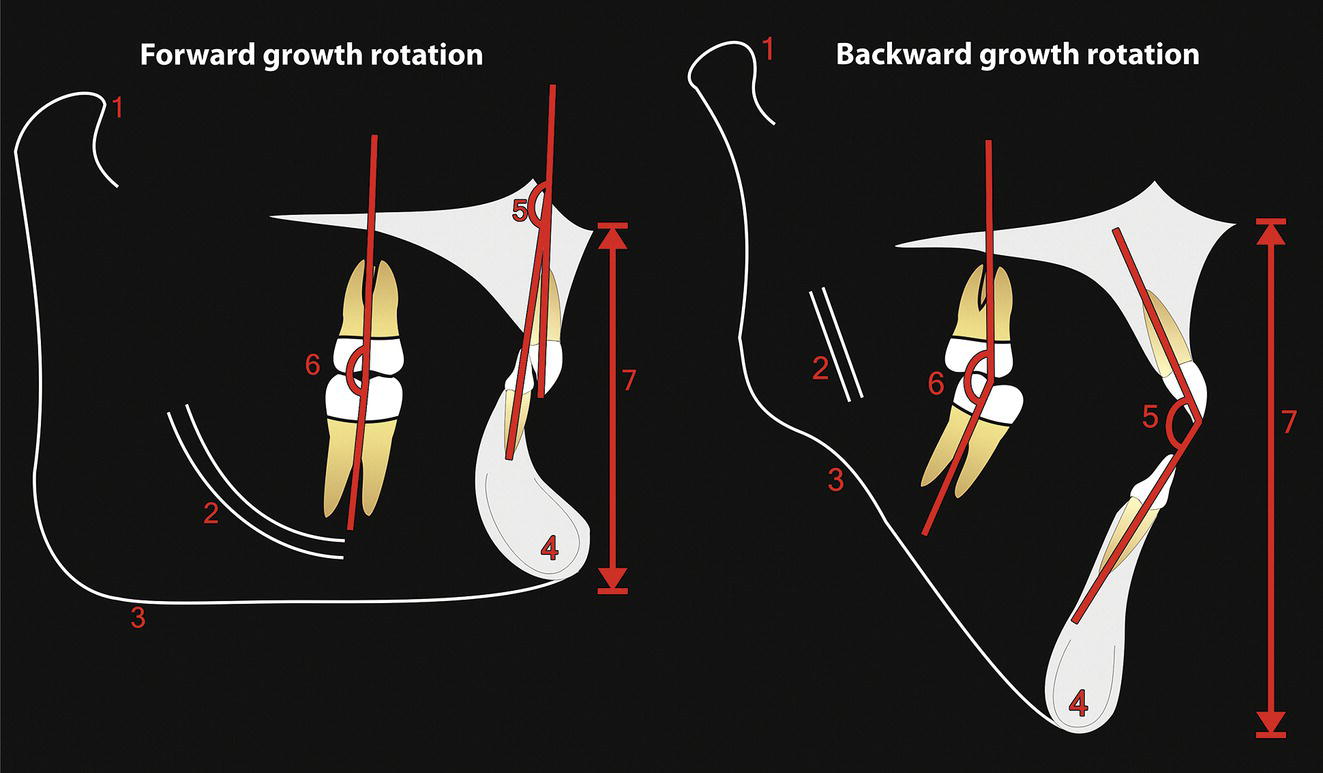

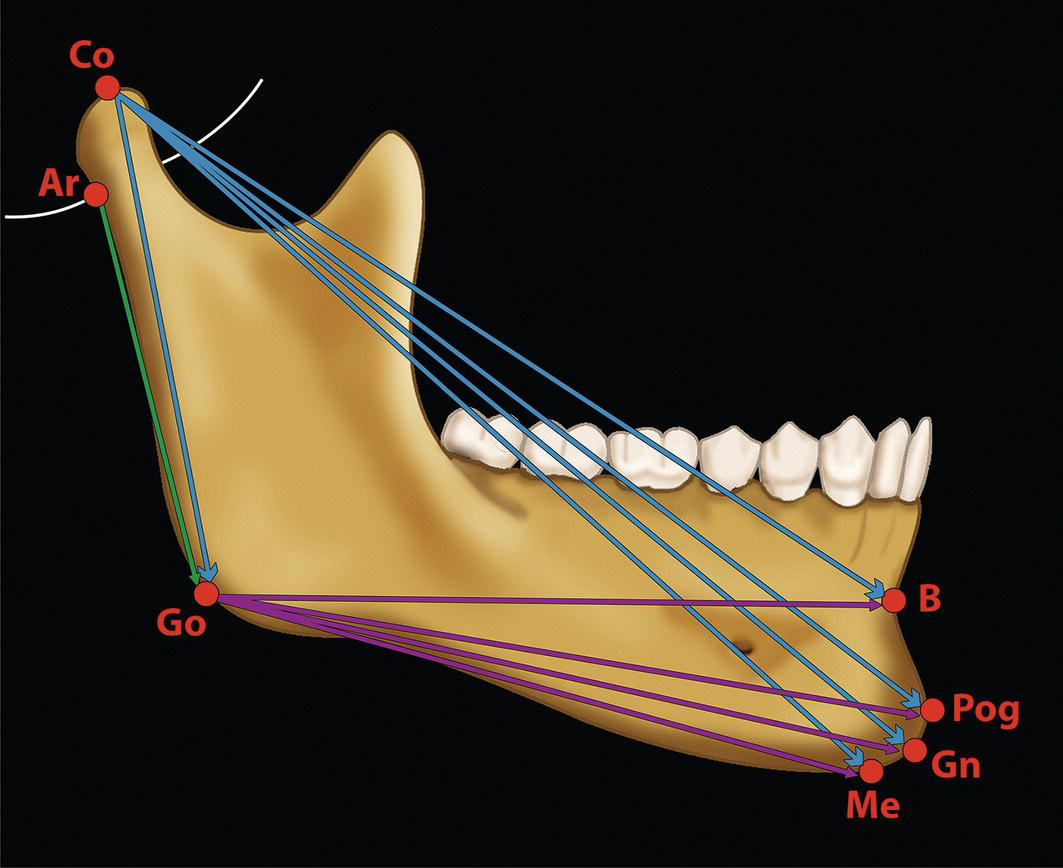

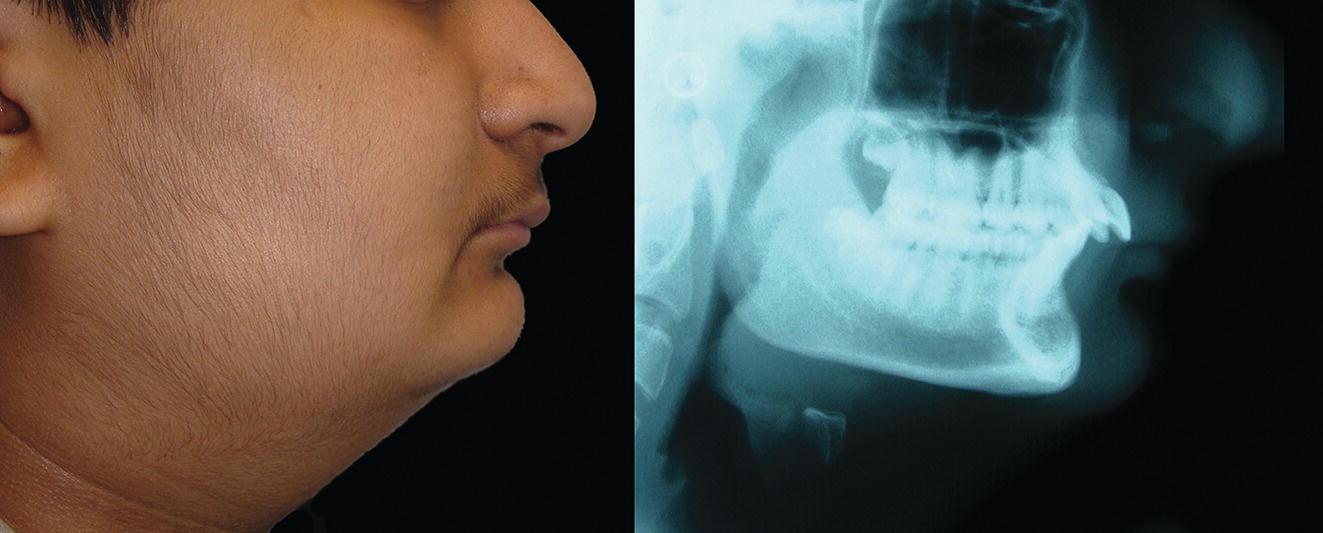

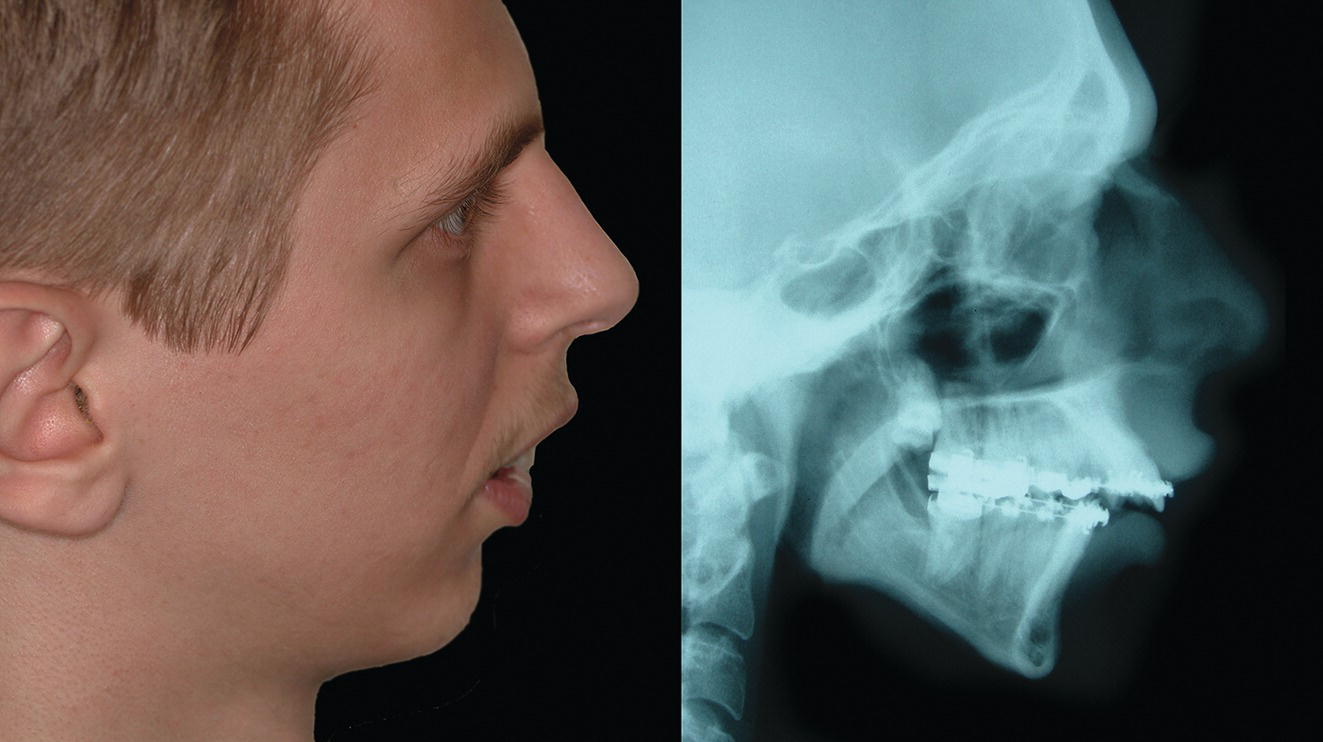

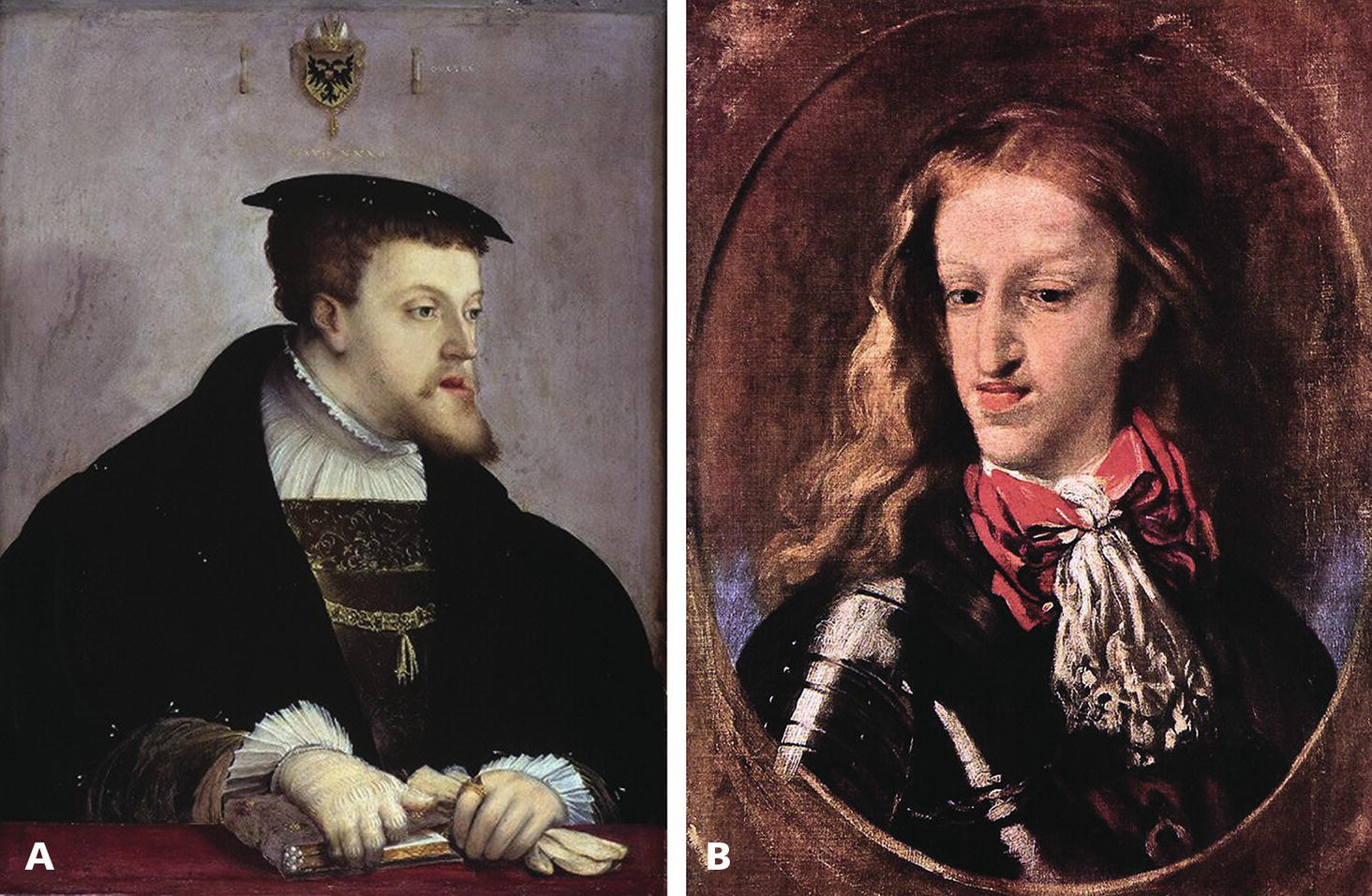

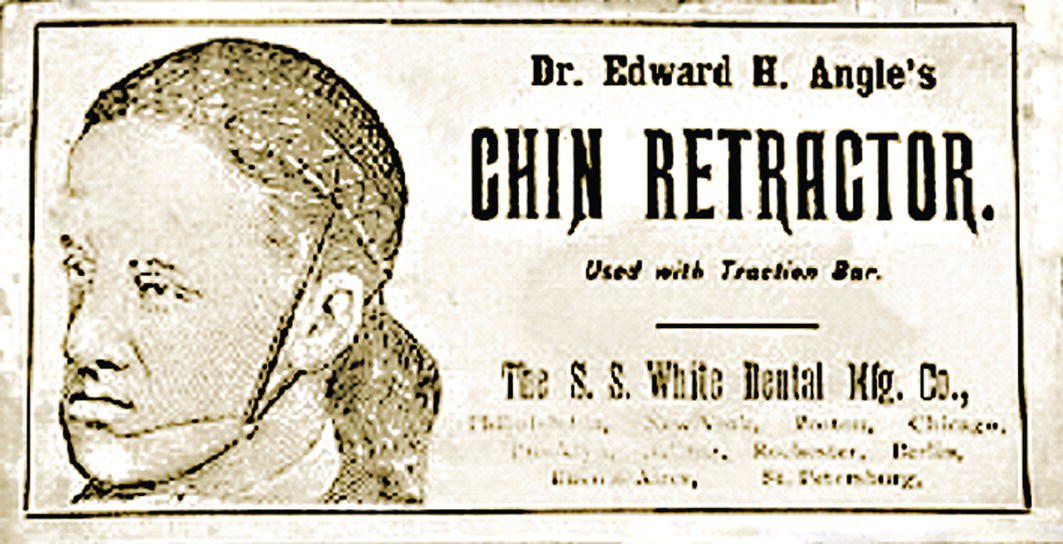

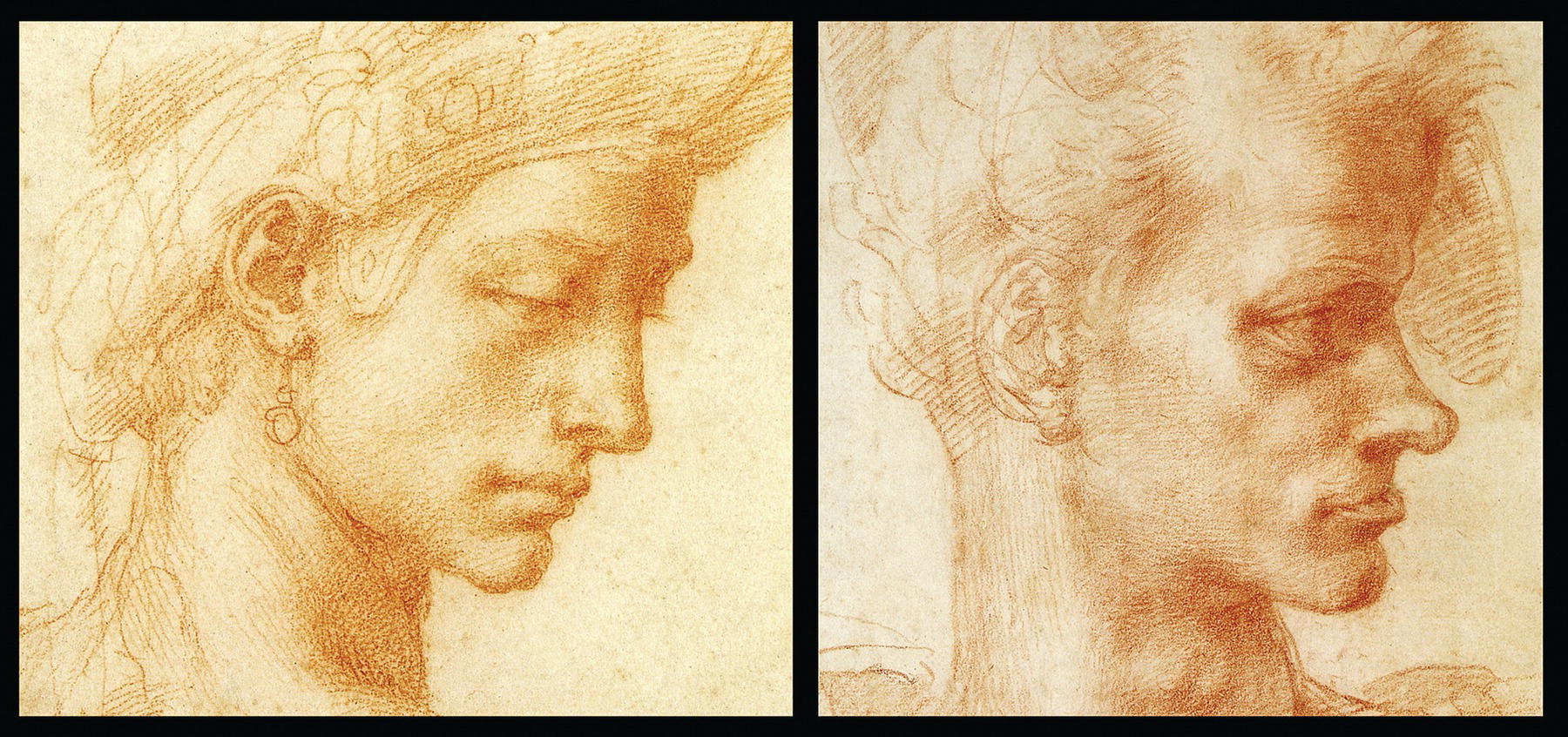

See ‘terminology’ section in Chapter 16. The mandible, the bone of the lower jaw, is one of the most important bones in the craniofacial complex; its anatomy and structural relationships are thus highly significant (Figure 19.1). For descriptive purposes, the mandible may be said to be comprised of a number of subunits: the two main parts are the ramus, which is for articulation and the insertion of jaw‐moving muscles, and the body (corpus), which carries the dentition (Figure 19.2). The body is horseshoe‐shaped when viewed from above, and the two vertical rami project upwards one from each posterior end of the body. The posterior border of the ramus projects upwards as the condylar process, which consists of a neck, expanding into a condylar head or condyle. The body of the mandible projects up around the teeth as alveolar bone, which forms the walls of the tooth sockets. After loss of a tooth the living alveolar bone atrophies. Extensive tooth loss may thereby lead to a reduction in lower anterior face height due to loss of the dentoalveolar process (Figure 19.3). The inferior border of the mandible provides the demarcation between the lower face and neck. The anterior extremity of the mandibular body is the highly variable prominence of the mandibular or mental symphysis (bony chin). Typical morphology: The morphology of the mandible (excluding the bony chin) is relatively consistent, depending on the basic type of dentofacial deformity with which a patient may present, e.g. ‘Class II’, ‘Class III’, ‘short face’ or ‘tall face’. Conversely, the morphology of the bony chin is highly variable and will be described in detail in Chapter 20. Gonial angle (Ar‐Go‐Me): This is a measure of the angle formed between the slope of the posterior border of the mandibular ramus and the mandibular plane. It helps to describe the morphology of the mandible, in particular the relationship between the ramus and the body (Figure 19.4). It is highly correlated with the mandibular plane angle. An increased gonial angle is associated with posterior mandibular growth rotation, and a reduced gonial angle is associated with anterior mandibular growth rotation. In order to determine the relative contribution of the ramus and body of the mandible to mandibular morphology, the gonial angle may be divided into two parts, an upper and lower component, by drawing a facial depth line (nasion‐gonion). The upper component of the gonial angle (50° ± 2°) identifies the inclination of the ramus and the lower component identifies the inclination of the body of the mandible (Figure 19.5).3 Figure 19.1 (A) Oblique right lateral view. (B) Superior view. (C) Oblique left posterior view. Figure 19.2 Mandibular subunits: Figure 19.3 Extensive tooth loss results in resorption of the alveolar process and thereby a reduction in the lower anterior face height; the mandible will rotate anteriorly bringing the chin characteristically closer to the nose. (Head of an Old Man, c. 1487–90, Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Trivulzianus, Sforza Castle, Milan.) Figure 19.4 (A) Reduced, acute gonial angle. (B) Increased, obtuse gonial angle. Figure 19.5 The gonial angle may be divided into an upper and lower component in order to determine the relative contribution of the ramus and body inclination to mandibular morphology. Mandibular growth rotations: Growth rotations of the mandible occur when there is a discrepancy in the amount of anterior and posterior lower facial heights. It is important to bear in mind that the amount of rotation is masked to some extent by periosteal remodelling and dentoalveolar adaptation. Forward (anterior) rotation of the mandible, in the direction of mouth closing, is due to increased posterior vertical facial growth relative to anterior vertical facial growth (Figure 19.6A). Backward (posterior) rotation of the mandible, in the direction of mouth opening, is due to reduced posterior vertical facial growth relative to anterior vertical facial growth (Figure 19.6B). Björk4 described seven structural signs found on a lateral cephalometric radiograph, which may provide an indication to the pattern of mandibular growth (Table 19.1 and Figure 19.7). Inferior border of the mandibular body: The lower border of the mandible should be well‐defined, providing distinct separation of the lower face from the neck. This region will be relatively unattractive in the absence of such demarcation between the lower face and neck, which may be due to skeletal and/or soft tissue factors (Figure 19.8): Figure 19.6 (A) Forward (anterior, anticlockwise) rotation of the mandible, in the direction of mouth closing, is due to increased posterior vertical facial growth relative to anterior vertical facial growth. (B) Backward (posterior, clockwise) rotation of the mandible, in the direction of mouth opening, is due to reduced posterior vertical facial growth relative to anterior vertical facial growth. Table 19.1 Björk’s seven structural signs indicating the pattern of mandibular growth rotation For the numbers refer to Figure 19.7. A thorough clinical evaluation of this region is required, involving clinical inspection and palpation. The lateral cephalometric radiograph, orthopantomograph (OPT) and where necessary three‐dimensional reconstruction of the mandible permits more accurate analysis of the inferior mandibular border. When skeletal and soft tissue factors coexist, surgical correction to redefine the natural demarcation in this region may involve augmentation of the lower mandibular border and gonial angles in conjunction with rhytidectomy. Figure 19.7 Björk’s seven structural signs, which may be used to indicate the pattern of mandibular growth (for an explanation of the numbers, refer to Table 19.1). Figure 19.8 Indistinct inferior border of the mandible. Mandibular micrognathia (a small mandible) may have reasonable proportionality between the ramus and body. Although hypoplasia of the mandible may affect the ramus, body or both, syndromic mandibular deficiency is often due to a short mandibular ramus. The surgical technique of distraction osteogenesis may be used to differentially lengthen the ramus and/or the body of the mandible. The craniofacial dimensions of patients with craniofacial syndromes in particular may not fit into normal ranges of variability. Therefore, the use of proportional analysis rather than comparison with population ‘norms’ is a useful method of evaluating the specific area (ramus or body), direction and extent of lengthening that may be required. The characteristic feature of sagittal mandibular deficiency, and the most common complaint from the ‘Class II’ patient, is the retruded position of the chin relative to the rest of the face in profile view. It is important to distinguish true skeletal mandibular deficiency from relative mandibular deficiency. True sagittal mandibular deficiency may be due to: Relative mandibular deficiency may be due to: Table 19.2 Normal mandibular dimensions (white Caucasian adults) Refer to Figure 19.9. Figure 19.9 Mandibular dimensions (for normative values see Table 19.2). The aetiology of mandibular deficiency may result from a combination of relative and true mandibular deficiency. The diagnostic features of sagittal mandibular deficiency depend to a great extent on the lower anterior facial height (LAFH). In patients with sagittal mandibular deficiency and a normal or reduced LAFH, the diagnostic features are (Figure 19.10): Figure 19.10 Sagittal mandibular deficiency with a reduced lower anterior facial height. Figure 19.11 Sagittal mandibular deficiency with an increased lower anterior facial height. In patients with sagittal mandibular deficiency and an increased LAFH, the diagnostic features are (Figure 19.11): The aetiology of Class III jaw deformity, in particular mandibular excess, has a very strong genetic basis.7 The familial tendency of Class III deformity may be frequently observed in members of the same family. A famous example is of the Hapsburg dynasty, one of the German royal families. Over 23 generations, portrait painters have captured images of the Hapsburgs, and they all exhibit the same mandibular prognathism and protrusive lower lip, often termed the ‘Hapsburg jaw’ (Figure 19.12). In addition, evidence from twin studies has suggested the strongest genetic predisposition for Class III malocclusion, with concordance in identical twins six times higher than in non‐identical twins for mandibular prognathism.8 Although there is a strong familial occurrence, there seems to be no association with sex, with different modes of transmission in different families or populations.9 Edward Angle, described as the father of modern orthodontics, recognized early in the twentieth century that severe mandibular excess could only be corrected through a combination of orthodontics and mandibular surgery (Figure 19.13).10 The characteristic feature of mandibular excess, and the most common complaint from the ‘Class III’ patient, is the prominence of the chin and lower lip relative to the rest of the face in profile view (Figure 19.14). It is important to distinguish true skeletal mandibular excess from relative mandibular excess. Figure 19.12 The prominent ‘Hapsburg jaw’ and protrusive lower lip of the Hapsburg dynasty is evident in the portraits of (A) Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–58) and (B) Charles II of Spain (1661–1700). Figure 19.13 The ‘chin retractor’ of Edward Angle was a predecessor to the chin cup (chin cap) used by orthodontist in the attempt to correct mandibular excess in young patients by restraining mandibular condylar growth; Angle later recognized the limitations of such appliances. True sagittal skeletal mandibular excess may be due to: True skeletal mandibular excess must be distinguished from relative (apparent) mandibular excess. Conditions in which the mandible appears excessively prominent are: Figure 19.14 The characteristic feature of mandibular excess is the prominence of the chin and lower lip relative to the rest of the face in profile view. The two contrasting heads demonstrate an attractive profile (left panel) and a ‘Class III’ profile with mandibular excess and protrusive lower lip (right panel). (Michelangelo, c. 1516–24, The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.) The aetiology of mandibular excess often results from a combination of relative and true mandibular excess.

Chapter 19

The Mandible

Terminology

Anatomy, morphology and size

Normal Anatomy and Subunits

Morphology

Structural signs

Forward (anterior) mandibular growth rotation

Backward (posterior) mandibular growth rotation

1

Inclination of the condylar head

Forward

Backward

2

Curvature of the mandibular canal

Increased curvature

Straight canal

3

Shape of the lower border of the mandible

Absence of an antegonial notch

Convex lower border and antegonial notch

4

Inclination of the mandibular symphysis (bony chin)

Forward inclination, increased chin projection

Backward inclination, reduced chin projection

5

Interincisal angle

Increased

Reduced

6

Intermolar and interpremolar angle

Increased

Reduced

7

Lower anterior face height

Reduced

Increased

Size and position

Proportional relationship of body to ramus

Sagittal and vertical relationships

Mandibular deficiency

True sagittal mandibular deficiency

Relative mandibular deficiency

Parameter

Normal value (mm)

UK norms (Bhatia and Leighton, 1993)2

US norms (Riolo et al., 1974)1

Male

Female

Male

Female

Total mandibular length

Condylion‐B point

103 ± 4

97 ± 3

117 ± 5

110 ± 4

Condylion‐pogonion

116 ± 5

108 ± 4

131 ± 6

121 ± 4

Condylion‐gnathion

119 ± 5

110 ± 4

134 ± 5

124 ± 4

Condylion‐menton

117 ± 5

108 ± 4

130 ± 5

122 ± 4

Body length

Gonion‐B point

71 ± 5

66 ± 3

80 ± 4

77 ± 4

Gonion‐pogonion

78 ± 4

71 ± 4

87 ± 4

82 ± 4

Gonion‐gnathion

78 ± 4

71 ± 4

86 ± 4

81 ± 4

Gonion‐menton

75 ± 4

68 ± 4

81 ± 4

78 ± 3

Ramus height

Condylion‐gonion

59 ± 4

55 ± 4

66 ± 4

61 ± 2

Articulare‐gonion

48 ± 4

44 ± 4

54 ± 4

50 ± 4

Diagnostic features

Mandibular excess

True mandibular excess

Relative mandibular excess

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree