19

The Future of Facial Plastic Surgery

Peter A. Adamson and Theodore Chen

Science has the ability to surprise, because it marshals the power of both measurement and art. Neither of these pursuits alone could claim to be science, only the two together. Reconstructive surgery is indeed a science, because it strives for precision in measurement while acknowledging a reality that goes beyond measurement—the unique character of the individual. We can expect it to surprise even its practitioners in years to come.1

♦ Past, Present, and Future

“I never think of the future—it comes soon enough.”

—Albert Einstein (1879–1955)

Reflecting on Einstein’s words, at the very least it is bold and presumptive to comment upon the future of facial plastic surgery. One can infer a degree of hubris emanating from any such scribe, if not downright foolishness. But our human imagination is indeed a wondrous trait, and upon request flights of fanciful thought are soon filling the mind to meet the challenge. To share the burden of this pursuit, the authors engaged many recognized leaders and innovators in facial plastic surgery to contribute their musings—it should come as no surprise that there were areas of confluent and diverse opinions. It is well recognized that even the greatest inventors rarely foresee the ultimate impact of their invention or innovation. Edison allegedly believed that the main application of electricity would be the light bulb, which would allow people to read after dark. The brightest of minds, apparently, cannot foresee the future. So where does that leave us mere mortals?

It therefore should come as no surprise that a review of articles in Facial Plastic Surgery and Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery from 1984 to 1988 revealed studies on liposuction, tissue expansion, dermabrasion, fat cell grafting, and polyamide mesh, among others. However, there were no articles on deep plane face lifting, endoscopic lifting, facial transplants, laser skin resurfacing, pulsed light therapies, radiofrequency treatment, or hyaluronic acid fillers—only a few of the advances seen in the past generation. Who could have foreseen these specific developments, and who can truly foresee what the next generation of advances will bring? But let us ponder, if only perhaps to stimulate an idea that will be transformed by one of us into a serendipitous advance for our specialty.

♦ Flashes in the Pan or Foundations for Our Future

“The future, according to some scientists, will be exactly like the past, only far more expensive.”

—John Sladek

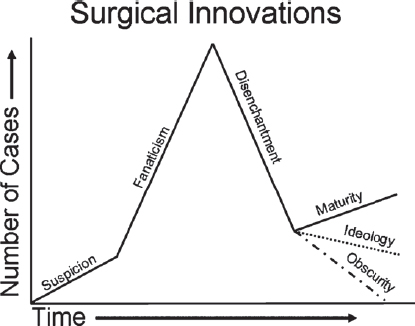

The author of this comment may have been referring to endoscopic, laser, or radiofrequency therapies, which have, respectively, attempted to displace scalpels, sutures, and topical skin treatments from our armamentarium but at a much greater expense. There is no doubt these modalities have their essential applications. Notwithstanding their positive impact on the field of facial plastic surgery, they too have followed the curve of innovation (Fig. 19.1). Many of us remember buccal liposuction; malar, mandibular, and tear trough implants; platysmal excisional techniques; the “push down” rhinoplasty; and a variety of other procedures that once were in vogue but now have much more limited application. This trend will certainly continue, and many of the techniques, tools, and products that we espouse today will be replaced tomorrow.

The unanswerable question is, “Which ones will be flashes in the pan, and which ones will become new foundations for our future?” Each of us will play our individual role in the acceptance, rejection, and application of new technologies and ideas. There is no doubt that some of our current thinking will prove to be false and discarded. Other parts of our future are already here—we just do not recognize it because it has not been discovered yet.

♦ Which Direction To Go?

“How can you research the future? It hasn’t happened yet.”

—Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

Today we have two core philosophies jostling for supremacy in facial plastic surgery: minimally invasive versus open procedures. This began with the controversial external or open rhinoplasty procedure in the 1970s. Studies show the open approach has been accepted by the majority of facial plastic surgeons and has enjoyed increasing application over the past years.2 Its use may now be plateauing, however, and who knows what will be the impact of the novel endoscopic septoplasties now being performed. While we have been opening up the nose, we have been expounding upon the virtues of “closing” our surgical approaches to the forehead, midface, and even the lower face. This modern, minimalistic, innovative, technically savvy trend has held sway for the past 15 years, but it is not without its agnostics who feel that open procedures give a longer-lasting, more secure and natural result that cannot always be achieved by endoscopic approaches. Notwithstanding the sophisticated surgical tools and materials we have at our disposal, it should be stressed there is no substitute for excellent surgical technique, whatever the approach. Although very unlikely in the near future, one might conjure that surgery itself may be minimized with the application of genetic and soft tissue engineering that will create the potential to rejuvenate skin, muscle, and fat biologically without any mechanical intervention.

Fig. 19.1 Surgical innovation curve. (From Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. New York, NY: Free Press; 1962. Adapted with permission.)

♦ Our Search for Beauty

“I have seen the future, and it is still in the future.”

—James Gleick, 2002

Although we know little of the direction that science will lead us, we might presume to possess a little more foresight in how we will perceive beauty, and how this will impact our goal of improving the human visage both reconstructively and cosmetically.

For centuries, we have used the canons of Leonardo da Vinci and others in ascribing mathematical proportions to describe the beautiful face. The Golden Decagon describes the phi ratio of 1:1.618, which represents perfect harmony and which can even be applied to the regional aesthetic units of the face. A more recent concept, koinophilia, which means “love of the average,” emanates from Darwinian theory that states that evolutionary pressures operate against the extremes of the population. We are therefore more attracted to others of the opposite sex with “average features.” This average is determined uniquely for each person by the constant collection of facial impressions each sees in his or her own environment. The composite human face so encrypted in our mind becomes the most attractive to that specific individual.

As our world becomes a global village with greater travel, migration of people, and interracial reproduction, the paradigm for the average, attractive face is changing. This will undoubtedly continue for the generations to come resulting in increasing attraction by all of us to nonhomogeneous racial features as there is more blending of distinct racial stereotypes. There will be a globalization of beauty. At the same time, there will be an increased acceptance of ethnicity as we live side by side with different races and individuals who still express homogeneous racial features in their appearance. Political, religious, and ethnic realities will likely counter this trend.

It is also recognized that beauty, in contradistinction to attractiveness, is determined by facial features that not only reflect averageness and symmetry but also importantly reflect estrogen in females and testosterone in males. This implies larger eyes, smaller nose, fuller lips, and narrower chin for females, and smaller eyes, larger nose, longer thinner upper lip, and wider jaw for males. Needless to say, much of our work is directed toward procedures that enhance these features: forehead lifting, eyelid lifts, rhinoplasty, lip enhancement, and facelifting, to name but a few. These procedures not only make a woman look more youthful but also more feminine. However, caution must be observed. If any feature is overdone so as to look unnatural, the genuineness of character is lost and the overall effect of the procedure negated. Knowing this, we can expect an ever-increasing effort to achieve natural appearances and a move away from treatments that create trendy looks that are overdone and unnatural. We will also focus more on the hormonal effects of estrogen and testosterone on women and men and seek interventions that will enhance these effects in them, respectively.

Fig. 19.2 Rhesus monkey Canto (left), on a restricted diet, and Owen (right), a control subject on an unrestricted diet. Both animals are part of long-term, NSF-funded research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison studying the links between diet and aging in monkeys. (Courtesy of Jeff Miller, University of Wisconsin, Madison.)

As facial plastic surgeons, we should be aware of trends and advances in other fields that may impact upon us. For example, there is increasing interest in, but not yet enough research to support, the value of restricting caloric intake by up to 20 to 30% to increase both average and maximal life span.3 There is some support for this in monkey studies (Fig. 19.2). Notwithstanding the current obesity epidemic in North America, would such a trend provide new opportunities for facial rejuvenation and volume restoration in a growing number of people?

Dramatic new cosmetics from the fashion world may also impact thinking about skin care and interventions. For example, at Chanel attempts are being made to apply artificial skin technology to cosmetics.4 Some say that within a few years, foundations and treatment products will be able to “read” the skin using tiny “enviro” chips to determine the level of moisture, coverage, and texture required. In addition, color cosmetics such as lipsticks and shadows will adapt their hues to complement skin tones in all kinds of lighting, similar to some spectacles today.5

♦ Genetic and Tissue Engineering

“Without expectations, there is no future, only an endless present.”

—Francois Jacob, Nobel Laureate in Medicine

We would all agree that a greater fundamental knowledge of the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that cause aging would aid us in prevention and management of the aging process. Our current understanding is rudimentary, and we will not see any paradigm shifts in treatments until much more is learned. However, the Genome Project has built the foundation on which we can pursue studies leading to tissue engineering of a variety of tissues, potentially including skin, fat, bone, cartilage, and muscle.

For example, tissue engineering of human septal cartilage has been performed. A small biopsy of septal cartilage can be used to create neocartilage that can be shaped as desired by using an absorbable poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) polymer scaffold. This neocartilage has been tested and has essentially the same biomechanical properties as native septal cartilage.6 Applications would include facial reconstruction and revision rhinoplasty, which could eliminate the need for alloplastic implants, rib grafts, and so forth.

There has been an increasing amount of research being performed on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are harvested from bone marrow. In one study, the authors were able to differentiate the MSCs into adipose tissue.7 Currently, we know that fat injections using mature adipocytes are somewhat unpredictable and sometimes temporary. Using preadipocytes is problematic as well. Preadipocytes have a reduced ability to proliferate, unpredictable variability based on anatomic sites, and limited availability. Moreover, with regard to primary preadipocyte cultures, differentiation capacity is clearly donor-dependent and decreases significantly with age. However, the adipocyte-forming capacity of MSCs is similar in both young and old donors; it is possible that MSCs may constitute a better material for soft tissue regeneration than do preadipocytes. The same study also demonstrated that MSCs could be mounted onto PLGA injectable spheres. The adipo-MSCs differentiate into adipocytes on PLGA spheres, and adipo-MSCs on PLGA spheres formed adipose tissue in vivo. For larger defects, the MSCs could also be mounted onto a scaffold to create a three-dimensional soft tissue filler. Furthermore, the same MSCs can be differentiated into osteocytes or chondrocytes if needed.

Gene therapy is also being researched for the treatment of skin cancers. Currently, our primary treatments are anatomic ablative techniques, that is, surgery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, radiation, and topical ointments. Treating genetic problems with anatomically based modalities could become obsolete. In particular, there is extensive research being done on gene therapy for melanoma.8 It is well recognized that all cancers, including head and neck, reflect complex genetic interventions. How close are we, really, to genetically engineering the cure for those tumors?

Although cloning is possible, having been successfully performed in animals, the ethical issue surrounding human cloning will likely obstruct this development, except by renegade groups. This obviously would pose a substantial ethical dilemma for our profession and for society.

♦ Facial Reconstruction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree