3

The Facelift: A Guide for Safe, Reliable, and Reproducible Results

William H. Truswell IV

The cornerstone of surgical rejuvenation of the aging face is the facelift operation. The method the surgeon uses to perform this procedure will be determined by many factors. The most important consideration is that the surgeon does a procedure with which he or she is comfortable and at which he or she excels. Above all, experience affects outcome. In the beginning of one’s practice and experience, a solid approach to sub–superficial musculoaponeurotic system (sub-SMAS) lifting will produce very good results and happy patients. As time passes, the surgeon will gain confidence both mentally and manually with his or her surgical technique and outcomes. This becomes the time to move into more advanced and technical lifting.

Residency and fellowship training, reading texts, listening to lectures, and attending courses certainly provide the scientific and procedural information needed to perform facelifting. Operating over time on the myriad of different facial types, however, imparts the knowledge of what the tissues feel like, how they dissect, how they heal, and how they behave over time after surgery. The emerging facelift surgeon learns through his or her practice how to treat the full spectrum of patients from those with heavy faces and thick, type-III-and-beyond skin, substantial fascia, short necks, and an abundance of fat to those with ultrathin faces and thin, type I skin, tissue paper–like fascia, long necks, and a complete paucity of fat. It is worth repeating that as the surgeon performs more facelifts, his or her confidence grows manually through muscle memory, intellectually as different facial types are encountered and their outcomes studied, and emotionally through both the praise of grateful patients and the problems of the difficult ones.

The first section of this chapter will describe the author’s standard for facelift patients from first contact to final farewell and his approach for a sub-SMAS facelift in the uncomplicated face, which over the years has allowed reliable, reproducible results and happy patients. The happy patients make the practice grow.

♦ The Goal: A Happy Patient—The True Measure of Success

First Contact

The goal to which one must strive is more than a satisfied patient; it is a happy patient. This outcome, the happy patient, will be the key that makes one’s practice grow and prosper. To achieve this, the surgeon must think beyond the technicalities of surgery. There needs to be a global approach to the cosmetic surgery patient. The process begins with the prospective patient’s first contact with the office. The voice, manner, and style of person answering the telephone sets the tone for all that follows. The receptionist must be warm and welcoming, be able to answer questions about the surgeon and his or her experience and qualifications, the practice and its history, and general questions about the procedures done. Clinical questions may be diverted to a nurse or technician, but they too must have these same people skills. A letter is sent out to the patients once they have scheduled a consultation thanking them for making the appointment. The letter tells them what to expect when they arrive at the office and our commitment to patient education. We include a registration form for them to fill out and bring with them. Other enclosures can include a custom practice brochure or brochures from the academy.

The Setting

The office setting will be the first physical impression the patient has of the practice. The reception area and waiting room must be warm and inviting, a place where one will be comfortable and happy to sit for a while. The waiting time should be brief. Information forms should be short, not encyclopedic, or the information could be taken at the patient coordinator’s interview. All that happens before the patient meets the doctor reflects onto the surgeon, and the patient is forming an opinion of the practice and the surgeon starting with the first contact (Fig. 3.1).1

Fig. 3.1 The waiting room should be warm and inviting, a place where one would not mind waiting a while.

The Staff

The entire office staff must be friendly and nurturing. They will make the patient feel that she or he will be cared for and cared about. They should dress in a manner that is “upscale” and their grooming must be impeccable. This atmosphere will have the patient feeling that she or he has chosen the best place for his or her needs and desires to be met.

The patient coordinator, nurse, or manager will greet the patient and take digital photographs. The photographs must be standardized for all patients as to position and lighting. This is best done in a dedicated room. The pictures become an integral part of the medical record and should be treated as such. Pictures are taken in frontal, 45 degrees to each side (oblique), and both lateral positions. They are all in the Frankfort horizontal plane. They should also be taken in each position with the patient’s hair in its natural style and with the hair up and any high collar rolled down, and earrings and necklaces removed. Standard positions for facelift surgery are full face and neck, right and left oblique, and full lateral right and left. It is important to see the entire ear and all of the neck. This becomes the preliminary step in patient education. At this juncture, a discussion ensues about what the patient’s desires are. A skilled coordinator will discern what the patient needs and gently indicate what the doctor may suggest. She will also be able to determine how realistic the patient is and if the patient is a good candidate for the surgery. She will then brief the surgeon about the patient and what he or she may expect.

♦ What Are We Trying to Achieve? The Refeminization of the Female Face

The facelift surgeon should have an understanding of what he or she is trying to achieve. In different parts of the country, patient populations may very well have different ideas about how they wish to look after their surgery. These ideas will also vary within locales.

In western New England, for example, patients have told me for more than 30 years that they do not want to look “done.” They want a natural, nonoperative appearance and they often fear being approached by friend or acquaintance with the comment, “You had a facelift.” Celebrities they see in the media as well as people they have seen in traveling to more cosmopolitan areas of the country often appear to them as “overtightened” and not looking like themselves. I answer this worry simply by showing them preoperative and postoperative photographs of my patients. It is necessary for the surgeon to understand the style of the demographic where he or she practices.

Unfortunately, as time passes, the soft, lovely, feminine face of youth becomes more masculine (Fig. 3.2). Men have low brows, and a woman’s eyebrows descend. Men have thin lips, and a woman’s lips lose volume. Men have square jaws and heavy necks, and as jowls and wattles appear, the feminine jaw line squares off and the neck tissue falls. Men also have coarser skin, and a woman’s skin will coarsen, too. We as surgeons cannot realistically make a 60-year-old face appear to be 40 or even “take 10 years away.” I believe the realistic expectations for the surgeon and patient are encompassed by the words soften, refresh, rejuvenate, and refeminize. This is done by lifting the soft tissues of the face and neck, restoring lost volume, and revitalizing aged, sun-damaged skin to create that more youthful and feminine appearance of youth (Fig. 3.3). The patient will know the kind of work the surgeon does from the photographs shown during the consultation. These should not be the most beautiful and successful cases but a collection of faces from those of average appearance to the very attractive, including heavy faces, thin faces, and different skin types. This will present an honest view of what is achieved by the hands of the surgeon.

♦ Patient Selection

Patient selection involves the physical, the emotional, and the psychological assessment of the prospective candidate.1–3 Emotional stability is a must before surgery is undertaken. Recent spousal loss due to separation, divorce, or death causes an emotional wound that must be well healed before a facelift is done. This operation will not fill the void or lift the spirits of the griever. Similarly, psychological disorders such as a bipolar disorder must be in control as well. Lastly, the physiognomy of the person must be well suited to receive reasonable results. The morbidly obese face will not have a pleasing or a lasting result.

Fig. 3.2 The masculinization of the aging feminine face.

Ideally, every patient would be late middle age, normal weight, type I or II skin, with a long elegant neck, good facial bone structure and facial proportion, and in good health. In the majority of cases, however, this is not the situation. The facelift surgeon will sample the whole sea of humanity. It is important, of course, that the patient’s health is such that it will not bring risk to the procedure. Medical conditions such as hypertension and diabetes must be stable. Medical clearance should be obtained for the patients preoperatively. The overweight patient should be asked if she is planning to lose weight. Significant weight loss should precede the surgery for optimal results. Facial balance is also important. A recessive chin when corrected will enhance the results of the procedure. Sometimes patients will only want or perhaps can only afford to have the facelift done when in reality they need full facial rejuvenation. It is imperative that they understand and acknowledge the imbalance that will occur between the rejuvenated lower face and the untreated upper face. Both the patient and the doctor must have realistic expectations.

Fig. 3.3 (A) Before and (B) after endoscopic brow and facelifting: restoration of a more youthful and feminine countenance.

♦ The Consultation

All this attention to detail comes before the patient meets the doctor and should lift her or his expectations. The consultation is the opportunity for the surgeon to convince the patient that there is no reason to look further. It is the start of a very special doctor-patient relationship. It is the time the surgeon will be determining the true motivation of the patient. The attitude, appearance, and personality of the physician will lead to a successful surgery booking. In a relatively short period of time, he or she will listen to the patient’s concerns, evaluate the face, explain the options, demonstrate with pictures his or her typical results, perhaps do computer imaging, and enumerate potential problems. Computer imaging is an opportunity for the surgeon to demonstrate the goals of the surgery to the patient by altering the patient’s photograph. It must be understood that what is being demonstrated is not an exact representation of the results of any surgery but a simulation of what could be achieved. It is wise to make the imaging somewhat less than the actual results of the surgery.

Preoperative and postoperative photographs of patients who underwent similar surgery are reviewed with the patient. This is an opportunity for the patient to see the kind of results from the hands of her chosen surgeon. The pictures should not be just of the best-looking patients with spectacular results but of faces from all walks of life. Not everyone is beautiful, and the patient should be able to relate personally to some of the pictures. The photographs should be at various intervals after surgery. We show patients at 1 day after, 1 week after, to several years after surgery. The patient should understand the issues of healing and swelling and have a feeling for the natural aging process after facelifting. The patient should come away thinking that there is no reason why this surgeon alone should not take scalpel and scissor to her or his face and change her or his appearance. This task may or may not seem either daunting or arrogant; however, it must be done gently, in a warm and friendly fashion, taking the patient’s concerns and fears into consideration.

The consultation is the second and the most important step in patient education. When the patient has a good understanding of what can and cannot be achieved, what the sequelae and possible complications are, and what the operation and postoperative period entail, the entire experience will be smoother with less patient anxiety, more patient compliance with instructions, and realistic patient expectations. The patient should feel that all of their questions and worries are answered, should have no doubt that this surgeon is the best choice, and should never feel rushed.

The surgeon must elicit a medical history from the patient. All previous surgeries including cosmetic procedures need to be explored. It is good to know, in the case of cosmetic surgery, if the patient’s expectations were met and if they were happy with their results. This may give an indication of their attitude, goals, and motivation. It should be considered a “red flag” if the patient expresses anger or regret. This would need to be explored thoroughly. The surgeon should be alert for possible personality disorders, the presence of body dysmorphic syndrome,4 and any unrealistic expectations the patient may have. The existence of significant personality disorder or body dysmorphic syndrome would preclude surgery. If unrealistic expectations cannot be eliminated through patient education, any patient harboring them is not a good candidate for a cosmetic procedure. This is also the time to learn the patient’s medical history. It is necessary to know what chronic medical problems the patient may have and what prescription and over-the-counter medications are being taken. Any allergic history to medications and latex must be elicited.

The face, head, and neck should be examined carefully. Assessment of the skin type, solar damage, lesions, rhytides, and elasticity are noted. It is important to note the skin type, the amount of sun damage, and the degree of elasticity in each patient. Skin with severe elastosis and/or significant sun damage may very well benefit from concurrent or sequential resurfacing. In these instances, resurfacing either by laser or peels greatly adds to the result of facelift surgery. The CO2 laser is uniquely beneficial. Facelifting repositions and recontours the soft tissues of the face and neck, and laser resurfacing, in addition to reducing rhytides, removing lentigines, and improving skin texture, will tighten the skin itself and stimulate the formation of new collagen.

The amount and location of subcutaneous fat needs consideration. The heavier faces, particularly of those patients in need of weight reduction, will have a less than ideal outcome. It is imperative to let the patient know and be certain she understands this limitation. These individuals with heavy skin and subcutaneous tissues will not enjoy a sleek and elegant look from surgery. They will look refreshed, rejuvenated, and, in the case of women, refeminized. They must be taught the realistic outcome of the operation in their individual circumstance. They also must understand that recurrence of aging will be sooner for them than in the thinner, more esthetic face. Using added platysmal support such as the Giampapa suture5 or securing the elevated platysma with barbed threads to the mastoid fascia may prolong and enhance the effect of the surgery. The surgeon should also assess the use of ancillary procedures such as malar augmentation and a chin implant that could add to the outcome. Again it is best to have a committed weight loss before proceeding with facelifting. If this is not to be, the surgeon needs to have the patient completely understand the likely outcome and maintain realistic expectations.

The position of the hyoid bone is important. A low hyoid will interfere with developing a deep cervicomental angle. Ptotic submandibular glands are visible especially in thinner necks. These attributes must be pointed out to the patient preoperatively. These issues can be demonstrated to the patient with a mirror and imaging. It is important when imaging these patients that the consultant does not demonstrate a deep cervicomental angle where it cannot be achieved nor eliminate the submandibular gland bulge when this cannot occur.

Midface ptosis also must be evaluated and discussed. Many people assume that the standard facelift will also correct this problem. Different approaches to this region include surgical midface lift, malar and/or submalar implants, and barbed thread lifts. These alternatives are covered in other chapters in this text.

Patients often think that facelift means the entire face, the eyelids and forehead included. The entire face should be evaluated and different options discussed. The surgeon must be sensitive to the fact that whereas he or she would like to perform brow lifting, blepharoplasty, chin implant, and facelift, the patient may only be able to afford one procedure. This should be the one that would address her major concern.

Near the end of the consultation, the surgeon will review the probable sequelae and possible complications of the operation. This discussion should be frank but not overwhelming. It is the final part of patient education and an important one. Bruising, swelling, numbness, stiffness, and soreness are all probable. Complications do occur from time to time. It is necessary that patients understand that though unlikely, one could happen. They also must be assured that if one occurs, it will be remedied.1,6,7

♦ The Closing and Booking

In this author’s opinion, financial and scheduling discussions should be done by a scheduler, patient coordinator, or office manager. This meeting is also very important. It is the third step in patient education. It should be conducted in a comfortable and private setting. When handled correctly, it can in many instances lead a hesitating person into booking the procedure. Financial disclosures can be awkward for some individuals and must be handled in a sensitive manner. Today many patients need to finance their surgery. It is recommended that the physician’s practice not extend credit. There are several companies that offer financing for cosmetic surgery. Patients can in most circumstances get better rates with a personal or equity loan from their local bank. The patient should be given the fee in writing and a photocopy retained in the patient’s chart.

♦ Preoperative Visit and Instructions

Three to 4 weeks prior to the surgery date, the patient returns to the office for preoperative instructions, the fourth step in patient education. This is also done in a nonclinical, attractive setting by one of the nurses. Patients often express concerns to the nurse that they did not disclose to the doctor. They also listen differently at this meeting than at the initial consultation. The nurse reiterates the nature of their operation and the preoperative and postoperative periods. All of their questions are answered. The discussion should include the nature of dressings and drains, bruising and swelling, what could arise that would necessitate a call to the office, and what they might expect that should not cause a worry. Realistic outcomes are reviewed. It is generally a good idea if the physician is in the office at this time. If there is any misunderstanding on the part of the patient, the surgeon can be available to clarify concerns. Postoperative instructions are delivered verbally and in writing to the patient along with required prescriptions. Consents for surgery and anesthesia are obtained. Preoperative laboratory tests including an EKG and a physical examination are arranged. Fees are collected. Lastly, the nurse records the name of the person who will be staying with the patient on the night of surgery if she will be going home. If necessary or desired, a private duty nurse is arranged for.

♦ The Day of Surgery

On the day of surgery, the patient should be personally greeted at once by the nurse or staff member. She should change clothes in a quiet and private room. The room should be warm with soft lighting and soft music. If the surgeon has his or her own operating suite, there will be more control of the environment than in a hospital. All personnel should behave in an attentive manner designed to calm and reassure the patient that she is the sole object of their concentration and care. Recovery should also be quiet and private with constant attendance and monitoring. If this is a private facility, it must be accredited by an organization like the Accreditation Association of Ambulatory Health Care.

The patient changes into a surgical gown. The surgeon greets the patient in this nonclinical atmosphere and answers any last-minute questions. The face is marked here with the patient in a sitting position. The intravenous line may be started here or in the operating room. After marking is completed, the patient is asked if she needs to use the bathroom one last time and is then brought into the operating room. Here she is helped onto the operating table. A warming blanket is placed over her. The intravenous is started if not already done. She is connected to blood pressure, cardiac, and pulse oximetry monitors. Blood is drawn for the preparation of platelet gel if used. Her hair is put into pigtails around the incision sites. Music is softly playing, she is gently sedated or inducted and prepped and draped. The atmosphere is kept subdued and soothing.

♦ Postoperative Care

If the patient is going home or to a hotel on the night of surgery, she will require a constant companion to stay with her. This person must have the necessary telephone numbers of whom to call for questions or in case of an emergency. Preferably, a private duty nurse will be hired. The evening of surgery, either the doctor or the nurse will call the patient to see how she is doing and to answer any questions. The next day, the patient is seen for dressing change or removal. We remove the dressing and wash out and blow-dry the patient’s hair. The patient is given an elastic sling to wear for the ensuing week. Postoperative appointments are made. The patient will return at varying intervals and times depending on what ancillary surgeries were done and how the postoperative course is progressing. Four to 8 weeks later, the patient returns for a cosmetic “make-over” with an esthetician, and postoperative photographs are taken.

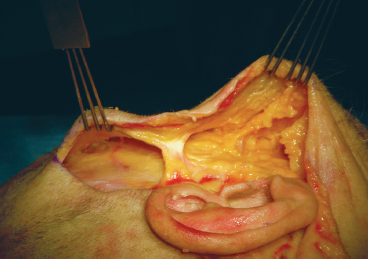

♦ Pertinent Anatomy

A keen knowledge of facial anatomy is an obvious prerequisite to performing facial surgery. This topic was covered in depth in Chapter 2. The SMAS is the structure that will be exposed, incised, divided, lifted, and plicated or imbricated in some fashion in facelift surgery. It has intimate and fixed relationships with the motor and sensory nerves of the face as well as with much of the major vasculature. The SMAS encompasses the muscles of facial motion and their investing fascia. This is the layer that is manipulated and repositioned to rejuvenate the aging face. It overlies the parotid fascia, although it is considered by some to incorporate this layer.8,9 As it extends forward, it becomes clearly associated with the facial muscles first at the zygomaticus major. In the more anterior cheek, it appears thinner and less well defined. In the neck, it is continuous with the platysma muscle. In the scalp, the SMAS is the galea aponeurotica, and as it descends into the temple region it is the superficial temporal fascia (temporoparietal fascia). It becomes entwined and intimately involved with the multiple fascial layers at the zygoma (Fig. 3.4).

The SMAS overlies the major vessels and nerves of the face. Smaller branches of these structures extend up to the dermis. Elevating the skin and subsequently the SMAS interrupts these connections. This results in the temporary hypoesthesia all facelift patients experience in the periauricular area after surgery.

There are fibrous connections between the dermis and underlying SMAS known as fasciocutaneous ligaments. These ligaments are significant in that when the SMAS is elevated and repositioned to create a rejuvenated appearance, the skin is drawn along with it. Putting all the tension of lifting on the SMAS and not the skin overcomes the problems encountered in years past when facelifts were essentially done by creating long skin flaps that were lifted and pulled with tension to points before and behind the top of the ear. The viscoelastic properties of skin are such that these skin tension techniques endured short life spans and often resulted in wide scars. There are also two firm attachments of the skin to the underlying bone. These osteocutaneous ligaments are the zygomatic cutaneous ligament, McGregor’s patch, and the mandibular cutaneous ligament.10

Fig. 3.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree