CHAPTER 13 The Direct Lateral Approach

KEY POINTS

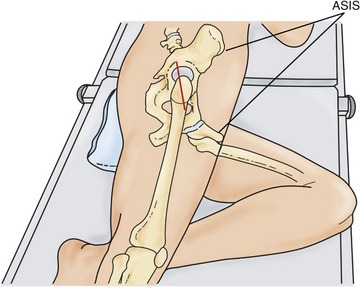

The operation can be done either with the patient in the supine position with a bump placed under the ipsilateral sacroiliac joint or in the lateral decubitus position.

The operation can be done either with the patient in the supine position with a bump placed under the ipsilateral sacroiliac joint or in the lateral decubitus position. The skin incision should begin several centimeters above the palpated tip of the greater trochanter and extended distally 10 to 15 cm along the midline.

The skin incision should begin several centimeters above the palpated tip of the greater trochanter and extended distally 10 to 15 cm along the midline. The tensor is split the length of the incision from distal to proximal extending posteriorly into the gluteal fascia. This helps eliminate the potential problem of a tight posterior sling, which can make dislocation difficult.

The tensor is split the length of the incision from distal to proximal extending posteriorly into the gluteal fascia. This helps eliminate the potential problem of a tight posterior sling, which can make dislocation difficult. With the leg externally rotated, the medius and minimus are released independently from their most inferior borders to the anterosuperior corner of the trochanter leaving 5 mm of tendon behind for reattachment.

With the leg externally rotated, the medius and minimus are released independently from their most inferior borders to the anterosuperior corner of the trochanter leaving 5 mm of tendon behind for reattachment.The direct lateral approach was first described by Kocher in 1903. It was popularized in 1982 by Hardinge,1 who expanded on the key points of several earlier methods for approaching the hip laterally. The approach offers several advantages for hip arthroplasty, including retention of the posterior capsule with a reduced likelihood of dislocation. It also provides excellent exposure of the acetabulum without iatrogenic flexion of the pelvis, which can lead to problems in achieving correct acetabular placement.2,3 The approach has gained wide support; however, many surgeons remain concerned about the questionable injury that the approach inflicts on the abductor muscles. Lester Borden is credited with accurately describing the anatomy of the gluteus medius and minimus attachments and providing the basis for anatomic repair procedures. With improved repair techniques, concerns about persistent limps and heterotopic ossification were thus lessened.3–8 The approach described by Borden has been further modified to eliminate the release of the vastus muscle, and for several years it was referred to as the anterolateral approach. This name has now been dropped in view of the development of another muscle-sparing approach to the hip, which has also been described as “anterolateral.” The approach described here, then is more currently named a modified version of the direct lateral approach.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The direct lateral approach can be used for most routine primary total hip procedures (both cemented and cementless) and for resurfacing of the hip.9 It can also be extended distally for extensive visualization of the femur.

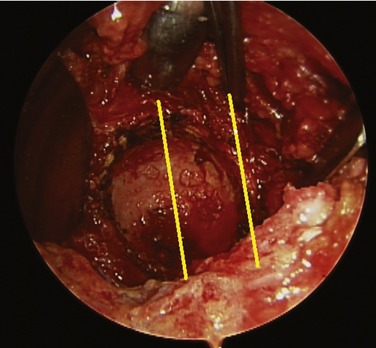

This approach is contraindicated in patients who have had prior proximal femur fractures that have healed in a flexed alignment (Fig. 13-1). Leg lengthening of more than 2 cm is difficult using this approach because it is difficult to repair the hip abductors when the hip is lengthened.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

How much does the leg need to be lengthened? If it must be lengthened more than 2 cm the direct lateral approach should not be used.

How much does the leg need to be lengthened? If it must be lengthened more than 2 cm the direct lateral approach should not be used. Are there any bony deformities or soft tissue deficits that will affect the reconstruction? For example, flexed femoral malunions are better approached posteriorly.

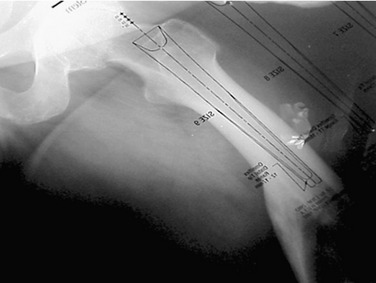

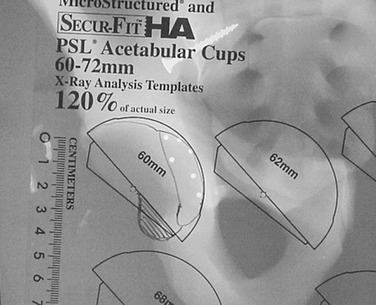

Are there any bony deformities or soft tissue deficits that will affect the reconstruction? For example, flexed femoral malunions are better approached posteriorly.The second phase of planning is based on a working knowledge of the goals of prosthesis placement to optimize postarthroplasty hip function and maximize the recovery rate. Bony landmarks that can be identified intraoperatively are noted on preoperative radiographs to allow optimal prosthesis placement (Fig. 13-2)2,10,11:

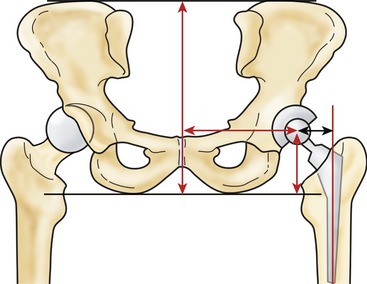

The acetabulum should be medialized to the floor of the fovea to reduce the body weight lever arm and lower demand on the abductor muscles (Fig. 13-3).

The acetabulum should be medialized to the floor of the fovea to reduce the body weight lever arm and lower demand on the abductor muscles (Fig. 13-3). The center of rotation should be restored so that the inferior edge of the socket corresponds with the acetabular outlet to aid in restoring the working length of the abductors.

The center of rotation should be restored so that the inferior edge of the socket corresponds with the acetabular outlet to aid in restoring the working length of the abductors. The abduction angle should approximate 45 degrees. The prominence of the inferior cotyledons can be used as a guide to abduction (Fig. 13-4).

The abduction angle should approximate 45 degrees. The prominence of the inferior cotyledons can be used as a guide to abduction (Fig. 13-4). The version should match the normal opening angle of the native joint. A line connecting the palpated sciatic notch with the posterior acetabular wall is parallel to the normal opening angle of the socket.

The version should match the normal opening angle of the native joint. A line connecting the palpated sciatic notch with the posterior acetabular wall is parallel to the normal opening angle of the socket.TECHNIQUE

Skin Incision

SURGEON: The skin of the hip should be palpated to identify bony landmark locations and generate an outline of the greater trochanter to be drawn on the skin. The skin incision is started 2 to 4 cm above the anterior tip of the greater trochanter and carried distally along the anterior aspect of the femoral shaft. An incision length of 10 to 15 cm is adequate for most patients. In obese patients, the incision may need to be extended to allow an unencumbered approach for femoral broaching. When the supine position is used, the incision is direct, straight along the middle of the femur, and extends several centimeters cephalad to the trochanter. When the lateral decubitus position is used, the incision is angled slightly posterior (Fig. 13-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree