CHAPTER 30 Tarsal Coalition

EXAMINATION AND DECISION MAKING

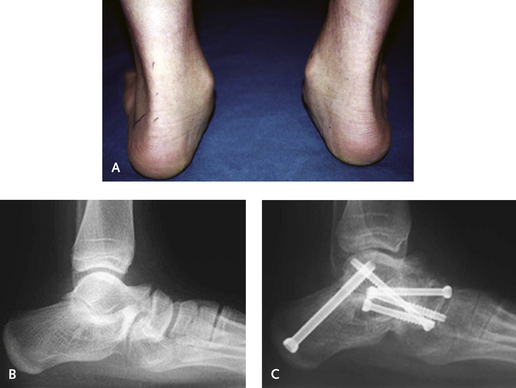

Tarsal coalition is one condition that the clinician can diagnose standing at the door of the examination room. Typically, when the patient is seated, the foot normally drops into a position of equinovarus. With a rigid hindfoot, the foot is held in valgus; if the deviation is unilateral, it is particularly easy to diagnose. Examination of the foot while the patient is standing, walking, sitting, and lying down is recommended. When a person with a normal foot is sitting, a natural equinovarus posture is present in the foot as it relaxes. This is not the case with a tarsal coalition because the foot is held in a more rigid position of neutral dorsiflexion with slight valgus (Figure 30-1). The peroneal tendons often are visible because of ongoing contraction, but true peroneal “spasm” does not occur. The peroneal musculature may be tender and certainly tight as a result of subtalar joint irritation, but true spasm does not occur. The decision for surgery, and for a specific type of surgery, is based on the flexibility of the foot, the presence of arthritis, the type of coalition, and function of the remaining foot. The spectrum of clinical deformity associated with coalition is very broad, and when rigidity is present, marked compensatory changes may be seen in the hindfoot and forefoot (Figure 30-2).

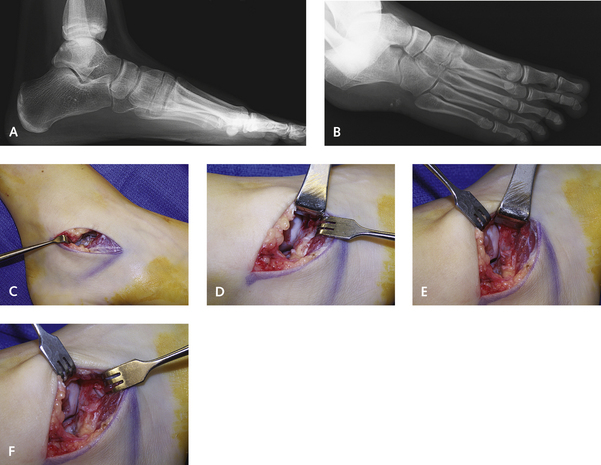

It is not easy to examine the hindfoot for true motion when the peroneal tendons are contracting. In patients who have severe stiffness, determination of how much true motion is present in the foot and how much the peroneal muscles are limiting subtalar motion is worthwhile. If the peroneal muscles are tight, I block the peroneal nerve at the fibular neck with a short-acting local anesthetic and then reexamine the foot. After peroneal nerve blockade has been achieved, the foot frequently is much easier to examine, the rigidity of the hindfoot previously noted is no longer present, and the surgery can be planned correctly. A diagnostic blockade of the subtalar joint or the sinus tarsi is not very helpful in these patients. Sometimes the coalition is not visible on radiologic evaluation, and, rarely, even with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scanning, the coalition is difficult to visualize (Figure 30-3).

Whenever possible, I attempt resection of a coalition rather than an arthrodesis. Certainly, in the presence of arthritis of the hindfoot joints, an arthrodesis will be necessary, but in my experience, the arthrodesis is overused as a treatment modality in both adults and children. If arthrodesis is performed, a triple arthrodesis is indicated only with extensive deformity, which includes the subtalar and transverse tarsal joints as well as arthritis. A triple arthrodesis is therefore not required for correction of a middle facet coalition unless additional disease is present in the transverse tarsal joint. An interesting example of this problem, occurring in an adolescent patient with severe bilateral coalition, is presented in Figure 30-4. Not only was the hindfoot fixed in valgus, but the midfoot also was severely abducted. This was a double middle facet–calcaneonavicular coalition (see Figure 30-4). Rarely do I perform an arthrodesis for a calcaneonavicular coalition, even in adults.

It has been stated that “a middle facet coalition in a child can be excised if it involves less than 50%.” I do not agree with this statement, and regardless of the extent of the coalition, I perform a resection of the entire coalition. The outcome with resection of the middle facet coalition depends more on the flexibility and deformity of the remainder of the foot. The problem with a complete coalition is not with the ability to resect it but with the adaptive changes that have taken place over time in the subtalar joint and the remainder of the foot (Figure 30-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree