Chapter 28 Syphilis

1. What causes syphilis?

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, ssp. pallidum, which belongs to the order Spirochaetales. T. pallidum ssp. endemicum is a subspecies that causes bejel, or endemic syphilis. Other pathogenic treponemes for humans include T. pallidum ssp. pertenue, the cause of yaws, and T. carateum, the cause of pinta. There are other Treponema species that infect other animals or are free-living. Since 2000, there has been an increase in the number of reported cases in the United States, with 11,466 cases of primary and secondary syphilis being reported in 2007, which is a 15.7% increase when compared to the figures from 2006.

2. Describe the morphologic appearance of T. pallidum.

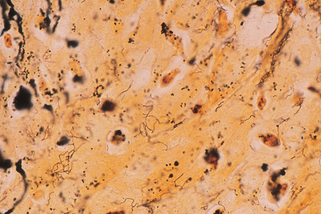

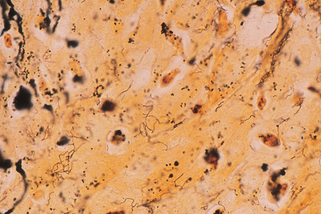

T. pallidum is a delicate spiral bacterium that measures 6 to 20 mm in length and 0.10 to 0.18 mm in width (Fig. 28-1). Because of the narrow width, it is not visible by normal light microscopy and must be visualized by darkfield microscopy, by silver stains (i.e., Warthin-Starry or modified Steiner stains), or by immunoperoxidase stains (Treponema). The spiral coils are regularly spaced at a distance of about 1 mm. The typical spirochete has 6 to 14 coils. The organism reproduces by transverse fission.

3. Where did syphilis originate?

The origin of syphilis had been a point of great debate among experts, with some authorities favoring a New World origin because of an epidemic of syphilis that ravaged Europe in the last decade of the 15th century, when it was referred to as the “Great Pox” (as opposed to smallpox). Because this epidemic coincided with the return of Columbus from America in 1493, this suggested that it was imported from the West Indies. Of interest, Columbus himself is thought to have died from syphilitic aortitis. Other authorities maintained that it had always been present in the Old World. Studies on skeletal remains clearly demonstrate that while treponemal disease was present in the Old World, epidemic syphilis was imported from the New World.

Figure 28-1. Biopsy of secondary syphilis demonstrating numerous spirochetes in the epidermis (Warthin-Starry stain, ×1000).

Tognotti E: The rise and fall of syphilis in Renaissance Europe, J Med Humanit 30:99–113, 2009.

4. How is syphilis transmitted?

Syphilis is most commonly acquired as a sexually transmitted disease but also may be acquired congenitally (see Chapter 57) or, rarely, by blood transfusions. The organism is very fragile and easily killed by heat, cold, drying, soap, and disinfectants. Since the spirochete is so fragile, the possibility that an infection could be acquired from a toilet seat is statistically very remote.

5. What are the chances of getting syphilis from having sexual intercourse with an infected individual?

6. Following inoculation, how long does it take for the primary chancre to appear?

Experimental study on both rabbits and human volunteers has shown that the appearance of the primary chancre is related to the size of the inoculum. The primary chancre normally appears in 10 to 90 days, with the average time being about 3 weeks. The organism reaches the regional lymph nodes within hours.

7. Describe the typical Hunterian chancre.

The classic Hunterian chancre develops at the site of inoculation as a painless ulcer with a firm, indurated border (Fig. 28-2). The size may vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. Associated unilateral or bilateral, painless, regional, nonsuppurative lymphadenopathy develops in 50% to 85% of patients approximately 1 week after the appearance of the primary ulcer. It is important to realize that up to 50% of all chancres are atypical. Painful ulcers, multiple ulcers (Fig. 28-3), secondarily infected ulcers, and nonindurated ulcers are variations on the classic chancre.

Figure 28-3. A typical presentation of primary syphilis demonstrating two chancres.

(Courtesy of William James, MD.)

Lee V, Kinghorn G: Syphilis: an update, Clin Med 8:330–333, 2008.

8. Do syphilitic chancres occur on sites other than the genitalia?

Extragenital chancres occur in 5% of all cases of primary syphilis, although the incidence may be as high as 10%. The most common extragenital sites are the lip, which is associated with oral sex, and anus, which is associated with anal intercourse. Anal intercourse may also produce rectal or colonic chancres as high as 20 cm into the bowel. Other reported sites include the tongue, tonsil, finger, thumb (Fig. 28-4), eyelid, chin, nipple, umbilicus, axilla, and even the lower limb. A high index of suspicion is required to diagnose extragenital chancres.

Figure 28-4. Extragenital chancre of syphilis on the thumb.

(Courtesy of the teaching files of Fitzsimons Army Medical Center.)