(1)

Department of Neurosurgery Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, Saga, Japan

Keywords

Foramen magnumPosterior paramedian approachesForamen magnum meningiomaC2 ganglion-sectioning epidural approachLower clival chordoma16.1 Introduction

The atlanto-occipital joint lies in the lateral portion of the foramen magnum, which along with the vertebral artery (VA) forms obstacles to approaches that pass through the lateral foramen magnum. Because the sigmoid sinus and jugular foramen are situated in the lateral part of the foramen magnum, lesions of foramen magnum must be approached from either the anterior or posterior side. The transoral approach, which is an approach from the anterior side, is rarely utilized. In contrast, the posterior approaches are often utilized and are divided into three groups: posterior midline, posterior paramedian, and lateral foramen magnum approaches [1, 2, 4, 6, 13, 16, 19–21]. The posterior paramedian is further subdivided into the intradural, epidural, and combined approaches. In this chapter, we explain the posterior paramedian intradural and epidural approaches for lesions in the anterior or anterolateral foramen magnum. In addition, we explain the surgical anatomy relevant to these approaches, including the bony structures, surrounding nuchal muscles, the VA as it penetrates the dura mater, and venous and neural structures near the foramen magnum.

The conditions for which these approaches are used include meningiomas in the anterior or lateral foramen magnum and chordomas originating from the lower clivus. We present the following two illustrative cases: a case of anterolateral foramen magnum meningioma operated through the intradural approach below the VA and a case of craniocervical junction chordoma operated through the C2 ganglion-sectioning epidural paramedian approach. The third case of anterior foramen magnum meningioma operated through the transcondylar fossa approach, one of the lateral foramen magnum approaches, is also presented to compare the two lateral approaches and their indications based on the VA.

16.2 Basic Structure of the Posterior Part of the Foramen Magnum

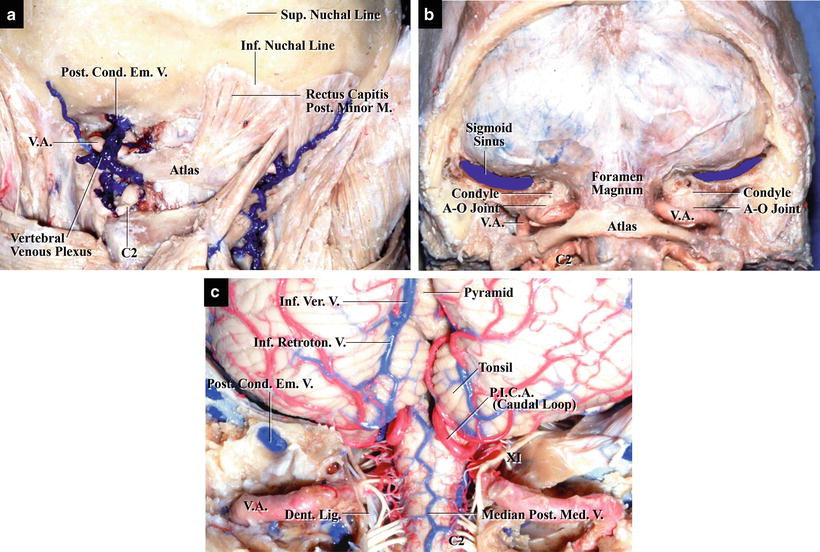

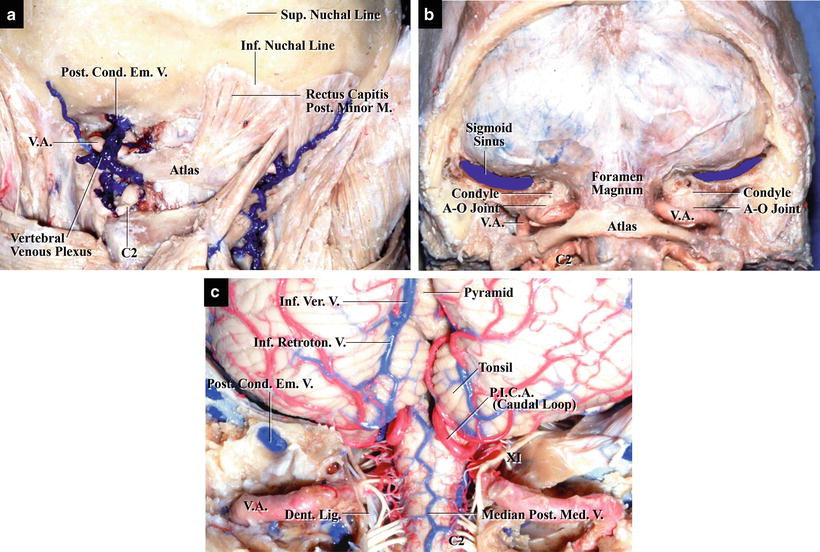

The foramen magnum lies in the occipital bone. Anterolateral to it, the occipital condyles articulate with the lateral masses of the atlas (C1) to form the atlanto-occipital joint [4, 15, 22, 25]. The VA runs around the atlanto-occipital joint from the extracranial to the intracranial side (Figs. 16.1 and 16.2). The extracranial VA, which courses in a groove on the posterior arch of the atlas (the sulcus arteriae vertebralis), sometimes protrudes from the posterior margin of the arch. The artery is surrounded by the vertebral venous plexus [4, 24]. This venous plexus communicates with the jugular bulb through the posterior condylar emissary vein, which runs in the posterior condylar canal (Fig. 16.1a, c) [10, 12, 15, 22]. These bony and vascular structures are covered by a large number of nuchal muscles.

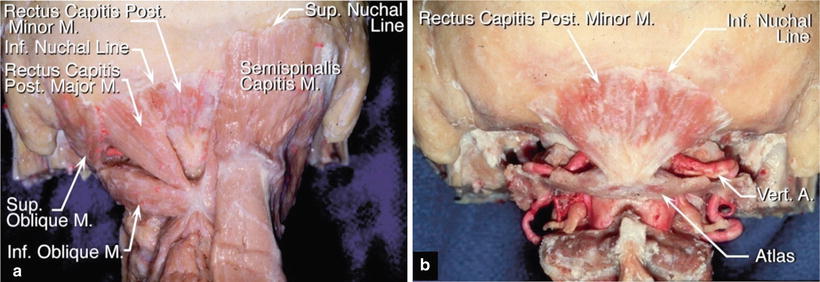

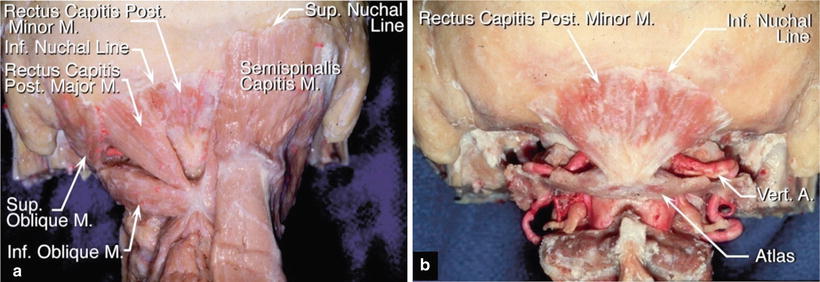

Fig. 16.1

The craniocervical junction, posterior view. (a) Nuchal muscles and extracranial veins. (b) Structures after craniotomy. (c) Structures after dural opening

Fig. 16.2

Illustrations of the anatomy of the foramen magnum, posterior view (from De Oliveira E et al. [4] with permission). (a) Posterior view with the cerebellum, spinal cord, and right cerebellar tonsil removed. (b) Posterior view with the cerebellum removed

16.3 Bony Structures of the Foramen Magnum

The occipital bone comprises three parts: basilar, lateral, and squama (Fig. 16.3a). The lower edges of each part form the foramen magnum. Usually, the foramen magnum is ovoid and narrow anteriorly. On the external surface of the occipital squama, the following bony markings are present: the external occipital protuberance and six bilateral curved ridges, i.e., the highest, superior, and inferior nuchal lines (Fig. 16.3b) [4]. The superior nuchal line arches laterally from the inferior margin of the external occipital protuberance, whereas the inferior nuchal line arches parallel to and below the superior nuchal line. The nuchal and suboccipital muscles are attached to the superior and inferior nuchal lines. When the suboccipital muscles are incised from the inferior nuchal line, they can be easily separated from the skull [15, 19]. The jugular foramen is formed by the lateral part of the occipital bone and the petrous temporal bone. Surgeons must have a detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the occipital condyle and the jugular tubercle because the condyle forms the atlanto-occipital joint, which forms an obstacle to surgical approaches from the posterolateral side (Fig. 16.3c) [2, 9, 13, 19–21]. Moreover, in some cases, it is necessary to remove parts of the occipital condyle and jugular tubercle while preserving the joint stability [2, 20]. The condyle is usually located anterior to the lateralmost point of the foramen magnum, but its position varies among individuals (Fig. 16.3a) [4]. The more posterior its location, the more difficult the approach becomes.

Fig. 16.3

The occipital bone and foramen magnum (from Matsushima T et al. [21] with permission). (a) Inferior view. The ovoid foramen magnum is formed by the basal (Bas.), lateral (Lat.), and squamous parts of the occipital bone. The occipital condyles, which articulate with the atlas, protrude from the external surface of the lateral parts. (b) Posterior view. The external occipital protuberance is situated in the central part of the external surface. The highest and the superior nuchal lines radiate laterally from the protuberance. The vertical ridge—the external occipital crest—descends from the protuberance. The inferior nuchal lines run laterally on both sides. (c) Left posterolateral view. The paired atlanto-occipital joints and the grooves for the vertebral artery are visible. The concave behind the occipital condyle is the condylar fossa. (d) Left posteroinferior view. The left condylar fossa is located posterior to the occipital condyle. The posterior condylar canal is evident at the bottom of the fossa

The hypoglossal and posterior condylar canals are situated at the base of the condyle. These canals contain veins, lie at almost the same level, and sometimes communicate with each other [10]. The hypoglossal canal, also called the anterior condylar canal, connects the foramen magnum and jugular foramen. The posterior condylar canal, in which the posterior condylar emissary vein communicates between the jugular bulb and vertebral venous plexus, opens in the bottom of the condylar fossa just behind the condyle (Fig. 16.3d) [10, 19, 21] (regarding the posterior condylar canal and posterior condylar emissary vein, refer to Chap. 17: “Surgical Anatomy of and Approaches through the Lateral Foramen Magnum: the Transcondylar Fossa and Transcondylar Approaches”).

The atlas comprises four parts: the anterior arch, posterior arch, and two lateral masses. The posterior arch of the atlas is equivalent to the lamina of other cervical vertebrae. The VA exits the transverse foramen situated between the lateral mass and transverse process and runs in a groove on the superior surface of the posterior arch (Fig. 16.3c). The superior and inferior articular facets lie on the superior and inferior surfaces, respectively, of each lateral mass. The superior articular facet articulates with occipital condyle to form the atlanto-occipital joint.

16.4 Nuchal and Suboccipital Muscles

When making the skin incision during suboccipital craniotomy, a major complication to avoid is injuring the extracranial portion of the VA. We will describe the anatomy of the nuchal and suboccipital muscles and the methods used to perform a safe skin incision. The nuchal and suboccipital muscles covering the occipital squama can be divided into three layers [4, 22, 25]. The first layer comprises the nuchal trapezius muscle and suboccipital sternocleidomastoid muscle. These muscles are attached to the highest and superior nuchal lines (Fig. 16.4a). The muscles of the second layer are attached to the region between the superior and inferior nuchal lines. The rectus capitis posterior major and minor, i.e., the muscles of the third layer, are attached to the inferior nuchal line (Fig. 16.4a, b). Only with an appreciation of the three-layered structure of the muscles and their attachment to the occipital squama can the skin incision be performed safely. We prefer a horseshoe-shaped skin incision because it can be made safely and quickly.

Fig. 16.4

The nuchal muscles (from Matsushima T et al. [21] with permission). (a) The second layer of nuchal muscles on the right side and the third layer on the left side. The semispinalis capitis muscle, one of the second-layer muscles, is visible on the right side. On the left side, the semispinalis and longissimus capitis muscles have been removed to show the rectus capitis posterior minor and major muscles. They are attached to the inferior nuchal line. (b) The rectus capitis posterior minor muscle: All muscles except rectus capitis posterior minor have been removed. The vertebral artery is covered by the rectus capitis posterior muscles

Extracranial VA, surrounded by the venous plexus, is present under the muscles of the third layer. When these muscles are separated from the inferior nuchal line with a raspatory, a skin flap can be reflected without injuring the VA. This also decreases the risk of damaging the vertebral venous plexus. The muscles of the third layer arise from the spinous process of the axis toward the inferior nuchal line, spreading in a fan-shape (Fig. 16.4a, b).

The suboccipital triangle is a region where extracranial VA can be easily injured because of the absence of muscles of the third layer. The triangle is bordered by the superior oblique, inferior oblique, and rectus capitis posterior major muscles. Injury of extracranial VA is not a big problem when we perform the muscle dissection considering their attachment to the inferior nuchal line. In cases requiring a horseshoe-shaped skin incision, it is necessary to exfoliate the muscles from the midline to the lateral side along the posterior arch of the atlas. As the VA runs in a groove on the posterior arch of the atlas and sometimes protrudes from the arch, care must be taken to avoid injuring the VA.

16.5 Vascular Structures Around the Foramen Magnum, Focusing on the Anatomy of the VA as It Penetrates the Dura Mater

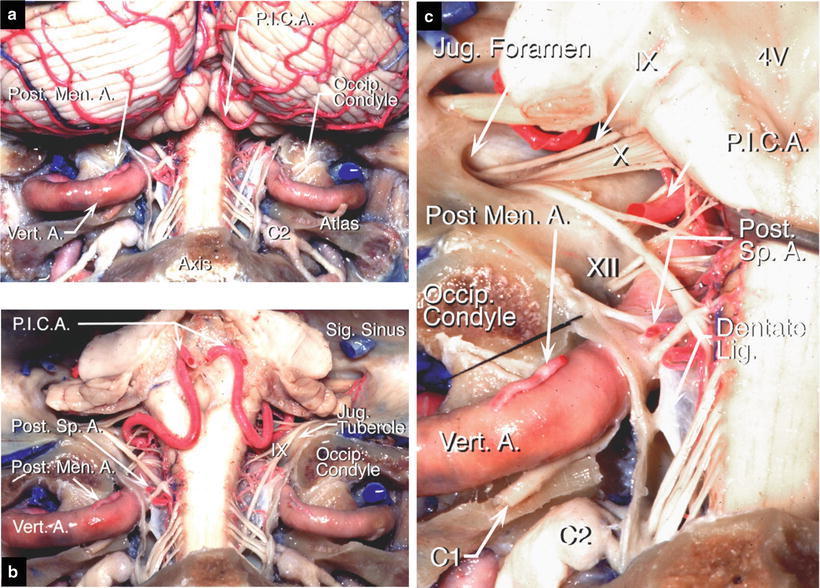

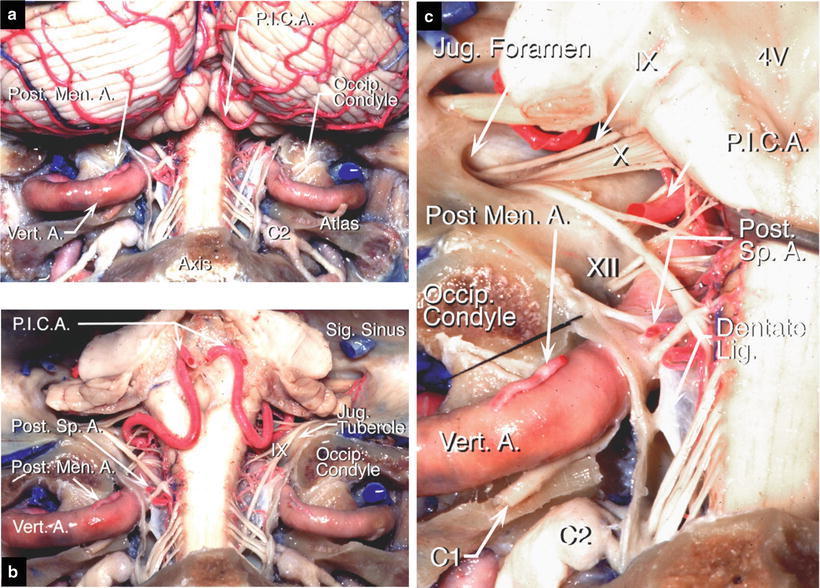

The VA is the only large artery around the foramen magnum. After passing through the transverse foramen, the VA courses in a groove on the atlas and runs around the atlanto-occipital joint to penetrate the dura mater from the extracranial to the intracranial side. The VA is surrounded by the vertebral venous plexus. The extracranial, horizontal portion of the VA running in the groove is situated inferior to the atlanto-occipital joint (Fig. 16.5a, b). After entering intracranially, the VA ascends between the medulla oblongata and jugular tubercle and condyle and unites with the contralateral VA to form the basilar artery (BA; Figs. 16.2b and 16.5c). During its course, the VA gives rise to four main branches: posterior meningeal artery, posterior spinal artery, posterior inferior cerebellar artery, and anterior spinal artery [4]. The area where the VA penetrates the dura mater in the foramen magnum is important in foramen magnum surgeries (Fig. 16.5c). For example, in cases of foramen magnum meningioma, we often have to dissect tumors from the dura mater and the VA at this site. The dentate ligament, the first and second spinal nerves, cranial nerve (CN) XI (the accessory nerve), and the posterior spinal artery are present at this site in addition to the VA.

Fig. 16.5

Arteries around the foramen magnum, posterior view (from Matsushima et al. [21] with permission). (a) The cerebellum and upper cervical spinal cord with the dura opened. The extracranial vertebral arteries (VAs) run around the atlanto-occipital joint, where they pass into the groove of the atlas. Then, the arteries penetrate the dura mater at the level of the foramen magnum. (b) The VA and the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA). The cerebellum has been removed. The lateral and posterior medullary segments of PICAs are visible. They form caudal loops. The upper end of the dentate ligament passes posterior to the VA before attaching to the dura at the level of the foramen magnum. The accessory nerves arise from the dorsolateral surface of the spinal cord and medulla and ascend toward the jugular foramina. (c) The region around the left VA as it penetrates the dura mater. The posterior meningeal artery arises from the VA before it enters the dura and the posterior spinal artery arises from the VA just after it enters the dura. The C1 nerve root is adherent to the lower margin of the VA

The dentate ligament, a white fibrous sheet of the pia–arachnoid membrane, is attached to the spinal cord medially and dura mater laterally. It is situated between the dorsal and ventral (anterior) roots of the spinal nerves. The most rostral process of the dentate ligament is attached to the dura mater at the level of the foramen magnum, and the second most rostral process is attached to the dura mater just inferomedial to the initial segment of intracranial VA. The initial segment of intracranial VA is covered with and fixed by the dentate ligament. CN XI and the dorsal root of the C2 spinal nerve course dorsal to the dentate ligament. The ventral root of the C1 spinal nerve runs anteroinferior to the VA. It can be seen when the intracranial portion of the VA is elevated. The posterior spinal artery also arises from the extra- and intracranial transitional portion of the VA where it penetrates the dura mater. Because the posterior spinal artery supplies the lateral aspects of the medulla oblongata and cervical spinal cord, care must be taken not to injure it.

The venous system around the foramen magnum includes the following: the marginal sinus in the dura mater, the vertebral venous plexus surrounding extracranial VA, the posterior condylar emissary vein in the posterior condylar canal, and the venous plexus in the hypoglossal canal (Fig. 16.6). They communicate with the jugular bulb in the jugular foramen [4, 10, 21, 22, 24]: the marginal sinus communicates via the venous plexus in the hypoglossal canal, and the vertebral venous plexus communicates via the posterior condylar emissary vein. When using the posterior or posterolateral approaches to foramen magnum lesions, the vertebral venous plexus is often encountered (Fig. 16.6b, c). If the vertebral venous plexus is injured, achieving hemostasis of the venous plexus is difficult and takes time in some cases. The posterior condylar emissary vein and posterior condylar canal are useful intraoperative anatomical landmarks for removing the condylar fossa through the lateral foramen magnum approaches [12, 13, 15, 19, 21] (regarding the venous system in the lateral foramen magnum, refer to Chap. 17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree