Chapter 1 Surgical Anatomy and Physiology of the Nose

Pearls

• Soft tissues of the nose are thick cephalically and caudally and become thinner in the center. It is for this reason that the nose frame that is totally straight on the profile will most likely not induce an optimal dorsal outline.

• There are 4 distinct layers that occupy the area between the skin and underlying osteocartilaginous frame, including the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), fibromuscular layer, deep fatty layer, and periosteum/perichondrium.

• Damage to the pars alaris muscle may result in collapse of the external nasal valve.

• Release of the depressor septi nasi muscle not only eliminates the depressor effect on the nasal tip, it may also cause a slight ptosis of the upper lip which may or may not be beneficial to the patient depending on the amount of incisor show.

• African-American noses often have short nasal bones. This becomes significant in maintaining the width of the nose after nasal bone osteotomy.

• Osteotomy and medial repositioning of the long nasal bones will have a deleterious effect on the airway since it will transpose the upper lateral cartilage medially as well.

• The confluence of cartilaginous nasal septum, ethmoid bone, and nasal bone is called the keystone area.

• Overall, the two paired middle and medial crura structures constitute the caudal leg of the basal nose tripod, the other two legs of which comprise the lateral crura. Understanding the tripod mechanism in reduction of tip projection and its rotation is absolutely crucial to the delivery of tip projection objectives.

• The lower lateral cartilage is commonly short and weak in non-Caucasian noses.

• The angle between the caudal border of the upper lateral cartilage and the septum, usually 10–15°, composes the internal valve along with the border of the inferior turbinate.

• Continuous interweaving of the perichondrium and the periosteum at the junction of the vomer bone and the cartilaginous septum anteriorly makes dissection in this part very difficult. It is easier to dissect the mucoperiosteum and mucoperiostium posteriorly and extend it anteriorly during the septoplasty.

• The highly vascular area that receives arterial circulation from the superficial terminal branches of the anterior ethmoid, the sphenopalatine, and the superior labial arteries is called Kesselbach’s plexus, which is a common source of anterior nasal bleed because of the robust blood flow.

• The optimal turbulence of the nose will occur with a nasolabial angle of 90–115°.

Rhinoplasty Terminology

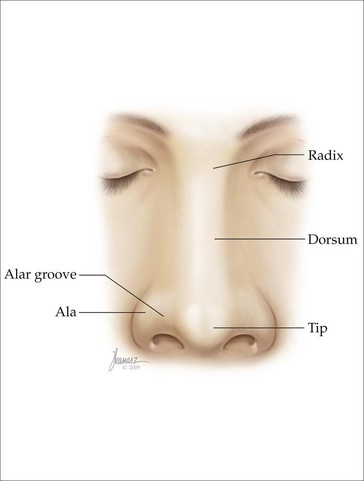

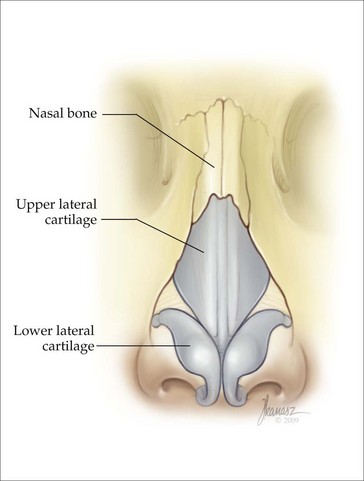

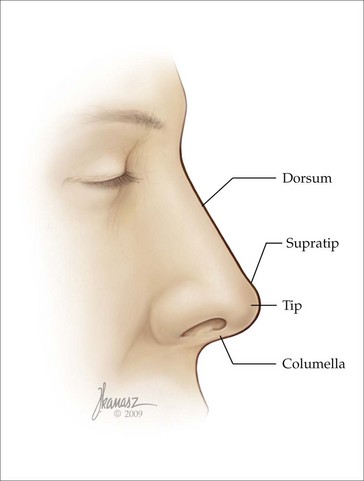

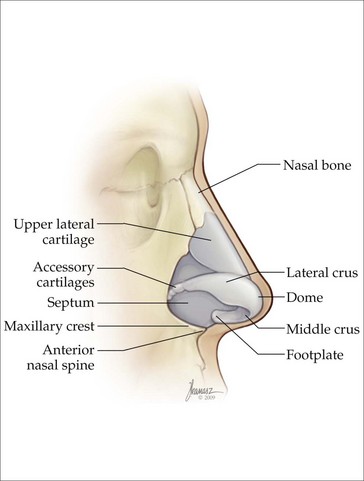

Even though the nose occupies only a small area of the face, the terminology used to define the different parts of the nose is vast and confusing. In order to improve understanding of this terminology, we will try to list and explain these terms, as described in different textbooks,1,2,26 including all variations that have been used to describe a specific site (Figures 1.1–1.4).

• Accessory cartilages – small cartilages located between the lateral ends of the lateral crura and the pyriform aperture

• Ala – the lateral nostril wall extending from the tip to the upper lip and cheek

• Alar groove – the oblique skin depression between the tip and the ala

• Anatomic dome – the most anterior projected portion of the lower lateral cartilages between the medial and lateral crus

• Anterior septal angle – the junction of the anterior and caudal cartilaginous septum

• Columella – the column between the nostrils at the base of the nose

• Columellar-lobular angle – the angle between the infratip lobule and the columella

• Dorsum – the anterior surface of the nose between the tip and the radix (Figure 1.5)

• External nasal valve – the external opening of the nostril

• Hemitransfixion incision – an incision through only one side of the membranous septum

• Infratip lobule – the portion of the tip between the tip defining points and the columellar-lobular junction

• Intercartilaginous incision – an internal incision placed at the junction of the upper lateral cartilage with the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage

• Internal nasal valve – the area located between the caudal edge of the upper lateral cartilage and the nasal septum

• Keystone area – the junction of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid with the septal cartilage at the dorsum of the nose

• Limen vestibuli – the junction of the caudal edge of the upper lateral cartilage with the cephalic margin of the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage

• Lower lateral cartilages – the paired caudal nasal cartilages consisting of the medial, middle, and lateral crura

• Marginal or infracartilaginous incision – an incision placed along the caudal border of the medial and lateral crura

• Footplate of the medial crura – the posterior segment of the medial crura that extends laterally

• Nasal lobule – the caudal part of the nose bounded posteriorly by the anterior nostril edge, superiorly by the supratip area, and laterally by the alar grooves

• Nasal pyramid – part of the nasal frame made up of the bilateral nasal bone and frontal process of the maxilla

• Nasion – the depression at the junction of the nose with the forehead

• Nasolabial angle – the angle formed by a line drawn through the most anterior to the most posterior point of the nostril intersecting the vertical facial plane on the lateral view (desired angle is 94–97° in males and 97-100° in females)36

• Nostril sill – the horizontal ridge between the columellar base and the alar base

• Pyriform aperture – the pear-shaped external bony opening of the nasal cavity

• Radix – the junction between the frontal bone and the nasal bones

• Rhinion – the point located at the osseocartilaginous junction over the dorsum of the nose

• Rim incision – an incision placed just within the vestibular edge of the rim of the naris

• Scroll area – the interlocking, curled junction between the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage and the upper lateral cartilage

• Sesamoid cartilages – small cartilages found in the lateral space between the upper and lower lateral cartilages

• Soft triangle – the thin skin fold between the anterior portion of the nostril and the caudal border of the dome between the medial and lateral crura

• Subnasale – the junction of the columella with the lip

• Supra-alar crease – the groove immediately cephalad to the alar crease

• Supratip area – the area just cephalad to the nasal tip at the caudal portion of the nasal dorsum

• Tip – The most anterior point of the lobule

• Tip defining points (TDP) – the most projecting area on each side of the tip that produces an external light reflection

• Tip projection – the distance from the most projected portion of the tip to the most posterior point of the nasal–cheek junction

• Tip rotation – movement of the tip cephalad or caudad pivoted at the alar base on the profile view

• Transfixion incision – an incision in the membranous septum between the caudal border of the septal cartilage and the columella

• Upper lateral cartilages – the paired cephalad nasal cartilages spanning laterally from the anterior septum and composing the lateral walls of the middle third of the nose

• Weak triangle (converse) – the area immediately cephalad to the paired domes

Skin

One of the key determining factors in the outcome of the rhinoplasty is the quality of the nasal skin. The skin color, consistency, thickness, and porous nature vary from patient to patient, on different parts of the same patient’s nose and at different stages of life. The skin is thicker at the radix than the central portion. However, in some patients the supratip area is even thicker than the radix and contains more sebaceous glands. Lessard & Daniel have determined that the average skin thickness is greatest at the radix (measuring 1.25 mm) and the least at the rhinion (approaching 0.6 mm) (Figure 1.5).1

The alar base area contains more fibrous bands, which is the reason for its rigidity. The vestibule is the cavity just inside the external nares bounded by the membranous septum and the columella medially and the side wall of the ala laterally, the latter being covered with hair (vibrissae).2

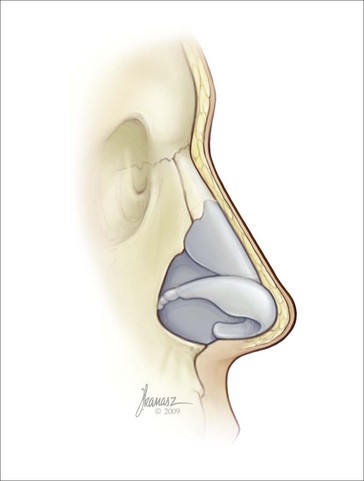

Soft Tissue Layers Beneath the Skin

There are four distinct layers that occupy the area between the skin and the underlying osseocartilaginous frame: the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) as originally described by Tessier,3 fibromuscular layer, deep fatty layer, and periosteum/perichondrium.2 Immediately under the skin, there is a superficial fatty panniculus, which is largely occupied by adipose tissue containing some vertical fibers and septi running from the skin to the underlying SMAS.2 This layer again is significantly thicker in the radix area, and becomes extremely thin in the mid-vault region and thickens in the supratip area. The SMAS of the nose is the continuation of the sheath that extends across the entire upper half of the face.

Under the SMAS there is a thin fibrofatty layer that divides to encase the superficial and deep muscles of the nose.3,4 Wherever there is no muscle, these two layers join, creating a single layer.

The fourth soft tissue layer is the periosteum over the nasal bones and the perichondrium over the cartilaginous frame. There are several fibrous connections joining the cartilages to each other, some extending from the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages to the upper lateral cartilages and connecting the accessory cartilages to each other. There is a fibrous band extending from one lateral crus to the opposite one in the supratip area which is called the Pitanguy ligament.5 Additionally, there are dense fibrous bands between the caudal septum and the medial crura. There are also fibrous bands between the medial crura.

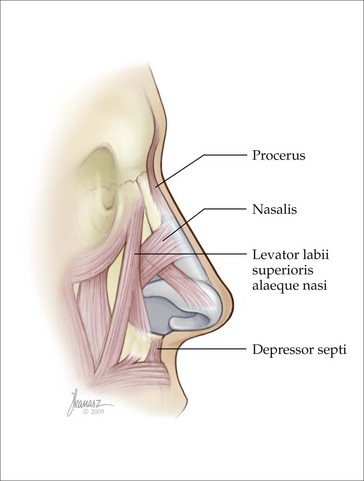

Nasal Muscles

The description of the muscles of the nose and explanation of their functions is one of the most confusing aspects of the body of knowledge germane to rhinoplasty. In fact, many of the articles written about the nasal musculature assign different names and functions to the same muscles of the nose. All these muscles are innervated by the VIIth cranial nerve. The following is a description of the nasal muscles and an outline of their function6 (Figures 1.6 and 1.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree