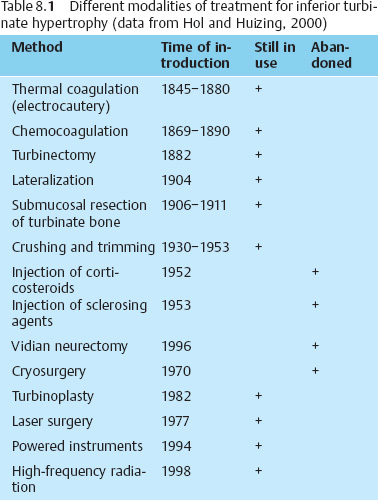

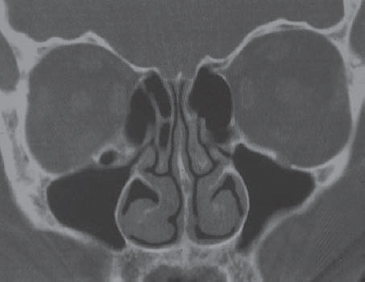

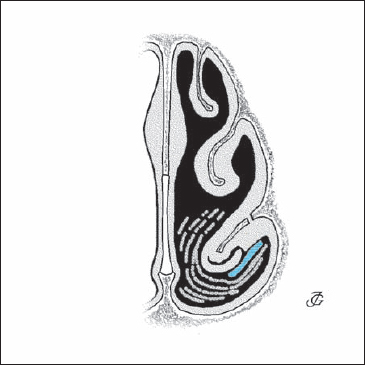

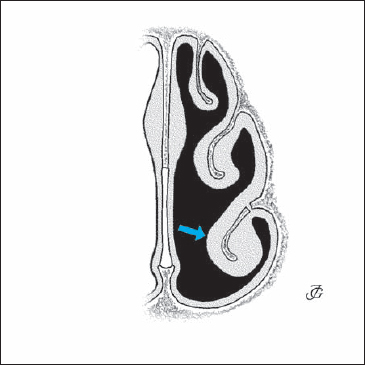

8 Surgery of the Nasal Cavity Pathology of the turbinates is one of the most frequent causes of nasal complaints. Obstructed breathing, hypersecretion, sneezing, itching, hyposmia, and pressure sensations are the most common symptoms. Remarkably, most textbooks and courses on nasal surgery pay little or no attention to turbinate pathology and its treatment. Instead they concentrate on the septum, pyramid, and lobule. Nonetheless, disorders of the turbinates are extremely common in daily rhinological practice. Therapy of turbinate disorders should take account of the character and the cause of the pathology. Remarkably, however, specific types of turbinate pathology are rarely distinguished. Most textbooks and articles refer to “hyperplastic,” “hypertrophic,” “engorged,” or “congested” turbinates. In an attempt to provide grounds for choice of treatment, this chapter differentiates between various types of turbinate pathology. The choice of a therapy for turbinate disorders has been a matter of dispute for over a century. What all authors do agree on is that conservative treatment—with topical steroids, antihistamines, systemic antibiotics, depending on the cause of the pathology—should be first choice. Medications are permanently effective in a limited number of cases, however. Surgical treatment—usually some kind of turbinate reduction—is then considered. When choosing a method of turbinate reduction, we must keep in mind that turbinates are very important functional structures because they enable the nose to perform its tasks. They regulate the course of the airstream; they humidify, warm, and cleanse the inspired air; and they are the main organs of defense for the upper respiratory tract. Preservation of these functions is therefore obligatory. As previously noted, we need a workable classification of turbinate pathology. In our experience, the following types may be distinguished: Compensatory hyperplasia is a very well-known pathological entity. In patients with a septal deviation, it develops on the wide side of the nose (see Fig. 2.105a). It is a physiological reaction that serves to diminish the size and normalize the configuration of the breathing space in the pathologically wide nasal half. Therefore, it is questionable whether septal surgery has to be combined with turbinate reduction in these cases. There are compelling reasons to wait and see if a physiological correction takes place. In a prospective study, Grymer et al. (1993) found that septal surgery combined with turbinate surgery did not yield a better functional outcome than septoplasty alone. Protrusion is identified less frequently. The experienced rhinologist will recognize it at rhinoscopy, but it may show up more clearly on a CT scan. The angle between the turbinate bone and the lateral nasal wall is larger than average, sometimes even up to 90° (Fig. 8.1). See also Figure 2.105b. As a consequence, the turbinate protrudes further into the nasal cavity than usual. Lateralization by fracturing the turbinate bone in combination with a limited submucosal resection of the anteroinferior part of the bone is usually an effective treatment. Hyperplasia of the turbinate head is a very common type of pathology. It is observed in most patients suffering from allergic and hyper-reactive rhinitis. The congested head of the turbinate protrudes in a medial and anterior direction and obstructs the valve area. It is important to distinguish this condition from hypertrophy of the whole turbinate and of the tail. Topical or systemic use of corticosteroids and/or antihistamines is the preferred therapy. If ineffective, an anterior turbinoplasty is usually the best solution as this type of surgery reduces turbinate volume at a critical area without loss of function. Hyperplasia of the whole turbinate is an even more common symptom of allergic and hyper-reactive rhinitis (see Fig. 2.106b). Our therapeutic approach is the same: first treat with medications; if ineffective, resort to surgical reduction of the whole turbinate by intraturbinal resection of bone and parenchyma or by crushing and trimming (see text following). Hyperplasia of the turbinate tail is frequently seen in patients with chronic sinusitis and postnasal discharge. The mucosa and submucosa have become hyperplastic due to continuous infection and they degenerate irreversibly with the formation of polypoid, papillomatous, or fibrous new growth (see Fig. 2.106c). Resection of the pathology with some trimming of the turbinate is usually the best remedy. As previously noted, we will first consider conservative treatment, as we would in the majority of cases of turbinate pathology. The effect of a corticosteroid spray and/or systemic or topical antihistamines should be tested in allergic or hyper-reactive patients for at least 3 months. Where infection plays a role, a course of antibiotics (sometimes in combination with antihistamines or corticosteroids) should be given first. In patients who do not respond within 3–6 months, surgery must be considered. Over the past 130 years, at least 13 different methods have been used to treat hypertrophy of the inferior turbinate. These are, in chronological order: thermal coagulation (electrocautery), chemocoagulation (chemocautery), (partial) turbinectomy, lateralization, submucosal resection of the turbinate bone, crushing and/or trimming, injection of corticosteroids, injection of sclerosing agents, vidian neurectomy, cryosurgery, turbinoplasty, laser surgery, and reduction using powered instruments. While several of these procedures have been abandoned, quite a few are still in use. An overview is given in Table 8.1. In our opinion, several of the present techniques are to be condemned, as they are unnecessarily destructive to nasal function. Procedures to reduce a turbinate should be judged by two basic criteria. The first is the efficacy of the technique in alleviating breathing obstruction, hypersecretion, recurrent infection, sneezing, and headaches. The second is an assessment of the procedure’s side effects, both in the short and the long term. It would be a mistake to focus solely on the degree of widening of the nasal passages in terms of endoscopic findings, rhinomanometry, and acoustic rhinometry. A wider nasal cavity does not necessarily mean the nose functions better. The aim of turbinate surgery must be to diminish complaints while preserving function. Fig. 8.1 Protrusion of the inferior turbinate. There is a wide angle between the turbinate bone and the lateral nasal wall. Thermal coagulation or electrocautery was initially introduced in the period 1845–1860. The method gradually gained in popularity, eventually coming into widespread use when cocaine became available as a topical anesthetic in the 1880s. Even today, electrocautery is still popular. Surface electrocautery was introduced first. In the 1920s, high-frequency surface diathermy was described. Surface electrocautery usually requires cutting two parallel furrows into the turbinate. As a result of coagulation of the tissues, the turbinate is diminished in size. During the healing process, further reduction takes place by retraction of the scar tissue. However, irreversible damage has been done to the mucosa, with its cilia, glands, and defense systems. The epithelium becomes metaplastic, and mucociliary transport is abolished. Crusting may occur, and patients often complain of nasal dryness and irritation. Synechiae are another common side effect. In terms of function, surface electrocautery is obviously a destructive procedure. It does not meet the requirement of diminishing complaints while preserving function. Modern variations, such as submucosal bipolar diathermia and the recently propagated high-frequency diathermy, may cause less superficial damage. The aim of turbinate surgery must be to diminish complaints while preserving function. Chemocoagulation or chemocautery with chromic acid or trichloric acid was introduced as an alternative to electrocautery in the last decades of the 19th century. In our opinion, chemocautery of the turbinate mucosa is the worst treatment imaginable. It does not reduce the turbinate volume but causes damage to all functional elements of the mucosa. Nevertheless, the method is still used. Turbinectomy also dates from the last decades of the 19th century. Resection of the inferior turbinate became one of the most frequently practiced rhinological surgical procedures in the first quarter of the 20th century. Special instruments were designed, such as Struycken’s scissors. Soon after its introduction, however, reports about postoperative atrophic rhinitis and “secondary” ozena appeared. This led many surgeons to use more conservative techniques such as lateralization, partial resection, and submucous resection of turbinate bone. In the 1970s and 1980s, turbinectomy was again recommended by several authors. Many of them disputed claims that it might lead to atrophic rhinitis or a “wide nasal cavity syndrome.” Noting the numerous complications, others disagreed. Stenquist and Kern coined the term “empty nose syndrome.” A review of the literature on this controversial issue was recently presented by Hol and Huizing (2000). In our opinion, turbinectomy is a nasal crime. We feel that there is no reason (apart from malignancies) to resect more than one-third to one-half of the inferior turbinate. Lateralization by outfracturing the turbinate was introduced as early as 1904 by Killian, among others. This conservative function-preserving method is still widely used, particularly as a flanking procedure along with septoplasty. Since its effect is rather limited, several variations have been suggested, such as lateral fixation (“lateropexia”) or partial dislocation of the turbinate into the maxillary sinus after resection of part of the lateral nasal wall. Understandably, these methods did not have much of a following. Submucosal resection of the turbinate bone was presented by several authors in the years 1906–1911, as an alternative to the more aggressive techniques previously discussed. Despite its attractivity, this procedure gained only limited popularity. In 1951, Howard House revived the method. The anterior part of the bony lamella, together with some of the parenchyma, is resected through an incision at the head of the turbinate (Freer 1911). Mabry (1982, 1984) refined the technique and introduced the term “turbinoplasty.” As the mucosa and submucosa are preserved, the method meets our requirement of “volume reduction with preservation of function.” In the recent comparative study by Passali et al.(1999), this technique came out as the best method. Crushing and/or trimming was recommended as a less destructive alternative to turbinectomy in the early 1930s. The turbinate is first crushed in an effort to damage and thus reduce the amount of the parenchyma and, at the same time, to leave the mucosal surface intact. It is then trimmed to size. In trimming or partial resection, various techniques have been employed: horizontal or diagonal resection of the inferior margin; resection of the posterior part; and resection of the anterior part. From the viewpoint of preserving function, all of the above variations appear to be acceptable, provided they are performed in a conservative way. Personally, we prefer the crushing and trimming technique in cases where submucosal turbinate reduction is not appropriate. Although this method is certainly not ideal, it seems to represent the best compromise between desired results and side effects. Total turbinectomy is a “nasal crime”. Injection of a long-acting corticosteroid solution was introduced in 1952. Many authors reported beneficial results. The effect lasted only a few months, however. Later, the method was discouraged after reports of acute homolateral blindness appeared. Injection of sclerosing agents was suggested for the first time in 1953. The method did not come into general use because of its unpredictable results and complications. Vidian neurectomy was introduced by Golding Wood in 1961 as a completely different approach to the problem of turbinate hypertrophy and hypersecretion. Parasympathetic innervation was severed by cutting the nerve fibers in the Vidian canal through a transantral approach or endonasal coagulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion. Usually, some decrease of hypersecretion was obtained. The effect on blockage was poor. Since the effects appeared to be temporary, the method was abandoned in the 1970s. Cryosurgery was the next step in the long history of treatment of inferior turbinate hypertrophy. It was widely used in the 1970s, but its popularity soon declined. The amount of reduction appeared to be rather unpredictable. Total turbinectectomy must be considered a nasal crime. “As soon as we have got a new instrument, you will see that it is immediately tried out on the turbinates.” (Wolfgang Pirsig). Powered instruments like “shavers” have recently come into use in turbinate surgery. These instruments are used on the turbinate surface as well as intraturbinally, often in combination with an endoscope. Use of a powered instrument appears to be a matter of personal preference. The results depend less on the instrument that is used than on the surgical concept. High-frequency diathermy is the most recent technique for reducing turbinate hypertrophy. Again it makes a difference whether it is used superficially or endoturbinal. See the discussion above. In conclusion: When accepting that the aim of turbinate surgery must be to diminish complaints while preserving function, we have to come to the conclusion that only three of the methods discussed above are acceptable: The choice of technique in an individual case will depend on the type of pathology. All procedures may be carried out under general or local anesthesia (for techniques see Chapter 3, p. 118ff). If local anesthesia has been chosen, care is taken to thoroughly block the branches of the pterygopalatine and nasopalatine nerves as they innervate the posterior part of the inferior turbinate (see Fig. 1.57). In reducing a turbinate, it depends not so much on the instrument that is used. Rather, it is the surgical concept that counts. The most function-preserving technique of reducing a hypertrophic inferior turbinate is submucosal turbinoplasty. The method is based on the principle of submucosal turbinate bone resection. It was developed into an elegant plastic procedure by Mabry, Lindsay Gray, Pirsig, and others. This technique is the method of choice for patients in whom the hypertrophy is restricted to the head or the anterior half of the turbinate. If the posterior part of the turbinate and/or its tail is involved, it may be better to use the crushing and trimming technique. If the hyperplasia is limited to the head of the turbinate, only an anterior turbinoplasty is carried out. Acoustic rhinometry before and after decongestion may provide definite proof of this diagnosis(see Figs. 2.122–2.123). Steps Lateralization (lateral displacement) of the inferior turbinate by outfracturing the turbinate bone is the most conservative method to address turbinate obstruction. It is mostly used in combination with another procedure as lateralization alone is rarely effective enough. It is often combined with septal surgery or one of the volume-reducing techniques described in the followong text. Steps Fig. 8.2b A medially based mucosal flap is dissected. Fig. 8.2c The anterior or the anteroinferior part of the turbinate bone is resected together with some of the parenchyma as required. Fig. 8.2d The mucosal flap is repositioned. Fig. 8.3 Lateralization of a protruding or hyperplastic inferior turbinate is performed using the flat, blunt end of a Cottle chisel. When the inferior turbinate is hypertrophic both anteriorly and posteriorly, crushing and trimming would be the best compromise between reduction and preservation of function. The whole turbinate is first compressed using a special forceps and then reduced by resecting a parallel or slightly diagonal strip from its inferior margin. The technique respects the functional capacity of the remaining part of the turbinate. Steps

Turbinate Surgery

General

General

Types of Turbinate Pathology

Function-Preserving Treatment

Inferior Turbinate

Inferior Turbinate

Pathology

Treatment

Conservative Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Methods

Criteria for Evaluating Methods of Reducing Turbinate Volume

Surgical Techniques

Surgical Techniques

A Critical Evaluation

1. Submucosal Turbinoplasty

2. Lateralization

3. (Crushing and) Trimming

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree