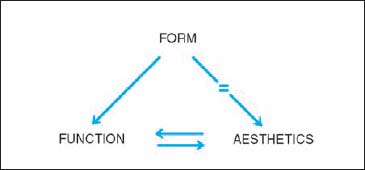

3 Surgery—General The primary objective of nasal surgery should be to restore nasal function. The nose evolved to facilitate smelling and breathing, to detect odors, to control the inspiratory and expiratory airstream, to humidify and warm inspired air, and to serve as the first line of defense of the respiratory tract. The primary task of the nasal surgeon is therefore to ensure proper nasal function. Nowadays, a large proportion of all nasal surgery is done in pursuit of the elusive goals of beauty and happiness. It is telling that most books on nasal surgery that have appeared over the past few decades are devoted to cosmetic rhinoplasty. No matter how legitimate the pursuit of beauty may be, the nasal surgeon should be aware of the limits of surgery. If a person’s nose is considered “normal” with respect to their ethnic origin, gender, and age, changing its features may run counter to medical ethics. Even in today’s Western civilization, the primary objective of nasal surgery must be to restore function. The goal of functional improvement must always be given priority over that of enhancing beauty. “There could be something insincere about changing a nose.” Arthur Miller “After the Fall” (1964) Fig. 3.1 Aesthetics and form are identical, while function is dependent on form. Function and aesthetics usually complement each other, however they may be in opposition. In this case, surgery for function should prevail over surgery for aesthetics. Interrelationship between form, function, and aesthetics in nasal surgery. Nasal surgery or rhinoplasty should be functional and reconstructive. In the words of Kern, we try to “recreate normality.” Function is restored by reconstructing normal anatomy. “In functional reconstructive nasal surgery we try to recreate normality.” Eugene B. Kern Septal deformities are corrected and septal defects are reconstituted; a deviating bony and cartilaginous pyramid is straightened; a distorted nasal valve is corrected; irreversible hypertrophy on a turbinate is reduced. All tissues are handled conservatively and preserved whenever possible. Resections should be limited. Tissue is only removed where necessary for repositioning and reconstruction. A special effort is made to preserve mucosal membrane, the functional organ of the nose. If the turbinates are to be reduced, the required reduction in volume is achieved by a method that ensures preservation of its function. To achieve our goals of reconstituting function and form, we apply the following three basic principles: Surgery of deformities of the external nasal pyramid commenced in the second half of the 19th century using external incisions (Dieffenbach, Berlin, 1845). The introduction of the endonasal approach to correct a dorsal hump and a bulbous prominent tip by John Orlando Roe of Rochester, New York (1887) was a great step forward. This method was further developed by others, in particular Jacques Joseph in Berlin in the first decade of the 20th century. In the 1920s, Réthi of Budapest introduced an approach to the nasal dorsum through an incision at the lobular base. Although his method did not have many followers, it was never completely forgotten (e.g. Šercer 1957, 1962). In the 1970s, when almost all nasal surgeons were satisfied with the endonasal route to the various nasal deformities, the external approach was reintroduced. Within a few years the “open approach” became very popular as it allows “open structure” surgery. The external approach through a midcolumellar incision proved to be a great step forward, particularly in correcting lobular pathology. Both the endonasal and the external approach have their advantages and disadvantages. Which method is used in an individual case depends on various factors: first, the type of pathology and the surgical goals and second, the surgeon’s personal preference and surgical experience There is no such thing as a “typical” or “standard” rhinoplasty. In general, we could say that what can be done endonasally should be done endonasally. One of the many reasons is that internal incisions are preferable to external incisions. External incisions are often said to become “almost invisible” when the tissues are handled delicately and sutured precisely. This may be true, but an invisible endonasal scar is preferable to an “almost invisible” external scar at the nasal base. A second reason is that, generally, the external approach is clearly more traumatic to the vulnerable lobular structures than the endonasal one. In spite of these drawbacks, the external approach is to be preferred in many patients as it provides a better access and overview to pathology of the lobule and the anterior septum. The best approach to the septum is the endonasal route using the caudal septal incision (CSI). This method combines the advantages of an endonasal incision with optimum access to all parts of the septum, in particular posteriorly. However, the external approach can also be applied very well to deformities of the anterior septum. This particularly applies to reconstruction of the anterior septum as was shown by Rettinger. A deviated pyramid can generally best be corrected by the endonasal approach. Combining a CSI with a bilateral intercartilaginous incision (IC) provides excellent access to most types of septal-pyramid pathology, such as the deviated nose, the hump nose, the saddle nose, and the prominent, narrow pyramid syndrome. There is no doubt, however, that in some cases the external approach can be applied as well. In modifying the lobule, particularly in patients with more pronounced lobular pathology, the external approach offers several advantages. The direct view allows a more atraumatic dissection and better adjustment and modification of the cartilages. The external approach is the method of choice in patients with pronounced lobular abnormalities and in most revision cases. In corrective nasal surgery, the sequence of the surgical steps is of great importance. There are no fixed rules, however. In our opinion there is no such thing as a “standard” or “typical” rhinoplasty as we find this described in some older textbooks. The way we deal with the problem depends on the pathology, the patient’s history, and the surgical goals. The sequence of steps depends first of all on the surgical approach: the endonasal or the external (or open) approach. The usual sequence of steps when using the endonasal approach is as follows: The usual sequence of steps when using the external approach is as follows: It is a matter of personal preference whether the lobular surgery is carried out before or after performing osteotomies and repositioning the bony pyramid. If a bloodless field has been achieved, the pyramid is usually corrected first. Then, the lobule is adjusted to the new situation. Both the patient and the doctor want the results of surgery to be excellent. However, operations are not always as successful as both parties would like them to be. This certainly applies to functional reconstructive and aesthetic nasal surgery. Some patients may be disappointed. In certain cases, this might lead to a conflict or even a complaint or lawsuit. Rhinological surgeons who are experienced in writing expertise reports in such cases have noted that the majority of patient–doctor conflicts are due to insufficient preoperative consultation, misunderstanding, and unrealistic expectations of the patient rather than to surgical failures. It is therefore of utmost importance to spend enough time ensuring that the patient will understand the benefits and risks of surgery in his or her case. Modifying the patient’s nose on a computer screen and suggesting or promising that the postoperative result will be the same can induce false expectations. Medicolegally it may be a case for sueing. An information leaflet may help the patient understand the various modalities of nasal surgery and the way the surgery and the preoperative and postoperative care is organized. In some countries like Germany, the surgeon is obliged to present such a leaflet to the patient. The patient should also understand that nasal surgery implies modifying living tissues, which means that the desired results can never be promised. The leaflet should also provide information about the most common complications. Over the past two decades, it has become customary to have the patient sign an informed consent form. In this form the patient declares that he or she has been informed about the type of surgery, the chances of success, and possible complications. Whether an informed consent form is used depends on the national legal situation. To a certain extent, this document violates the specific personal doctor–patient relationship which is so valuable and basic in the practice of medicine. In a sense it degrades this special relationship to a commercial one. On the other hand, it safeguards both parties and may prevent later uneasy discussions. In some countries, proposals to introduce the form have been turned down, as it was thought to cause too much anxiety in patients. The risks to be discussed or to be mentioned in an information leaflet and an informed consent form have always been a matter of discussion. In many countries, it is generally accepted that complications occurring more frequently than in 1% of cases must be mentioned. In our opinion, we should add that very serious complications with a lower incidence should also be discussed (e.g., meningitis or blindness). A surgical plan is usually made and discussed with the patient at the second office visit (see previous text). This plan may be further worked out together with the patient at the check-up examination (the day) before surgery. The sequence of the various surgical steps is finalized at the operating table after the local anesthesia has been administered and the nasal mucosa is decongested. The sequence of the surgical steps depends first of all on the pathology and the improvements that are to be achieved. Another important factor is the surgical approach to be used, the endonasal or the external approach. In cases with extensive pathology, such as a bony and cartilaginous saddle nose, surgery in two phases may be indicated. In a two-phase operation, the septum and pyramid are addressed in the first operation, while the lobular work and additional augmentation is performed at the second stage 9–12 months later. With the external approach, this sequence is slightly different. After exposing the lobular cartilages, cartilaginous dorsum, and caudal septal end, the septum is addressed first. The cartilaginous and bony pyramid are modified in the second step, followed by lobular surgery, augmentation, and fixation as required.

Concepts of Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery

Surgery For Function and Form

Surgery For Function and Form

Concepts

Concepts

Basic Principles

Basic Principles

Endonasal vs External Approach

Endonasal vs External Approach

Historical Development

Advantages and Disadvantages of Each Approach

Which Approach to Use when?

Septum

Bony and Cartilaginous Pyramid

Lobule

Sequence of the Surgical Steps

Sequence of the Surgical Steps

Endonasal Approach

External Approach

Preoperative and Postoperative Care

Preoperative Cares

Preoperative Cares

Discussing the Benefits and Risks of Surgery

Informing the Patient

Obtaining Informed Consent

Risks to be Discussed

Planning Surgery

Preparing for Surgery

Informing the Patient

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree