CHAPTER 14 Surgery for the Neuropathic Foot and Ankle

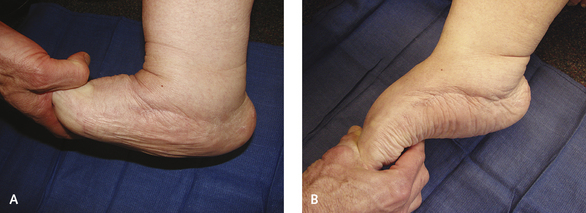

Once the process reaches the chronic phase, the midfoot typically is stable and is unlikely to deform further. However, bone prominence often is present on the plantar aspect of the midfoot, which may lead to ulceration or infection. In this context, “chronic” implies clinically stable, with an absence of swelling and inflammation (Figure 14-1). In these chronic arthropathies, the apex of the deformity is somewhere on the plantar foot. The “chronic” designation does not always equate with anatomic stability, however, because in a subgroup of midfoot arthropathies, the midfoot is quite unstable yet is not warm to touch. The deformity in such instances is very difficult to treat because of the very unstable rocker-bottom deformity of the midfoot (Figure 14-2).

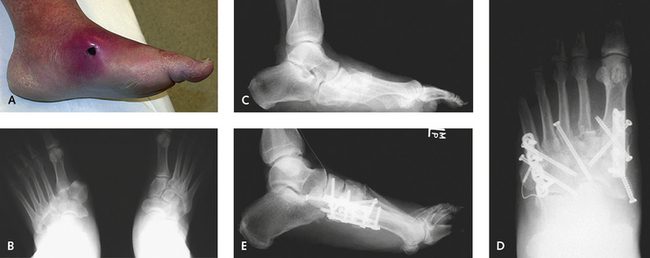

Patients can experience pain from the deformity, and although neuropathy may be thought of as being complete and not associated with any sensation, some patients experience deep, aching discomfort. Accordingly, it is appropriate to indicate surgical reconstruction with for use in such cases. Chronic deformity, recurrent ulceration, pain, and an unbraceable deformity are reasonable indications for reconstruction, but only if treatment-approach orthotics and prosthetics have failed to produce improvement or is unrealistic to begin with (Figure 14-3). There remains a “gray zone” in which the decision for performing reconstruction is more difficult if not controversial. The experienced clinician, however, gains a “feel” for the foot that helps guide decisions about the type of treatment needed. Patient factors including compliance, weight, extent of neuropathy, perfusion, skin condition, family support, opposite limb function, mobility of the ankle, and travel distance required for foot care all need to be considered in planning surgery for either the acute or the chronic stage of neuroarthropathy. The importance of these factors must not be underestimated. No matter how skillful the surgeon, the surgery will be useless if the patient lacks the means to comply with the restrictions on weight bearing and personal care requirements during rehabilitation.

CORRECTION OF NEUROPATHIC DEFORMITY OF THE MIDFOOT

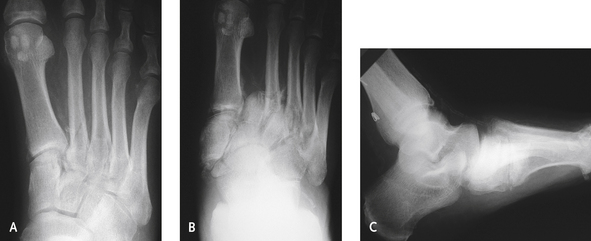

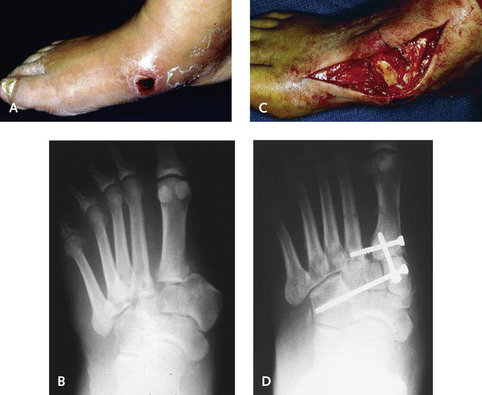

During the acute phase, some absolute indications for surgery exist, including medial dislocation of the cuneiform or navicular, which will lead to skin necrosis (Figure 14-4). Initially, the associated swelling masks the bone prominence, but with resolution of swelling, a pressure sore develops or full-thickness skin loss occurs (Figure 14-5). My experience suggests that if the dislocation is diagnosed early on in the evolution of the arthropathy, surgery will minimize the likelihood of deformity. The patient has to remain non–weight-bearing regardless of the type of treatment, and provided that the foot is not ischemic, surgery is preferable. With complete bone extrusion, operative reduction and stabilization will be necessary to prevent subsequent deformity. In patients with these acute fracture-dislocations, the issue is whether the potential morbidity of surgery outweighs the likelihood of later complications (Figure 14-6).

OSTECTOMY

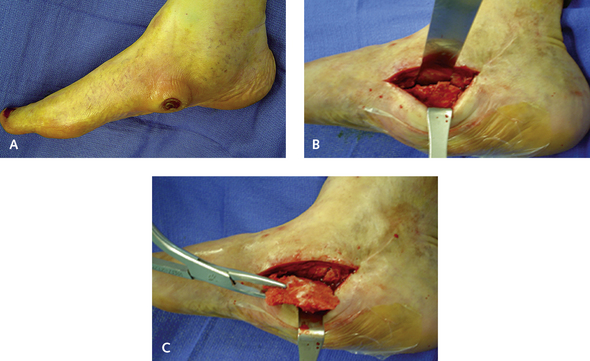

Technically, the ostectomy is not difficult to perform, and the only issue is to try to minimize postoperative soft tissue problems. Rarely, I approach the ostectomy through the open ulcer. Usually, the skin has healed over the ulcer from a total contact cast program, and the incision is made off the weight-bearing surface of the foot, either medially or laterally. Large skin flaps are preserved, and full-thickness dissection using a broad periosteal elevator should be performed to reach the prominence. I use a combination of an oscillating saw, osteotomes, and a rongeur to create a contoured surface of the plantar weight-bearing foot amenable to ambulation (Figure 14-7). It is imperative not to resect too much bone, or the result will be instability, which is particularly likely on the inferior aspect of the midfoot joints. A large, solid neuropathic bone mass may be present but is uncommonly seen; resection of the undersurface of unfused midfoot joints may have the effect of worsening the deformity and secondarily exacerbating the deformity.

TECHNIQUES, TIPS, AND PITFALLS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree