Fig. 4.1

Ancient Egyptians used kohl pencil to enhance their eyebrows. (Ancient Egyptian women wearing kohl, 1420 − 1375 BC. Mural in a tomb in Thebes. Image courtesy of 10,000 Meisterwerke der Malerei, a compilation by The Yorck Project provided by Directmedia; available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kohl_(cosmetics))

Fig. 4.2

European upper-class women in the fifteenth century attempted to make their foreheads appear higher by manual removal of the hairline. (Rogier van der Weyden, Portrait of a Lady, 1460. Oil on panel, 34 × 25.5 cm. Image courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portrait_of_a_Lady_(van_der_Weyden)

Fig. 4.3

Women in sixteenth century England covered their faces with ceruse to recreate Queen Elizabeth’s pallor. Ceruse was later discovered to be poisonous. (Unknown painter, Coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth I of England, 1600–1610. Oil on panel, 127.3 × 99.7 cm. Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London; available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian_ceruse)

Fig. 4.4

In the seventeenth century, larger women were considered goddesses. (Peter Paul Rubens, Venus at a mirror, 1615. Oil on canvas, 124.5 × 105.5 cm. Image courtesy of the Liechtenstein, The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna; available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venus_with_a_Mirror)

A review of popular images of the female body in Western culture over the course of the twentieth century provides an excellent example of evolution of popular norms of beauty [60]. Beginning in 1890 and into the early 1900s, the Gibson girl, created by illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, personified the ideal of feminine beauty [60]. The Gibson girl was slender and tall, with a voluptuous bust and wide hips accentuated by a cinched waistline and corseted torso (Fig. 4.5). After World War I, at the onset of the “roaring” 1920’s, the flapper silhouette became popular—a flat-busted, curveless, and boylike figure (Fig. 4.6). The flapper phenomenon ended with the Great Depression, when the desire for more feminine sexual characteristics, such as bustiness, returned, and big-breasted cinema stars, such as Mae West and Greta Garbo, became sex symbols. During the World War II, as the hemlines of skirts continued to shorten and high heels came into fashion, the legs joined the breasts as symbols of beauty and eroticism. Popular pinups in World War II depicted models with hemmed stockings, garters, and high heels capping seemingly endless legs. Post-World War II, the 1950’s Hollywood and fashion industry perpetuated this voluptuous ideal of beauty with the assiduously produced hourglass look of big-studio starlets like Marilyn Monroe. During the “sexual revolution” of the 1960s, this voluptuous look gave way to a thin and androgynous figure that closely resembled the ideal of the 1920s. A 97-pound English model nicknamed “Twiggy,” with a minimal chest and short hair, embodied this newly evolved ideal body shape. Svelte became à la mode: studies of Miss America pageant contestants and Playboy centerfolds from 1960 to 1978 depict a significant downward trend in average body weight over the 2 decades [61]. Although physically fit “hard-bodies” were briefly idealized in the 1980s, the waif look in the 1990s became popular again, especially in the world of high fashion typified by models such as Kate Moss. This thin trend continued and persists today in fashion and in much of Hollywood.

Fig. 4.5

At the turn of the twentieth century, the illustrator, Charles Dana Gibson, personified the ideals of feminine beauty in his drawings. The Gibson girl was slender and tall with a voluptuous bust and wide hips accentuated by a cinched waistline and corseted torso. (Charles Dana Gibson, “Gibson Girls,” circa 1900. Engraving after original drawing, titled Picturesque America, Anywhere Along the Coast, original drawing dated 1898. Image available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gibson_Girl)

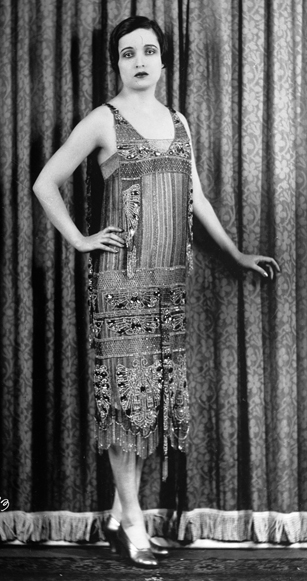

Fig. 4.6

In the 1920’s, the flat-busted, curveless, and boylike figure of the flapper became popular. (Actress Alice Joyce, February 1, 1926. Press photograph from the George Grantham Bain collection. Image courtesy of United States Library of Congress; available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flapper)

Cultural Influences

Although beauty has an evolutionary basis, the importance of local conditions and cultural transmission can affect its perception. Ethnic groups differ on many innate morphological features such as the shape of the nose and eyes. They also differ based on acquired and culturally determined features such as ornamentation, hairstyle, and face alteration [62]. Although certain acquired features may be quite unappealing to an outsider, these culturally determined attributes often play an important role in group membership and status within a given society [62]. Body ornamentation is culture specific. In African tribes, a lower lip plate can be seen combined with the removal of the two lower front teeth (Fig. 4.7). When a tribal chief was once asked the reason for them, he answered: “For beauty! They are the only beautiful things women have; men have beards, women have none. What kind of person would she be without this? She would not be a woman at all.” [63]. In the Kayan Tribe in Thailand, the elongation of a woman’s neck is considered beautiful (Fig. 4.8).

Fig. 4.7

Beauty ideals fluctuate across cultures. Body ornamentation is culture specific. In the Mursi tribe in Ethiopia, women place a plate in their lower lip and excise their two lower front teeth. (Mursi woman and her baby in Mago National Park, Ethiopia, November 12, 2012. Photograph courtesy of Bernard Gagnon; available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lip_plate)

Fig. 4.8

In the Kayan tribe in Thailand, women wear neck rings. The elongation of the woman’s neck is considered beautiful. (A Kayan woman in Thailand displaying her neck rings. Photograph courtesy of Steve Evans; available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neck_ring)

In 1874, Charles Darwin performed a rudimentary cross-cultural study and found that men use widely varying criteria to judge attractiveness in women. His conclusion was that there was no single standard of beauty with respect to the human body [63]. While research since the time of Darwin strongly suggests that there are universal standards to beauty, as outlined in the previous chapters, there may still be some truth to Darwin’s initial assertion. Perceptions of human beauty do vary slightly from culture to culture. Studies have shown that male preferences for female body fat, female preferences for male facial masculinity, and even the relative importance of pleasing facial features over bodily features differ across cultures. In a recent study, computerized images of a model’s face were generated with the ability to alter certain characteristics, namely nose shape and the projection of the lips and chin [64]. These modifiable images were sent to more than 13,000 plastic surgeons and laypeople in 50 different countries who were then able to virtually create a face that they felt to be the aesthetic ideal. Ideal facial configurations were found to be highly dependent on the individual’s cultural and ethnic background, providing evidence that ethnic, demographic, and occupational factors significantly impact a person’s perception of beauty [64].

Historically, studies have perpetuated the notion that low waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) is a reliable marker of beauty and indicator of mate preference [62]. However, these studies draw their data largely from subjects in industrialized nations. Certain foraging societies have been shown to disregard low WHR in preference for heavier set women. Men of the Matsigenka of Peru and the Hadza of Tanzania, cultures that practice swidden agriculture (a physically demanding form of subsistence farming) and that are largely isolated from Western culture, give overall consideration to general size rather than ratio, preferring heavier women when expressing preference for mates [65, 66]. The Shiwiar forager-horticulturalist men of Ecuadorian Amazonia use both WHR and body weight in assessments of female attractiveness, also preferring higher body fat women [67]. In fact, the majority of the world’s cultures have perpetuated ideals of feminine beauty that include plumper women [68]. This is in contrast to Western societies where thinness is valued. Although a low WHR is a better predictor of women’s attractiveness, in a US sample, thinness was so highly valued that 24 % of women and 17 % of men reported to be willing to give up 3 years of their lives to be thinner [69]. In the USA, women and men seek out ways beyond weight loss to decrease fat and cellulite including liposuction, cryolipolysis, ultrasound, laser-assisted lipolysis, radiofrequency, and topical herbs [70]. An explanation for this discrepancy between foraging societies and more industrialized western societies is that body fat is attractive in societies in which food resources are limited and not storable [71].

Female preference for masculine facial features also differs across cultures. In Jamaica, where infectious disease is prevalent and male parental investment is often less pronounced than in other countries, researchers found a greater female preference for masculine facial features than in the UK [72]. In this study, Jamaican and British participants were presented with masculinized and feminized digital representations of male and female faces. In contrary to the British counterparts, Jamaican women consistently preferred more masculine faces.

The relative importance placed on the maintenance and presentation of the face and the body varies significantly across cultures. In one study, researchers compared advertisements for beauty products in Taiwan, Singapore, and the USA, and they found that advertisements directed at the improvement of women’s hair, skin, and face occupied the greatest proportion of ad space in Singapore (40 %) and Taiwan (49 %), while clothing advertisements occupied the largest proportion of ad space in the USA (54 %) [73]. The study also found more frequent instances of sexualized beauty present in US advertisements than in those of the East Asian countries. Even within the USA, Asian American culture may be more focused on the face than body. The various types of cosmetic surgery sought in the USA appear to be racially and ethnically focused [74]: Asian American women more often request “double eyelid surgery” whereas European American women comparatively prefer body-sculpting surgery such as breast augmentation and liposuction. Clearly, cultures will evolve differently and preferences may become selected for based on conscious and unconscious strategies [72].

Impact of the Mass Media and Globalization

Perceptions of attractiveness may also reflect societal ideals dictated by the apparent preferences of the mass media and fashion industry [75]. Englis et al. argue that advertising agencies and fashion and beauty editors act as cultural “gatekeepers” who, by virtue of their influence over product promotion, clothing design, and casting, shape the ideals of beauty that will be adopted by the society that serves as their audience [76]. Carefully staged images of men and women, often airbrushed or even computer generated, become icons of beauty which in turn act as powerful ideals for consumers. In this way, the media creates false and adjusted beauty standards. When men were exposed to extremely attractive stimuli (television show with three strikingly attractive females) in both a field study and laboratory setting, they later rated an average female as significantly less attractive than did a comparable control group [77]. In western societies, the continuing presentation of ultra-thin models can lead to the adoption of this beauty ideal. In a study investigating how perceptual experience modulates body aesthetic appreciation, although thin bodies received higher “liking” judgments than round bodies overall, a very brief exposure to rounder bodies lessened this strongly polarized preference [78].

Unachievable ideals of beauty are at least becoming more diverse. Although it may be possible to choose a woman who personified beauty during a point when Western society was dominated by certain ideals—Marilyn Monroe in the 1950s or Twiggy in the 1960s (refer to Historical influences)—Western society today is more inclusive and mass media has become more fragmented as it targets a wider range of ethnicities and cultures. In the music industry, enormously popular pop and rhythm and blues artists, such as Beyonce Knowles, Taylor Swift, and Shakira, whose music is synonymous with their sex appeal, demonstrate this phenomenon. Barbie® dolls, paragons of beauty for generations of young girls and historically dominated by purely Caucasian ideals, are now sold in variations of skin, hair color, and facial features.

However, while fractionation and the increasing reach of the mass media may have expanded our notion of beauty, its broad reach and influence may have also imposed more uniform standards of beauty than previously existed. Western influence on the ideal Japanese woman’s eye shape provides an apt example. A study examining Bijin-ga portraits, or Japanese portraits of beautiful women, compared differences in the eye shapes and sizes of women in the Meiji Period (1868–1912) and modern day Japan (after World War II) to find significant differences in the eyes that trend toward Western ideals [79]. This may, in part, explain the beauty ideals in today’s Asian American culture; the cosmetic surgery most often requested by Asian Americans is “double eyelid surgery” [74].

Beauty as a Complex Construct

The concept of beauty is complex. The perception of what is beautiful changes depending on the individual, society, or historical period. Personality, relationships, culture, and media shape beauty standards to create individualized ideals. Although physical characteristics of beauty may be innate, other aspects are influenced by particular conditions, experiences, and surroundings. According to one author, any person can increase his or her attractiveness by maintaining good eye contact, acting upbeat, and dressing well [80]. Despite the breadth of scientific research that has sought to standardize beauty, we acknowledge that Darwin was right as much as he was wrong; there is no precise recipe for beauty [63, 81]. The judgment for what is beautiful is, at least in part, subjective. Hungerford’s famous phrase “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” continues to ring true. However, what happens to the evaluation of beauty when the beholder is also the target? This is, in effect, the paradigm for body image. The factors that influence our body image and promote body image dissatisfaction are the subjects of the next chapter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree