(1)

Department of Dermatology and Allergology Biederstein, Technische Universitaet Muenchen (TUM), Munich, Bavaria, Germany

(2)

Christine Kuehne Center for Allergy Research and Education (CK-CARE), Hochgebirgsklinik (High Altitude Hospital), Davos, Switzerland

5.1 Glucocorticosteroids

The introduction of topical glucocorticosteroids into dermatology may be regarded as the greatest progress in the treatment of numerous skin diseases in the second half of the twentieth century (Sulzberger and Witten 1952).

Only rarely, systemic glucocorticosteroids are necessary in atopic dermatitis. It is almost always possible to treat an acute flare (see above) with topical treatment, maybe supported by intravenous antihistamines.

Still today—in spite of increasing skeptical and critical attitude of many patients—topical glucocorticosteroids are in the focus of treatment of atopic dermatitis (Akdis et al. 2006; Darsow et al. 2010; Hoare et al. 2000; Ring et al. 2012; Werfel et al. 20a08b, 2009). In the physician’s desk reference of Germany (“Rote Liste”), there are over 300 preparations under the heading “Dermatics/Corticosteroids” in various application forms, among them ca. 70 combination preparations with various galenic characteristics (systemic corticosteroids are not enlisted here).

5.1.1 Effects

The pharmacological effect of glucocorticosteroids is bound to specific molecular structures (Fig. 5.1). By introduction of halogen atoms (e.g., fluor or chlorine) in position 9 alpha, the biological activity is considerably increased, similarly in position 6 alpha. Furthermore, esters or acetonides lead to a stronger efficacy of topical glucocorticosteroids.

Fig. 5.1

Chemical structure of glucocorticosteroids

Glucocorticosteroids have numerous effects on the skin (Fig. 5.2). The steroid molecule after absorption is bound to a cytoplasmic receptor in the keratinocyte which then is included in the nucleus where it influences the transcription of messenger RNA. Steroids have both stimulating and inhibiting effects. The name derives from the best-known effect, namely, the mobilization of muscle glycogen and enhancement of neoglucogenesis from amino acids. In fatty tissue, glucocorticosteroids induce lipolysis; in various tissues, they induce an involution in the direction of atrophy, especially in lymphatic cells, bone, and skin. These effects are mainly due to an inhibition of DNA synthesis (Hatz 1998).

Fig. 5.2

Effects of glucocorticosteroids on the skin are intrinsically connected with undesired side effects

Via a gestagen-like effect, similar to progesteron, they also can induce sometimes serious psychologic alterations such as sleep loss, depression, euphoria, and nervosity.

Among the many variants of glucocorticosteroids, several substances have been developed with the aim to improve absorption efficacy while, on the other hand, minimizing side effects. Modifications include the hydroxylation, or adding further carbon side chains or adding halogenides. Methylprednisolone aceponate with double esterification increases the lipophilicity and thus the penetration into the epidermis. In several preclinical and clinical studies, this substance has shown to have a good efficacy safety profile (Luger 2010).

These differences in strength of efficacy have to be considered in the practical use. Table 5.1 shows a personal arbitrary classification for daily use. In my experience, only products from class 1 or 2 (mild to moderate) are necessary for atopic dermatitis; for other skin diseases, we very well need stronger preparations!

Table 5.1

Classification of topical glucocorticosteroids according to their strength and side effects (Ring 2005)

Class | Substance |

|---|---|

I (not halogenated) | Hydrocortisone, hydrocortisone butyrate, hydrocortisone acetate, budesonide, methylprednisolone aceponate, prednisolone, prednicarbate |

II (weakly fluorinated) | Fluorcortinbutyl ester, clobetasone butyrate, fluticasone propionate, mometasone furoate |

III (medium strength) | Betamethasone valerate, triamcinolone acetonide, flumethasone pivalate, flucortolone, dexamethasone |

IV (strong) | Betamethasone propionate, fluocinolone acetonide, diflucortolone valerate |

V (very strong) | Fluocinonide, halcinonide, clobetasol propionate |

More important than the selection of the substance is the choice of the adequate galenics (see above Sect. 4.3). In the acute phase, topical glucocorticosteroids can be used twice daily; later on, the application once daily is enough (Turpenen 1991; Luger et al. 2004). In the acute phase, the application as wet wrap has proven helpful (Devillers et al. 2002; Hindley et al. 2006; Schnopp et al. 2002; Ring et al. 2012).

In therapy-resistant chronified lichenified lesions, occlusive treatment can be necessary. One should be careful with the application of glucocorticosteroids in intertriginous areas (axilla, anogenital area) because side effects will appear faster (e.g., striae distensae) (Furue et al. 2003).

5.1.2 Side Effects

5.1.2.1 Skin Atrophy

Systemic side effects of glucocorticosteroids are extremely rare in the treatment of atopic dermatitis (Table 5.2) (Bode 1980). However, patients continuously are confused by these phenomena through wrong information by newspapers and other patients. There seems to be sometimes a real “corticophobia” which takes away a lot of time in the daily physician/patient interaction.

Table 5.2

Side effects of systemic glucocorticosteroids

Endocrinologic | Diabetes mellitus Catabolic metabolism Osteoporosis Disturbance of lipid metabolism Electrolyte disturbance Hypophyseal suppression (Cushing) Hypertension |

Gastrointestinal | Gastritis, ulcus ventriculi |

Immunosuppression | Weakened defense against infections |

Neurologic | Myopathy (muscle weakness) Neuropathy Psychic alterations Behavioral change, sleep loss, nervosity, “withdrawal symptoms” |

Ophthalmologic | Cataract Glaucoma |

Hematologic | Thromboembolic complications |

More important are side effects of topical glucocorticosteroids on the skin (Table 5.3). Besides very rare cases of cortisone allergy, all these side effects more or less are directly connected to the pharmacological effect of the substance. The disturbance of the osteofollicular keratinization leads to the formation of comedones and steroid acne. The inhibition of proliferation and regeneration of epidermis induces atrophy; the degeneration of collagen and elastic tissue induces senile elastosis as well as the formation of telangiectasia, purpura, and ecchymosis as well as striae distensae (stripes of pregnancy) (Table 5.3 and Fig. 5.3).

Table 5.3

Side effects of topical glucocorticosteroids

Striae distensae |

Atrophy (all skin layers) (“pseudo-cicatrices stellaires”) |

Embolia cutis (after intramuscular injection) |

Increased light sensitivity |

Cutis punctata linearis colli |

Telangiectasia, rubeosis steroidica |

Pigmentation alteration |

Hypertrichosis |

Purpura and ecchymoses |

Acne |

Hair loss |

Disturbance of wound healing |

Perioral rosacea-like dermatitis |

Granuloma gluteale infantum (Fig. 5.4) |

Contact allergy |

Fig. 5.3

Common side effects of topical corticosteroids in the skin. (a) Atrophy of the skin in atopic dermatitis. (b) Corticoderma after topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis. (c) Striae distensae after short-time application of topical corticosteroid

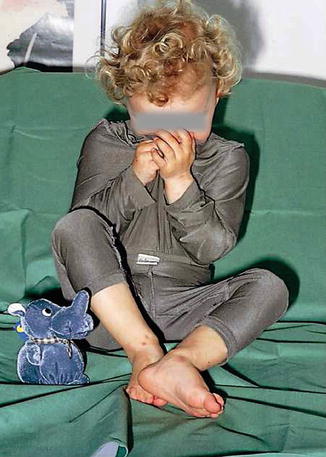

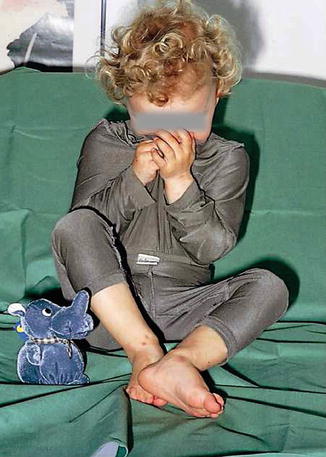

Fig. 5.4

Granuloma gluteale infantum in atopic dermatitis

5.1.2.2 Perioral Rosacea-Like Dermatitis

A special side effect of topical glucocorticoids is the so-called perioral rosacea-like dermatitis (perioral dermatitis) which occurs after the application of mostly halogenated glucocorticosteroids and—mostly in atopics—becomes manifest in the face as fine acute pointed papules and redness with burning sensation (little itch) (Fig. 5.5). Often the initial indication for the steroid treatment is no longer known, and the patients believe that the steroid is the only cure: Indeed, whenever the steroid is withdrawn, there is a rapid exacerbation which disappears immediately when the steroid is applied again. I explain to my patients—not quite scientifically—that in this phenomenon, “your skin is addicted to cortisone; we have to make a withdrawal procedure” (Fig. 5.6).

Fig. 5.5

Perioral rosacea-like dermatitis in atopic dermatitis

Fig. 5.6

Lipatrophy after intramuscular cortisone injection

5.1.2.3 Ocular Complications

The risk of ophthalmic complications, especially glaucoma and cataract, in atopic dermatitis treated with topical glucocorticosteroids was studied in 88 patients with facial and eyelid involvement. There were one patient with transient ocular hypertension and one patient with optic disk cupping as well as seven patients with the diagnosis of cataract, two corticosteroid-induced and four age-related ones, and one in relation to atopic dermatitis itself. These patients also had used systemic corticosteroids. The authors concluded that topical application of glucocorticosteroids per se is not related neither to the development of glaucoma nor of cataract; however, systemic glucocorticosteroids may lead to these complications (Haeck et al. 2011a and b).

5.1.2.4 Lipodystrophy

Furthermore, the rare but very unpleasant lipodystrophy after intermuscular injections of glucocorticosteroid crystal suspensions which can also lead to muscular atrophy has to be mentioned (Fig. 5.6).

Fig. 5.7

Chemical structure of topical calcineurin inhibitors

5.1.3 Diminishing the Dose (Tapering)

Corticosteroid therapy never should be stopped abruptly since this might lead to a rebound of the skin disease. A slow dose reduction until the final stop is indicated. Either the efficacy strength of the steroid or the frequency of application (tandem therapy) can be decreased by choosing different classes of substances. This can be done by alternating the steroid application with basic emollients in increasingly rarer steroid applications (4 days steroid, 3 days basic emollient until 2 days steroid, 5 days emollient or steroids only once a week). This regimen can be prolonged over longer time periods in order to prevent new exacerbations (Berth-Jones et al. 2003; Hanifin et al. 2002; Peserico et al. 2008). Similar principles have also been described for topical calcineurin inhibitors (see Sect. 5.2) and have been called “proactive therapy.” For this regimen, it is helpful that many steroid producers also offer steroid-free skin care basic emollients with the same ingredients.

5.1.4 Combination Therapy

The use of combined glucocorticosteroids with antibiotics or antimycotics is seen critically; however, sometimes such a combination can be useful. What should be avoided is the uncritical “triple therapy” (corticosteroid, antibiotic, plus antimycotic) instead of performing adequate diagnosis!

Specific prescriptions (magistral prescriptions) with individual mixtures of certain substances are helpful, especially also with regard to the individual estimation by the patient. However, a good pharmacist has to guarantee the galenic compatibility of the final emulsion; not everything can be mixed with everything.

5.1.5 Summary

The introduction of glucocorticosteroids in dermatology was the greatest progress for eczema patients in the second half of the twentieth century (Fig. 5.8). Systemic glucocorticosteroids only rarely have to be given in atopic dermatitis. The selection of the substances depends on the strength of efficacy but more upon the galenic characteristics. For atopic dermatitis, mostly mild to moderate strength steroids are adequate. The application of topical glucocorticosteroids in the correct vehicle should be timely limited and ended via a “tandem therapy.” Proactive strategies with once or twice weekly applications of the effective substance have proven helpful. The most important side effects of topical glucocorticosteroids include skin atrophy and the common manifestation of perioral rosacea-like dermatitis which occurs especially in young women after topical corticosteroids.

Fig. 5.8

Mechanism of actron of topical calcineurin inhibitors

5.2 Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors

The introduction of topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) in the early 1990s can be regarded as major progress in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. At the moment, two topical TCI are available, the substance tacrolimus from the mushroom Streptomyces tsukubaensis (brand name Protopic) and the semisynthetic ascomycin derivative pimecrolimus (brand name Elidel). Those substances also are sometimes called macrolactams because of their similarity in structure with macrolide antibiotics (Fig. 5.7).

Fig. 5.9

Child with silver-coated textile

5.2.1 Pharmacological Effects

TCI have similar effects as cyclosporin A (see Sect. 5.8) with inhibition of T cells by binding to the cytosolic immunophilin (FK506 binding protein) and inhibiting calcineurin phosphatase (Fig. 5.8). Therefore, signal transduction and transcription of several proinflammatory cytokines in lymphocytes is inhibited (Bornhoevd et al. 2000; Wollenberg et al. 2001); furthermore, other inflammatory cells, like mast cells or basophil leukocytes, are inhibited. Contrary to glucocorticosteroids, TCI do not inhibit the proliferation of keratinocytes nor fibroblasts, i.e., they have no atrophy-inducing side effects (Reitamo et al. 1998).

Fig. 5.10

Visualization of itch sensation in the brain in positron emission tomography (PET). Activation of motor areas in histamine-induced itch: gyrus precentralis and supplementary motor area (Darsow et al. 2000)

In addition to the anti-inflammatory effects, TCI seem to have a direct effect on skin nerves and become manifest in a strong antipruritic activity independent of the anti-inflammatory effect (Meingassner et al. 1997; Stuetz et al. 2001).

Tacrolimus is also in systemic use for organ transplantation. Newer developments include rapamycin (sirolimus) as well as everolimus. Different to TCI, they act via a cytosolic protein mTOR (molecular target of rapamycin) and induce immunosuppressive effects in the nucleus (Fig. 5.8).

Numerous studies have shown the efficacy of tacrolimus and pimecrolimus in atopic dermatitis (Paller et al. 2001, 2005; Reitamo 2001, 2003; Reitamo et al. 2002, 2005, 2007; Ruzicka et al. 1997; Luger et al. 2001). They are significantly effective compared to basic therapy; tacrolimus seems to be stronger than pimecrolimus (Paller et al. 2005). Overall, the efficacy is comparable to mild topical glucocorticosteroids of classes I and II. Tacrolimus is available in two concentrations (0.01 and 0.03 %) and in a relatively greasy ointment (Protopic). Pimecrolimus is available as 1 % cream and well accepted by the patients. For practical application of TCI, a similar procedure as used with glucocorticosteroids is helpful. One should not stop abruptly. From twice daily application, one goes down to once daily and finally in a way of interval therapy to twice or once weekly, which can be performed over longer time periods and has been called “proactive therapy”; for this procedure, tacrolimus has a special registration in Europe (Wollenberg et al. 2008).

5.2.2 Side Effects

TCI have advantages compared to glucocorticosteroids since they do not show the well-known side effects of topical glucocorticoids. They even can be used in perioral rosacea-like dermatitis or pityriasis alba (Rigopolous et al. 2006).

Acute side effects consist in burning sensations after the first application (more common with tacrolimus), which mostly subside during prolonged treatment. Occasionally patients observe severe burning dysesthesia when they drink alcohol; the mechanism of this reaction is not clearly established (Milingou et al. 2004). Contrary to topical glucocorticosteroids, pimecrolimus does not deplete Langerhans cells in the epidermis and thus seems not to influence the local immune response. Therapy with TCI in children did not show inhibitory effects on antibody responses after vaccination (diphtheria, tetanus, measles, rubeola, or pneumococci). There is also no increased risk of skin infections after topical application of TCI (Alomar et al. 2004; Kapp et al. 2002; Meurer et al. 2002, 2004; Ring et al. 2009; Wahn et al. 2002; Sigurgeirsson et al. 2015). When correctly applied, percutaneous absorption and systemic effects can be neglected. Whenever measurable blood levels have been detected, they were below 1 μg/mL, with a detection rate of 0.5 μg/mL. However, patients with the rare Netherton syndrome seem to be an exception; here higher percutaneous absorption rates of tacrolimus have been found (Reitamo et al. 2001; Undre et al. 2009).

A major concern with the use of TCI is the risk of cancer induction, which on the basis of theoretical considerations has been mentioned by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the USA in the spring of 2005 and led to the “black box warning” in the product information. The basis of this decision was an animal experimental study in hairless mice with well-known increased susceptibility to UV light effects and possible photocarcinogenicity, which was found for a higher (never commercially used) tacrolimus concentration in the sense of a shortened time until appearance of undefined “skin tumors” (Ring et al. 2005, 2008).

This model has been very controversially discussed; the study has not been reproduced by other groups. Therefore most expert committees or societies have recommended avoiding exaggerated sun exposure during a treatment with topical TCI (but also glucocorticosteroids).

In large and long-term observational and clinical studies of patients treated with TCI, no increased incidences of malignant tumors, lymphoma, melanoma, or nonmelanoma skin cancer have been observed (Arellano et al. 2007). In some studies, there were decreased prevalences of skin cancer in patients under TCI treatment, maybe due to better sun protection in this patient group (Luger et al. 2005; Ring et al. 2005).

There were no major serious adverse events in the study group. Furthermore, there was no influence of topical pimecrolimus on the development of normal immune responses after standard vaccination programs; thus, no clinically relevant systemic immunosuppressive effect was noted (Luger et al. 2015.)

In a prospective randomized open trial in over 2,000 infants, the efficacy and safety of pimecrolimus were investigated. Infants were attributed randomly to two groups at first appearance of atopic dermatitis: One group was treated with pimecrolimus 1 % cream as the first-line therapy, and the other group was treated with topical glucocorticosteroids as it used to be the standard some years ago. All children were observed over 5 years with regard to efficacy and safety. There was a similar and fast response to topical pimecrolimus therapy in infants treated with pimecrolimus compared to steroids. A rather high number of children never had to use topical steroids at all.

When disease was progressing, in the pimecrolimus group also topical steroids were used; in the steroid group, stronger preparations or systemic treatment was applied. There was no increased cancer rate (Sigurgeirsson et al. 2015).

5.2.3 Summary

The introduction of specific anti-inflammatory treatments like topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus can be regarded as a major progress since they do not exert atrophy-inducing side effects like topical glucocorticosteroids. In addition, they have a specific antipruriginous effect. TCI are especially valuable in eczema treatment in problem areas like the face or the anogenital area. They seem to be weaker in efficacy than topical glucocorticosteroids. TCI can also be used in a proactive regimen over long time periods in order to prevent exacerbations.

5.3 Antimicrobial Therapy

One of the pathophysiological characteristics of atopic eczema with definite practical clinical relevance is the high density of bacterial or otherwise microbial colonization of the skin surface, even in clinically uninvolved skin (see Sect. 3.4). Apart from acute superinfections (e.g., impetiginized eczema, eczema herpeticum), the mere colonization of the skin surface with pathogenic germs may contribute via various mechanisms to the maintenance of inflammatory skin reactions.

In the treatment, one has to distinguish between general antiseptic therapy and specific antimicrobial treatment by antibiotics, antimycotics, or virostatics.

5.3.1 Antiseptics

Antiseptics are substances which kill microbes of any kind or inactivate them; chemically, they belong to quite different structural classes.

Table 5.4 enlists various antiseptic compounds which will be briefly discussed.

Table 5.4

Antiseptics in the treatment of atopic eczema

Substance | Chemistry | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

Chlorhexidine | Biguanide | Antibacterial, low toxicity |

Povidone-iodine | PVP-iodine complex | Low sensitization potential, interaction with thyroid function |

Triclosane | Trichloro-hydroxydiphenyl ether | Good antibacterial effect, low irritancy, and toxicity |

Polyhexanide | Polyhexamethylene biguanide | Effective against MRSA, only available as solution and gel |

Octenidine | Octenidine dihydrochloride | Effective against MRSA, good mucosal tolerance, only solution |

Colorings Gentian violet | Methylrosanilinium chloride and para-dimethylamino-triphenylmethane, pyoctanin | Irritative effect in higher concentrations (>1 %), strong staining |

Clioquinol | Di-iodohydroxyquinoline | Good in combination with topical steroids, yellow staining, low risk of allergy |

Essential oils, e.g., tea tree oil | Farnesol | Good antimicrobial effect, high allergenicity |

Potassium permanganate | KMnO4 | Oxidative effects, to be used in bathtubs, staining effects |

Sodium hypochlorite | “Bleach bath” | To be used in baths |

Silver | Silver ions | Broad spectrum antiseptic low allergenicity, can be used in textiles |

Chlorhexidine is a cationic bisbiguanide with a relatively low potential of allergic sensitization which shows good effects in a 1 % solution as chlorhexidine digluconate. It is useful for application in intertriginous areas and skin folds (Stalder et al. 1992).

Povidone-iodine can be used at large surfaces of infected or burnt skin; for eczema, it plays a minor role; however, it is used in small areas when they are eroded and superinfected.

Triclosan is effective in vitro against S. aureus, Klebsiella, and Proteus species and also has antimycotic activity. It exerts mild antibiotic effects which may give rise to the development of resistance. Triclosan can be mixed well in a water-in-oil emulsion and has anti-inflammatory effects. It can be used for a long-term treatment combined with adequate basic therapy (see Sect. 4.3).

Polyhexanide is a polymerized form of chlorhexidine which originally was used as surface disinfectant in the food industry. Its antimicrobial effect is due to disturbance of membranes and denaturation of microbial proteins. It is used for antisepsis in wound treatment; rare cases of allergies have been reported. It is also effective against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Octenidine is used for disinfection in surgery and as an antiseptic cleansing agent for oral hygiene with good compatibility. Until now, it is only available as solution.

Colorings have been used in topical antimicrobial therapy for decades; most of them are triphenylmethane dyes with broad antimicrobial activity (Brockow et al. 1999b). Due to difficulties to produce large amounts in adequate purity and decreasing commercial interest, colorings often are no longer offered by the producers. The most commonly used colorings are gentian violet (crystal violet, pyoctanin) which is used in intertriginous areas in low concentrations (0.1–0.5 %). The red substance eosin can be used as 1 % solution in oozing eczema lesions. The disadvantage is the intense staining potential on skin and textiles, which has to be discussed with the patient before treatment.

Clioquinol is effective in combination with topical glucocorticosteroids, especially in combination with color therapy in nummular variants of eczema.

Essential oils have a high representation and popularity in the lay press. As a matter of fact, they contain natural antimicrobial substances with also anti-inflammatory properties. However, some of them have a rather high potential of allergenicity, especially tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia).

Silver nitrate (AgNO3) has been used for decades in wound treatment and in high dilution as an antiseptic.

5.3.2 Antimicrobial Textiles (Functional Textiles)

A new development can be seen in silver-coated textiles where the fiber—e.g., cotton—is coated with antiseptic substances, e.g., silver. Silver textiles have been used in atopic eczema and were able to significantly reduce colonization of the skin with S. aureus, leading to a marked improvement of eczematous skin lesions as measured in the SCORAD without additional therapy (Gauger et al. 2003) in a placebo-controlled trial.

Silver ions have a broad spectrum of antiseptic properties and do not induce development of resistance. Allergies against silver are almost unknown. One problem that has not quite been finally solved yet is an eventual absorption of silver ions in inflamed skin (Pluut et al. 2015). The acceptance of silver textiles from the side of the patients is very good (Gauger et al. 2006) (Fig. 5.9).

Fig. 5.11

Double-blind study with subcutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT) with grass pollen extract in homozygous twins with atopic dermatitis (left verum, right placebo) (Ring 1982b)

Apart from silver ions, also other antiseptic substances or detergents have been bound to textile fibers in order to produce antimicrobial textiles like benzalkonium chloride (Schnopp and Ring 2003; Jaeger et al., in prep).

5.3.3 Antibiotic Therapy

5.3.3.1 Systemic Antibiotic Therapy

As long as there is only colonization of skin surface without clinical signs of an infection, there is no indication for systemic antibiotic therapy in eczema (Werfel et al. 2009). In impetiginized eczema, especially with large surfaces involved, a short-time systemic antibiotic has proven helpful, especially with cephalosporins of newer generations (cefuroxime, cefadroxil, cefotiam) or penicillinase-resistant penicilliums (oxacillin, flucloxacillin, dicloxacillin) (Boguniewicz et al. 2001; Ewing et al. 1998; Weinberg et al. 1992). In cases of penicillin allergy, macrolide substances or gyrase inhibitors or clindamycin can be used.

5.3.3.2 Topical Antibiotics

A topical antibiotic therapy is always connected with the possible risk of development of resistance and therefore has to be indicated. First antiseptic measures should be used. There is also the risk of a contact sensitization especially for neomycin, tetracycline, or polymyxin (Wilkinson 1998).

Fusidic acid is the substance of first choice when topical antibiosis is required; it inhibits staphylococci in low concentrations and is also active against MRSA (Hjorth et al. 1985; Ramsay et al. 1996). Unfortunately, there is an increasing resistance against fusidic acid to be observed. In impetiginized areas, especially in the face, a combination of fusidic acid with topical glucocorticosteroids can be used.

Mupirocin is used as a nasal ointment and effective against S. aureus carriers. It is used prophylactically (Lever et al. 1988).

Combinations of antibiotics with glucocorticosteroids are often used; however, it is questionable whether the antibiotic really brings additional effects. Most of clinical trials have not shown a significant advantage of combined topicals compared to the pure glucocorticosteroids (Korting 1995; Leung 2003).

In impetiginized eczema, the application of topical therapeutics is crucial. We recommend the procedure of “wet wraps” (see Sect. 4.4). An antiseptic substance like polyhexanide 0.2 % or chlorhexidine 0.5 % is applied in a wet wrap. This, together with a wet wrap of basic treatment or steroid, is placed on top and fixed by a commercially available tube bandage. Over this, a second dry tube bandage is fixed. The substances should remain for several hours, and the wet wraps should be continually moisturized (Abeck and Ring 2002).

5.3.4 Antimycotic Therapy

In seborrheic skin areas, sometimes patients have a predilection for eczema together with the growth of the opportunistic yeast Malassezia furfur (head and neck dermatitis). Here a therapy with antimycotics, e.g., ketoconazole, but also ciclopirox olamine is effective and leads to the improvement of eczematous skin lesions (Broberg and Faergemann 1995; Mayser et al. 2006; Scheynius et al. 2002). Systemic antimycotic therapy is rarely indicated. Some authors recommend combined antimycotic and antibacterial therapy in all forms of severe atopic dermatitis. It is natural that superinfection with Candida albicans, especially in intertriginous areas, or dermatophytes (Trichophyton) should be treated with antimycotics.

5.3.5 Antiviral Therapy

Herpes simplex infection in atopic eczema can give rise to the serious disease of eczema herpeticum (see Sect. 3.4). In these cases, systemic antiviral therapy, best with three times daily intravenous infusions of acyclovir 5 mg/m2 or 15 mg/kg body weight, is the method of choice. In cases of relapses, long-term prophylaxis with valacyclovir is recommended.

Infections with molluscum contagiosum are not rare in atopic dermatitis and may give rise to involvement of large skin surfaces and special localizations (genital area), which makes treatment difficult. Careful removal and cryotherapy are the most commonly used treatment options.

5.3.6 Vaccination and Atopic Dermatitis

It is one of the most commonly asked questions whether patients with atopic dermatitis should be vaccinated like normal children. While this was a debate some decades ago, this question can now be answered clearly with “yes.” There is not only no increased risk, but it is recommended to perform vaccination programs especially carefully in patients with atopic dermatitis since they are more at risk than other persons (James et al. 1995). The only caution which has to be observed is the time point of vaccination: One should not immunize during an acute eczema flare (see Chap. 6).

This also holds true for the new opportunities of vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV); there have been single reports of exacerbation of eczema after vaccination with Gardasil and Cervarix, which, however, were spontaneously resolving.

Patients with atopic dermatitis have an increased risk after smallpox vaccination with scarification to develop eczema vaccinatum. That is why this classic vaccination against Variola vera was contraindicated in atopic eczema (see Sect. 3.4). With a newly developed vaccine using the modified virus Ankara (MVA) subcutaneously, it is possible to achieve immunogenicity with good compatibility also in patients with atopic eczema (Darsow et al., in prep.).

5.3.7 Summary

Antimicrobial strategies are important not only in the treatment of acute infections but also generally in the prophylaxis with regard to the high density of colonization of the skin surface with pathogenic germs in these patients. Generally antiseptics are used like triclosan in the acute treatment or clioquinol. Functional textiles coated with silver or other antiseptics represent an elegant method without using systemic or topical drugs (“textiles as drugs”). In severe cases, systemic antibiotic or antimycotic treatment in head and neck dermatitis can be used. The commonly discussed question whether patients with atopic dermatitis can be vaccinated like normals can be answered with a clear “yes.” There are only considerations with regard to the time point. One should not vaccinate during an acute eczema flare. Patients with anaphylaxis to ovalbumin should be tested with the vaccine before treatment.

5.4 Antihistamines

Histamine is the best-known mediator substance of IgE-mediated allergic reactions (Dale and Laidlaw 1910). After its release from activated mast cells or basophil leukocytes, it exerts the well-known proinflammatory effects rapidly on the vessels, superficial skin nerves, and smooth muscles. When injected in the skin, the classic Lewis triad can be observed:

Increase in capillary permeability of endothelial cells (plasma exudation, wheal formation)

Increase of perfusion by vasodilatation (erythema)

Axon reflex via superficial nerves (flare)

Together with these objectively visible effects goes the elicitation of the subjective symptom “itch.” Therefore it was natural to use antihistamines for the treatment of itch.

5.4.1 Histamine Receptors

Histamine exerts its effects via four different specific receptors: the H1 and the H2 receptors are also expressed in the skin, while H3 receptors are located in the central nervous system and H4 receptors on various leukocytes (Church 1999; Gutzmer et al. 2002, 2009; Simons et al. 2000; Simons 2004).

For most allergic symptoms, H1 effects are important; H2 receptors play a role for the effect on the gastric mucosa (acid secretion) as well as on the heart. There are also H2 receptors in the skin, facilitating flush reactions (Ashida et al. 2001; Cowden et al. 2010).

H3 receptors in the central nervous system allow an autocrine inhibition of histaminergic neurons, leading to increased vigilance.

Bovet and Staub introduced antihistamines into the therapy of allergic diseases in 1937 (Bovet and Staub 1934). In the following, under the term antihistamines, mainly H1 antagonists are mentioned.

5.4.2 Generations of Antihistamines

In practice, one often reads about various generations of antihistamines (Table 5.5); classic antihistamines with the well-known sedating side effects are the first generation. They also exert anticholinergic and antiserotoninergic effects. On the other hand, also some tricyclic antidepressants have antihistamine effects. There is a certain overlap which can be used in strongly pruritic conditions (Frosch et al. 1984; Murota et al. 2010; Wahlgren et al. 1990).

Table 5.5

Generations of antihistamines (H1 antagonists)

Classic sedating antihistamines | Newer, less sedating antihistamines | Metabolites of nonsedating antihistamines |

|---|---|---|

Dimetinden | Terfenadine | Fexofenadine |

Clemastine | Cetirizine | Levocetirizine |

Diphenhydramine | Loratadine | Desloratadine |

Alimemazine | Ebastine | |

Bamipine | Mizolastine | |

Cyproheptadine | Rupatadine | |

Dexchlorpheniramine | Azelastine | |

Hydroxyzine | Levocabastine | |

Doxylamine |

The so-called second-generation non-sedating antihistamines came into use 25 years ago (Bieber and Ring 1987); they do not cross the blood-brain barrier and thus have no sedating effects in the central nervous system, at least in normal doses. Some of these substances also have other antiallergic effects by acting on inflammatory cells such as eosinophil migration (cetirizine) or mast cell activation (loratadine) or superoxide formation of leukocytes (loratadine and azelastine) (Purohit et al. 2001; Simons et al. 2000).

Under the term “third generation,” substances comprise metabolites of well-known H1 antagonists which are no longer further metabolized in the liver or in the kidneys such as levocetirizine, desloratadine, and fexofenadine.

5.4.3 Effects of H1 Antagonists

Antihistamines are used all over the world as a standard treatment in the therapy of acute flares of atopic eczema; however, there is only limited evidence and only few well-controlled studies. This holds true especially for the older classical antihistamines with sedating properties like dimetinden, clemastine or doxylamine, and diphenhydramine. Maybe this can be explained by the fact that these substances have been introduced already 50 or 60 years ago before the era of randomized prospective controlled trials (Bovet and Staub 1934).

For the newer nonsedating antihistamines, there are a variety of studies which show positive effects against itch and atopic eczema (Hannuksela et al. 1993; Kawashima et al. 2003) as well as a high number of uncontrolled pilot studies (Klein and Clark 1999; La Rosa et al. 1994; Langeland et al. 1994; Murota et al. 2010; Ring et al. 2012).

5.4.3.1 Forms of Application

Usually antihistamines are applied systemically, most of them orally. There are only two preparations, namely, dimetinden and clemastine, which are available for intravenous injection. Apart from the topical application of medium-strength glucocorticosteroids in the correct galenics, the intravenous infusion of H1 antagonists is the standard therapy in treating pruritus and acute eczema flares in our department.

The sedating side effects can be neglected in the acute treatment of severe eczema flares in hospitalized patients or when applied in the evening.

Topical use of antihistamines as cream or gels for treating pruritus after insect stings is often advertised but probably only effective due to the cooling gel consistency of the vehicle. Due to these exsiccating properties of topical antihistamine preparations, they are not recommended in the treatment of atopic dermatitis.

5.4.3.2 Side Effects of Antihistamines

Classical H1 Antagonists

Here the sedating effects of classic H1 antagonists have to be mentioned first which also increase the side effects of other centrally active drugs or alcohol. Patients have to be informed about these side effects which become manifest in impaired speed of reactivity in traffic but also in occupational life when difficult machines have to be operated. I recall reports about severe traffic accidents by patients who continued a therapy with strongly sedating antihistamines (e.g., cyproheptadine, hydroxyzine) without or against medical advice. When an antihistamine therapy has to be continued over longer periods in everyday life, it is absolutely required to take a nonsedating antihistamine (fexofenadine) in the morning and sedating antihistamines (dimetinden) only in the evening (Behrendt and Ring 1990).

In small children, paradoxical reactions can occur if the sedating antihistamines stimulate an arousal reaction.

Due to the concomitant anticholinergic and antimuscarinic or antiserotoninergic effects, other side effects like difficulties in urination, attack of glaucoma, and dry mouth have to be considered, especially when other similarly acting drugs are given.

Second and Third Generations

The substances of the second or third generation are commonly called “nonsedating.” There are marked individual differences which are at the moment not totally explained by pharmacology but also are not due to a simple placebo or nocebo effect (Traidl-Hoffmann et al. 2006).

Some companies circumvent the problem of sedation in some countries by the simple recommendation to take the tablets in the evening after dinner. According to my opinion, the least sedating H1 antagonists are terfenadine (Bieber and Ring 1987) and its metabolite fexofenadine as well as desloratadine, which are also registered in the USA and permitted for pilots of aeroplanes since they do not interfere with vigilance.

5.4.4 Cardiac Arrhythmia

Some antihistamines of the second generation (astemizole and terfenadine) were associated with severe cardiac arrhythmias, especially the prolongation of the QT time; this was due to increased levels of the substance with concomitant application of other drugs metabolized via cytochrome P450 enzymes (e.g., azole antimycotics, macrolide antibiotics) but also naturally occurring substances in grapefruit juice. These effects are no longer observed with the metabolite fexofenadine. Astemizole has been withdrawn from the market in many countries.

Several authors recommend increasing the dose of antihistamines when the effect is not sufficient up to a fourfold dose (Zuberbier et al. 2013). However, there may also be increased side effects.

5.4.5 Pregnancy

A special problem is the treatment of pregnant women. There are few convincing studies giving clear-cut evidence. For safety reasons, most companies write on their informations to avoid intake during pregnancy. We often advise patients then to take the antiemetics with antihistaminergic effects such as dimenhydrinate which have been proven safe for millions of pregnant women.

Also preparations of the first generation which are registered for infants, like doxylamine, dimetinden, and clemastine, can be used. Also no negative reports are published regarding loratadine and cetirizine.

5.4.6 Other Antiallergic Substances

Other antihistamines, i.e., antagonists of H2, H3, or H4 receptors, do not play a role in the treatment of atopic dermatitis at the moment. Drugs from the group of psychopharmaceuticals with simultaneous antihistaminergic properties can be helpful in some patients with severe atopic eczema in long-term treatment like opipramol or doxepin.

Also the mast cell blocker ketotifen with antihistamine properties can be used; its effect usually takes some weeks (Falk 1993; Iikura et al. 1992). Also topically applicable derivatives of cromoglycates which have been proven to be active in respiratory allergy can be used as mast cell stabilizers after oral application in patients with atopic eczema and concomitant food allergy. The oral application of cromoglycate as capsule or powder four times a day before the meals can show good effects.

The leukotriene antagonist montelukast is known in asthma therapy and has shown beneficial effects in pilot studies in atopic eczema (Yanase and David-Bajar 2001).

5.4.7 Summary

Antihistamines are the standard therapy in the treatment of itch all over the world; however, there are few controlled studies in atopic dermatitis. Topical antihistamines can be neglected in atopic eczema. The sedating side effects of classic antihistamines may be beneficial in the acute treatment of severe flares in hospitalized patients or when given in the evening. Although increased plasma histamine levels have been found in atopic eczema, histamine does not seem to be the critical mediator of the atopic itch sensation.

5.5 Other Antipruritic and Anti-inflammatory Substances

Itch is the central symptom of atopic dermatitis and represents a major problem for most patients and their families, impairing or destroying the quality of life. We all know the poster which went around the world with the introduction of pimecrolimus (Elidel), showing an infant with a T-shirt with the inscription “If I don’t sleep, nobody sleeps!” as well as the pictures of bloody linen due to nightly scratch attacks.

5.5.1 Itch Sensation

Itch is the dysesthesia or unpleasant sensation which induces the urge to scratch. There is no better definition for this major symptom of allergic skin disease even 300 years after the first description by Hafenreffer (1660) (Ständer et al. 2015; Darsow et al. 1997b). When itch persists over a period of more than 6 weeks, it is called “chronic pruritus” (Yosipovitch and Bernard 2013). This condition occurs preferably in atopic eczema but also in a variety of other inflammatory skin diseases like psoriasis, scabies, and lichen planus or especially among the group of so-called prurigo diseases. In these conditions, often topical therapy is not enough, but systemic treatment strategies have to be considered with neuroactive medications like gabapentin and pregabalin (Yosipovitch and Bernard 2013) or antidepressants like sertraline, paroxetine, and mirtazapine (Ständer et al. 2015).

Chronic pruritus is not a rare condition. A cross-sectional observational study in 11,730 persons working in 144 companies in Germany showed a point preference of chronic pruritus of 16.8 %. There was an age dependence as this condition was more frequent in elderly patients (12.3 % in young adults aged 16–30 years, 20.3 % in persons aged 61–70 years) (Ständer et al. 2010).

In some cases of chronic pruritus, disturbances in iron metabolism have been suspected. If at all, the determination of ferritin may be helpful (Bharati and Yesudian 2008).

Itch and pain have in common that they only can be felt by the patient and not seen by other people. Thus they are difficult to be measured objectively. While patients with pain raise feelings of compassion immediately and everywhere, patients with itchy skin diseases are not taken seriously and often encounter the flippant sentence “just stop scratching!” This recommendation shows the complete ignorance about the dermatoneuropsychological mechanisms involved in pruritus (see Sect. 2.1).

5.5.2 Itch Research

While over many decades itch was regarded as the little brother of pain, this concept has been abandoned. Itch is mediated by a special subgroup of unmyelinated sensory C fibers and originates from the upper part of the dermis or the dermoepidermal junction. These fibers are sensitive to temperature but insensitive to mechanical stimulation. They express the vanillin receptor (TRPV1 = transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1), which is a nonselective ion channel expressed on keratinocytes and peripheral sensory C nerve fibers. Therefore also antagonists to this receptor, like PAC-14028, have shown to have an antipruritic effect in an atopic dermatitis model of mice (Yun et al. 2011).

These sensory nerves then transmit the sensation to dorsal route ganglia and from there via the spinal cord to the brain.

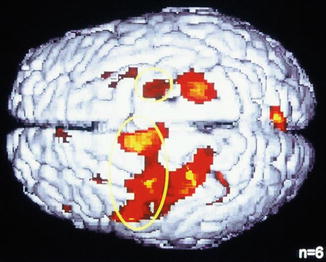

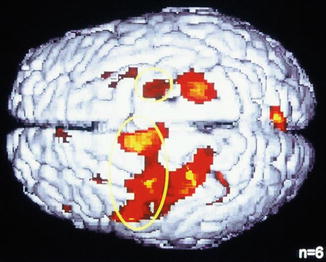

Recent imaging studies have shown that not only the thalamus is the major sensory organ, but also areas of the anterior cingulate cortex, the insula, and secondary somatosensory cortex areas are activated, as well as centers of the limbic system. Notably, the most visible feature of cerebral activation patterns after itch-inducing stimulation is the activation of the motor areas for the scratch response (Darsow et al. 2000).

For a long time, the search for the classical itch mediator substance has been going on (Table 5.6).

Histamine |

Serotonin |

Acetylcholine |

Neuropeptides (e.g., substance P) |

Cytokines |

Interleukin-2 |

Interleukin-8 |

Interleukin-31 |

Neurotrophin-4 |

Nerve growth factor (NGF) |

Tryptase |

Kallikrein, cathepsin S |

Platelet-activating factor |

Prostaglandins |

Leukotrienes |

Opioid peptides |

Another clinical condition going along with extreme itch is cutaneous amyloidosis, where deposits of amyloid and apoptotic keratinocytes are found in the papillary dermis. In the rare variant of the familiar primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA), it was found that the OSMR gene (oncostatin-M receptor beta) may play a major role since it involved, among others, interleukin-31, possibly then acting as major itch inducer (Tanaka et al. 2009 neu).

Unfortunately, itch research is far behind pain research. There are different qualities of itch. It is a well-known clinical experience regarding the morphology of skin lesions as well as the typology of scratch behavior. Using various questionnaires (Darsow et al. 1997a). With the Brest questionnaire the authors found significant differences in the quality of itch between atopic dermatitis, nonatopic eczema, urticaria, psoriasis, and scabies. There were also similarities that itch occurred more frequently over nighttime, following certain eliciting factors such as stress, dryness, and hot water. While application of cold was normally found to be beneficial in atopic dermatitis, the qualities of “stinging,” “pincing,” and “stabbing” were significantly more common than in the other dermatoses.

A major problem of pruritus research is its subjective character and the difficulty to be objectively measured. Usually visual analog scales (VAS) are used; however, they do not necessarily correlate well with the clinical appearance and intensity of the skin lesions (Darsow et al. 1997a). A new scale, the “5D itch scale,” has been proposed, registering the five dimensions of duration, degree, direction, disability, and distribution of pruritus as a better outcome measure for clinical trials (Elman et al. 2010).

Therefore mechanical devices have been developed to measure the scratching behavior with the so-called itch watch (Felix and Schuster 1975).

Other so-called actigraphic methods have been developed and found suitable to assess pruritus over nighttime (Murray and Rees 2011).

The scratch response may considerably contribute to the pathophysiology of itch-induced skin damage, as has been shown by early “inhuman” studies in putting a limb into plaster or fixing a child in the bed so that it could not move (Engman et al. 1936) (see above).

In murine experiments with NC/Nga mice—atopic dermatitis induced by repeated application of house dust mite—the contribution of scratch behavior to the induced eczema was remarkable. In the light of modern findings regarding IgE autoantibodies against epidermal proteins possibly liberated from keratinocytes by the scratch trauma, these observations gain a new importance (Yamamoto et al. 2009).

There is a strong psychosomatic interaction in the itch sensation. Therefore also psychological processes have to be considered in evaluating patients suffering from chronic pruritus. Personality factors, life events, and psychological stress may have an important role as external stimuli. Therefore biopsychosocial models have been proposed to better understand the vicious cycle of the itch-scratch response (Verhoeven et al. 2008).

While everybody is full of compassion when a person suffers from pain, itch is often not understood by the surrounding; people laugh and say, “just scratch.” In a cross-sectional study investigating the impairment in quality of life, 138 patients with chronic pain were compared to 73 patients with chronic pruritus with otherwise similar demographics. The authors used the health utility score as a measure of how much lifetime a person would be willing to give from his or her life expectancy to live without the condition and found that pruritus had a substantial impact on quality of life that may be comparable to that of pain (Kini et al. 2011).

A specially developed and validated pruritus-specific quality of life instrument, the ItchyQol, was developed (Desai et al. 2008).

In specially designed itch questionnaires (e.g., “Eppendorf Itch Questionnaire”), these differences can be measured (Darsow et al. 1997a, b).

With new imaging techniques like positron emission tomography (PET) or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the activation of central nervous areas in the brain during itch can be visualized (Darsow et al. 2000; Pfab et al. 2010a) (Fig. 5.10). It is interesting that besides sensory areas, which transmit the itch sensation, and the motor areas, which mediate the scratch reaction, also areas of the limbic system are activated, which points to an involvement of emotional reaction patterns.

Fig. 5.12

Clinical improvement in patients with atopic eczema under treatment with eicosapentaenoic acid or placebo in a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial: at the end, placebo was better than verum (After Ring and Kunz (1991))

Everybody knows that looking at an individual who scratches vehemently may also induce a scratch response in observers such that there is anecdotal evidence of “contagious” itch. This susceptibility to visual effects seems to be increased in atopic dermatitis. In a study, healthy volunteers and eczema patients were asked to watch a five-minute movie showing individuals suffering from obvious itch and scratching. The study participants received either saline or histamine as itch-inducing stimulus on the volar side of the forearm. Patients with atopic dermatitis scratched more frequently and reported a higher severity of itch while watching the movie compared to controls (Papoiu et al. 2011). Pruritus can be so severe that inpatient therapy becomes necessary. The establishment of special “itch clinics” has been proposed (Naldi and Mercury 2010).

The psychosomatic involvement in pruritus is immense (Manenti and Vaglio 2005). Therefore application of psychopharmaceuticals may be indicated in severe conditions, starting from doxepin, which also has a combined histamine H1 + H2 antagonistic effect, to tricyclic antidepressants (Hundley and Yosipovitch 2004) (Sect. 5.4.6).

5.5.3 Differences in Ethnic Populations

There may be differences in ethnic populations in itch perception on a global range with regard to various ethnic populations. This may be due to biologic factors like genetic predisposition to certain diseases, like amyloidosis or prurigo pigmentosa, which is more common in Asian individuals, or intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, which seems to be more common in Latin America. Also genetic polymorphisms in the interleukin-31 receptor may play a role. In Africans, a common condition is chloroquine-induced itch and primary bilharziasis (Tey and Yosipovitch 2010).

Also the response to capsaicin, a substance known to destroy sensory nerves and usually inducing an initial burning sensation, is different between ethnic groups: African Americans do not suffer the same degree of acute hyperalgesia and neurogenic inflammation as people from Spain or East Asia (Tey 2010). Also psychosocial and lifestyle factors may be involved in the itch process.

Due to the multitude of qualities and elicitors but also mechanisms of the itch sensation, a variety of antipruritic strategies are available, partly to be applied topically, partly systemically, or reflecting central nervous involvement with behavioral techniques (see Sect. 5.4) (Table 5.7).

Table 5.7

Antipruriginous agents

Topically applied substances | Systemically acting substances |

|---|---|

Local anesthetics | Antihistamines |

Glucocorticosteroids | Glucocorticosteroids |

Calcineurin inhibitors | Opiates and opiate antagonists |

Cannabinoid agonists | Antidepressants |

Capsaicin | Anticonvulsants |

Parasulfonates and others, e.g., bufexamac | Pain modulators Gabapentin, pregabalin |

5.5.4 Topical Antipruriginous Agents

Glucocorticosteroids are the most potent antipruriginous topical agents (see Sect. 5.1) as well as topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) (see Sect. 5.2). Besides, a variety of other substances are used therapeutically in order to diminish or treat itch sensation.

5.5.4.1 Local Anesthetics

Since itch sensation is mediated via excitation of sensory nerve fibers in the skin, local anesthetics naturally have an effect especially after intradermal or subcutaneous injection. This is no acceptable method for larger skin areas. Yet, in treating very circumscribed, chronic lichenified, or pruriginous skin lesions, the intradermal injection of local anesthetics can be helpful.

The topical application of local anesthetics as a lotion, cream, or ointment (e.g., Emla) is of little use in treating eczema, except for small circumscribed areas which can occur in the condition of notalgia paresthetica. The topical application of local anesthetics is connected with a rather high risk of sensitization and development of contact allergy.

5.5.4.2 Polidocanol

Polidocanol is a polymerized local anesthetic from dodecyl alcohol and ethylene dioxide. This substance with a molecular weight of 600 D can penetrate especially into inflamed skin and reaches sensory nerves and thus exerts an antipruriginous effect (Freitag and Hoppner 1997).

Polidocanol is used either as lotion (5 %), suspension, or cream. In very dry skin, it can be combined with 3–5 % urea (Hauss et al. 1993). This treatment can be self-applied by the patients as often as they wish. Thus one can spare topical glucocorticosteroid use.

5.5.4.3 Cannabinoid agonists

Endogenous cannabinoids play a role in the epidermal differentiation; receptors can be found on keratinocytes, sensory nerve fibers, and inflammatory cells. With cannabinoid agonists, antipruriginous effects can be observed. In a larger study, by the edition of the cannabinoid agonist N-palmitoyl ethanolamine in a differentiated basic therapeutic vehicle, a good effect in atopic dermatitis has been observed (Eberlein et al. 2009b).

5.5.4.4 Capsaicin

The vanilloid alkaloid capsaicin binds to the receptor TRPV1 on sensory nerve fibers and keratinocytes and leads to an inactivation of sensory nerve fibers. Acutely after application, there is a burning painful sensation. Capsaicin, the effective substance in tabasco sauce, is better used in strongly itching chronic lesions or in pruritus on nonaltered skin than in atopic dermatitis. When used, one should carefully watch the concentration and start with lower doses from 0.025 % over 0.05 to 0.1 %. Capsaicin should not be used in intertriginous areas, in the face, or on mucous surfaces.

5.5.4.5 Tar Preparations

Coal tar is one of the oldest treatments going back into the history of dermatology. It is a not very well-defined mixture of more than 1000 substances, among them also high concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Crude coal tar is produced when coal is heated without oxygen. Liquor carbonis detergens is made by extracting pix lithanthracis 1:5 with alcohol.

In earlier times, tar treatment with wood, slate, or coal tar was standard, especially the coal tar extract (liquor carbonis detergens) or pure coal tar (pix lithanthracis). These preparations have an anti-inflammatory and antipruriginous effect without the mechanisms being known.

Tar is a mixture of many, partly still unknown substances which originate in the process of distillation. Tar products have antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities. Especially phenolic components seem to have antipruritic effects (Munkvad 1989). The use of tar preparations is controversial in many countries due to the carcinogenicity observed in animal experiments (Pion et al. 1995).

While there is animal data of carcinogenicity of coal tar, there is still a controversy with regard to the safety of its use in humans. Therefore a large historical cohort study was performed studying the late effects of coal tar treatment in eczema and psoriasis, the Radboud study (LATER study) in 14,009 patients suffering mostly from psoriasis or eczema. The study covered observational periods between 13 and 43 years after treatment and found no increased values neither for skin cancer nor non-skin malignancies (Roelofzen et al. 2010). This supports earlier studies from Larkö and Swanbeck (1982) or Hannuksela-Svaan et al. (2000). The authors concluded that coal tar can be maintained as a safe treatment in dermatological practice. We use pix lithanthracis rarely and only under hospital settings and prefer liquor carbonis detergens which can be mixed with emollients to produce acceptable preparations for the patients. There may be a far revival since it counteracts Th2 reactions via aryl hydrocarbon (AH) receptor activation and STAT6 dephosphorylation (van den Bogaard et al. 2013).

5.5.4.6 Sulfonates

Sulfonates differ from tar since they are neither phototoxic, mutagenic, teratogenic, nor cancerogenic (Colcha et al. 1994; Diezel et al. 1992; Warnecke and Wendt 1998). They are produced from slant oil and represent ammonium bituminosulfonates. Effective substances have a thiophen ring structure. Sulfonates are used also in folliculitis or furuncles to attract neutrophil leukocytes.

In atopic eczema, lotions or pastes can be used which have beneficial effects in chronic lichenified skin areas.

5.5.4.7 Adstringentia

By alteration of superficial proteins in the epidermis, adstringentia of natural or synthetic origin can have beneficial effects, going along with exsiccation and anti-inflammatory effects. Most commonly used are preparations from oak bark or synthetic tannins on the basis of gallic acid (Tannolact, Tannosynt). Lukewarm hand baths together with tannic acid have shown to be beneficial in dyshidrotic hand dermatitis, as well as seat baths in perianal or perigenital eczema.

5.5.4.8 Etheric Oils

Among etheric oils, especially menthol is the best-known antipruriginous agent; its effect is mediated via direct action on the cold receptor fibers, thus overlaying the itch sensation. However, menthol is only available in solution, mostly alcoholic, and thereby has a very strong exsiccating effect. It is mostly used in acute conditions such as after insect bites where there is a very localized application area.

5.5.4.9 Others

A variety of other substances are used topically against itch or against eczema. The nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug bufexamac was promoted for some years to be as active as corticoids. However, due to the rather strong sensitizing properties, it is no longer in wide use (Christiansen et al. 1977) and has been withdrawn in most countries.

Topical antihistamines which are used as gels for insect stings are not recommended for the treatment of atopic eczema. This also holds true for topical preparations of doxepin or acetylsalicylic acid.

5.5.5 Summary

Itch is the most important symptom of atopic eczema and is in the center of successful therapy. The order to children “stop scratching” does not make sense since itch is defined as the unpleasant sensation eliciting the urge to scratch. The most important antipruriginous strategy is topical anti-inflammatory treatment with glucocorticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors. Besides, polidocanol in good galenic mixtures can have an antipruritic effect, equally cannabinoid agonist, tar, and sulfonate preparations as well as tannic acid which have been used in long-term treatment of lichenified areas and have been shown to spare topical corticosteroids.

5.6 UV Therapy

Phototherapy is a standard procedure in the treatment of many inflammatory skin diseases (Hönigsmann 2013). There are various modalities using different spectra of the UV irradiation (Bahvani et al. 2007; Hannuksela et al. 1985; Jekeler and Larkö 1991; Krutmann and Hönigsmann 1997; Reynolds et al. 2001):

Heliotherapy (this is the exposure to natural sunlight)

Broadband UVB (280–320 nm)

Narrowband UVB (311–313 nm)

UVA (320–400 nm)

UVA1 (340–400 nm)

Photochemotherapy using a combination of UV and psoralens, a photosensitizing agent (PUVA)

Radiation with visible light or blue light

5.6.1 Heliotherapy

Heliotherapy uses the exposure to natural sunlight under controlled conditions. It is crucial to test the patient’s photosensitivity (establishing the minimal erythema dose or checking Fitzpatrick’s light sensitivity skin types).

Heliotherapy is especially performed using climate conditions such as different altitudes, either very low beyond sea level as on the Dead Sea in Israel (Simons et al., Harari et al. 2000) or at high altitude like in Davos, Switzerland (1560 m) (Vocks et al. 2002; Engst and Vocks 2000).

The patient is told to precisely watch the time of sun exposure, starting with very short periods of two or three minutes and slowly increasing the time.

5.6.2 UVB Radiation

UVB radiation is the standard treatment of psoriasis and many inflammatory skin diseases; it has also a very special effect upon pruritus, also on pruritus without skin alteration.

Studying the individual wavelength within the UV spectrum, it has been found that 311 nm seems to be most effective, which is called narrowband UV radiation (Krutmann and Hönigsmann 1997). It has been shown that phototherapy with UVB is able to stimulate the production of antimicrobial peptides in the epidermis (Gläser et al. 2009b).

5.6.3 UVA Radiation

Through the development of special lamps, the application of long-wave UV spectrum was possible, especially through the development of infrared filters which lower the typical heat induction.

The mechanisms of UV radiation-induced immunosuppression are complex, some of them obviously occurring as a result of the repair processes induced by damage to epidermal structures, especially DNA, but also changes in membrane phospholipids and trans-urocanic acid and tryptophan (Gibbs and Norval 2013). Since the group of Margaret Kripke has shown that UV radiation can suppress delayed-type immunity against transplanted tumors in mice (Fisher and Kripke 1977), photoimmunology has been developed as an exciting branch of research (Krutmann et al. 2012). In the epidermis, Langerhans cells (CD1d) and langerin-positive CD103-negative dendritic cells migrate to the draining lymph node and stimulate the production of regulatory T cells. In experimental studies, it has been found that there are obviously two peaks within the electromagnetic spectrum which show especially marked effects with regard to immunosuppression, namely, in the UVB range around 310 and in the UVA range around 370 nm (Gibbs and Norval 2013).

Especially within the long-wave spectrum of UVA, the UVA1 part (340–400 nm) has been first studied by Krutmann et al. (1992; 1998). Different doses of UVA1 are used (Dawe 2003). Krutmann in his first studies used the high dose of 130 J/cm2; we prefer a medium dose (50–60 J/cm2) which is more efficacious than the low dose (10–20 J/cm2) and is tolerated well (Kowalzick et al. 1995; Schmidt et al. 1998).

Apart from atopic eczema, UVA1 is also used in localized scleroderma and granuloma anulare (Rombold et al. 2008). UVA1 has shown an inhibitory effect on mediator-secreting cells such as histamine from basophils or mast cells (Krönauer et al. 2003).

In our own study on 230 patients treated with low-dose, medium-dose, and high-dose UVA1 over 6 years, we could prove the good therapeutic effects in atopic eczema, scleroderma, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, prurigo nodularis, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (Rombold et al. 2008). 84 % of 86 patients with atopic eczema showed moderate to marked improvement after 3 weeks of UVA1 radiation while low dose was considerably weaker (Kowalzick et al. 1995).

UVA1, besides anti-inflammatory effects, also seems to have specific antipruritic efficacy which is well accepted by the patients. We perform UVA1 treatment in a total of 15 sessions over 3 weeks with a slow increase of dose. UVA1 has its place in acute flares of eczema and is tolerated well (Von Kobyletzki et al. 1999).

5.6.4 Photochemotherapy

There is no doubt that the most effective type of UV therapy is, together with the use of photosensitizing substances, photochemotherapy, e.g., psoralens (with UVA, PUVA). However, this also is the treatment with most side effects; it should be preserved for severe cases and can be compared to systemic immunosuppression.

Systemic application of psoralens is nowadays used only rarely. The topical application in a bath (balneophotochemotherapy) or in a cream (cream PUVA) is now the method of choice (Krutmann and Hönigsmann 1997).

Psoralen is used in a concentration between 0.1 and 0.5 mg/l (methoxypsoralen 8-MOP) or 0.3 % meladinine in a lukewarm bath (32–35 °C over 20 min). Alternatively, psoralen can be incorporated in a cream (0.001 %) which is allowed to penetrate the skin over 30 min prior to UVA radiation. This method is preferably used in hand or foot eczema or in nummular variants.

5.6.5 Visible Light

New developments include the application of visible light, especially the spectrum of the blue light, sometimes called “light vaccine,” which has been studied in pilot studies (Krutmann and Hönigsmann 1997, von Stebut et al., in prep).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree