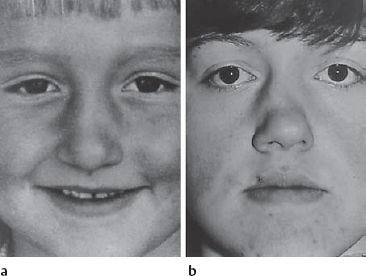

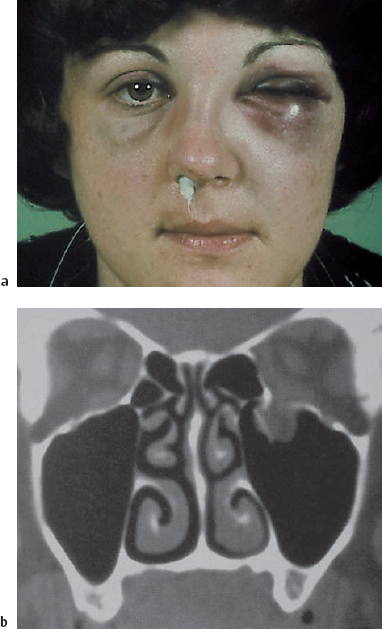

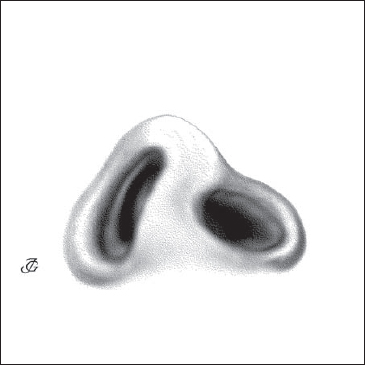

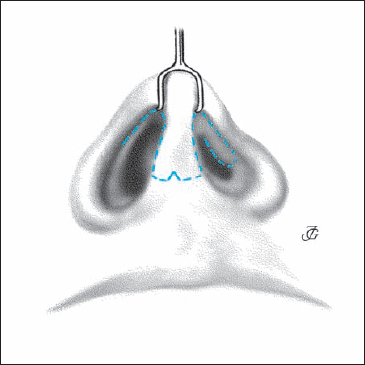

9 Special Subjects On the subject of nasal trauma, Hippocrates (460–377 BC) wrote in his book “Joints” that its treatment does not require any particular skill on the part of the doctor. Although his writings on how to treat fresh nasal injuries contain several recommendations that are still valid, he was certainly mistaken on this point. On the contrary, taking good care of a fresh nasal injury is a difficult art. Both correct diagnosis and adequate treatment require great skill. We know that most nasal deformities that we see in daily practice would not have occurred if the underlying trauma had been addressed correctly in the acute phase. Nasal injuries in childhood, if not properly treated, may have a great impact on later nasal form and function. A minor dislocation of the cartilaginous septum may lead to a septal deviation, crest, and spur during later nasal growth (Fig. 9.4a, b). A hematoma that has not been recognized and treated will cause scarring and retraction of the nasal dorsum, cartilaginous vault, and columella. A septal abscess in childhood, if not treated in its acute stage by reconstruction of the septal defect, will have grave consequences on growth of the midface and the nose (see Fig. 5.67a–d). We have the best chance to prevent these deformities if we see the patient when the injury is still fresh. Treatment at that time may prevent many of the functional and aesthetic problems that could arise in later life. Hippocrates on treating nasal fractures “For a simple fracture what is recommended is simple bandaging, so as to avoid the possible deformation caused by complicated bandages used to draw attention. When in addition to the fracture, the ridge of the nose is depressed or the nose is laterally dislocated, the recommended course of action includes reduction (which musttake place in the first few days), the placement of wads into the nostrils, and very careful bandaging. This applies for complicated fractures as well, since the injury is not considered an obstacle in performing the above.” Hippocrates (“Joints”). From: Apostolides 1997. Deviation of the nose and compression of the lobule are frequently observed in the newborn. About 30% of all newborns exhibit some flattening of the lobule immediately after birth. This flattening disappears quickly in most cases, though in some a deformity remains. Although individual cases of nasal deformity at birth were described long ago, the study of its incidence, causes, and treatment only started in the 1970s (e.g., Lindsay Gray, Jazbi, Jeppesen, Pirsig). In describing neonatal nasal deformities, we should distinguish between nasal deformities due to birth trauma and those occurring in utero. Nasal deformity in the newborn following vaginal birth is rather common. The incidence reported varies from 1%–23%. This variation is very likely due to differences in definition, time lapse between examination and birth, and ethnic factors. The majority of these deformities correct the mselves in a few days. The tissues are apparently flattened or pushed during birth, later returning to their original position due to their elasticity. In a minority of cases, however, the deviation remains and nasal breathing may be impaired (Jeppesen 1977, 3.2 %; Jazbi 1977, 1.9 %; Collo 1978, 1.6 %; Podoshin et al. 1991, 0.93 %; Hughes et al. 1999, 0.6 %). Concern about disturbed nasal growth is then justified. Nasal trauma due to vaginal birth is characterized by a deviation of the cartilaginous pyramid and lobule to one side and dislocation of the cartilaginous septum from its base to the opposite side. The columella is deviated, while the shape of the nostrils and alae is distorted and asymmetrical. Sometimes, bulging instead of a luxation of the anterior septum is found. Jeppesen and Windfield (1976) postulated that presentation of the child in left occipito-anterior position would lead to a luxation of the septal base to the right whereas presentation in right occipito-posterior position would cause a luxation to the left. Other authors (e.g. Kent et al. 1998) havenot been able to confirm this hypothesis, however. A proper diagnosis of these fresh birth trauma deformities is of paramount importance. The most important questions are: A septal dislocation is corrected as soon as possible. Steps In rare cases, a neonatal nasal deformity is observed that cannot be attributed to birth trauma, as the delivery is by cesarean section. The incidence is estimated at 0.5–1.0% or lower. Whether the condition is due to intrauterine trauma or hereditary factors is unclear. At examination, the external pyramid and septum are found to be deviating and immobile. Repositioning of the septum is impossible. Long-term follow up has shown that the deformity disappears spontaneously in about two-thirds of cases (Figs. 9.1a, b), whereas it remains in about one-third of the children (Pentz, Pirsig and Lenders, 1999). Nasal trauma is one of the most common injuries during childhood. No child reaches puberty without having suffered several minor and major falls and bumps on the nose. The majority of these accidents do not need special attention. However, some eventually lead to a nasal deformity. Fig. 9.1a Deviation of pyramid and septum in a neonate delivered by cesarean section; the septum appeared to be immobile. Fig. 9.1b Spontaneous correction of the deformity after 18 months. Fig. 9.2 Pronounced dorsal hematoma in a young child, which was evacuated through an IC incision. Fig. 9.3 Scarring of the ala and atrophy of the triangular cartilage on the left due to an untreated dorsal hematoma. Septal and pyramid deformities may gradually develop in later life when the septum becomes dislocated from its base by an accident with a frontolateral or basolateral impact. Even a minor trauma may have this effect. A frontal injury may cause a disruption of the cartilaginous pyramid from the bony pyramid. In these cases, sagging of the cartilaginous dorsum occurs. It is generally assumed that a high percentage of the nasal deformities in adults originate in minor injuries during childhood. Fig. 9.4a, b Untreated nasal injury with a slight deviation of the bony pyramid to the right in a 6-year-old girl(a). At age 17, a severe deformity had occurred (b). The external pyramid is underdeveloped (“child’s nose”); the maxilla shows retrusion; the bony pyramid deviates markedly to the right, while the cartilaginous pyramid deviates to the left (C-shape deformity). There is a severe saddling of the cartilaginous dorsum with a step at the junction between the cartilaginous and the bony pyramid (Pirsig 1992). Hematomas, especially septal and dorsal, should not be overlooked. In infants and children, septal hematomas occur rather frequently. They pose a major threat as they usually lead to a septal abscess and destruction of the septum. Soft-tissue lesions such as avulsion of the alae, columella, or the head of the inferior turbinate have to betreated as soon as possible. This also applies to dog and monkey bites and to lesions of the columella caused by intubation. The external nose, septum, and nasal cavity are inspected and palpated after mucosal decongestion in general or local anesthesia. Special attention is paid to the septum. A septal hematoma is to be excluded by palpating the septum with a cotton-wool applicator. Examining the nose in a child with a fresh injury puts quite a strain on the child, its parents, the doctor, and the hospital staff. Therefore, the appropriate intranasal inspection is often omitted. This may be acceptable in some cases, but in other cases such negligence may have grave consequences. Navigating in the gray area between doing too much and too little requires experience. Plain radiographs have almost no value in diagnosing fresh nasal injuries in children. CT scans may provide important information but cannot be performed routinely. Depending on the findings, we have to decide whether it is best to wait and see what happens or arrange for surgery. When we decide to follow a wait-and-see policy, the parents are asked to watch out for the following developments over the next days: Surgical treatment is indicated under the following circumstances: A septal hematoma should be opened and evacuated through a caudal septal incision (CSI). This is necessary to avoid necrosis of the septal cartilage and to prevent a septal abscess. A limited dorsal hematoma may be left alone. However, in children with a pronounced localized hematoma, the accumulated blood might be evacuated through a small intercartilaginous (IC) incision (Fig. 9.2). Internal dressings and external tapes are applied to prevent recurrence. If left untreated, large hematomas may lead to atrophy of the triangular cartilage and scarring of the soft tissues (Fig. 9.3). If the septum is dislocated, it is repositioned and fixed as required. Internal dressings are applied, and antibiotics are prescribed. If the septum is dislocated, it is reconstructed in the usual way through a CSI. The dislocated parts are mobilized and repositioned. Resections are avoided (see Chapter 5, p. 169 ff). A minor dislocation of the bony pyramid may be left untouched. We know, however, that a slight deviation or impression may become more pronounced in later years, especially during pubertal growth. Nevertheless, a wait-and-see policy is adopted in many cases, as septal-pyramid surgery can be performed later with less risk, if required. In children with more severe fractures of the nasal bones, one should not hesitate to operate in the acute stage (immediately or within 3–5 days). Usually, osteotomies are required to complete the fractures and allow repositioning of the dislocated parts. We know from follow-up studies that the results of surgery in the acute stage are often the best. Soft-tissue lesions are treated immediately (see text following). Nasal trauma is one of the most common injuries in adults. It is usually caused by sports, traffic accidents, and fights. Males are most frequently affected, especially young males between 15 and 25 years of age. A nasal trauma may be an isolated injury or part of a major maxillofacial and/or skull trauma. If it is part of a larger trauma, a completely different approach to diagnosis and treatment is required. Nasal injuries may involve the bony-cartilaginous skeleton, the soft tissues, or both. Depending on the impact of the trauma and the resulting fractures and dislocations, we may distinguish five types of trauma: those with a lateral, frontal, frontolateral, basal, or basolateral impact. In special circumstances, a combination of these main types may occur. This is one of the most common types of trauma. It may be inflicted by a fist during a fight, or by an elbow or knee in sports. The bony and/or cartilaginous pyramid and the septum are fractured. The bony and/or cartilaginous pyramid will deviate to the opposite side. The nasal bone on the side of the impact is impressed. The septum is usually fractured vertically or diagonally in its anterior part. Depending on the injury, the result may be a deviated bony and cartilaginous pyramid, a C-shaped or reversed C-shaped pyramid, or a deviated cartilaginous pyramid (Figs. 9.5a). See also Chapter 2, page 57, 58. This is another very frequent type of trauma. It is usually caused by a traffic accident, fall, or sport injury. The bony and/or cartilaginous pyramid will be impressed. The dorsal skin may be lacerated. In patients who received a severe impact on the bony bridge, the result may be a bony saddle nose with multiple fracturing of the nasal bones, skin lesions, and a septal fracture. In cases where the force has hit the cartilaginous pyramid, the triangular cartilages may be disconnected from the bony pyramid, resulting in a saddling nose and a vertical septal fracture. Lobular soft-tissue injuries may also occur (e.g., of the ala and the head of the inferior turbinate). Some injuries are caused by both lateral and frontal forces. Usually, one of the deformities previously described will result. This is another common type of trauma. It is caused by a fist blow, traffic accident or sport injury, or fall. The most common sequelae are a horizontal fracture of cartilaginous septum and soft-tissue lesions such as avulsion of the columella, alae, and the head of the inferior turbinate. It is not as simple to make the correct diagnosis in fresh nasal injuries as is usually thought. Edema, hematoma, bleeding, pain, and anxiety of the patient make it difficult to determine precisely what has been fractured, dislocated, or bruised. For a correct diagnosis of the nasal injury, we first need to obtain a full history of the cause and the angle of impact. Furthermore, information is needed about preexisting nasal complaints and deformities, previous surgery, and earlier injuries. The bony and cartilaginous pyramid, the lobule, and the internal nasal cavity are carefully inspected, palpated, and examined for any abnormal mobility. This is done after decongestion and anesthesia of the mucosal membranes. In patients with a fracture of the bony pyramid, local anesthesia of the bony pyramid by paranasal infiltration of lidocaine–adrenaline may be added (for techniques, see Chapter 3, p. 118 ff). In some cases, sedation prior to examination (and subsequent) treatment may be of great help. The diagnostic value of plain radiographs is limited. A negative outcome does not exclude a fracture, especially not at young age. They may be helpful, however, when swelling interferes with a reliable palpatory diagnosis. They may also help to diagnose an orbital blow-out fracture, as well as fractures of the maxilla and frontal sinus (Fig. 9.5b). In addition, they may be important for legal reasons. CT scans are performed in patients with a maxillofacial and skull trauma. In special cases, scans are performed to examine in detail the relationships between the cartilaginous and the bony pyramid. Color photographs of the nose and face are required for documentation. They are particularly important in legal cases when another party is involved. Depending on the type and severity of the trauma and the general condition of the patient, we may have to arrange for an ophthalmologic, maxillofacial, and neurological examination. First of all, treatment depends on whether we are dealing with an isolated nasal injury or with an injury as part of a major maxillofacial and/or skull trauma. Primary general care to secure the airways, bleeding, and circulation is provided first. The airway is secured by intubation or tracheotomy; bleeding is controlled as much as possible by anterior nasal tamponade or anterior and posterior nasal tamponade (Bellocq type); and circulation is assured. If the nasal injury is part of a major accident, reconstruction of the nasal septum and external pyramid is usually the last phase of surgical treatment. Surgery of the anterior skull base, repositioning and fixation of maxillofacial fractures, and orbital surgery should always precede nasal reconstruction. There is no doubt that the best way to treat a fresh septal and pyramid fracture is by surgical repositioning and reconstruction. Nevertheless, “closed reduction” is more commonly practiced. It is less invasive and takes less time to perform. Those who defend closed reduction also argue that the results are not too bad and that most patients are satisfied with the outcome. Finally, if complaints remain or reoccur, functional and/or aesthetic surgery can always be performed later. All these arguments are certainly valid. However, they do not dispel the evidence that surgical reconstruction in the acute or semi-acute phase produces the best results. Thus the question is when to choose closed reduction and when to prefer surgical correction? As many factors are involved, this decision has to be made for each patient individually. Some of the factors to take into account are the extent and type of the injury, the cause of the trauma, the wishes of the patient, the skill of the surgeon, and the hospital facilities. Injuries that may be treated by a so-called closed reduction are uncomplicated septum–pyramid fractures. The following injuries require immediate surgical reconstruction: Injuries that may be treated conservatively by internal dressings, taping, and stents are limited hematomas and ecchymoses. The best timing for surgical treatment of nasal injuries is within hours after the injury. Skin lesions and avulsions are taken care of as soon as possible. A septal hematoma is evacuated the same day. Repositioning of septal and pyramid fractures is also performed the same day. When indicated, this may be postponed, however. It has often been stated that injuries to the septum and pyramid should be addressed either within hours or after 3–5 days when the post-traumatic edema has subsided. Although it is certainly true that surgery in swollen and hyperemic tissues is more difficult, there are, in our opinion, no strong arguments against performing surgery during the first days after the trauma. The majority of septal and pyramidal deformities could have been prevented by adequate treatment of the primary injury. For many surgeons, closed reduction is the preferred treatment in the majority of cases. The reason is that if the attempt proves unsuccessful, surgical correction can always follow at a later stage. In many cases, however, the effect of a closed reduction is limited for two main reasons. First of all, it is difficult and sometimes impossible to reposition the dislocated bones, as the traumatic fracture is usually incomplete. Secondly, it is impossible to redress the bony pyramid without repositioning the deviated or fractured septum. Steps Septal fractures and septal hematomas are addressed as described and illustrated in Chapter 5, page 175 ff. The septum is mobilized through a CSI using a twotunnel approach. A hematoma is aspirated. Fractured parts are mobilized and repositioned (if necessary after minimal resections) and then fixated. Fractures of the bony pyramid are repositioned after complete mobilization of the fractured parts. Traumatic fractures are almost always incomplete. The lateral wall of the bony pyramid may be impressed, but the bony vault is usually still attached to the frontal bone and the frontal nasal spine. Therefore, closed reduction usually has a limited effect. To allow repositioning of the fractured fragments, the incomplete fractures have to be completed by osteotomies. It should be kept in mind that repositioning the external pyramid also requires mobilization of the septum. Disruption of the cartilaginous vault is corrected by taking the following steps:1) mobilizing and exorotating the septum; 2) performing osteotomies; and 3) repositioning and fixating the septolateral cartilage in its original position with guide sutures, fixating sutures, and splints. Avulsions of the columella or alae are closed in four layers: 1) vestibular skin; 2) connective-tissue layer;3) subcutis; and 4) external skin. Lesions of the head of the inferior turbinate may be closed by one or two resorbable sutures. In most cases, adjusting the tissues with Merocel, gelfoam, or a dressing with ointment usually suffices. In some cases with severe nasofacial trauma, the nose may have to be completely rebuilt. Steps Nasal surgery in children differs from that in adults; neither the indications nor the surgical techniques are the same. The root cause of this difference is that surgery influences further growth of the nose and the midface. The effects of surgery may be similar to those of other injuries. This applies in particular to surgery of the septum and the triangular cartilages (in other words, the septolateral cartilage) and to a lesser extent to surgery of the bony pyramid. This has become evident in many ways. First, it was reported in follow-up studies in children following submucous septal resection (Ombrédanne 1942). In later years, it was convincingly shown by various studies on identical twins (Huizing 1966, Pirsig 1992, Grymer 1997). Finally, it was systematically investigated in a large number of animal studies (Sarnat and Wechsler, Verwoerd and collaborators). The conclusions drawn from the information gathered so far may be summarized as follows: Immediate action is required. The hematoma (abscess) is drained through a CSI. The septum is explored; any defect is immediately reconstructed by transplantation of bone or cartilage to avoid dorsal saddling and columellar retraction. Internal dressings are applied, and antibiotics are administered systemically (see Chapter 5, p. 175 ff). This type of fracture is corrected within a few days. The dislocated parts are dissected, repositioned, and fixed in the midline. Resections are avoided as much as possible, (see p. 171 ff). When large, these are immediately drained via an IC incision. A supporting internal dressing and external taping is applied (see p. 301). The cartilage is repaired, readjusted in its position, and fixed to the septum and the bony pyramid. Whether and when surgery is performed is extensively discussed in the section on septal surgery in children (see Chapter 5, p. 171 ff). Minor deviations are not corrected before puberty. Major deformities and asymmetries may be corrected by osteotomies after mobilizing and repositioning the septum. Humps are left untouched unless they are very pronounced and cause severe psychological problems. Saddling is preferably corrected after puberty. However, in some patients with a pronounced congenital nasal and septal hypoplasia or a severe traumatic saddle nose, the septum may be reconstructed and the dorsum augmented at an earlier age. Usually, this is done for psychological and aesthetic reasons. The patient and his or her parents must be informed that a second and sometimes a third surgical procedure may be needed later. The best results are obtained after puberty. Lobular surgery should therefore be postponed when possible. In children with a pronounced congenital or acquired deformity (e.g., bifid nose, defect due to a bite or injury), the first stage of a multi-stage operation may be carried out earlier. The present status of nasal surgery in childhood can be summarized as follows: In cleft-lip patients, all nasal elements and adjacent structures are more or less affected. The bony and cartilaginous pyramid are asymmetrical and lean slightly to the noncleft side (NCS). The piriform aperture is asymmetrical, the aperture on the cleft side (CS) being lower and narrower. The anterior nasal spine deviates to the CS or may be missing. The premaxilla is severely deviated to the CS. The lobule is strongly asymmetrical. The tip is bifid and flat. The dome and lateral crus of the lobular cartilage on the CS are severely depressed, less convex, and more caudally located; the ala is elongated, flat, and displaced in a lateral and caudal direction; and the vestibule is narrow, with a more horizontal axis. The columella is short, broad, and oblique. Its upper end leans to the CS, its base retracted. The medial crus on the CS is somewhat displaced in a caudal direction (Fig. 9.6). The septum is severely deformed. Its caudal end is dislocated to the NCS and may thereby narrow the vestibule on this side. More posteriorly, the cartilaginous septum, vomer, and perpendicular plate are strongly deviated to the CS, obstructing the valve area and the nasal cavity. At the chondropremaxillary and perpendicular–vomeral junction, a pronounced cartilaginous and bony crest is present. The depressed ala usually contributes to the stenosis of the valve area. The inferior turbinate on the CS is lower and compressed in a lateral direction. Its bony lamella is lower than normal. On the NCS, the inferior turbinate is usually compensatory hypertrophied. The middle turbinate on the CS is generally somewhat more slender than on the NCS. For further details, see Chapter 2 (Figs. 2.18a–f). Rehabilitation of cleft-lip patients requires close cooperation between a number of specialists. Nowadays, all large medical centers have a so-called “Schizis team.” In such a team specialists of the following disciplines work together: plastic surgery, maxillofacial surgery, otorhinolaryngology, orthodontics, and speech therapy. Usually, a general pediatrician completes the team. Most teams treat a cleft-lip patient according to a general, accepted schedule. Such a schedule usually consists of three major phases of rehabilitation: a primary phase which is carried out within the first year of life, a secondary phase which is performed between age 4 and 10 years, and a final phase which is completed after puberty (Table 9.1). In recent years, some of the earlier insights about the time schedule of rehabilitation have changed, however. Nowadays, there is a tendency to correct the skeletal deformities of the hard palate and the septum at a younger age than before. Closure of the periosteum of the bony palate and the nasal floor at an early age may limit the severity of some of the anomalies, for instance those of the maxillary and premaxillary bones. Despite the importance of adopting a general treatment schedule in cleft-lip rehabilitation, treatment of cleft-lip deformities must be tailored to the patient’s needs and particular deformities. In this chapter we only deal with the rhinological aspects of rehabilitation of cleft-lip patients. Here, we discuss only the specific surgery of the septum, pyramid, and lobule in these cases. As to the surgery of the lip, maxilla, and palate as well as the various orthodontic options, we refer the reader to other textbooks. Until recently it was general policy to wait with septal surgery until after puberty. However, the development of more conservative techniques has allowed intervention at an earlier age, if indicated. Repositioning of the septum at childhood age may first of all have a beneficial effect on nasal breathing. Furthermore, it may limit to a certain extent further deformity of the septum and pyramid during growth. Whether or not (a first phase of) septal surgery is performed before puberty depends on several factors, in particular the quality of nasal breathing. As to the techniques of septal surgery, we refer to Chapter 5 (p. 140 ff). Surgery of the bony and cartilaginous pyramid is postponed until after puberty almost without exception. Deformity of the bony pyramid does not need early redressment. Pyramid surgery is usually performed in combination with secondary septal surgery (and anterior turbinoplasty) as required in the final phase of rehabilitation (Table 9.1). In patients with a limited septal and pyramid deformity it may be performed as part of the correction of the lobule. In most cases, however, septal and pyramid surgery is carried out first, while lobular surgery is done as one of the last steps some 12 months later. As to techniques we refer to Chapter 6, page 192 ff. Lobular surgery is always performed in the final phase of rehabilitation. Usually the lobule is reconstructed in a separate procedure 1 year after correction of the septum and the bony pyramid. Reconstructing the nasal lobule in cleft-lip patients is one of the most difficult surgical procedures in nasal surgery, requiring great skill and experience. Several techniques have been developed. Over the last decades, Tajima (1977), Millard (1982), Gubisch (1990), and Farrior (1993), among others, have made important contributions. Here, we limit ourselves to a description of the method used by Rettinger (Rettinger and O’Connel 2001). This technique comprises the following main phases: Steps Fig. 9.6 Characteristic deformity of the lobule in a patient with a cleft lip on the left side.

Acute Nasal Trauma

Nasal Trauma In the Newborn

Nasal Trauma In the Newborn

Nasal Deformity Due to Birth Trauma

Diagnosis

Treatment

Deformities Occurring In Utero

Acute Nasal Trauma In Childhood

Acute Nasal Trauma In Childhood

Pathology

Diagnosis

Treatment

Wait-and-See Policy

Surgical Treatment

Acute Nasal Trauma In Adults

Acute Nasal Trauma In Adults

Pathology

Fractures and Dislocation of the Bony and Cartilaginous Skeleton

Lateral Impact Trauma

Frontal Impact Trauma

Frontolateral Impact Trauma

Basal and Basolateral Impact Trauma

Diagnosis

History

Examination

Plain Radiographs and CT scans

Color Photographs

Consultation

Treatment

Closed Reduction or Surgical Reconstruction?

Immediate Surgical Reconstruction

Conservative Treatment

Optimal Time For Surgery

Technique of Closed Reduction

Technique of Repositioning and Reconstruction

Technique of Rebuilding a Severely Damaged Nose

Nasal Surgery In Children

General

General

Clinical and Experimental Evidence

Clinical and Experimental Evidence

When Should Surgery Be Performed?

When Should Surgery Be Performed?

Fresh Injuries

Long-Standing Deformities

Conclusions

Conclusions

Nasal Surgery In the Unilateral Cleft-Lip Nose

Pathology

Pathology

Treatment

Treatment

Rehabilitation Schedule

Surgical Techniques

Surgical Techniques

Septal Surgery

Pyramid Surgery

Lobular Surgery

Phase 1 | |

2–4 m | • closure of lip, alveolus, maxilla, and hard palate |

12 m | • closure of posterior velum |

Phase 2 | |

4–5 y | • speech therapy, velopharyngoplasty |

5–6 y | • correction of lip/elongation of lip in bilateral clefts |

• vestibulum oris plasty | |

8–10 y | • septal surgery, first phase |

• orthodontic treatment | |

Phase 3 | |

16–18 y | • septorhinoplasty, first septal-pyramid surgery, |

• 12 m later lobular surgery | |

• orthodontic surgery/prosthesis |

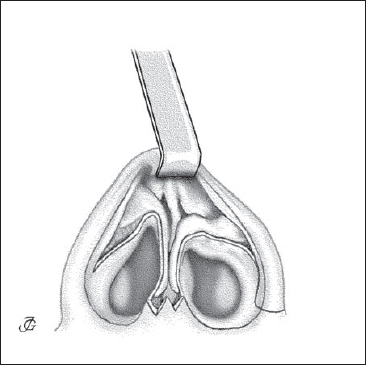

Fig. 9.7b The lobular cartilages, anterior septum, and cartilaginous dorsum are completely exposed. On the CS the vestibular skin remains attached to the cartilage.

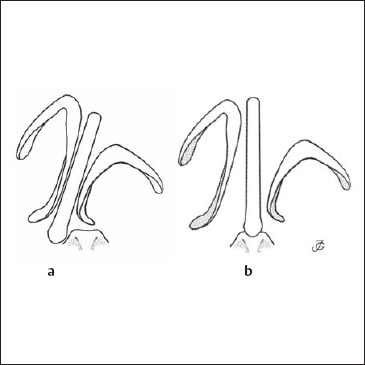

Fig. 9.8a, b The anterior septum is corrected and fixed in the midline.

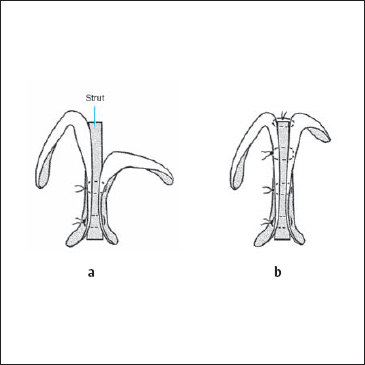

- The medial crura are reinforced by a rectangular strut taken from the posterior part of the septum to increase lobular projection and lower the columellar base, using 5–0 slowly resorbable suture material. On the CS, the medial crus is therefore fixed in a somewhat higher position to raise the dome slightly (Fig. 9.9a, b).

- The dome and lateral crus with the vestibular skin attached on the CS are redraped in an upward and medial direction. The two domes are sutured together at the same level by at least two interdomal 5–0 slowly resorbable sutures. Special care is taken to leave a distance of about 1–2 mm between the domes (Fig. 9.9b).

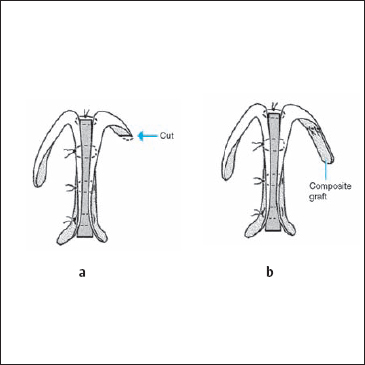

- Due to medialization of the lateral crus with vestibular skin, there is now a lack of cartilage and skin at the lateral wall of the vestibule. This degect is repaired with a composite graft taken from the auricle. The graft is sculpted as required and sutured in place with 5–0 resorbable sutures(Figs. 9.10a, b)

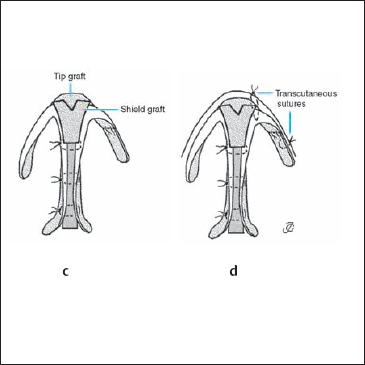

- A shield and/or tip graft may be applied to give the tip more projection and definition (Fig. 9.10c).

- To fix the dome and lateral crus on the CS in their new position, two transcutaneous sutures are applied (Fig. 9.10d).

Fig. 9.10a, b

a The edge of the lateral crus is resected.

b The resulting defect at the lateral wall of the vestibule is reconstructed with a composite graft taken from the auricle.

Fig. 9.10c, d

c A shield (and/or tip) may be applied to give the tip more projection and definition.

d To fix the dome and lateral crus on the CS in their new position, two transcutaneous sutures may be used.

The Nose and Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders

The medical profession has long ignored sleep-related breathing disorders and snoring, which were perceived as a social rather than a medical issue. In the late 1970s and the 1980s, however, greater interest was shown in disorders of sleep and snoring. Surgery of the soft palate and pharynx (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty) was introduced by Ikematsu (1964), followed by Fujita (1981), and further developed by others. Nasal masks for positive-pressure ventilation were developed to avoid pharyngeal collapse during sleep (Sullivan et al. 1981). A new subspecialty called “rhonchology” appeared. More recently, an effort has been made to start classifying and standardizing symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment.

Types of Obstructive Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders

Types of Obstructive Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders

Nowadays, three different types of sleep-related breathing disorders are distinguished: primary or nonapneic snoring; upper airway resistance syndrome (URAS); and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

- Primary or nonapneic snoring (previously called “benign snoring,” “social snoring,” or “habitual snoring”) is a relatively harmless condition. The intensity of snoring is less than 70 dB, and apnea is absent or rare.

- URAS is characterized by chronic daytime sleepiness in the absence of distinct apneas/hypopneas. A higher upper-airway resistance, which is recognized by oesophageal pressure measurement, causes respiratory arousals and sleep fragmentation.

- OSA is characterized by episodes of partial or complete obstruction of the upper airways leading to snoring and episodes of apnea with a minimum duration of 10 seconds and oxygen desaturation. It is mostly associated with daytime fatigue and may cause cardiopulmonary and neurological disorders.

The borderlines between these three types are still rather vague. Changes in definitions and terminology may therefore be expected in the near future.

Pathology and Causative Factors

Pathology and Causative Factors

Snoring noises are produced at the level of the pharynx. Apneas are caused by temporary collapse of a pharyngeal segment. A major causative role is played by the dimensions of the nasopharynx, palate, oropharynx, tongue base, and hypopharynx. Other important factors are the condition of the soft tissues, in particular of the mucosa, the musculature of these areas, and the size of the tonsils. Secondary causative factors are obesity, alcohol intake, use of certain medications, and sleeping position. Impaired nasal breathing may play a role, but recent studies have demonstrated that this factor is less important than previously thought.

The Role of the Nose In Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders

In former decades, obstruction of nasal breathing was widely believed to be one of the main causes of snoring. Patients were sent to the ENT surgeon to have their septum straightened or their nasal polyps removed. The restoration of nasal breathing turned out to have considerably less effect on snoring than expected, however. In some cases, complaints of snoring and apnea have even been found to increase after improving nasal breathing. Unfortunately, we do not yet have methods to predict the effects of nasal surgery on snoring in an individual case. Nevertheless, it is advisable to treat nasal obstruction in patients suffering from snoring and apneas. In cases with allergic rhinitis, antiallergic treatment is given. In patients with polyposis or septal-pyramid deformities, surgery is performed. This is done primarily because most patients report a (considerable) improvement in their quality of life after improvement of nasal breathing. Secondly, nasal surgery can reduce pressure in nasal positive pressure ventilation treatment and thus increase the compliance to use nasal positive pressure ventilation.

In general, snoring is decreased or abolished in only 25% of patients when normal nasal breathing is restored. In OSA patients, this figure is even lower, lying between 15% and 20%. Generally speaking, any treatment will be successful if it leads to enlargement of the pharyngeal lumen.

Treatment

Treatment

Modalities

In brief, the main options are:

- Weight loss, change in life style, and change in sleeping position.

- Nasal continuous positive pressure ventilation (nCPAP).

- Internal and external nasal dilatators.

- Progenic oral devices.

- Nasal surgery in cases with obstructed nasal breathing.

- Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty with or without tonsillectomy (or other types of velar surgery such as laser-assisted uvuloplasty (LAUP).

- Pharyngeal and tongue-base surgery.

- Maxillomandibular advancement surgery.

- Tracheotomy.

Nasal Surgery

In patients with impaired nasal breathing, surgery (or conservative treatment) must always be considered. However, the main reason for nasal surgery should be diminishing nasal complaints. Only in a limited number of patients has a beneficial effect on snoring and apneas been reported. This applies particularly to OSA patients (e.g., Pirsig and Verse 2000).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree