Chapter 37 Skin signs of gastrointestinal disease

| Jaundice | Purpura |

| Pigment changes | Loss of body hair |

| Spider angioma | Gynecomastia |

| Palmar erythema | Peripheral edema |

| Dilated abdominal wall veins | Non-palpable gallbladder |

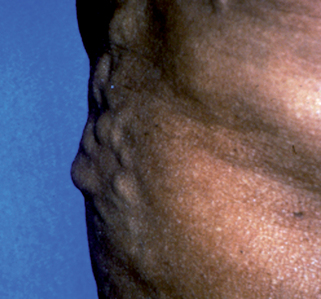

Portal venous hypertension due to chronic liver disease leads to the development of collateral circulation, with esophageal varices as an example. In the skin, this is observed as dilation of the abdominal wall veins (Fig. 37-1). Caput medusa refers to the dilated periumbilical veins and has been known for centuries as a marker of advanced liver disease. In men with chronic liver disease, induction of a “hyperestrogen state” (due to a decreased efficacy of estrogen breakdown in the liver) leads to gynecomastia, testicular atrophy; loss of axillary, truncal, and pubic hair; and a female pattern of pubic hair. Purpura, ecchymoses, and gingival bleeding reflect impaired hepatic production of various clotting factors, especially the vitamin K–dependent factors. Peripheral edema and ascites indicate hypoalbuminemia and/or portal venous hypertension.

Table 37-1. Conditions Associated with GI Bleeding and Skin Lesions

| INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS | VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS AND TUMORS |

|---|---|

| Ulcerative colitis Crohn’s disease Henoch-Schönlein purpura Polyarteritis nodosa | Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu) Kaposi’s sarcoma Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome |

| HEREDITARY POLYPOSIS SYNDROMES | MISCELLANEOUS |

| Gardner’s syndrome Peutz-Jeghers syndrome Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden’s syndrome) | Ehlers-Danlos syndrome Pseudoxanthoma elastica |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree