CHAPTER 19 Skin-Colored and Red Papules and Nodules

SKIN-COLORED PAPULES AND PLAQUES

When the term “skin-colored” is applied to a lesion it reflects the color of the patient’s normal skin. Thus, a brown lesion on a darkly pigmented individual would still be considered as a skin-colored process. Likewise, an erythematous lesion on a normally pink to red mucosal surface would also be a skin-colored lesion. Skin-colored papules and plaques may be smooth or rough-surfaced. Roughness to palpation implies the presence of scale even when such is not visible to the naked eye.

Genital warts (human papillomavirus infection)

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Genital warts are caused by nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA-containing human papillomaviruses (HPV). The incidence of HPV infection has risen very rapidly in the United Kingdom and somewhat less rapidly in the United States1. The estimated lifetime incidence of visible genital warts in women is about 4%2. The annual incidence of genital warts in the United States, based on private office visit reports, is somewhat less than 1%1. These data reflect only clinically apparent HPV infections. It is estimated that the prevalence of clinically inapparent external genital infections is about 13% in women of all ages and about 22% in 20-year-old women3. Moreover, the cumulative incidence in young sexually active women over a 2–3-year period is greater than 40%3. Prevalence declines fairly rapidly with age, falling to about 10% by age 353. These figures are similar to those reported for HPV infection of the cervix4. Taken together, these data suggest that HPV is the most common of all sexually transmitted infections.

From a standpoint of clinical morphology there are four major types of genital warts. Keratotic (common-type) warts are similar to those that occur on the hands and are “square” (5–10 mm in diameter and 5–10 mm in height). They have a rough, scaling surface, are skin-colored or slightly brown, and occur on the mons pubis, the upper inner thighs, and other dry regions of the anogenital area (Figure 19.1). Filiform (condylomata acuminata-type) warts are taller (10–20 mm) than they are wide (2–5 mm), are skin-colored or pink, have a “brush-like” filiform tip, and occur in the moist areas of the anogenital area. Flat-topped (papular) warts are wider (5–15 mm) than they are tall (2–5 mm), are smooth-surfaced, and occur anywhere in the anogenital region (Figures 19.2 and 19.3). Their color is highly variable: they may be skin-colored, pink, red, brown, or black (Figure 19.4). This type of wart may enlarge centrifugally or coalesce to form large plaques. Nodular (Buschke–Lowenstein-type) warts are spherical with a cerebriform or mammillated surface. They are skin-colored to pink and are usually smooth-surfaced (Figures 19.5 and 19.6).

Figure 19.1 Some genital warts show a verrucous, firm surface, as seen in this wart.

(Reproduced from P. J. Lynch and L. Edwards Genital Dermatology (Fig. 9-5), Churchill Livingstone.)

Figure 19.2 The term “condylomata acuminata” refers to genital warts such as these, which exhibit acuminata morphology.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for genital warts include vestibular papillomatosis, lymphangiectasia, skin tags, and molluscum contagiosum (Table 19.1). All of these are recognizable clinically. Vestibular papillomatosis consists of closely set, uniform-appearing, small, rounded papules occurring in a cobblestone-like pattern. This normal anatomic variant is only found in the vulvar vestibule. Skin tags are pedunculated, soft on palpation, smooth-surfaced, and primarily located on hair-bearing skin. Molluscum contagiosum are skin-colored to white, hemispherical, often umbilicated papules; they are also located primarily on hair-bearing skin.

Table 19.1 Genital Warts (Human Papillomavirus Infection)

| Diagnosis |

| Four types of lesions; most are skin-colored and rough surfaced: |

| 1. Keratotic (square shape) |

| 2. Filiform (taller than wide) |

| 3. Flat-topped (wider than tall) |

| 4. Nodular (spherical) |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| Vestibular papillomatosis |

| Molluscum contagiosum |

| Lymphangiectasia |

| Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia |

| Therapy |

| Medical therapy |

| Podofilox |

| Imiquimod |

| Podophyllin |

| Bi- or trichloroacetic acid |

| Procedural therapy |

| Cryotherapy |

| Excision |

| Electrosurgery |

| Laser ablation |

Histology and laboratory tests

Tests to identify specific HPV types are commercially available5. Proponents of such testing state that identification of high-risk HPV types gives useful prognostic information. However, these tests are expensive and limited in scope. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) do not recommend the use of DNA testing to determine the HPV type6. HPV cannot be cultured and therefore the only laboratory approach available to identify and type these viruses requires use of primer-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of viral DNA.

Pathogenesis

Genital warts are caused by HPV. These DNA viruses are very small and only contain approximately 8000 base pairs. The DNA is double-stranded and found in the form of a closed circle. HPV DNA is enclosed in an icosahedral protein capsid. Nucleotide sequence is highly variable, resulting in the evolutionary development of more than 100 HPV types. Genital infections are caused by about 30 or 40 of these types. The genital HPV types are divided into two groups of low- and high-risk viruses based on the predilection to cause epithelial cancers. The most important members of the low-risk group are HPV 6 and 11. These two types account for more than 90% of external genital warts1. The most important members of the high-risk group are HPV 16 and 18. They account for about 70% of cervical carcinomas7 and an even higher proportion of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. A dozen or more additional HPV types account for the remainder of HPV-related malignancies7.

Although DNA for the genital HPV types can be identified by PCR on fingers and inanimate objects such as specula, underwear, and laser plumes, epidemiological studies suggest that almost all genital infections in adults are spread by sexual contact1. The average incubation period from the time of acquisition to the development of visible warts ranges from several weeks to several months. Not surprisingly, other concomitant sexually transmitted diseases are found in about 15% of patients with genital warts8. Studies suggest that condom use might protect against the acquisition of genital warts9. The role played by viral load, hormones, smoking, and male circumcision in the acquisition of HPV infection is controversial3.

The situation in children with genital warts is somewhat different. Development as a result of sexual abuse certainly occurs but vertical transmission from an infected vaginal birth canal is quite common, as is horizontal, nonsexual, transmission (Figure 19.7). It is important to recognize that the mode of acquisition in children cannot be determined by the clinical appearance, the anatomic site, or the specific HPV type. A careful and thorough history for the possibility of sexual abuse should always be obtained even though positive evidence for abuse is found in only a minority of such cases10.

HPV can only infect epithelial cells. The virus enters the epithelium at the basal layer of the epidermis where initial replication occurs. Additional replication occurs in the suprabasal layers and, eventually, intact virions are shed from the surface as differentiated epithelial cells are sloughed into the environment. In benign infections, the HPV DNA remains in an episomal location and does not become incorporated into the host-cell DNA. The mechanism through which HPV infection results in the development of malignancy is discussed in Chapter 23.

Therapy and prognosis

Untreated genital warts tend to resolve with the passage of time. Unfortunately, there are few published data indicating the percentage and rate of resolution. Information regarding the resolution of cervical HPV infections is much better and this information will be used as a surrogate for external genital infection. As demonstrated by the marked fall-off in prevalence rates with age, most untreated cervical HPV infections are transient, with approximately 90% resolving within 2 or 3 years11. Infections with low-risk HPV types appear to be cleared more rapidly than those due to high-risk HPV types3,11. Clearance is primarily due to the development of immune reactivity. Innate immune response and humoral immunity presumably play some role but it is cell-mediated immune response that is critical to resolution11. Following clearance, reinfection with the same, or a different, type of HPV is possible.

Immunosuppressed individuals, especially those who are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive, tend to have infections that persist for many years. Women with persistent infections due to high-risk HPV types (mostly HPV 16 and 18) are at increased risk for the development of cervical and vulvar squamous cell carcinoma11.

In terms of treatment, it is pertinent to ask three questions. First, should sexual partners be examined? The answer is probably no. Acquisition of an asymptomatic infection may have occurred years ago and contact tracing just would not be feasible. And, the contact person may have had latent infection, in which case clinical recognition of the infected partner would not be possible. Second, should genital warts be biopsied? The answer is sometimes. Filiform and small nodular warts are unlikely to show dysplasia and need not be biopsied. Larger nodular warts (Buschke–Lowenstein-type) and flat-topped warts of any color have a higher risk of dysplasia and therefore should be sampled. Third, should genital warts be typed? As indicated above, the high cost coupled with the poor sensitivity and specificity of these tests has led the CDC to recommend that typing not be performed6.

The CDC discusses the treatment of genital warts in its revised treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted disease6. Two statements from this document are worth quoting: “Existing data indicate that currently available therapies for genital warts might reduce, but probably do not eradicate, HPV infectivity. Whether the reduction in HPV viral DNA resulting from treatment impacts future transmission remains unclear” and “No definitive evidence suggests that any of the available treatments are superior to any other and no single treatment is ideal for all patients or all warts”6. In addition to the CDC guidelines, there have been two thorough recent reviews of therapy for genital warts.12,13 Much of what follows is based on the information from these sources.

Office-based destructive therapy

The application of cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen using either a cotton-tipped applicator or a cryospray container is probably the most widely used therapy for genital warts. It is generally carried out every other week. It is moderately painful but local anesthetics are not required. Scarring occurs only rarely. Cure rates of 70–80% are possible after three to four treatments but recurrence rates are quite high. Alternatively, genital warts can be removed by scalpel or scissors excision or they can be destroyed by electrosurgery or carbon dioxide laser ablation. All four of these approaches require the use of a local anesthetic and all may lead to prolonged healing and, potentially, some scarring. The advantage of this approach is that all, or nearly all, of the warts can be destroyed or removed in a single office visit. Unfortunately, recurrence rates are about 25%.

Vaccines

The Food and Drug Administration has recently approved a quadrivalent vaccine for women 9–26 years of age. This vaccine is directed against HPV 6 and 11 (the two types most often associated with genital warts) and HPV 16 and 18 (the two types most often associated with cervical and vulvar carcinoma)14. The impressive results in clinical trials demonstrated that there was a dramatic reduction in the prevention of new infection and some clearance of existing infection. As might be expected, additional information suggests that this vaccine also has high efficacy for the prevention of HPV 16- and 18-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN 2 and 3)15. Although this vaccine therapy is probably the most exciting advance ever made for the prevention and therapy of HPV infection, enthusiasm must be tempered by the high cost, unknown duration of effectiveness, and likely resistance to its use by individuals in some groups. A second vaccine, directed only towards HPV 16 and 18, is in development16.

Molluscum contagiosum

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Most studies suggest that about 80–90% of all molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV) infections occur in children17,18. However, over the last 30 years there has been an increased incidence in adults, occurring as a result of sexual transmission. The annual incidence of clinically evident molluscum contagiosum is probably around 1–2% in the western world19. Asymptomatic infection must occur with even greater frequency as antibodies to MCV are found in 6–23% of the normal population20,21. The proportion of the population with such antibodies rises with age and may reach 40% by mid-adult life21. Individuals with depressed cell-mediated immunity (especially untreated patients with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)) are at greater risk of developing molluscum contagiosum22. There may also be an increased risk of MCV infection in those with atopic dermatitis and those who are applying topical steroids or tacrolimus on a regular basis18.

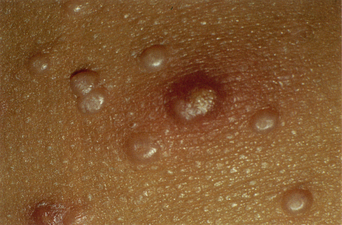

The clinical lesions of molluscum contagiosum are smooth-surfaced hemispherical papules averaging 3–10 mm in diameter. These papules are usually skin-colored but they may also be white, pink, or translucent (Figures 19.8 and 19.9). Central umbilication, a highly characteristic feature, is found in about 30–50% of larger lesions but is generally absent in new, small lesions (Figures 19.10 and 19.11). Rarely, giant lesions (up to 2 cm in diameter) develop. Sometimes as a result of trauma, or in the immunologically mediated resolution phase, a molluscum lesion and the perilesional skin become bright red and tender (Figure 19.12). Such lesions simulate furuncles and inflamed cysts.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree