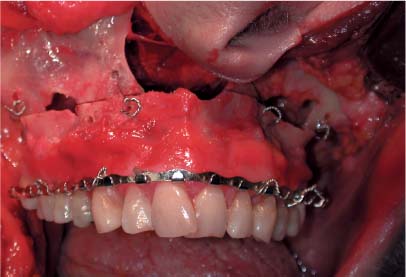

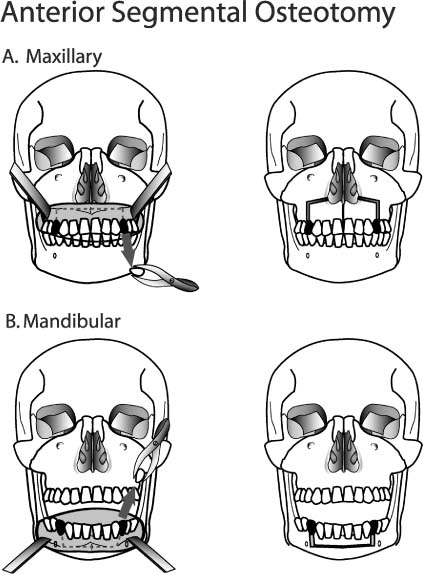

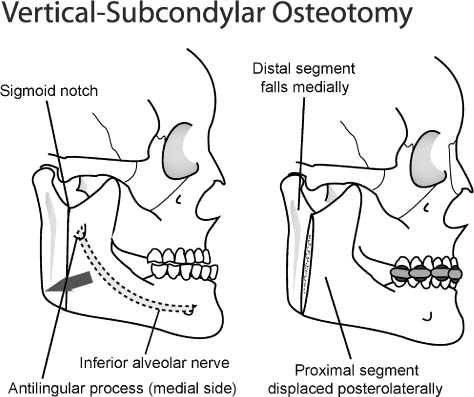

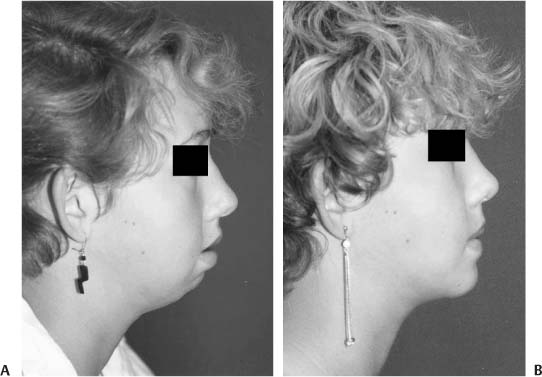

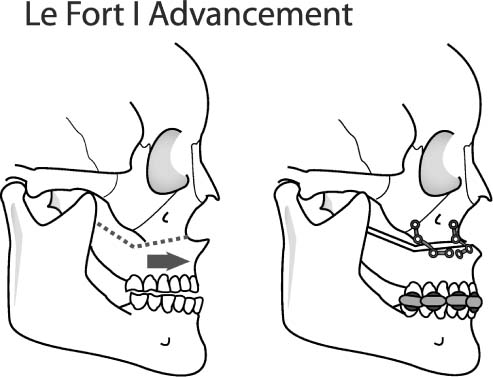

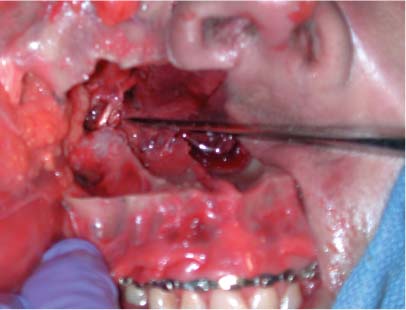

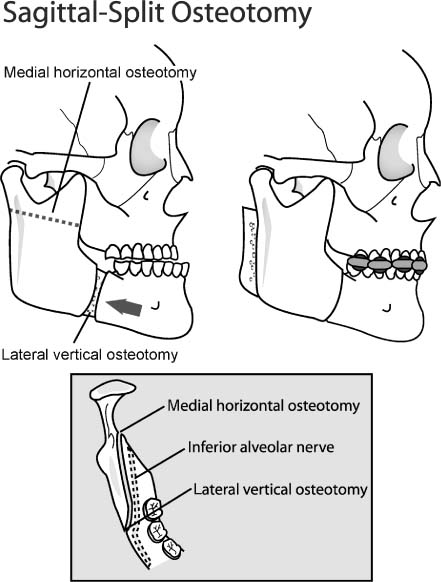

12 The ideals of beauty are not always consistent across cultural divides. This truism is well exemplified by the unique skeletal-reduction surgeries that are fashionable in Asia. For instance, malar convexity that is a hallmark of Western allure is oftentimes considered an unattractive attribute for the Asian face. Despite the deluge of periodicals, posters, and other media that extol Western beauty, a fundamental desire to maintain one’s distinct ethnicity informs many a decision to undergo cosmetic surgery. This trend has become increasingly evident over the past decade. However, certain Asian skeletal features, for example, relatively lower facial convexity, are deemed universally unaesthetic and transcend these peculiar cultural differences. The Western surgeon should always be cognizant of and sensitive toward these distinctive cultural and anatomic traits. Before a careful review of surgical options for skeletal modification can be embarked upon, the reader should understand the particular skeletal features that serve as the structural underpinning of the Asian face. The forehead and brow region exhibit a narrow expanse and flat contour, with a posterior inclination superiorly. The temple region may appear more hollowed due to the relative protuberance of the zygomatic arch. The orbits are shallower due to both a less recessed bony orbital cavity and a fuller eyelid. The midfacial skeleton is often hypoplastic and extends to the central aspect of the face (i.e., a less prominent nasal spine and a deficient premaxillary segment). The straight brow contour, the shallower orbit, and the hypoplastic midface all contribute to the overall flatter appearance of the upper and midface. However, the lower face is typically more convex due to several factors. The premaxillary deficiency is notable below the nose, but the bone tends to curve outward toward a prominent incisor show, which contributes to the perceived convexity. This bony configuration affects the overlying soft tissue with an acute nasolabial angle, potential labial incompetence, and “gummy” smile. This convexity is accentuated by the mandibular prognathism that often predominates in the Asian face. In addition, the inferior aspect of the chin tends to recede posteriorly, which further exacerbates the convex profile. The subject of skeletal surgery of the Asian face is broad and complex. The topic embraces diverse disciplines, including craniofacial surgery, facial plastic surgery, and oral and maxillofacial surgery. The focus of this chapter, as the title aptly declares, is confined to cosmetic facial endeavors. Reconstructive and orthognathic surgery procedures lie beyond the scope of the text. However, elective bony surgery that directly affects cosmesis will be included even if functional orthognathic proficiency is integral to the procedure. The reader is advised to undertake these more advanced surgical techniques after appropriate completion of formal training. The following discussion will be broadly classified according to advancement (augmentation) and reduction procedures. The former category is more familiar in the West in that maxillary, mandibular, and chin advancements are staple procedures for the oral and maxillofacial surgeon and at times the facial plastic surgeon. Accordingly, any analogous bony reductions that involve the same technique as the described advancement will be considered the same procedure and not be further elaborated upon in a separate section. Several bony reduction-type surgeries are unique to the Asian patient and include both malar and mandibular-angle resections. Figure 12-1 A Le Fort I advancement or recession can improve maxillary position and thereby correct occlusal disharmony and enhance cosmesis. The osteotomy is undertaken from the pyriform aperture back to the pterygomaxillary fissure bilaterally and more medially to separate the lateral nasal walls and septum from the maxilla and finally between the maxillary tuberosity and the pterygoid process. Although a Le Fort III osteotomy has been advocated for midfacial advancement, traditionally a Le Fort I osteotomy is a more popular option (Fig. 12-1). During the preoperative phase, the patient must be subjected to photographic, cephalometric, and occlusal analysis before embarking on the surgical enterprise. Precise preoperative dental models are used to plan the surgical procedure and to determine the degree of advancement or recession that should be undertaken. An occlusal wafer is fabricated based on these models that will serve as an intraoperative guide for alignment of the mobilized maxillary and mandibular segments. Figure 12-2 Cadaveric photograph shows the exposed greater palatine neurovascular bundle that must be carefully preserved during osteotomy. The lateral and medial osteotomies are executed with a reciprocating saw, whereas the final bony release near the neurovascular bundle should be judiciously undertaken with elevators and rongeurs. (Courtesy of Edward W. Chang, M.D., D.D.S.) Figure 12-3 Cadaveric photograph shows wire fixation placed prior to miniplate fixation to secure the maxilla in its new position. Erich arch bars are shown that would normally be secured to the mandible to set proper occlusion before placement of maxillary wire fixation, using the interim occlusal wafer as a guide. (Courtesy of Edward W. Chang, M.D., D.D.S.) Various combinations of osteotomies and bone grafting may be employed to achieve the optimal outcome. As the incidence of mandibular prognathism is relatively high in the Asian population, a combined mandibular setback and maxillary advancement may be accomplished for improved skeletal harmony. Pre-maxillary hypoplasia may be addressed with a Le Fort II advancement osteotomy. Alternatively, a Le Fort I osteotomy may be supplemented with a central pre-maxillary bone graft or alloplastic implantation, which may be preferred to the more morbid Le Fort II advancement. As alluded to in the opening portion of this chapter, maxillary setbacks will not be reiterated in a separate section, as the procedure mimics the described procedure except with retrograde displacement of the bony segment. However, it may be noted that posterior bony translocations may be unstable and less predictable. Rather than advance the entire maxillary complex via a Le Fort I osteotomy, an anterior segmental osteotomy may be undertaken to mobilize only the central, anterior dentoalveolar segment if that is the only bony region that merits repositioning. Bimaxillary protrusion (simianism) is characteristic of some Asians and may benefit from bimaxillary recession via combined maxillary and mandibular anterior segmental osteotomies (Fig. 12-4A-F). Rigid fixation of the mobilized maxillary and mandibular segments to their respective bony framework can facilitate an early return to social and professional life that would not be possible with traditional maxillomandibular wire fixation. Figure 12-4 (A-C) This 23-year-old Korean woman underwent bimaxillary anterior segmental osteotomy with 4 mm recession and 3 mm downward movement of her maxillary segment and with 4.2 mm recession and 3 mm impaction of her mandibular segment. (The vertical reorientation of the bony segments was undertaken to show more of her teeth during smiling.) She also underwent concurrent mandibular contouring surgery. (D-F) She is shown 6 months postoperatively. (Courtesy of Jung Soo Lee, M.D.) Mandibular anterior segmental osteotomy follows the same principles outlined above, but with the added attention that should be paid to avoid injury to the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN). The mandibular first premolars are extracted at the outset, and the two vertical mucoperiosteal incisions are made in the region of the extracted teeth. The horizontal incision is then made to join the vertical incisions below the dental roots. The osteotomy line is exposed, taking care not to injure the mental nerves. The oscillating saw is used to fashion the osteotomy cuts and to mobilize the anterior mandibular segment. The segment is repositioned to the desired position and guided into position with an occlusal wafer splint and fixed with miniplate and interdental wiring, as described above for maxillary anterior segmental osteotomy. Preoperative evaluation of mandibular position follows the prescribed analyses for maxillary surgery (i.e., cephalometric, photographic, and occlusal studies). An overprojected mandible may be retrodisplaced via two principal methods—vertical-subcondylar and sagittal-split osteotomies—the latter of which represents the more common surgical technique. For a retruded mandible, a sagittal-split osteotomy, sliding genioplasty (vide infra), and placement of an alloplastic implant are all viable methods for advancement depending on the presence of a malocclusion (sagittal-split technique) or absence thereof (sliding genioplasty or alloplastic insertion). Figure 12-5 (A,B) As an alternative to advancement or recession of the entire malar or mandibular complex, the central dentoalveolar segment can be mobilized to improve occlusion and aesthetic appearance with an anterior segmental osteotomy. As part of both a maxillary and mandibular anterior segmental osteotomy, the first premolar must be extracted to facilitate alignment. Vertical osteotomy cuts are made in the region of the extracted teeth and joined with a horizontal osteotomy that resides just beyond the dental apices. Mobilization of the bony maxillary segment is more involved compared with mandibular anterior segmental osteotomy, and the details are elaborated in the text. Removal of any bone that restricts movement of the mobilized segment is proportionately undertaken. The mobilized segment is guided into position with an interim occlusal splint and fixed with a combination of miniplates and interdental wiring. Intermaxillary (maxillomandibular) fixation is generally not required. The vertical-subcondylar technique (Fig. 12-6) for mandibular prognathism touts the major advantage of more infrequent inferior alveolar nerve injury than the sagittal-split method. The osteotomy may be approached either intraorally, which avoids an external incision and reduces marginal-mandibular nerve injury, or extraorally, which may be technically less demanding but may result in a conspicuous cutaneous scar. However, the greater obliquity of the mandibular rami in relation to the sagittal axis affords easier intraoral exposure. As mentioned, the sagittal-split technique (Fig. 12-7) offers the versatility of bidirectional mandibular repositioning (advancement or recession) (Fig. 12-8A,B). However, this technique suffers from three known potential complications: IAN injury (as high as a reported 45%), proximal-segment necrosis (a rare entity), and dental avulsion. Figure 12-6 The vertical-subcondylar method permits mandibular advancement or recession and is an alternative to the sagittal-split method. Osteotomies are fashioned from the sigmoid notch down to the mandibular angle behind the antilingular process to avoid IAN injury. Figure 12-7 The sagittal-split method permits mandibular advancement or recession and is an alternative to the vertical-subcondylar method. A horizontal osteotomy is commenced 5 mm superior to the lingula through the medial cortex, whereas a vertical osteotomy is committed at the level of the first molar through the lateral cortex. The two osteotomies are joined at the oblique line, and the IAN remains with the distal, medial segment. An intervening block of bone is removed from the anterior aspect of the proximal (lateral) segment if the mandible is intended to be retropositioned. Contralateral osteotomies are conducted in a similar fashion, and the degree of advancement or recession is adjusted as dictated by the occlusal wafer. Figure 12-8 (A,B)This 18-year-old Caucasian woman underwent orthognathic surgery. She was jaw deficient and required a sagittal-split osteotomy with a sliding genioplasty to address the lower aspect of her facial skeletal disharmony. (Courtesy of Edward W. Chang, M.D., D.D.S.)

Skeletal Surgery in the Asian Face

♦ General and Anatomic Considerations

♦ Advancement and Recession Surgeries

Maxillary Advancement/Recession

Surgical Technique for a Le Fort I Osteotomy

Surgical Technique for Maxillary Anterior Segmental Osteotomy

Mandibular Advancement/Recession

Preoperative Remarks

Surgical Technique for the Vertical-Subcondylar Osteotomy

Surgical Technique for the Sagittal-Split Osteotomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree