Although greater respect may be conferred today on dorsal refinement and other aspects of rhinoplasty, there is no subject in rhinoplasty on which more is expounded than the nasal tip. The sheer complexity of nasal tip alteration may account for our fascination with it. Most surgeons even now support the age-old aphorism “He who masters the tip masters rhinoplasty.” Advancements in our understanding of nasal tip anatomy and dynamics have allowed for technical innovations in tip alteration while better preserving structural support and functional integrity. Despite these developments, the incidence of revision rhinoplasty remains considerable. Kamer and McQuown,1 in 1988, reported rates of revision rhinoplasty in the range of 8 to 15%, whereas more recent reports have placed the incidence closer to 5%, albeit for experienced surgeons.2,3 We have previously reported4 a 6% revision rate in our own patients in 1990. This general decline may be attributed in part to greater knowledge and understanding or perhaps to increasing acceptance and employment of open rhinoplasty approaches by less-experienced surgeons.5

Residual and iatrogenic aesthetic deformities are the primary indications for revision; however, a functional deficit co-exists in roughly two thirds of patients.6,7 Although our experience reflects a higher revision rate for midvault abnormalities, several studies spanning five decades indicate lower third deformities to be the leading basis for revision surgery.2,7–9 Patterns of deformities exist, which may reflect a failure of philosophy, understanding, or ability to accurately diagnose and properly implement techniques during the primary procedure. Even in the presence of accurate diagnosis, the capacity to execute satisfactorily may be diminished in revision surgery for several notable reasons: (1) tip anatomy is typically distorted, sometimes severely so; (2) prior overreduction may have compromised tip supports, necessitating augmentation procedures; (3) problematic functional considerations requiring grafting may supersede aesthetic goals; and (4) the presence of fibrosis may have damaged cutaneous vascularity, rendering redrapage unpredictable and less forgiving.4

The discerning rhinoplasty patient is often unaware of these technical improbabilities and will seek opinions until the promised correction materializes. The onus lies with the astute surgeon to precisely analyze existing deformities, to aptly select and educate patients, to distinguish reasonable aesthetic and functional goals from those unattainable, and to implement these with exactitude. Only then will the shared objectives of patient and surgeon translate to a gratifying result.

Anatomy and Nasal Tip Dynamics

Anatomy and Nasal Tip Dynamics

The complex anatomy of the unaltered nasal tip can be difficult to assimilate for the novice surgeon, let alone once it has been distorted by iatrogenic means. Surgeons hoping to achieve refinement or correction of the deformed nasal tip must first have a clear grasp of the multifaceted effects that each maneuver will have on the major nasal parameters of length, projection, rotation, and lobular definition. It is helpful to bear in mind a conceptual framework within which to build a surgical approach. One such notion in ubiquitous use today is the tripod concept, first advanced by Jack Anderson10 in 1969. This concept represents a distillation of the complex tip anatomy by likening the conjoined medial and divided lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages to the three legs of a tripod. Shortening of any leg, such as by division of the medial or lateral crura at their feet, has a predictable outcome on nasal tip parameters. Befitting any workable philosophy, this conception is potent by virtue of its elegant simplicity. However, the tripod concept was conceived at a time when reduction tip rhinoplasty was the norm. Thus, it does not provide for understanding of issues relating to lengthening of the crural elements. In addition, the tripod concept predates the further characterization of tip anatomy to include the intermediate crura, and, therefore, it does not address the effects of alteration of this structure to achieve refinement of the lobule.

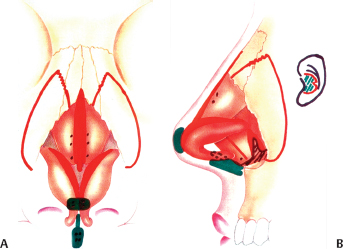

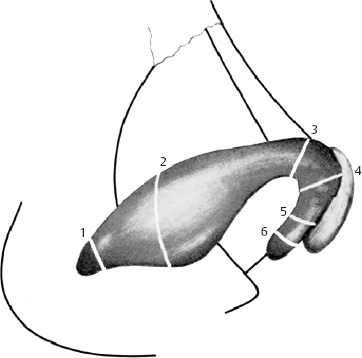

In an effort to expand the utility of the tripod concept, the senior author (PAA) has conceived of a contemporary model of nasal tip dynamics, termed the M-arch model. This notion considers the lower lateral cartilages in their entirety as a tripod arch. The designation M-arch derives from a resemblance of the tripod arch to the golden arches of the McDonald’s Corporation, a symbol universally recognized and firmly established in our culture. Consider the arch of the lower lateral cartilage in three dimensions, in that it projects posterosuperiorly as it extends laterally. The arch is nearly parabolic in shape, with its vertex delimiting the tip-defining point or line. Through this conceptualization, the surgeon may understand the influence of arch modifications on its shape and projection in both an anteroposterior and cephalocaudal dimension. The most significant determinants of tip alteration are the overall length of the arch and the site of the alteration. Shortening the arch close to the vertex will have a greater effect on projection, whereas shortening to the same extent further from the tip-defining point will more greatly influence rotation. Furthermore, shortening of the arch lateral to the tip-defining point serves to deproject, rotate, and shorten the nose, whereas shortening medial to this point will deproject, counter rotate, and lengthen the nose. The degree of change is dependent on the length of the shortened segment and on the distance from the tip-defining point. We define division of the arch at any point along its length as a vertical arch division (Fig. 7–1). Division within the domal or lobular segment of the arch, comprising the intermediate crus and the anterior segment of the lateral crus, we term a vertical lobule division. Vertical lobular division within the intermediate crus, if performed correctly, it is a powerful tool to achieve deprojection, rotation, and lobular refinement. Owing to the ability to alter the length and orientation of the domal arch, vertical lobule division can be applied predictably to diminish a hanging infratip lobule, to narrow a broad biconvex domal arch, to correct tip asymmetries, and to improve nostril-to-lobular relationship where the infratip lobule height is relatively long.

Figure 7–1 A schematic demonstrating the various sites to divide the lower lateral cartilages: (1) hinge area, (2) lateral crural flap, (3) Goldman maneuver, (4) vertical lobule division, (5) Lipsett maneuver, and (6) medial crural feet.

Conversely, the M-arch model can be applied to lengthen the arch to increase tip projection and lobular definition. This is accomplished most commonly by suture techniques, such as single dome unit and double dome unit mattress sutures, and the lateral crural steal technique, to narrow and medialize the domal arch, thereby creating a new tip-defining point. In addition, a columellar strut may help maintain medial crural length, and lobule grafts may increase the apparent length of the arch, thereby increasing projection.

Etiology

Etiology

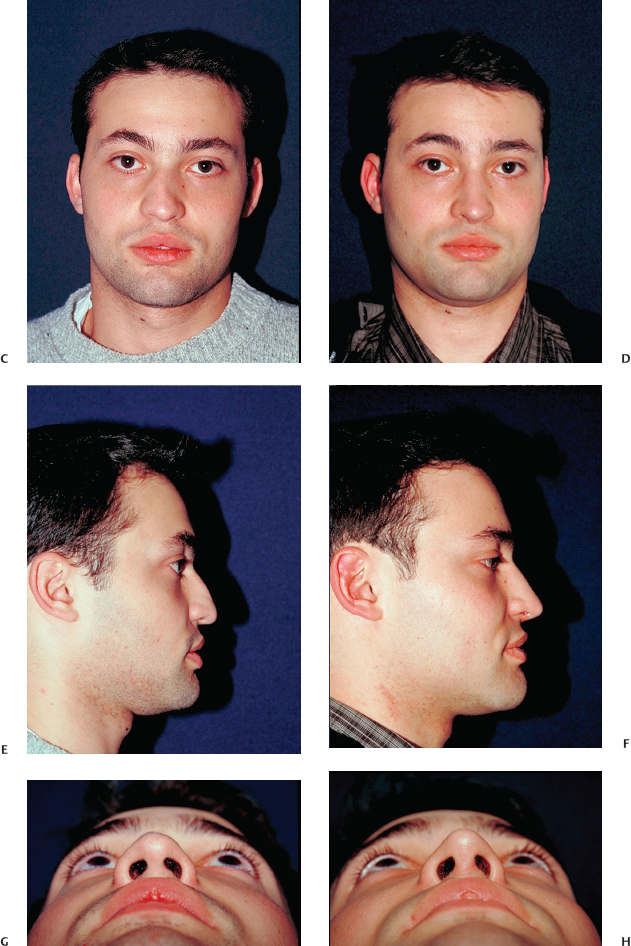

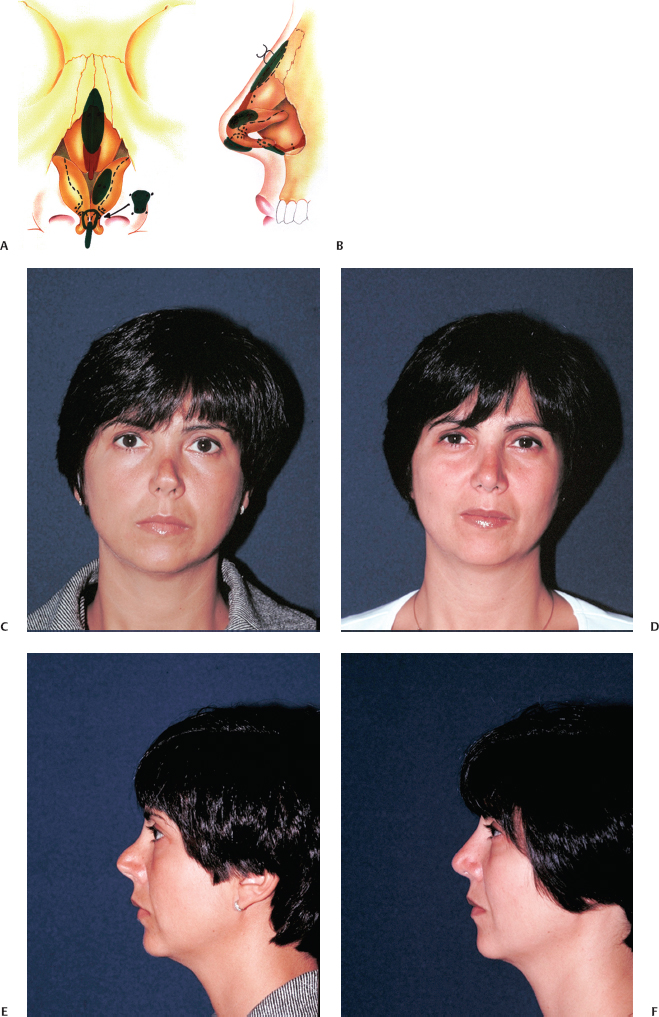

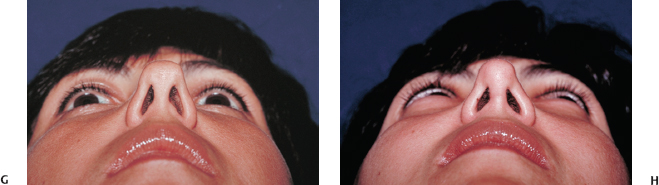

Postrhinoplasty tip deformities can largely be categorized as defects resulting from a failure to address unsatisfactory native anatomical features and those brought about by flawed or overzealous efforts at tip alteration.11,12 Persistent primary deformities include features that were inadequately attended to in the preliminary setting (Figs. 7–2, 7–3). These may be attributed to an oversight in diagnosis or failure to properly account for soft tissue redrapage effects. Examples include the following: (1) a persistently overprojected nasal tip; (2) a counter-rotated or ptotic tip, giving the appearance of an elongated nose; (3) a wide, boxy, or bulbous tip lacking in definition; (4) a cartilaginous or soft tissue pollybeak; (5) a discordant alar-columellar relationship; and (6) a broad or flared alar base.

Figure 7–2 (A, B) Operative schematic for correction of an incomplete primary tip deformity. (C,D) Frontal, (E,F) lateral, and (G,H) basal views before and 1 year after revision rhinoplasty.

Figure 7–3 (A, B) Operative schematic for correction of an incomplete primary tip deformity, (C,D) Frontal and (E,F) lateral views before and 1 year after revision rhinoplasty. (G,H) basal views before and 1 year after revision rhinoplasty.

By contrast, aggressive reductive efforts at primary surgery may give rise to the spectrum of overresected nasal tip deformities (Figs. 7–4 through 7–6). Instances of these abnormalities include the following: (1) an underprojected or collapsed tip; (2) an overrotated tip, leading to a shortened nasal appearance; (3) alar-columellar line or contour irregularities caused by knuckling or bossae formation, alar retraction or a hanging columella effect, a unitip deformity, or grafts that have become visible or palpable; (4) a supratip deficiency; (5) an aggressively narrowed alar base; and (6) external soft tissue irregularities caused by excessive soft tissue thinning or unsatisfactory scar formation.

The functional consequences of these deformities must not be overlooked. In the lower nasal third, these include external valve collapse, caudal septal deflection, and vestibular stenosis. Overresected lower lateral cartilages are typically easily identifiable; however, frail or malpositioned native cartilages may be less readily apparent contributors to valve collapse. The judicious surgeon is ever vigilant in his or her evaluation of the postrhinoplasty tip in hopes of avoiding possible pitfalls of revision tip – surgery.

Indications for Surgery

Indications for Surgery

The import of patient selection in achieving consistently satisfactory results cannot be overstated. It is essential for the incisive surgeon to stratify patients according to risk for potential disappointment, both technically and psychologically. The desirable rhinoplasty candidate has a clearly defined and realistic complaint of long duration. One must remember that the degree of subjective concern that a patient experiences bears no direct relationship to the objective severity of the defect.13 Thus, reasonable distress over a minor deformity does not by itself render a poor surgical candidate. Equally important, the defect must be technically amenable to surgical amelioration in the surgeon’s hands. The prudent rhinoplasty surgeon will therefore be rigorously self-critical of his or her skill set in assessing the probability of success. The surgeon must sense that a sound rapport has been developed with the prospective patient—one that will weather potential turbulence in the future. Several additional patient characteristics are nonnegotiable. The patient must be physically fit and psychologically prepared for yet another surgery. He or she must clearly understand and accept the likely range of outcomes, the limitations, and the risks of surgery. Active participation in, and acceptance of partial responsibility for, postoperative care should be solicited preoperatively. In our own practice, we apply the previously mentioned selection criteria stringently before embarking on revision surgery.14,15

Contraindications for Surgery

Contraindications for Surgery

The undesirable rhinoplasty candidate can be deduced by corollary. However, identifying this patient in consultation is not always as transparent as it appears. Increased probability of a successful relationship can be attained by allotment of adequate time and care for exploration of the patient’s expectations, aspirations, and motivations. In practice, most patients lie somewhere along the continuum between the excellent candidate and the obviously poor one.14,15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree