Nasal septal perforations can be problematic to patients and challenging to surgeons. The perforated nasal septum often has obliterated surgical tissue planes that may be difficult to dissect. Although the literature suggests numerous techniques for management and repair, a more limited number of techniques have achieved widespread favor. In this chapter, we provide an overview of the anatomy, pathophysiology, and evaluation of nasal septal perforations and describe the general principles behind the more commonly used repair techniques.

A similar problem faced by the revision surgeon is a previously operated septum with persisting deviation. As with septal perforations, obliterated surgical planes can complicate the surgical management of this problem. Endoscopic techniques are extremely beneficial in this circumstance, and they are described in this chapter.

Anatomy of the Nasal Septum

Anatomy of the Nasal Septum

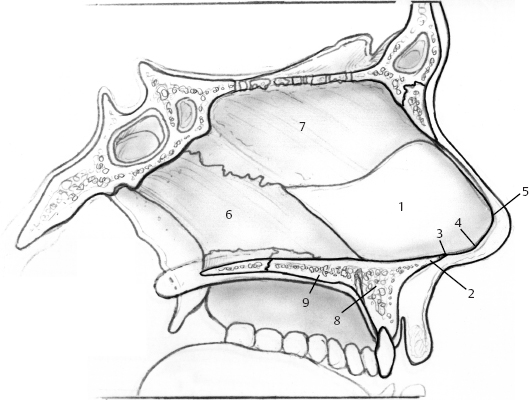

The nasal septum has a posterior bony portion and an anterior cartilaginous portion terminating in connective tissue (Fig. 5–1). The bony portion consists of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone superiorly and the vomer inferiorly. The cartilaginous portion extends to the nasal vestibule. The anterior-most septum, or caudal septum, is attached to the medial crura by connective tissue. This connection constitutes a major tip support mechanism. Septal cartilage is approximately 2 mm thick superiorly and 4 mm thick inferiorly.1,2

The anterior ethmoid artery arises from the ophthalmic artery, passes through the cribriform plate from the anterior cranial fossa to the roof of the nasal cavity, and divides into anterior septal branches and anterolateral nasal branches. Branches from the anterior ethmoid artery provide vascular supply to the anterior and superior septum. The posterior ethmoid artery has branches that supply the posterior and superior portion of the septum.

The sphenopalatine artery arises from the maxillary artery in the pterygopalatine fossa and passes through the sphenopalatine foramen to enter the nasal cavity from below. It divides into posterior septal branches and posterolateral nasal branches. An anterior branch of the sphenopalatine artery runs typically just below the middle of the septum to anastomose with a vascular network known as Kiesselbach’s plexus. This plexus also consists of branches of the anterior ethmoid artery, the superior labial artery, and a nasopalatine branch of the lesser palatine artery that enters through the incisive canal.1,2

Etiology

Etiology

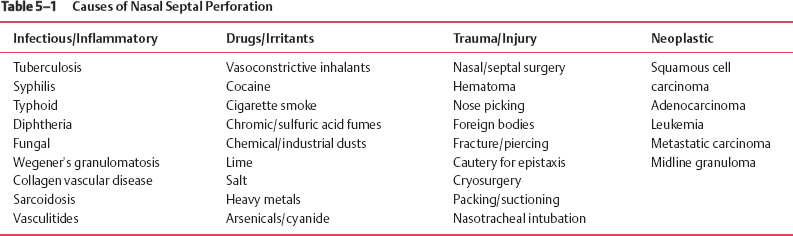

Septal cartilage depends on its overlying mucous membrane for blood supply. When this membrane is injured in corresponding areas bilaterally, the septum is devascularized. Although some causes of mucosal and septal injury are easily recognized, others will not have a readily identifiable underlying disease process. A thorough evaluation may lead to the identification of one of the potential etiologies of nasal septal perforations listed in Table 5–1.1

The most frequently recognized cause of nasal septal perforation is iatrogenic and is associated with nasal surgery and nasal procedures.3,4 Tight nasal packs and electrocautery can impair the mucoperichondrial blood supply or damage the mucosal membranes of the nasal septum directly. Direct injury from surgical intervention, including septoplasty, rhinoplasty, endoscopic sinus surgery, and cryotherapy are recognized as frequent causes of nasal septal injury.

Mechanical or chemical irritation of the septal mucosa may lead to septal perforation, especially if the irritation is chronic. Chronic decongestant nasal spray and cocaine use cause direct vascular impairment through their vasoconstrictive effects. Cocaine also tends to be mixed with other substances that are irritating to the nasal mucosa. Mucosal irritation and impaired blood supply predispose to infection, which complicates the disease process and contributes to septal perforation and additional bone and structural tissue loss. Chronic use of certain nasal steroid sprays also has been associated with septal perforation.

With regard to mechanical causes, habitual nose picking may cause bleeding, crusting, and ulceration, with secondary impairment of blood supply, ischemia of cartilage, and perforation. Foreign bodies inserted in the nose also may cause septal perforation by similar mechanism. The damaging effects of any irritant are compounded by cigarette smoke.1,3

Traumatic injury to the nose with septal mucosal injury or untreated septal hematoma can lead to fibrosis, infection, abscess, and resultant perforation. All patients suffering nasal injury and possible fracture therefore should undergo a careful examination, including rhinoscopy, to evaluate for the possibility of injury to the septum.

Patient Evaluation

Patient Evaluation

Clinical Presentation

Approximately two thirds of nasal septal perforations are asymptomatic; thus, many are discovered incidentally.5 More anteriorly located perforations are more likely to be symptomatic. Table 5–2 lists the common presenting symptoms of patients with nasal septal perforation.

Crusting, bleeding, and difficulty breathing are the main symptoms associated with larger perforations, whereas whistling tends to be more frequently associated with smaller perforations.6 Crusting occurs after desiccation of the nasal mucosa due to replacement of normal laminar inspiratory air currents by turbulent air currents and lower air humidification.3 Persistent irritation and low-grade inflammation impair the healing process over the exposed cartilage and lead to bleeding. Dried blood and crusting obstruct the nasal airway and can make breathing difficult. Pain is usually a result of the localized inflammatory process.

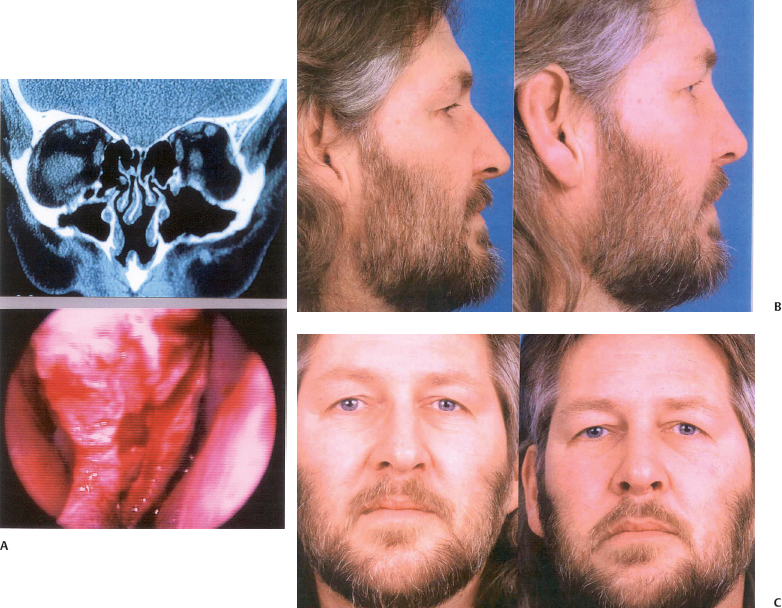

Patients with septal perforation may also present with a cosmetic deformity, specifically with a saddle nose. This deformity may vary in severity from the mildest saddling to severe saddle nose with total nasal collapse (Fig. 5–2).

Posterior perforations are usually less symptomatic because of rapid air humidification by the anterior nasal mucosal lining. Therefore, these perforations often cause no debility and typically do not require repair.

History and Physical Examination

It is important to obtain a thorough history of the patient presenting with septal perforation to establish an etiology, if possible, before reparative surgery. The patient should be questioned about a history of acute or chronic nasal disease, any previous history of systemic disease, previous nasal instrumentation or surgery, a history of facial trauma or habitual nose picking, use of prescribed and nonprescribed medications or nasal sprays, use of any illicit drugs, hazardous occupational exposures, and exposure to first- or second-hand cigarette smoke. Active infectious, inflammatory or systemic disease, or cocaine abuse within 6 months of presentation should preclude reparative surgery until infection is eradicated, inflammation is controlled, and the patient has had adequate time and support for appropriate behavioral modification.6,7

| Crusting | Postnasal drip |

| Epistaxis | Hyposmia/anosmia |

| Difficulty breathing | Dry nose |

| Whistling | Dry mouth |

| Localized pain | Voice changes |

| Rhinorrhea | Foul odor |

| Headache | Aesthetic deformity |

The physical examination likewise should contribute to establishing an etiology. All patients should have a thorough head and neck evaluation. Removal of nasal crusts and decongestion of the nasal mucosa helps the surgeon visualize the entire nasal septum. Appropriate visualization with nasal endoscopes makes it easier to see small and posterior perforations. The location and size of the perforation should be noted and recorded, and attention should be paid to the edges of the perforation and the shape of the mucosa and cartilage immediately surrounding it. The presence of inflamed and crusted mucosal edges suggests an unfavorable local environment that must be addressed before any planned repair.

The surgeon should evaluate for other causes of nasal obstruction, such as sinusitis or persistent septal deviation (Fig. 5–3). If the surgeon simply assumes that a patient’s nasal obstruction is because of an existing perforation, then another cause of the patient’s obstruction may be overlooked, and the patient may have persisting symptoms despite surgical intervention.

Concomitant external collapse of the nose may occur with a large septal perforation when this results in loss of structural nasal support (Fig. 5–2).

Unless the history and physical examination establish a clear etiology, additional work-up should ensue. The antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test, antiphospholipid, and Epstein-Barr Virus titers; nasal bacterial and fungal cultures; the purified protein derivative skin test for tuberculin; and the venereal disease research laboratory test may collectively help establish a diagnosis. Biopsies of any granulation tissue should be performed for pathologic evaluation and to rule out a neoplastic or active inflammatory process. Biopsies should be performed in the posterior direction, when possible, to decrease the vertical height of the perforation and to minimize anterior extension of the perforation with worsening of symptoms.3 It is also important to biopsy a sample of tissue extending away from the inflamed edge of the perforation so that the pathologist has adequate tissue to make a potential diagnosis. Patients with suspected granulomatous disease should have a computed tomography (CT) scan of the nose and paranasal sinuses.

Figure 5–2 External collapse of the nose may occur with a large septal perforation when this results in loss of structural nasal support. This patient’s saddle nose deformity (A) was addressed via an external rhinoplasty approach and reconstruction with an intercalated rib graft (B). Closure of the large, well-mucosalized septal perforation was not undertaken.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Asymptomatic patients rarely require treatment. Patients with mild symptoms, usually consisting of crusting and dryness, often benefit from frequent nasal irrigations with normal saline solution, sometimes with the addition of ointments and emollients (e.g., mupirocin and others). The addition of a mildly acidic substance to the irrigation solution (e.g., vinegar, boric acid powder) helps reduce Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus colonization of the crusty nose.4

For symptomatic nonoperative candidates, a medicalgrade Silastic (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) prosthesis may be of benefit. These come in prefabricated sizes or can be made by a prosthetist if given measured dimensions. Prosthesis insertion is more likely to be successful if it is trimmed to fit comfortably and without applied pressure to the nasal cartilages or nasal floor. A better fit is maintained when the portions of septum anterior and posterior to the perforation are straight.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree