2

Relevant Surgical Anatomy for Rejuvenation of the Aging Face

Wayne F. Larrabee and Samson J. Lee

Surgical techniques for rejuvenation of the aging face have evolved tremendously over the past few decades. This has coincided with a better understanding of the relevant anatomy and the implications of the aging process. Familiarity with the relevant surgical anatomy allows the surgeon freedom in performing surgical dissection in a safe and efficient manner. If a surgeon is hesitant because of uncertainty about important structures, it limits the degree of dissection, ability to manipulate tissue, and may affect results. The first step in evaluating a patient for potential cosmetic surgery is facial analysis.

♦ Facial Analysis

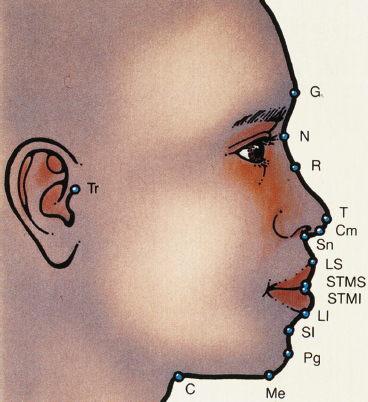

The key to obtaining consistent results in aging face surgery is recognizing the changes associated with aging. Facial analysis should first take into account the sex, race, and age of the individual. Symmetry of the face and any weakness of facial movement should be evaluated and noted. Quality of hair and presence of alopecia should be documented. It is helpful to identify recognizable soft tissue cephalometric points to allow for uniformity in description (Fig. 2.1).

The face can be divided into facial aesthetic units.1 These aesthetic units share similar color, texture, thickness, and mobility of skin. These aesthetic units can be further subdivided for the forehead, nose, and lips (Fig. 2.2).2

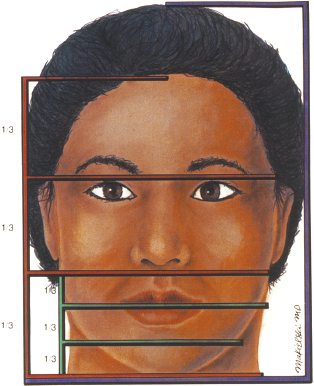

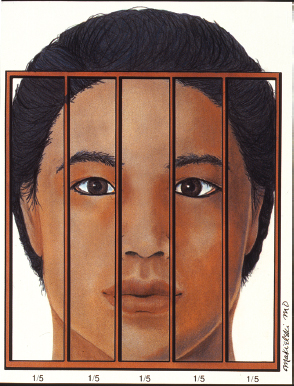

The face is divisible horizontally into thirds and vertically into fifths. The upper horizontal third extends from the trichion to the glabella, the middle third extends to the subnasale, and the lower third extends to the menton. The anterior hairline is usually located 7.5 to 9.5 cm from the glabella. The lower third can itself be further divided into thirds from the subnasale to stomion to mentolabial sulcus to menton (Fig. 2.3). The face can also be divided into fifths based on the lateral projection of the helix to the lateral can-thus, lateral canthus to medial canthus, intercanthal distance, and so forth (Fig. 2.4). Intracanthal distance averages 28 to 30 mm. Faces can come in several aesthetically pleasing shapes, but the oval shape is considered the most pleasing. This corresponds with a 3:4 (height:width) ratio of the face.

Fig. 2.1 The glabella (G) is the most prominent point in the midsagittal plane of the forehead. The nasion (N) is the deepest depression at the root of the nose in the midsagittal plane. The rhinion (R) represents the junction of the bony and cartilaginous dorsum and is usually the maximum on the nose. The tip (T) is the most anterior projection of the nose. The columella point (Cm) is the most anterior soft-tissue point on the columella. The subnasale (Sn) is the junction of the columella with the upper cutaneous lip. The labrale superius (LS) represents the mucocutaneous junction of the upper lip at the midsagittal plane. Similarly, the stomion superioris (STMS) represents the lower border of the upper lip at the midsagittal plane. The stomion inferioris (STMI) and the labrale inferius (LI) are similarly described for the lower lip. The sulcus inferioris (SI) represents the deepest depression in the concavity between the lip and the chin. The pogonion (Pg) is the most anterior point on the chin. The menton (Me) is the lowest point on the contour of the soft tissue chin. The cervical point (C) represents the junction between the submental area and the neck. The tragion (Tr) is the point at the superior aspect of the tragus. (From Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

Fig. 2.3 Horizontal facial proportions. (From Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

Fig. 2.4 Vertical facial proportions. (From Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

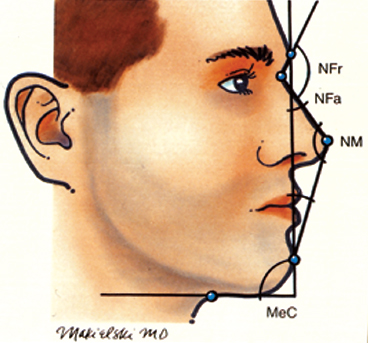

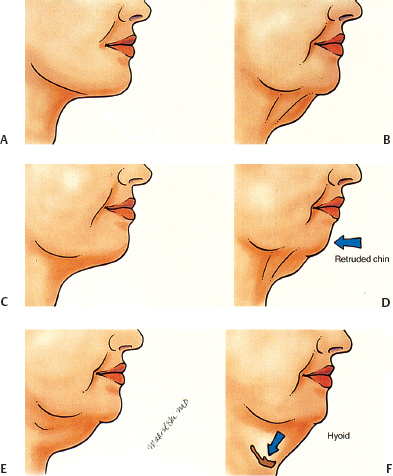

A youthful neck contour can be evaluated by the mentocervical angle. This angle is created by a line drawn from the glabella to the pogonion perpendicular to a line from the cervical point to the menton. This angle should be 80 to 95 degrees (Fig. 2.5).3

Skin

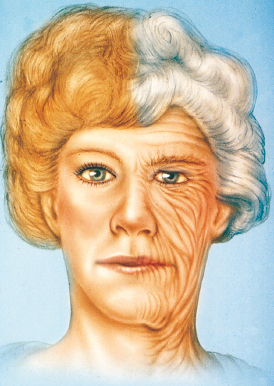

Attention needs to be paid to the quality of the skin. Fitzpatrick skin type should be assessed as well as pigmentary changes. Rhytides, though effaced somewhat by aging face surgery, are better treated by other modalities. This is important to address preoperatively so that the patient has realistic expectations about his or her postoperative outcome. Rhytides can be addressed by resurfacing techniques. As a result of interaction between fixed points, the attenuation in skin, subjacent tissue elasticity, and underlying atrophy of subcutaneous tissue, the accepted younger contours of the face and neck are lost (Fig. 2.6). Aging in all parts of the face including the brow, eyelids, face, and neck should be addressed to avoid an unnatural appearance of treating only one area.

Bone Structure

To further assess the overall improvement possible with surgical rejuvenation, the underlying structure of the face must be evaluated critically. Patients who exhibit excellent bony structure of the cheekbones, chin, and jaw during their youth have the best results, as the redraping of skin helps to highlight these attractive bony structures. Therefore, patients who have a thinner, angular face and good bony definition are generally much better candidates than are patients with rounder faces, low cheekbones, or short mandibles. With aging there is recession of the mandible and alveolar ridge, particularly evident in edentulous patients, which may limit results without augmentation.

Fig. 2.5 Aesthetic triangle of Powell and Humphreys. A vertical line dropped from the glabella to the pogonion defines the vertical anterior facial plane. A line from the nasal tip is then drawn to the nasion. A line from the glabella to the nasion meets this nasal line and creates the nasofrontal angle (NFr). The nasofacial angle (NFa) is between the anterior facial plane and the line tangent to the dorsum of the nose. The nasomental line drawn from the cervical point to the menton intersects the anterior facial plane and creates the mentocervical angle (MeC). (From Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

Adjunctive chin and cheek augmentation may be necessary to achieve the desired result. Patients who have a small chin cannot get the desired cervicomental definition without a chin implant or genioplasty. On a lateral view, the line of Gon-zales-Ulloa gives an estimate of where the chin or pogonion should lie. This line is dropped perpendicular from the nasion and touches the pogonion. In men, the pogonion should touch this line, and in women, the pogonion should approach this line.4 If the pogonion does not approach this line, one must address whether there is microgenia (a small chin but normal occlusion), micrognathia (small jaw with possible class II occlusion), or retrognathia (class II occlusion). In addition, the vertical height of the jaw and chin must be addressed. Deficiencies in the vertical dimension are usually better addressed by genioplasty rather than chin augmentation.5

Additionally, because the aging process sometimes causes a hollow-cheek deformity due to the atrophy of soft tissue or ptosis of the fat pads, older patients sometimes require submalar augmentation or resupport of the fat pads simultaneously with the facelift. Redraping the skin alone does not replace soft tissue cheek hollowness.

Fig. 2.6 Relaxed skin tension lines depicted on the left side of the face. Notice the changes associated with aging: brow ptosis, upper lid dermatochalasis, lateral canthal laxity and inferior displacement, increased scleral show, cheek ptosis, inferior displacement of the ala, development of the nasolabial and melolabial folds, development of jowling, and downturning of the oral commissure. (From Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

As the underlying structures of the face dictate the aesthetic results possible above the jaw line, those in the neck similarly limit the outcome there. In particular, the position of the hyoid bone relative to the mandible varies from patient to patient. This relationship defines the course of the suprahyoid musculature of the floor of the mouth and delimits the maximum improvement possible in the cervicomental angle. A relatively high and posterior hyoid is ideal, allowing maximum elevation of the submental contour and the greatest definition between the submentum and neck in profile. A relatively low and anterior hyoid limits the possible improvement in the area to a predictable degree. With aging, the hyoid and larynx drop inferiorly causing an aged appearance to the neck in addition to changes in the platysma (Fig. 2.7).6

Upper Eyelids

The most important part of the preoperative physical examination is the assessment of visual acuity to prevent confusion if vision decline occurs in the postoperative period. Ocular movement and function should be tested in addition to asking about symptoms of dry eye.

Fig. 2.7 (A) A youthful neck with a sharp cervicomental angle and a strong mandibular line. (B) Early loss of the cervicomental angle and the mandibular line. (C) Chin ptosis, accumulation of submental and submandibular fat, and laxity of submental skin. (D) Accentuation of the previous changes plus banding of the anterior platysma. (E) Further descent and retrusion of the chin. (F) Descent of the hyoid. (From Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

The upper eyelid is evaluated for the quality of the skin, the quantity of excess skin, pseudoherniation of orbital fat, the position and symmetry of the supratarsal crease, blepharoptosis, retraction of the upper lid, and prolapse of the lacrimal gland. Position of the brow is assessed to prevent pulling the brow inferiorly with upper lid blepharoplasty. Pseudoherniated fat is more commonly found in the nasal compartment of the upper eyelid than in the central compartment. Medial compartmental fat tends to be more whitish and fibrous in texture. Gentle ballottement of the globe can make subtle weakness in the orbital septum evident.

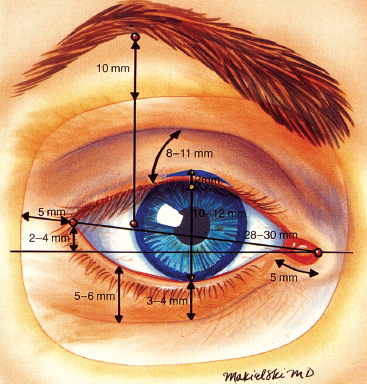

The supratarsal crease is most easily found by lifting the brow and asking the patient to look downward to stretch the eyelid skin, then asking the patient to slowly look upward. The distance from the lash line to the crease at the midpupillary line is 8 to 11 mm in women and 6 to 9 mm in men. If this distance is substantially greater than the reference range, suspect disinsertion of the levator aponeurosis.

Fig. 2.8 The lateral canthus typically lies 2 to 4 mm superior to the medial canthus. Average palpebral opening is 10 to 12 mm in height and 28 to 30 mm in width. MRD-1 + MRD-2 equals 10 to 12 mm. The distance from the supraorbital rim to the inferior aspect of the brow at the lateral limbus is ˜10 mm in Caucasian women. The lower lid crease is ˜5 to 6 mm. The high point of the brow is located superiorly somewhere between the lateral limbus and the lateral canthus. (From Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

Blepharoptosis is determined by measuring the marginal reflex distance (MRD)-1. While the patient remains in neutral gaze, the MRD-1 is measured from the corneal light reflex to the eyelid margin at the midpupillary line. The reference range for MRD-1 is 4.0 to 4.5 mm. Values below the reference range suggest ptosis, whereas values above the reference range suggest upper eyelid retraction (Fig. 2.8). In general, the upper lid margin should sit at the upper limbus. Because orbital fat in the temporal compartment is minimal, fullness in this area should alert the surgeon to the possibility of a prolapsed lacrimal gland and the potential need to reposition the gland back into the lacrimal fossa at the time of blepharoplasty.

Lower Eyelids

The lower eyelid is evaluated for the quality of the skin, the quantity of excess skin, pseudoherniation of orbital fat, retraction, and laxity. Pseudoherniated fat in the lower eyelid occurs in three compartments and is most easily assessed by asking the patient to look upward or by gently balloting the globe with gentle pressure on the upper eyelid skin. Hypertrophy of the orbicularis oculi muscle can be assessed by asking the patient to smile and squint. This maneuver highlights redundant or hypertrophied muscle. Another measurement is the MRD-2, which is measured from the corneal light reflex to the margin of the lower eyelid in neutral gaze. The reference range for MRD-2 is 5.0 to 5.5 mm. Evaluation for ectropion or entropion should also be performed. For both the upper and lower lids, fine wrinkling usually cannot be corrected with blepharoplasty alone, and the patient should be counseled about this preoperatively.

Lower eyelid laxity is measured by means of the snap test and the lower lid distraction test. The snap test is performed by pulling the lower lid downward and outward and allowing the lid to snap back to apposition with the globe. The lid should snap back immediately and into full apposition. If it does not, laxity is suggested. The distraction test refers to how much the lower eyelid can be manually pulled or distracted from apposition with the globe. More than 10 mm of distraction is abnormal and suggests laxity. Another important measurement is the relative position of the medial and lateral canthi in the horizontal plane. The lateral canthus is normally positioned 2 to 4 mm superior to the medial canthus with the eyes open. A position inferior to this suggests laxity (Fig. 2.8).6

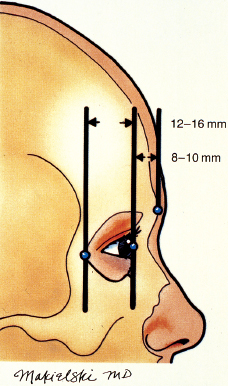

Examination of the position of the globe relative to the orbital rim is important. Removing fat from an already retrodisplaced globe or prominent orbital rim can cause a sunken appearance of the eye and should be avoided or prominence of the lateral orbital rim should be addressed. Typically, the distance from the lateral orbital rim to the apex of the cornea is 12 to 16 mm, and the distance from the supraorbital rim to the cornea is 8 to 10 mm (Fig. 2.9).6

The aesthetics of the lower lid are intimately related to the cheek. Often, to truly address the aging lower lid, the cheek must be addressed in some manner. With ptosis of the cheek fat pad, the vertical length of the lower eyelid increases as the lid-cheek junction becomes more noticeable. To correct this long lower lid and correct the double convexity deformity, the junction between the lid and cheek must be addressed. Often, elevation of the cheek fat pad is not enough, and camouflage of the infraorbital rim is required either by fat augmentation or fat transposition.

Brow

The eyes should be viewed in the context of the entire aging face, especially the forehead and cheeks. The forehead and brows play an important role in the appearance of the eyes. Brow ptosis can account for most of the dermatochalasis in many patients. If blepharoplasty is performed without correcting ptotic brows, the patient is left with a less-than-favorable cosmetic outcome at least and probable worsening of the brow ptosis. For the male patient, brows should be at the level of the orbital rim, whereas the female brow should sit 1 cm above the supraorbital rim. The peak of the brow sits above or just lateral to the lateral limbus in females and is less arched in males. The medial and lateral brow should end at the same horizontal plane. The distal lateral end of the brow should lie at a line tangential to a line adjacent to the ala and lateral canthus.

Fig. 2.9 Relationship of corneal apex to lateral orbital rim and supraorbital ridge. (From Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

Cheek

Qualitative analysis of the cheek can be accomplished by two methods. Hinderer’s analysis of the malar eminence is performed by drawing a line from the lateral commissure of the lip to the lateral canthus. Another line is drawn from the ala to the superior tragus. The area posterior and superior to the crossing of these lines indicates the location of the most prominent part of the malar eminence (Fig. 2.10).

Powell’s analysis is performed by a drawing a line from the ala to the lateral canthus; this parallels a line from the tragus to the lateral commissure. Another line is drawn from tragus to tragus. The intersection of the tragal vertical line with the lateral canthal–ala line indicates the vertical position of the malar eminence (Fig. 2.11).6 Settling of the malar fat pad is common after the fourth decade. As the malar fat pad descends, the infraorbital rim becomes more visible as does the delineation between the lower lid and the cheek complex. This results in the double convexity deformity and increased length of the lower lid. This can be corrected by several methods including midface lift, suborbicularis oculi fat pad (SOOF) lift, orbital fat transposition, or fat augmentation.

Fig. 2.10 Hinderer’s analysis of the malar eminence. (From Larrabee WF, Makielski KH, Henderson JL. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Reprinted with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree