16

Rejuvenation of the Aging Nose

Ted A. Cook and Brian W. Downs

The aging nose presents a unique set of obstacles to rhinoplasty surgeons. In addition to the typical forces of healing and scar contracture acting on the youthful nose, the aging nose features the altered anatomy and physiology of aging added to an already-complicated, three-dimensional structure. Approaching the aging nose requires an appreciation of the nuances of the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases of the patient interaction. Correction of this deformity has both cosmetic and functional implications and can be quite rewarding to the conscientious surgeon.

♦ Nasal Anatomy and Function

Nasal anatomy is commonly divided into three layers, each of which is often considered separately for surgical purposes but must ultimately unite as a harmonious whole. The inner lining refers to vestibular skin and nasal mucosa. The middle layer of the nose is composed of the nasal skeleton: the complex cartilaginous and bony framework that supports the nose, preventing collapse. The outer layer is composed of epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue of varying depths depending on the location craniocaudally on the nose. The aging nose features alterations in all three of these layers. This has direct surgical and functional implications that must be considered during preoperative planning and intraoperative execution. In keeping with our belief that nasal anatomy and function are closely related, these factors will be discussed simultaneously.

Understanding the internal nasal valve is critical to understanding function and dysfunction of the aging nose. First described by Mink,1 the internal valve is defined by the caudal septum, adjacent upper lateral cartilage (ULC), inferior turbinate, and floor of the nose. Aside from aesthetic concerns voiced during the patient encounter, significant time and effort are expended to accurately assess the internal nasal valve preoperatively. Likewise, many of the treatment options discussed later focus on this same structure.

The outer layer of skin and subcutaneous tissue over the nose, like these tissues elsewhere on the body, undergoes changes during the aging process. The skin becomes thinner with a flattening of the dermal-epidermal junction and a reduction in the collagen content of the dermis. This thinning is thought to be related somewhat to hormonal influences, becoming exaggerated in the postmenopausal female. Evidence suggests that this is reversed with hormone replacement therapy.2 The direct surgical implication is that dorsal and tip irregularities are more prominent in the presence of this thinner envelope. This is most pronounced over the dorsum where the skin is already thinnest. Direct and careful palpation of both the dorsum and tip during the preoperative encounter can be helpful in determining skin thickness.

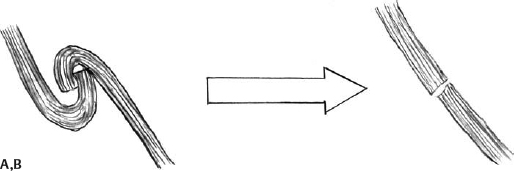

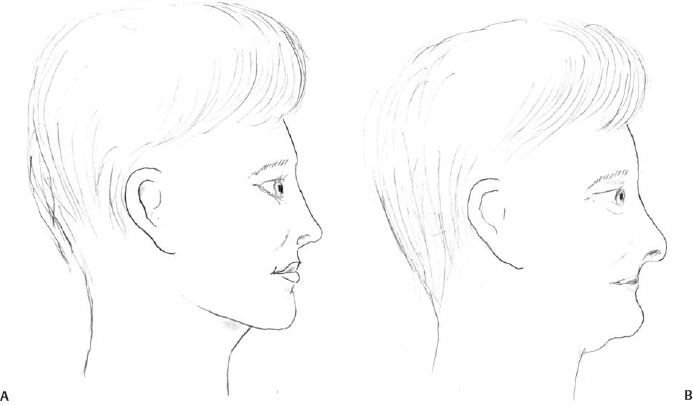

Though the nasal bones themselves remain fairly stable, the cartilaginous skeleton of the nose undergoes significant change with aging. The ULCs become softer and weaker, leading to a nonsupported internal nasal valve and functional nasal obstruction. We refer to this phenomenon as resorbed or palpably-absent ULCs. This is exacerbated by the unraveling of the scroll region—the junction of the ULCs and lower lateral cartilages (LLCs). In youth, the ULCs and LLCs have a “yin-and-yang” relationship, one locked into the other with intervening fibrous connections (Fig. 16.1). With age, the scroll assumes a flattened, almost flaccid configuration, contributing to a lengthening of the lower third of the nose and tip ptosis. These changes are manifest over the dorsum as a pseudohump and an exaggerated supratip depression (Fig. 16.2). Atrophy of the premaxillary fat pad aggravates this deformity.3 Concomitant with these changes, the LLCs themselves soften and the nasal alae lose their resilience.

Moreover, aging changes are present in the region of the columella and caudal septum. The attachments of the septum to the medial crurae are weakened, leading to a lengthening of the membranous septum. Fibrous attachments between the domes and medial crurae relax, which can lead to a “winging” of the medial crural footpods and worsening obstruction (Fig. 16.3).

These anatomic changes together serve to change the configuration of the nares, directing airflow more superiorly in the nasal vault and producing more turbulent airflow. Particulate matter is then filtered less efficiently by the nose. As the body’s hydration status declines, nasal mucosa becomes dry and atrophic with uneven islands of mucus. This filtration inefficiency and static areas of mucus can lead to the sensation of cough and postnasal drip that plagues many patients in the sixth decade and beyond.4

Fig. 16.1 (A) Schematic of the intact scroll region in the youthful nose. (B) Unraveling of the scroll region in the aging nose.

Fig. 16.2 (A) The youthful profile. (B) The aging profile demonstrating exaggerated dorsal pseudohump and tip ptosis.

Fig. 16.3 (A) Winging of the medial crural footpods in the aging nose. (B) Correction of this deformity by suture securing the medial crural footpods to a stable caudal septal extension graft.

Fig. 16.4 (A) Schematic of left-sided septal spur and cartilaginous redundancy along the maxillary crest potentially exacerbated by ptosis of the nasal tip. (B) Septal deflection corrected with caudal end secured in the midline.

In our experience, a septal deflection often accompanies these changes in the aging nose. Anecdotally speaking, this is more often on the left side (Fig. 16.4). We hypothesize that this anatomic defect is secondary to generalized descent of the nasal tip such that over time, the inferior aspect of the quadrangular cartilage is “made redundant” by the primary problem, nasal tip ptosis. As the septum slides off the maxillary crest, a spur is formed, further contributing to the nasal obstruction. Why this occurs more often on the left side is unknown.

The muscles of facial expression located in the midface region, like muscles elsewhere in the body, undergo changes with age. Specifically, the dilator naris muscle innervated by cranial nerve VII is partially responsible for nasal valve competence. Like muscles elsewhere in the body, it would be expected to atrophy with age, becoming less effective. Perhaps more importantly, the dilator naris responds to nasal airway resistance. In the presence of less nasal airflow (less resistance), the muscle can become less active until complete cessation of function is reached.5 This can theoretically lead to a completely adynamic nasal valve. For example, aging individuals who are chronic mouth breathers with nasal obstruction may have causative anatomic factors as outlined above and neurophysiologic ones as well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree