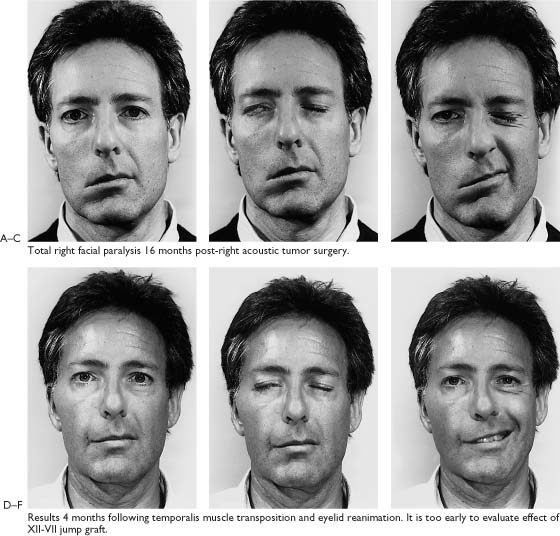

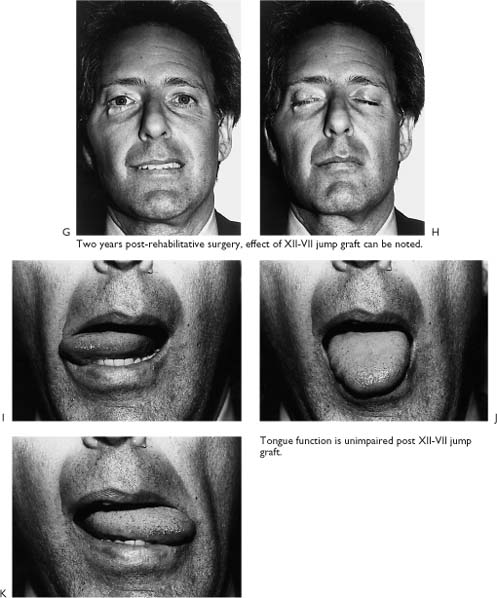

8 The rehabilitation techniques that work have been described in the previous chapters of this section. This is the last chapter on surgical reanimation of the paralyzed face. Six case presentations have been chosen in an attempt to highlight as well as emphasize the benefit of introducing dual systems and combining the concepts proposed in the previous chapters. Each patient with facial paralysis presents with unique problems. Therefore, with each case, I will share my reasoning process involving the following: (1) case selection; (2) how to choose the technique to best correct specific deformities; (3) how to achieve maximum rehabilitation with one scheduled procedure; (4) how to decide the best time for nerve grafting, hypoglossal-facial repair, or temporalis muscle; (5) when is it too late to repair the facial nerve; (6) how to manage recurrent benign tumors and malignant tumors; and (7) what to do when efforts fail to improve the patient’s condition or make the situation worse. The purpose of this chapter is to stress the complexities of surgically rehabilitating patients with facial paralysis. Finally, the physician who masters the material in this book will be ideally positioned to treat the patient with a paralyzed face. Reanimation 18 months following acoustic tumor surgery. A 45-year-old physician presents 18 months post-right acoustic tumor surgery. The facial nerve was sacrificed with the tumor resection. He has not been able to return to work because of eye irritation and emotional depression over his facial deformity. The patient was concerned about his eyes, particularly eye irritation, overflow tearing due to exposure keratitis, and the inability to close the right eye. He was also concerned about the mouth droop which made it difficult to speak clearly and drink liquids without drooling. A, There are no other cranial nerve deficits; tongue and temporalis muscles are normal. On the involved right side, there is loss of forehead creases. The brow is acceptable at rest. There is a prominent tarsal-supratarsal fold. There is drooping of the lower lid, especially in the lateral half. There is slight collapse of the naso-alar fold, loss of lip-cheek crease, and drooping and asymmetry of the mouth.B, Incomplete eyelid closure. C, No movement or formation of facial creases noted as patient voluntarily contracts muscles around eye and mouth. This same maneuver was repeated with the patient in supine position to eliminate the effects of gravity. Sometimes slight movement indicating some spontaneous return of facial function will be noted with patient lying down, but will not be detected with the patient upright. Figure 8-1. After discussion of risks, options, and benefits, the patient was scheduled 1 week later for a XII-VII jump graft, temporalis muscle transposition, gold weight and cartilage implant, and lower lid tightening procedure. D, The patient in repose, 4 months post-rehabilitative surgery. It is too early to appreciate any changes from the XII-VII jump graft. The right lower eyelid is symmetrical with the normal right side. The droop has been corrected. The gold weight is covered by the tarsal-supratarsal fold. The position of the corner of the mouth is improved compared to preoperative photo (A). There is a suggestion of a lip-cheek grove on the paralyzed side. E, Eye closed. Good eyelid approximation laterally with minimal exposure medially. F, Voluntary smile. The temporalis muscle attachment to the lip-cheek crease needs to be tightened. The patient was disappointed because the corner of the mouth was overcorrected for the first 3 weeks, but then the suspension effect was lost over the following 3 weeks. Overall, the patients was pleased with the improvement, especially the eye region. The eye was much more comfortable, and he has returned to work as a family physician. In such a case, with a dual system and the likelihood that improvement would be noted because of the XII-VII jump graft, no effort was made to revise the temporalis muscle procedure (see Chapters 4 and 7). G, Two years post-rehabilitative surgery. At 1 year, tone and movement were beginning as a result of the XII-VII jump graft, and at 2 years, the results are significant. Note the lip-cheek groove, improved symmetry, and movement of the mouth. The effect of the XII-VII jump graft will continue to improve over 5 years. Sessions with a facial rehabilitation physical therapist was recommended. H, Eyes closed. The gold can be seen as a round prominence due to a fibrous pseudocapsule that forms around the implant. Most patients and casual observers are not aware of this deformity because the eyelids are open the majority of the time. Note that the gold is not visible with the eyes open (G). The prominence under the lateral aspect of the lower lid is from the cartilage implant. This can be corrected, if requested by the patient, by trimming that piece of cartilage. In most cases, only the midface and mouth are reinnervated following a XII-VII procedure. However, in some cases, function around the eye as well as the mouth will be restored. In such cases, facial creases will return, and the patient will be able to close the eyelids lightly. If this is observed, it may be possible to remove the gold and cartilage because both procedures are reversible. This would be done only in cases where the gold or cartilage was causing problems. For example, the gold may be unsightly or cause overclosure. Some patients complain that the eyelid with the gold implant tends to close when reading or they are aware of a pressure on the eye. I, J, K, Tongue movements are unimpaired. The XII-VII jump graft is a useful addition to the variety of reanimation options available. This procedure is reliable and satisfies a most important requirement: reinnervation to a recipient without a deficit to the donor. This is a major advantage over the classical XII-VII crossover procedure (see Chapter 4). A 52-year-old woman presents 2 years following tympanomastoid surgery for cholesteatoma and iatrogenic facial paralysis. The paralysis was noted immediately following the surgery. No effort was made to evaluate or treat this problem until now, 2 years after the facial nerve injury. None of the recommendations regarding management of this common problem, iatrogenic injury to the facial nerve during ear surgery, had been pursued (see Chapters 1 and 2). The patient anticipated spontaneous recovery based on the reassurance of the surgeon. When no recovery occurred after 2 years, she sought another opinion. The patient was ashamed and self-conscious of her facial appearance. Her eye on the involved side was uncomfortable in spite of frequent use of artificial tears. Normal speech and eating were impaired, and pain associated with lip biting was common. Collapse of the nasal ala on the involved side caused nasal obstruction. She wanted to know what happened to cause the paralysis and could anything be done to restore her face to normal. I told her that the nerve was most likely injured during the ear surgery and facial reanimation procedures are available to improve her facial appearance and function, but nothing can be done to restore her face to the way it was before the ear surgery. Her expectations were realistic. The patient is 2 years post-tympanomastoid surgery. A, In repose. There is absence of forehead creases. The brow has lost its upward curvature. Prominence of the tarsal-supratarsal fold is prominent. Greater scleral show is noted on the involved left side due to drooping of the lower eyelid. The presence of facial creases in the naso-orbital groove on the left suggests residual innervation or evidence of spontaneous neural regeneration. The nose and mouth are pulled to the normal side, and drooping of the corner of the mouth is striking. The marked asymmetry of the lips is due to denervation of half of the oral sphincter with contraction on the right unopposed by the paralyzed left side. B, Incomplete eyelid closure. C, There is no movement of the facial muscles on the left except the inferior and anterior border of the platysma (arrow). The facial creases under the left eye (arrow) and this subtle platysma finding are evidence of a incomplete injury or some spontaneous recovery. Electromyography did not support any evidence of muscle innervation or signs of regeneration. Computerized tomography (CT) demonstrated a modified radical mastoid cavity in a sclerotic temporal bone on the operated side. Further, in the location of the tympanic segment of the facial nerve, there was a prominence suggesting neuroma. Figure 8-2. After risks, options, and benefits were discussed, the patient was scheduled for transtympanomastoid exploration of the facial nerve and possible repair using the greater auricular nerve. If this was not possible, a XII-VII crossover procedure would be performed. The reinnervation technique would be combined with a temporalis muscle transposition and Gore-Tex suspension of the nasal ala (see Chapter 7). The eye would be reanimated with a gold and cartilage implant, and the lower lid would be tightened.

Reanimation: Dual Systems by Combining Procedures

Mark May, M.D.

Case 1 (Figure 8-1)

Patient’s Concerns

Examination

Management Options

Results

Case 2 (Figure 8-2)

Patient’s Concerns

Examination

Management Options

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree