Fig. 11.1

Lichen planus pemphigoides. Violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped lesions of lichen planus on the lower extremity with a tense, dome-shaped blister

Fig. 11.2

Lichen planus pemphigoides. Clear fluid-filled tense bullae arising on erythematous skin

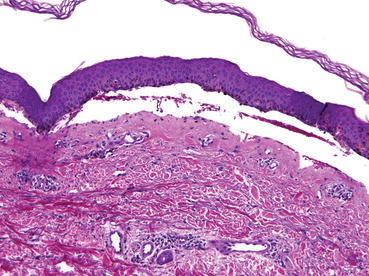

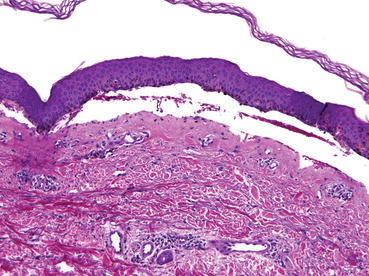

Histologically, the lichenoid lesions of LPP demonstrate classic histopathological features of lichen planus and the bullae demonstrate features of bullous pemphigoid [1]. Biopsy specimens with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining from cutaneous lichenoid lesions demonstrate hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis. Colloid bodies of Civatte are seen in some cases, with a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper papillary dermis. Vesicles and bullae demonstrate a subepidermal blister with associated edema and infiltration of eosinophils, and perivascular mixed inflammatory infiltrates consisting of eosinophils, histiocytes, and lymphocytes [3]. Direct immunofluorescence studies performed on peri-lesional skin biopsies show linear deposition of IgG, C3, and fibrinogen along the basement membrane zone (BMZ) [4]. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) studies demonstrate circulating IgG autoantibodies to keratinocyte cell surfaces. When performed, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests often demonstrate positivity for IgG antibodies to desmoglein-1 (Dsg1), BP180, and BP230 [2–4].

The pathogenesis of LPP is not completely understood. Although most cases are idiopathic, there are few reports of LPP developing in association with drugs, phototherapy, and in one case, hepatitis B virus infection [6–9]. The most common culprit medications reported are angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors such as ramipril and captopril [7–9]. One theory suggests that damage to basal cells in LP can expose sequestered antigens or produce new antigens that lead to autoantibody formation and subsequent bullous lesions. In a study examining circulating antibodies before and after the diagnosis of LPP, autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone were detectable after the development of bullae, but not before. Furthermore, once the bullae were controlled with therapy, anti-BP180 antibodies were no longer detectable [2]. The diagnosis of LPP can be confirmed based on histopathological findings of both LP and subepidermal bullae, and DIF findings of linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 in the BMZ [3].

Systemic Treatment

Systemic Corticosteroids

The use of systemic corticosteroids to treat LPP has been reported most widely in the literature. In greater than half of the cases, systemic corticosteroids alone have been used to successfully treat LPP. In most reports, the bullous eruption resolves within a few weeks of therapy and while there have been relapses reported in patients after several years of disease clearance, the recurrence rate of LPP appears lower than the rate seen in bullous pemphigoid. The recommended dosage is 0.5 mg/kg daily, or 40–60 mg daily for adults [10].

Although systemic corticosteroid therapy is an effective first-line therapy that has demonstrated good clinical response, there are undesirable side effects, particularly in children. In rare reports of LPP in children, different systemic agents were required after difficulty tapering systemic steroid treatment. In one case of LPP in a 2-year-old child, the disease was controlled with systemic corticosteroids at a dose of 2 mg/kg daily. However, attempts to taper the dose below 1 mg/kg daily resulted in recurrent flares of severe bullous disease. The patient was begun on low dose methotrexate and was able to be successfully tapered off systemic steroids [11]. In another case of LPP in a 6-year-old child, topical corticosteroid therapy resulted in no response, and oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg/day resulted in the cessation of bullae formation within 4 days. However, tapering resulted in flares at 5 and 10 weeks, and again when steroids were stopped. During 2 years of follow-up, the patient had recurrence of LP lesions but not bullous lesions [5].

Dapsone

Dapsone (4,4′-diaminodiphenyl sulphone), traditionally used as an anti-infectious agent, has demonstrated many uses for noninfectious inflammatory dermatologic diseases. There are several cases in adults and children that have documented the successful treatment of LPP with dapsone, either as a single agent or in combination with other systemic agents. In two reports of adults with LPP, dapsone was used in conjunction with oral methylprednisolone and resulted in disease control. After 12 weeks on oral steroids and 16 weeks of dapsone, one patient had no recurrence of any skin lesions after 1 year [12]. In another patient who was previously treated with erythromycin and nicotinamide with little response, dapsone 50 mg daily was used with topical corticosteroids. Within 1 week, bullous lesions began to regress and dapsone was continued for 4 months until complete clearance was achieved. Over 18 months of follow-up there were no recurrences of bullous lesions, although lesions of LP recurred and were managed with topical corticosteroids [13]. There are also reports of poor response to dapsone. In a patient treated with dapsone 100 mg/day, no response was seen after 2 weeks. Once therapy was switched to oral methylprednisolone, there was expedient resolution of skin lesions and steroid therapy was discontinued after only 2 months [12].

In a report of two cases of childhood LPP, both patients were treated successfully with a combination of topical corticosteroids, oral prednisolone, and dapsone. In one patient, clinical remission was achieved within 10 months, and BP180 ELISA remained borderline positive. In another patient, systemic treatment lasted for 19 months, and the patient had mild recurring LP plaques 2 years later that responded to topical steroids, while the BP180 ELISA remained borderline positive [4].

Antibiotics and Nicotinamide

The combined use of antibiotics and nicotinamide (or niacinamide) has been reported in autoimmune bullous diseases. This combination of drugs acts to inhibit neutrophil or eosinophil chemotaxis, inhibit antigen-induced histamine release, suppress antigen responses, and suppress lymphocyte transformation [14]. In the treatment of LPP, therapy with erythromycin and nicotinamide has been reported in children, whereas tetracycline antibiotics have been used in adults, with varying success. In a child diagnosed with LPP, the patient was to begin therapy with dapsone 50 mg daily and topical steroids, but while awaiting the results of glucose-6-phosphatase testing, began treatment with oral erythromycin 30 mg/kg daily in four divided doses and nicotinamide 150 mg three times a day. After 1 week, this was then replaced by dapsone 50 mg daily and topical steroids. The patient had cessation of new bullae within 1 week, and had complete clearance by 4 months. After an 18-month period of follow-up, the patient had no recurrence of bullae, and lesions of LP were treated with topical corticosteroid therapy [13].

In an adult with LPP, initial treatment with oral prednisone induced remission of the disease, but in the presentation of a new flare 3 years later, the patient was treated with tetracycline 500 mg four times daily and nicotinamide 500 mg three times daily. This regimen led to rapid clearance of skin lesions, however, tetracycline was replaced with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily due to the development of renal insufficiency. Bullous eruptions recurred at each attempt to discontinue doxycycline and nicotinamide, and would respond to reinstitution of both drugs [14].

Other Immunosuppressive Agents

Methotrexate has been used as an adjuvant immunosuppressive agent with prednisolone. In one report, a young child with LPP demonstrated response to prednisolone 2 mg/kg daily, but attempts to taper below 1 mg/kg daily resulted in a severe flare of the bullous component of the disease. Methotrexate 0.5 mg/kg daily was initiated and led to disease clearance after 4 weeks of treatment, and prednisolone was tapered over 8 weeks. Follow-up testing of serum anti-BP180 autoantibodies demonstrated decreasing levels along with clinical improvement. After 11 months of treatment with methotrexate, serum level of anti-BP180 autoantibodies decreased from 173 to 42 U/mL and the patient had no recurrence of disease during follow-up [11].

There are sparse reports of azathioprine being used as an adjunctive treatment for LPP. Only one case has been reported in which a patient was treated with combination therapy with prednisolone 40 mg daily, azathioprine 100 mg daily, and topical steroids. Disease control was maintained with prednisolone 25 mg and azathioprine 100 mg daily, although there was no report of subsequent follow-up [10].

In a case of prednisolone-resistant LPP, a patient with extensive lesions involving the soles and oral mucosa was treated with low dose cyclosporine A in combination with prednisolone. After the patient had minimal response to prednisone at 0.4 mg/kg daily, low dose cyclosporine A at 2 mg/kg daily was added and led to improvement of vesicles and bullae. As the patient’s clinical lesions improved and the anti-BP180 antibody titer index decreased, cyclosporine A and prednisone were tapered, and the patient remained in remission [15].

Current Opinions

Lichen planus pemphigoides has features of both bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus, which can make treatment with just one modality suboptimal. Based on the severity of the disease, which is defined by the extent of body surface area involvement and severity of symptoms such as pruritus, treatments range from topical therapy to systemic immunosuppressive agents. Topical corticosteroids are an effective and safe first-line treatment in patients with limited cutaneous involvement, as it is used to treat both localized lichen planus and bullous pemphigoid. In cases with extensive cutaneous and/or mucosal involvement requiring systemic treatment, the most studied therapeutic agent for LPP is oral prednisolone. Compared to bullous pemphigoid, LPP has a much younger age of onset and typically follows a less severe clinical course, which makes corticosteroids a reasonable first-line treatment option. However, in patients with contraindications to systemic steroid therapy or in young children, dapsone is the next most commonly reported agent. Dapsone has demonstrated favorable results particularly in younger patients in whom chronic therapy with systemic corticosteroids is undesirable. However, if there are contraindications to dapsone such as glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency or the development of hemolytic anemia, other immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine can be considered, although the literature reporting on the efficacy of these agents is sparse and anecdotal (Table 11.1). The use of combination therapy with antibiotics and nicotinamide is less favorable due to reports of patients with indefinite treatment duration and disease flares associated with discontinuation.

Table 11.1

Summary of rare autoimmune bullous diseases and treatment algorithm

Disease | Clinical presentation | Histology | Immunofluorescence | 1st line treatment | 2nd line treatment | 3rd line treatment (anecdotal evidence only) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lichen planus pemphigoides | Lesions of lichen planus with tense vesicles and bullae in areas of LP and normal skin | Hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and band-like lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper papillary dermis, with subepidermal blister with associated edema and eosinophils | DIF: Linear deposition of IgG, C3, fibrinogen along BMZ IIF: Circulating IgG to Dsg1, BP180, and/or BP230 | Systemic steroids (0.5 mg/kg/day) | Dapsone (50–100 mg/day) | Methotrexate Azathioprine Cyclosporine |

Bullous lichen planus | Lesions of lichen planus with vesicles and bullae formation over pre-existing papules and plaques | Hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, basal vacuolar cell degeneration, with subepidermal blister containing fibrin, eosinophils, and neutrophils | DIF: No linear deposition of IgG or C3. Coarse granular deposits of fibrinogen at DEJ only IIF: No circulating antibodies | Systemic steroids (0.5 mg/kg/day) | Dapsone (200 mg/day as single therapy) (25–50 mg/day if used as adjuvant therapy) Acitretin (30 mg/day) | Cyclosporine (1–5 mg/kg/day) |

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus | Vesicles and bullae coalescing to form elongated, arciform, or irregular shapes | Subepidermal blister with neutrophils, karyorrhectic debris with occasional lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils | DIF: Granular or linear deposition of IgG, IgA, IgM, and/or C3 in BMZ IIF: Circulating IgG to type VII collagen (NC1) | Dapsone (25–50 mg/day) | Methotrexate Mycophenolate mofetil | Rituximab Systemic steroids |

IgA pemphigus | Vesicles and bullae that evolve into pustules that coalesce into annular or circinate lesions with central crust | Intraepidermal neutrophilic pustules or vesicles and neutrophilic infiltration in the epidermis | DIF: IgA deposition throughout entire epidermis (IEN) or upper epidermis only (SPD). IIF: Circulating IgA1 only | Systemic steroids (0.5–1.0 mg/kg/day) | Dapsone (25–125 mg/day) Acitretin | Colchicine (0.5–2 mg/day) Adalimumab |

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis | Vesiculopustular lesions that coalesce to form annular or circinate lesions that evolve into crusted lesions with pustules at the periphery | Subcorneal separation with aggregates of keratin and neutrophils within the clef | DIF: Negative for IgA and IgM IIF: No circulating antibodies | Dapsone (50–200 mg/day) | Colchicine (0.5 mg twice daily) Etretinate/acitretin | Infliximab Etanercept PUVA Systemic steroids |

Deciding whether or not to discontinue a therapy or add an additional therapy can be difficult and depends largely on the extent of clinical response. When treating with systemic corticosteroids, many clinicians use the cessation of new bullae formation within the first 7–14 days as a sign of good clinical response in the initial treatment period. Beyond the initial clinical response, the next challenges are achieving a full clinical response and maintaining disease clearance while tapering medication(s). In the rare cases of extensive disease involvement including the oral mucosa, additional therapeutic measures such as dapsone can be useful adjunct treatments. Once disease control is achieved, tapering must be performed with close monitoring, either with follow-up clinic visits or telephone follow-up at a minimum of weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12. There is wide variability in response to tapering medications, evident by the variable lengths of total treatment periods reported in the literature, ranging between 3 and 18 months, and in some cases, indefinite maintenance therapy. While some patients demonstrate disease stability with no recurrence, other patients demonstrate rapid disease recurrence with medication tapering.

Discussion/Areas of Future Interest

There is limited literature on the efficacy of treatment options for LPP. The lack of evidence for the use of non-steroidal systemic agents is likely reflective of the extent of the typical success of systemic steroids in treating the disease. Few studies report on the level of autoantibody titers throughout the course of the disease, although it can be used as a guide for response to treatment. Further research is needed to evaluate the utility of monitoring autoantibody levels and the correlation between autoantibody titers and disease severity.

Bullous Lichen Planus

Clinical Features

Bullous lichen planus is a variant of lichen planus that presents with typical lesions of LP and vesicles and bullae over pre-existing papules and plaques. Unlike LPP, the bullae are often less extensive, and bullae tend to form only in areas of involved skin with lesions of LP, with few bullae rarely occurring in the adjoining skin (Fig. 11.3) [16]. In contrast, the bullous lesions of LPP form on both lesions of LP and normal skin. The bullous component of bullous LP is most prominent during an LP flare and has a similar distribution to lichen planus, with a predilection for the trunk and extremities. Pruritus is a common presenting symptom, which can precede the development of erythematous or violaceous papules and plaques with bullae forming at the periphery. The bullae are tense, non-hemorrhagic, and can form as a group of numerous vesicles [17, 18]. Oral involvement is uncommon but can occur in this entity. It usually presents as fluid-filled vesicles with surrounding reticular white streaks, often on the buccal mucosa and less commonly on the gingiva and inner aspect of the lips [19–21].

Fig. 11.3

Bullous lichen planus. Erosions where bullae occurred within lesions of lichen planus

Histologically, bullous LP demonstrates features of lichen planus such as hyperkeratosis, focal hypergranulosis, prominent basal vacuolar cell degeneration, and band-like lymphohistiocytic cell infiltrates in the upper dermis with few eosinophils that hug the epidermis, leading to the creation of a subepidermal cleft [16]. The subepidermal bullae contain fibrin strands, eosinophils, neutrophils, and occasional histiocytes. Inflammatory cells are also found along the BMZ at the edge of the blister, and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrates can be seen in the papillary and reticular dermis. Although bullous LP can be clinically resemble bullous pemphigoid and LPP, DIF will characteristically lack the linear deposits of immunoglobulins and C3 at the BMZ, and show only reticular and coarse granular deposits of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. Indirect immunofluorescence will demonstrate immunoglobulins in the stratum granulosum with no circulating antibodies [18, 20].

The pathogenesis of bullae in this entity is thought to be due to upper dermal inflammation, extensive liquefactive degeneration and vacuolation of the basal layer [5]. Few cases have reported bullous LP occurring in response to certain drugs such as intravenous contrast, labetolol, and hepatitis B virus vaccines [22–24]. Theories behind this association suggest that drug-induced lichen planus can be initiated by a cell-mediated immune response to an induced antigenic change in the skin or mucosa. From a diagnostic perspective, bullous LP can clinically be mistaken for bullous pemphigoid or LPP; however, the indirect and direct immunofluorescence assays are distinct in bullous LP and will guide the diagnosis.

Treatment

Systemic Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are considered the first-line and the most widely used therapeutic agent to treat lichen planus and its variants [25]. Systemic steroids are used in cases of LP that are refractory to topical therapy, extensive in body surface area involvement, or in exanthematous or ulcerative forms. Lichen planus is generally responsive to corticosteroids, and bullous LP appears to have a similar response profile. In case reports that describe the treatment of bullous LP with systemic steroids, the most common doses reported are prednisolone 0.5–1.0 mg/kg daily. In one report of an adult patient, oral prednisolone 40 mg daily was used to treat bullous LP, and was tapered in 6 weeks leading to regression of all skin lesions and with no disease flare or relapse throughout a 6-month follow-up period [16]. Systemic steroids were also reported in a case of a child with bullous LP, at a treatment dose of 20 mg daily. After treatment for approximately 6 weeks, the patient had good response to therapy with no adverse effects. Oral mini-pulse therapy has also been reported in patients, using 5 mg betamethasone orally as a single daily dose on two consecutive days each week, in conjunction with topical betamethasone dipropionate twice daily. This was tapered to 0.5 mg each week, and stopped after 10 weeks. In pulse therapy, potential side effects are decreased and the authors reported adequate disease control with no recurrence after 12 months [26].

Acitretin

Although there are no specific studies or reports that discuss the use of acitretin in patients with bullous LP, it is one of the only treatments for lichen planus that has been studied in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. In this study, patients with LP were treated with 30 mg acitretin daily for 8 weeks. In 64 % of all patients, there was remission or improvement of symptoms, including pruritus, papulosis, and erythema. Side effects were minimal, with cheilitis and dry mouth being the most commonly reported adverse reactions [25].

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine has only been studied for the treatment of lichen planus in small uncontrolled case series or case reports. This agent is a systemic treatment that can be used for lichen planus after patients have demonstrated resistance or lack of response to acitretin and/or corticosteroids. Doses used in the literature have been reported between 1 and 5 mg/kg daily, as low doses appear to be sufficient to control the disease [25].

Dapsone

Dapsone has been reported in the treatment of lichen planus and its variants, used alone or more often as an adjunctive agent with corticosteroids. In a review of the use of dapsone as a single agent for lichen planus, 92 patients with any clinical variant of LP were treated with dapsone 200 mg daily for 16 weeks. Complete response was seen in 65 % of patients while 19 % achieved partial response to treatment [25]. In other cases, dapsone was used in combination with prednisone, either if prednisone alone did not achieve complete clearance of disease or as an additional agent during the tapering of steroids. In case reports of patients with LP involving the oral mucosa, dapsone appeared to have increased efficacy in improving oral lesions and in tapering prednisone. Patients were initially treated with 40 mg of prednisone daily, and as prednisone was decreased to 20 mg daily, dapsone at 25 mg daily was added to prevent disease flare. However, in another report, low dose dapsone (25 mg daily) and systemic steroids were sufficient to induce remission in a patient, but tapering to low doses of either dapsone or prednisone resulted in disease flares, which were treated with higher doses of dapsone (50 mg for the first flare, and 100 mg for the second flare) [18].

Current Opinions

There are no reports in the literature beyond anecdotal case reports that specifically evaluate or review the efficacy of different treatment methods for bullous LP. This is likely due to the fact that bullous LP is rare, underreported, and often treated by clinicians under the same guidelines used for treating lichen planus, as this clinical variant does not require a markedly different treatment course. By and large, the main difference between bullous LP and classic lichen planus is the presence of bullae, which can be more concerning to the patient, and rupture and lead to the exposure of more cutaneous sources of entry for infection. Although there are few reports suggesting that bullous LP can be more resistant to treatment than classic LP, this generalization is solely based on anecdotal observations and individual experiences, as the incidence of bullous LP within the population of patients with lichen planus is still not well defined. Corticosteroids and acitretin either alone or in combination are the systemic therapies for lichen planus that have been most extensively used and reported. Adjunctive treatment options include cyclosporine and dapsone, with varying reports of success (Table 11.1) [17]. The approach to the treatment of bullous lichen planus is similar to that of lichen planus, although clinicians should be aware of a possibly higher rate of treatment resistance to the typical first or second-line treatments.

Areas of Future Interest

Further studies on the epidemiology and disease course of bullous LP are warranted. There is limited literature evaluating bullous LP separately from other clinical variants of LP, likely due to the rarity of the disease. Although some authors believe that the clinical course of bullous LP is more recalcitrant to standard therapies for lichen planus, there is scant data to support this notion. Areas of future interest include characterization of the epidemiology of bullous LP, features of the clinical course, and the potential role of other therapeutic options that are used for lichen planus, such as phototherapy.

Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Clinical Features

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multi-organ system autoimmune disease that classically presents with cutaneous manifestations such as a malar rash, oral ulcers, discoid lesions, and photosensitivity, seen in up to 76 % of patients during the disease course. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is a rare autoantibody-mediated bullous dermatosis that is seen in 1–5 % of patients with SLE [27–29]. In an epidemiologic study in France, the incidence of bullous SLE was reported to be 0.2 cases per million people, and in a series of 67 patients with subepidermal immunobullous disorders, 3 % had bullous SLE [30]. Patients with SLE can also present with a wide range of antibodies that lead to autoimmune bullous dermatoses such as bullous pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, linear IgA disease, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA). Bullous SLE is a separate autoimmune bullous dermatosis that has been described more recently. It is characterized by a widespread vesiculobullous eruption, with clinical and histological findings resembling bullous pemphigoid or dermatitis herpetiformis. There are at least three different types of bullous SLE based upon the location of the autoantibody in the basement membrane. The most common type of bullous SLE demonstrates antibodies against components of type VII collagen, which can resemble EBA [28].

Clinically, bullous SLE is seen predominantly in African American women in the second and third decades of life. It has only been reported in rare cases in children and adolescents. In relation to SLE, the bullous eruption can occur before the onset of SLE or at any point throughout the disease course; however, patients with bullous SLE tend not to develop other cutaneous manifestations of lupus. Although the onset of bullous SLE eruptions does not necessarily parallel systemic disease activity, there are few reports of bullous flares coinciding with an exacerbation of SLE [31]. The primary lesions are tense vesicles and larger bullae that can be filled with either clear or hemorrhagic fluid and arise in erythematous or normal skin. Multiple vesicles or bullae can form in a cluster, which expand and coalesce to form elongated, arciform, or irregular shapes [30]. Several reports have described erythematous plaques with annular or targetoid erythema multiforme-like configurations. Patients can develop lesions on both sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed skin, but demonstrate a predilection for the flexural and extensor surfaces. Facial and intraoral involvement is relatively common, with common sites including the perioral skin, lip vermillion, oral mucosa, and tongue [32]. Less commonly, the upper trunk and supraclavicular regions are involved [1, 29]. Lesions can be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus or burning sensations. Intraoral lesions initially appear as tense bullae that evolve into painful erosions [33].

On histological examination, the blisters of bullous SLE are subepidermal and contain large numbers of neutrophils and karyorrhectic debris, with occasional lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils (Fig. 11.4). These findings can appear identical to the histology of dermatitis herpetiformis, which is characterized by subepidermal vesicles and papillary-tip neutrophil microabscesses. In biopsies of nonbullous skin, there are neutrophilic microabscesses in the subepidermis, and marked dermal edema with mixed inflammatory cell infiltrates consisting of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes in the upper dermis. On DIF of lesional and perilesional skin, all major classes of immunoglobulins and C3 are often seen in the epidermal basement membrane zone and perivascularly in either granular (60 %) or linear (40 %) patterns [29, 30]. The granular pattern can be differentiated from the pattern seen in dermatitis herpetiformis as the pattern of deposition is not confined to the tips of the dermal papillae as they are in dermatitis herpetiformis. In terms of immunoglobulin deposition, IgG is nearly universally present, observed in up to 100 % of patients, followed by IgA in 67 % and IgM in 50 %, and complement seen in 77 % of cases [1, 28]. Indirect immunofluorescence is negative for anti-BMZ antibodies [34]. Circulating antibodies are also found in bullous SLE, most commonly to type VII collagen in the NC1 domain.

Fig. 11.4

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Subepidermal bulla with neutrophils and karyorrhectic debris. H&E, 10×

The major antigenic epitope in bullous SLE is the fibronectin region of the NC1 domain of type VII collagen, which is also seen in patients with EBA. This region plays an important role in mediating the interaction between anchoring fibrils and other matrix proteins. By anchoring fibrils that cross-link the lamina densa and dermal matrix, this region helps to maintain adhesion at the DEJ. In bullous SLE, the presence of circulating antibodies against this epitope prevents interactions between the collagen and extracellular matrix, which leads to the formation of blisters and complement-mediated damage [29].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree