CHAPTER 20 Pustules, Vesicles, Bullae, and Erosions

Folliculitis

Folliculitis is an extraordinarily common but medically trivial condition.

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Folliculitis is manifested by scattered, red dome-shaped and crusted papules, pustules, or small, round erosions that are left as the pustules quickly rupture (Figures 20.1 and 20.2). Folliculitis occurs primarily on dry, keratinized skin, particularly the proximal, medial thighs due to friction, as well as on the buttocks. Folliculitis produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (hot-tub folliculitis) is manifested by papules that are usually larger and more tender, and pustules are less obvious. These are often prominent in the swimsuit distribution and skin folds.

Figure 20.1 Red papules and pustules on the buttocks are a very common manifestation of folliculitis.

Folliculitis occasionally occurs on the modified mucous membranes, including the labia minora, where lesions often present as small papules with 1–2 mm superficial round erosions (Figure 20.3). Fungal folliculitis of genital skin occurs within plaques of tinea cruris and usually manifests as small nodules or crusts within red, scaling plaques on the proximal, medial thighs (Figure 20.4).

Differential diagnosis

Folliculitis is most often confused with inflamed mollusca contagiosa or insect bites (Figure 20.5). Keratosis pilaris and cutaneous Candida can occasionally mimic folliculitis as well (Table 20.1).

| Diagnosis |

| Clinical appearance |

| Culture for infectious folliculitis |

| Confirmed on biopsy or culture if unresponsive |

| Differential Diagnosis |

| Insect bites |

| Molluscum contagiosum |

| Keratosis pilaris |

| Management |

| Bacterial folliculitis – oral antibiotics according to culture |

| Fungal folliculitis – fluconzaole 200 mg/day, griseofulvin 500 mg bid, itraconazole 200 mg/day |

| Irritant folliculitis – minimize friction, sweat, stop shaving; chronic anti-inflammatory antibiotics (doxycycline or minocycline 100 mg, clindamycin 150 mg bid) |

Management and prognosis

The treatment of folliculitis depends upon the cause. Bacterial folliculitis is treated according to cultures. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, even when community-acquired, is becoming increasingly prevalent, so that cultures are frequently indicated. Pseudomonas folliculitis clears whether or not antibiotic therapy is administered as long as the source of the organism is avoided. Patients with significant pain or constitutional symptoms generally benefit from ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin.

Keratosis pilaris (discussed primarily in Chapter 19)

Keratosis pilaris is a common cause of follicular redness and keratin plugs within follicles. This condition is found most often on the lateral upper arms and the buttocks. The keratin plugs often mimic pustules, but at other times actually produce pustules due to occlusion of the follicle (Figure 20.6). Keratosis pilaris is essentially a normal finding, but patients who do not tolerate the cosmetic aspect are sometimes improved with soaks to soften the keratin plugs and scrubs to remove them. Keratolytics such as lactic acid or salicylic acid have been reported as beneficial, but these are usually too irritating for genital skin.

Mollusca contagiosa (discussed primarily in Chapter 19)

Mollusca contagiosa are virally induced skin lesions that, usually, are manifested by skin-colored, dome-shaped papules. However, trauma or a brisk immune response is associated with red lesions as well as, at times, pustules (see Figure 20.5). The diagnosis is made by the typical appearance of nearby mollusca.

Herpes simplex virus infection

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Genital herpes simplex virus infection occurs most often in younger, sexually active individuals. This is especially common in the adolescent and young adult age group, and it is seen most often in patients who report multiple sexual partners. More people are seropositive for HSV in the United States than Europe, and seropositivity is higher in the western world than in developing countries1. About 17% of people in the United States show exposure to HSV type 2, and about 57.7% to type 12. Clinical disease is present in about 50 million people in the United States3.

Previously, acquisition of HSV infection was believed to occur primarily with sexual activity during an active outbreak. Now, asymptomatic shedding has been identified as a major factor in transmission of HSV infection. Shedding can be detected in asymptomatic women with a history of genital HSV infection on about 5% of days when no lesions are present4. In fact, most infections are transmitted during exposure in the absence of lesions. Clinical manifestations vary, with a primary episode classically appearing quite differently from a recurrent outbreak. First-episode HSV is usually subclinical (or unrecognized), but a true primary first episode typically exhibits widespread vesicles and erosions with only modest grouping of individual lesions (Figures 20.7 and 20.8). These occur on modified mucous membranes of the vulva, on the mucous membranes of the vagina and cervix, and on surrounding dry, keratinized skin. Vaginal and cervical involvement often cause an irritating, purulent vaginal discharge, as well as occasional discharge from the urethra and rectal mucosa. Patients report remarkable pain that sometimes prevents micturition, and swelling is often substantial. Bilateral lymphadenopathy is common, and some patients exhibit fever, myalgias, and headache. A primary outbreak generally requires about 2 weeks for complete evolution of blistering, crusting, and healing.

Most patients experience recurrences within the first year, which can be mild and occasional, or as often as two or three episodes per month. The frequency and severity of recurrences are less with infection produced by HSV type 1 than by type 25,6. With the progression of time, episodes usually become less frequent, less severe, and less painful. Most often, the first recognized episode is a recurrence following a subclinical primary infection.

Recurrent HSV infection is usually manifested by a prodrome of tingling, itching, or burning. This is quickly followed by red vesicopapules which progress into one or several plaques of clustered vesicles which erode into coalescing erosions (Figures 20.9 and 20.10). Often, this is one small plaque. In addition to blisters and round erosions, fissures can occur as a result of an HSV recurrence. Immunosuppressed women sometimes develop typical, ulcerative, chronic HSV infection.

Differential diagnosis

Other causes of superficial, small, coalescing red papules and erosions include candidiasis, bullous impetigo, folliculitis, mollusca contagiosa, and very small aphthae (Table 20.2). A fixed drug eruption causes recurrent same-site erosions, although individual erosions are generally significantly larger than the small coalescing erosions of HSV infection. HSV can be differentiated by cultures, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, or by biopsy. Positive serological tests only report previous exposure, not necessarily current infection.

Table 20.2 Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

| Diagnosis |

| Clinical appearance |

| Positive culture or polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus (HSV) |

| Biopsy |

| Differential Diagnosis for Primary HSV |

| Candidiasis |

| Molluscum contagiosum |

| Bullous impetigo |

| Blistering/erosive contact dermatitis |

| Differential Diagnosis for Recurrent HSV |

| Fixed drug eruption |

| Herpes zoster |

| Blistering/erosive contact dermatitis |

| Management |

| Patient education and counseling |

| Oral antiviral medication for primary episode within the first 3 days |

| Oral antiviral medication at onset of prodrome for recurrent outbreaks or daily suppression |

Laboratory and histology

A biopsy is an excellent means of nearly definitive, rapid diagnosis. Histology reveals ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes, where individual epidermal cells coalesce into very large multinucleated cells. This finding is only seen with the herpetic blisters of HSV, varicella, or herpes zoster.

Therapy and prognosis

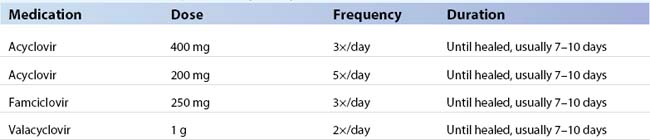

HSV infection cannot be cured, but it can be controlled very well, and outbreaks can be nearly eliminated with ongoing suppressive oral antiviral therapy. Topical therapy generally produces statistically but not clinically significant amelioration of disease. First-episode, primary HSV infection is best treated with any of several oral antiviral therapies (Table 20.3).

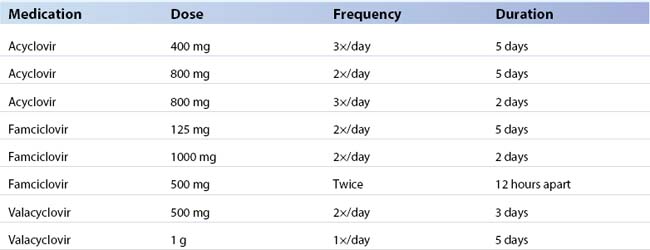

Recurrent HSV infection can be managed several ways, again orally (Table 20.4). First, if patients experience mild or only occasional recurrences, the individual may choose no treatment. Otherwise, patients can take an oral antiviral medication immediately with the onset of the prodrome, often preventing the outbreak. Patients with frequently recurrent outbreaks, those with recurrences not prevented by immediate therapy, and those with a psychological need to eliminate as many symptoms as possible benefit from daily suppression (Table 20.5). Immunosuppressed patients often require daily suppression to prevent either very frequent outbreaks or chronic HSV erosions and ulcers (Figure 20.11). Unfortunately, immunosuppressed patients have a slight risk for resistant HSV infection that is uncontrolled with currently available antiviral therapies. Foscarnet is sometimes useful in that event. The advent of effective therapy for the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome has significantly decreased the frequency of resistant HSV infection.

Table 20.5 Schedules for Suppression of Genital Herpes Simplex Virus Infection3

| Medication | Dose | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Acyclovir | 400 mg | 2×/day |

| Famciclovir | 250 mg | 2×/day |

| Valacyclovir | 500 mg | 1×/day |

| Valacyclovir | 1 g | 1×/day |

Reasons for treating and suppressing HSV, in addition to personal patient comfort, include decreasing the risk of transmission of the disease. The risk of transmission of infection to a regular partner has been estimated to be about 10% per year when couples only avoid sexual activity during a clinical outbreak7. Interestingly, this study showed that all seroconversions occurred in the female partner, suggesting that women are at higher risk than men. The addition of barrier protection and suppressive antiviral medication reduces but does not eliminate this risk. In one study, daily valacyclovir and famciclovir decreased shedding to 1.3% and 3.2% of days, respectively, with historical shedding rates at about 5%8.

Women should be made aware that a very unlikely but important primary morbidity of HSV infection is perinatal transmission to a newborn. The majority of neonatal herpes occurs in the presence of a new primary first-episode HSV infection, rather than from a mother with known HSV who has a clinical recurrence at delivery. In addition, the sequelae for the infant are less severe for those with type 1 HSV than type 2. Although the risk of a transmission to a neonate is small, this is a disease with tragic consequences, and the mother and her obstetrician should be aware.

Varicella-zoster virus infection; varicella (chickenpox), herpes zoster virus infection (shingles)

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations

Varicella is a classic childhood viral infection that occurs in nonimmunized individuals. Fortunately, since the relatively recent availability of the varicella vaccine, varicella has become uncommon. Herpes zoster occurs most often in older people as their immune system begins to wane, and the virus migrates from the ganglion, where it has lain dormant, to the skin, producing classic shingles. This occurs earlier in patients who are immunosuppressed for reasons other than age. Although a vaccine is now available for the prevention of herpes zoster, it is not yet widely used9.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree