Type I

Isolated ligamentous injury of the posterolateral corner (PLC), including the FCL, popliteus, or popliteofibular ligament injury

Type IIa

Combined ligamentous injury of the PLC, including injury to the distal FCL and biceps femoris, with either avulsion or fracture of the fibular head

Type IIb

Combined ligamentous injury of the PLC, including injury to the FCL and popliteus, occurring at the proximal femoral region

Type IIIa

PLC knee injury with some combination of FCL (proximal, distal, or midsubstance), popliteus (proximal, midsubstance, or musculotendinous), biceps femoris (distal, musculotendinous), posterolateral capsule, IT band

Type IIIb

PLC knee injury, Type IIIa with uni-cruciate or bi-cruciate injury

Treatment

If an acute injury occurs in the setting of a failed ACL reconstruction, numerous options are available. If there are distal avulsions of the FCL/biceps femoris complex, then acute repair may be indicated, especially in the setting of bony avulsions or complete distal avulsions off of the fibula. However, Stannard et al. and Levy et al. have both shown higher failure rates with repair as opposed to reconstruction in the setting of acute FCL/PLC injury [11, 12]. In the setting of a revision ACL procedure combined with a PLC reconstruction, we prefer an anatomic reconstruction technique.

LaPrade et al. described the “true anatomic” technique [13]. Biomechanical testing on cadavers in the laboratory was translated into a clinical series that evaluated outcome. This technique reconstructs the FCL, the PFL, and the popliteus tendon complex with tunnels at each anatomic origin and insertion site. The authors reported on 46 patients with combined PLC and cruciate ligament injuries with a mean follow-up of 4.3 years. They found significant improvements in IKDC scores for varus stress testing, external rotation at 30°, and the reverse pivot shift as well as improved performance of the single-leg hop test [12]. However, this technique is technically challenging and requires a more extensive exposure and the creation of additional tunnels.

Our preference is an anatomic reconstructive technique (Fig. 20.1) that is less complex than some other anatomic techniques and does not require the creation of a tibial tunnel, which is particularly advantageous in the setting of a revision ACL reconstructive procedure [14]. However, if the patient has asymmetric hyperextension, then we may elect to add a popliteal-based graft similar to that described by Laprade et al., [13] and Fanelli et al. [15].

Fig. 20.1

(a) Tunnel placement and graft construct. (b) Graft construct, followed by posterolateral capsular shift. Reproduced from Schechinger SJ, Levy BA, Dajani KA, Shah JP, Herrera DA, Marx RG. Achilles tendon allograft reconstruction of the fibular collateral ligament and posterolateral corner. Arthroscopy 2009;25:3;232–42, with permission from Elsevier

For our standard technique, we fix the ACL revision graft on the femur. Definitive fixation of the ACL on the tibia is deferred at this point. The incision is carried out over the lateral epicondyle extending toward the anterior border of the fibula. Anterior and posterior full-thickness flaps are raised to expose the iliotibial band and the biceps femoris muscle complex. The peroneal nerve is identified posterior to the biceps femoris and followed proximally and distally to ensure that it is not tethered through its course and enabling its protection throughout the procedure with the aid of a vessel loop. The iliotibial band is then incised in line with the skin incision. The anterior and posterior borders of the fibula are identified, and subperiosteal dissection is performed, by use of a Bovey and small Cobb. After exposure of the fibular head, access to the anterior sulcus of the popliteus and insertion of the FCL is created with dissection over the lateral aspect of the femur. A tract is developed from the posterior border of the fibula, underneath the biceps femoris, and toward the popliteus sulcus for later passage of the graft. Under fluoroscopic control, a K-wire is passed through the anterior one-fifth of the popliteal sulcus and then over-reamed with a 9-mm reamer to a depth of 20 mm (Fig. 20.2). A nonirradiated fresh-frozen Achilles tendon allograft with a 9 × 20-mm bone plug on one end and 7-mm graft along its tendinous portion is prepared (Fig. 20.3). One of us [MC] does not have access to allograft tissue, so hamstring autograft is used instead. The bone plug of the allograft is then placed into the tunnel created at the popliteus sulcus and secured with an 8 × 20-mm interference screw allowing for bone–bone fixation (Fig. 20.4). After securing the graft, the fibular tunnel is then prepared. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a K-wire is passed from the anterolateral fibula at the attachment site of the FCL to the posteromedial down-slope of the fibular styloid, where the PFL attaches to the posterior border of the fibula (Fig. 20.4). Once in the appropriate position, the K-wire is then over-reamed with a 7-mm reamer. The graft is passed underneath the biceps femoris through the tract that was previously developed, and a suture passer is passed anterior to posterior through the 7-mm hole in the fibula. At this point, the graft is passed posterior to anterior through the fibula, recreating the popliteal fibular ligament. The graft is then looped back over to the lateral epicondyle at the insertion of the FCL, approximately 18.5 mm proximal and posterior to the popliteus tendon insertion, to re-create the FCL. Once again, under fluoroscopic control, a Beath pin is passed at the FCL insertion to ensure that its path is not intruding on other reconstructed ligament tunnels (Fig. 20.5). With the Beath pin in place, the graft is checked for isometry in flexion and extension (Fig. 20.6).

Fig. 20.2

Fluoroscopic anteroposterior view of K-wire position for femoral tunnel in popliteal sulcus. Reproduced from Schechinger SJ, Levy BA, Dajani KA, Shah JP, Herrera DA, Marx RG. Achilles tendon allograft reconstruction of the fibular collateral ligament and posterolateral corner. Arthroscopy 2009;25:3;232–42, with permission from Elsevier

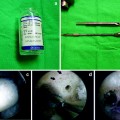

Fig. 20.3

Achilles tendon allograft with 9 × 20-mm bone plug and 7-mm graft. Reproduced from Schechinger SJ, Levy BA, Dajani KA, Shah JP, Herrera DA, Marx RG. Achilles tendon allograft reconstruction of the fibular collateral ligament and posterolateral corner. Arthroscopy 2009;25:3;232–42, with permission from Elsevier

Fig. 20.4

Fluoroscopic anteroposterior view of bone block secured with metal interference screw at popliteal sulcus and K-wire placement for fibular tunnel. Reproduced from Schechinger SJ, Levy BA, Dajani KA, Shah JP, Herrera DA, Marx RG. Achilles tendon allograft reconstruction of the fibular collateral ligament and posterolateral corner. Arthroscopy 2009;25:3;232–42, with permission from Elsevier