CHAPTER 14 Posterior and Posteroinferior Approaches

KEY POINTS

Short external rotators and trochanteric bursa should be repaired with care; the repair is tested with hip flexion before closure of the fascia.

Short external rotators and trochanteric bursa should be repaired with care; the repair is tested with hip flexion before closure of the fascia.The posterior or Moore Southern approach is the most popular technique for total hip arthroplasty. It has some marked advantages over other approaches to the hip. Less extensive tissue dissection is needed with this approach than with others, and this approach does not violate the abductor mechanism. Therefore, patients have a lower incidence of postoperative Trendelenburg gait. The exposure also provides good access to the acetabulum and the femur and can be extended either proximally to address pelvic dissociation with plating of the posterior column, or distally to address femoral fracture. The posterior approach is associated with a lower incidence of heterotopic bone formation. It has a historically higher dislocation rate compared with the anterolateral approach, but this is not the case when an enhanced posterior repair is used.1

After trying for seven years to reduce the problems encountered with hip resurfacing, we advocate the posteroinferior approach. The approach has all the benefits of our standard posterior approach: it preserves all cutaneous nerves by passing between the known angiodermatomes2; preserves the iliotibial band and the trochanteric bursa; and avoids any dissection of the gluteus medius and minimus, which improves abductor function and reduces the risk of heterotopic bone formation.

POSTERIOR APPROACH

Patient Positioning

A pillow is placed between the legs to prevent excessive adduction, and the hip is placed in 45 degrees of flexion with the knee flexed to 90 degrees. (We try to keep the knee flexed when possible during the procedure to minimize tension on the sciatic nerve.) The tip of the greater trochanter is then marked (Fig. 14-1).

FIGURE 14-1 The tip of the greater trochanter is marked first, followed by the incision site.

(Courtesy of Charles Frewen, Director Medical Visuals Pty, Ltd.)

The skin incision runs parallel to the posterior border of the femur and curves posteriorly at the tip of the greater trochanter to run parallel to the fibers of the gluteus maximus. As a rule of thumb, about one third of the incision should usually be proximal to the tip of the greater trochanter, although this depends on the femoral anatomy, as already discussed. The length of the incision on a slim patient with moderate muscle mass and a flexible hip can be routinely less than 10 cm with practice.3

External Rotators

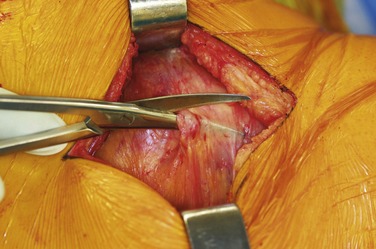

The posterior fat tissue and bursa are divided with scissors, taking care to leave a layer of tissue that can be closed over the short external rotators (Fig. 14-2). The hip is now brought into internal rotation by resting the foot on a well-padded Mayo table. Scissors are used to define the posterior border of the gluteus medius, where a Deaver or Langenbeck retractor is inserted (Fig. 14-3). The retractor exposes the piriformis muscle that can be confirmed by palpation, because it is a characteristic cylindrical tendon.

FIGURE 14-2 The bursa is cut with scissors to allow repair.

(Courtesy of Charles Frewen, Director Medical Visuals Pty, Ltd.)

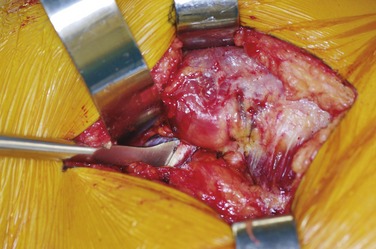

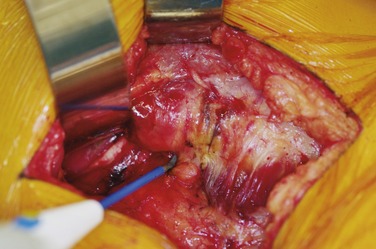

The junction of the gluteus minimus and piriformis is defined with diathermy. A Cobb retractor is passed between the short external rotators and the capsule, as well as between the gluteus minimus and the capsule, to define the plane for dissection (Fig. 14-4). The hip is held in extension and less internal rotation while this is done to prevent damage to the muscles through excessive stretching. The hip is now placed in internal rotation so that the piriformis and conjoined tendon (obturator internus and gemelli) can be divided. A long diathermy is bent to allow the tendons to be cut at their insertions (Fig. 14-5). Near the insertion, the piriformis tendon forms a crescent shaped cross-section that grips the circular conjoined tendon. If two cylindrical tendons are released, it is likely that they have been divided far from their insertion.

FIGURE 14-4 Cobb retractor used to define the plane between the external rotators and the capsule.

(Courtesy of Charles Frewen, Director Medical Visuals Pty, Ltd.)

FIGURE 14-5 External rotators are cut with a long diathermy starting distal to the tendon insertion.

(Courtesy of Charles Frewen, Director Medical Visuals Pty, Ltd.)

Two Kessler sutures are placed in the external rotator tendons,4 clips are placed on them, and they are retracted posteriorly to protect the sciatic nerve. We recommend 2 Vicryl or 2 Polysorb sutures, because they are strong but will not linger and potentially irritate the bursa.