CHAPTER 6 Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy

Introduction

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), is one of the most common gestational dermatoses, affecting about one in 160 pregnancies. It is essentially a self-limiting, papular, urticarial eruption of late pregnancy and/or the puerperium. Polymorphous features may be present and include vesicles, target lesions, polycyclic wheals, a widespread toxic erythema-like appearance, and eczematous changes.

Historical background

As PEP has a very variable clinical morphology1, it is not surprising that various terms have been used to describe it. The disease was initially reported as “toxemic rash of pregnancy”2, but as the case was not associated with pre-eclampsia, the term was little used. Since then other descriptive terms have been used, including “prurigo of late pregnancy”3, “toxic erythema of pregnancy”4, and “PUPPP”5,6.

Although the term “PUPPP” is still widely used, particularly in the United States, it is generally agreed that PUPPP and PEP are identical dermatoses7. This discussion will refer to PEP, because it encapsulates the full range of clinical morphologic expressions, including papules, plaques, target lesions, polycyclic erythematous wheals, vesicles, with occasional small bullae, and eczematous changes.

Etiology

PEP is an inflammatory dermatosis associated solely with pregnancy. No associations have been found with atopy, pre-eclampsia, or autoimmune phenomena1, and the frequency of human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) in women with PEP is also normal1,6. The striking association of PEP with abdominal striae observed mainly in the late pregnancy of primigravidae has favored rapid, late abdominal wall distension with consecutive damage to connective tissue as an important aspect in the development of PEP. A reaction to abdominal distension has also been implicated by the greater likelihood in PEP of higher maternal weight gain8 and an increased incidence of twins9,10 or multiple pregnancies8,11,12. Associations with higher neonatal birth weight or particular fetal sex, however, have not been confirmed, but a more recent study suggests a higher incidence of male fetuses and cesarian deliveries8,12. A prospective study of 44 patients with PEP showed low serum cortisol levels compared with controls, suggesting a hormonal influence11, although the relevance of this is currently not clear. No evidence has been found to implicate autoimmune mechanisms11–14, nor have circulating immune complexes been found6. A preliminary study of male DNA detection in PEP indicated that fetal cells can migrate to maternal skin during pregnancy15. Whether this initiates the inflammatory responses in PEP remains speculative as these findings have not been substantiated by others. Although PEP is now a well-recognized entity, it is perhaps surprising that there is little substantial information about its etiology, and factors such as parity, multiple pregnancy, and paternity may well need further consideration16.

Clinical features

The great majority of patients with PEP are primigravidae, and the development of PEP in a subsequent pregnancy is very likely to coexist with excessive maternal weight gain or multiple pregnancies11,16,17. The characteristic time of onset is between weeks 36 and 39 of gestation, but lesions may also develop in the immediate postpartum period (15%)8 or occasionally in the late second trimester. There is no particular maternal age at which PEP is likely to develop6.

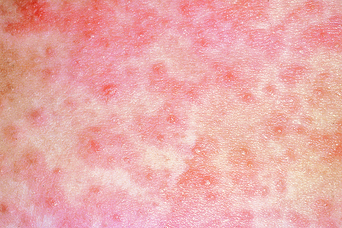

The mean duration of the eruption is 6 weeks, but the eruption is usually not severe for more than 1 week1. The eruption begins with pruritic urticarial papules, usually in association with striae distensae (Figures 6.1–6.4); however, these papules can rarely develop on the abdomen without striae (Figure 6.5). Earlier reports of PEP indicated that the lesions consisted almost exclusively of urticarial papules and plaques5. However, the morphology of the eruption may vary greatly throughout its duration1,11 and exhibits a characteristic change with disease progression8. While pruritic urticarial papules and plaques are the main morphological features at disease onset (98%), more than one-half of the patients (51%) develop polymorphous features later on8. These include tiny vesicles, in 17–40% of patients (Figure 6.6), often on top of the papules overlying striae (Figure 6.7). In a small number of cases, these vesicles may coalesce to form smaller bullae18. Target-like lesions and annular or polycyclic wheals are present in 6–20% of cases (Figure 6.8). In 70% the lesions become confluent and widespread, resembling a toxic erythema (Figure 6.9). The Koebner or isomorphic response in PEP is common1, but facial involvement is very rare19,20. As the eruption slowly resolves, the great majority of cases exhibit fine scaling and crusting, reminiscent of eczema1,8.

Figure 6.3 Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy in striae distensae. Close-up of Figure 6.2, showing confluent urticarial papules in striae distensae. Some papules occur adjacent to the striae.